|

Another contemporary review of Henry Reed's A Map of Verona has turned up, this time in the New Review for June, 1946. F.J. Friend-Pereira (1907–1957) reviews "Four Poets" in the Some Recent Books column, including The Sand Castle by C.C. Abbott, A Map of Verona, Poems by Jonathan Wilson, and Theseus and the Minotaur by Patric Dickinson.

Jonathan Wilson died during the Second World War, in Holland 1944. His work seems well-received here, but I can find little else about him. Friend-Pereira is lukewarm about Reed's collection, but has a few nice things to say about the Tintagel sequence. Worth adding to the "blurbs" page for shorter reviews of Reed's work. A Map of Verona is more pretentious: Mr. Reed, when he wrote his poems 'used to like ambiguity'. There is some of the expected depth and subtlety in several of the pieces; but much of the writing appears needlessly prosaic and splay-footed. Mr. Reed has submitted to various up-to-the-minute influences: Eliot, Auden, Macneice, Day Lewis: and it comes as a surprise to see that in one poem he echoes someone so poetically different from these as William Morris! Felicitous phrases like 'a shining smile of snowfall, late in Spring', are mixed, up with fashionable (so-called Eliot-esque) lack of interest: 'The place not worth describing, but like every empty place'. The best poems are the four included under the general title of 'Tintagel'. Here Mr. Reed shows a keen eye, a ready pen, and a pleasing sense of the dramatic: the Arthurian theme does not, in his hands, seem vieux jeu.

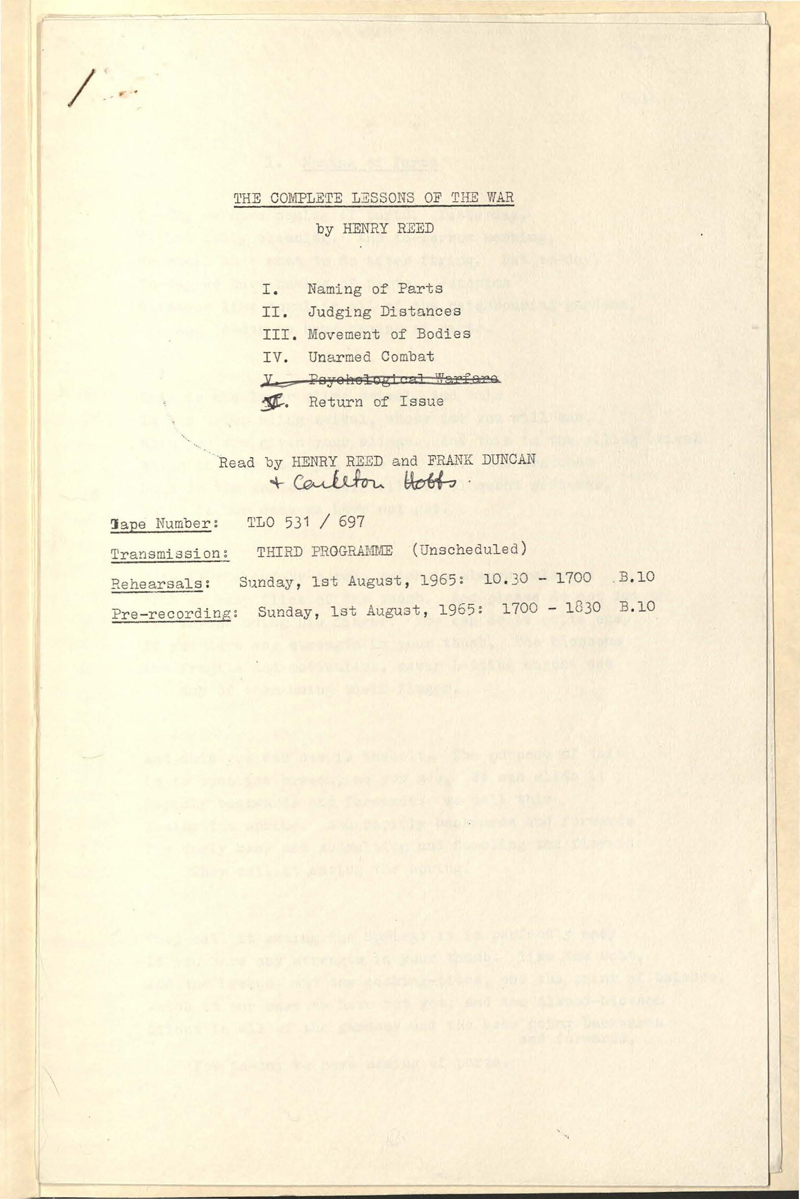

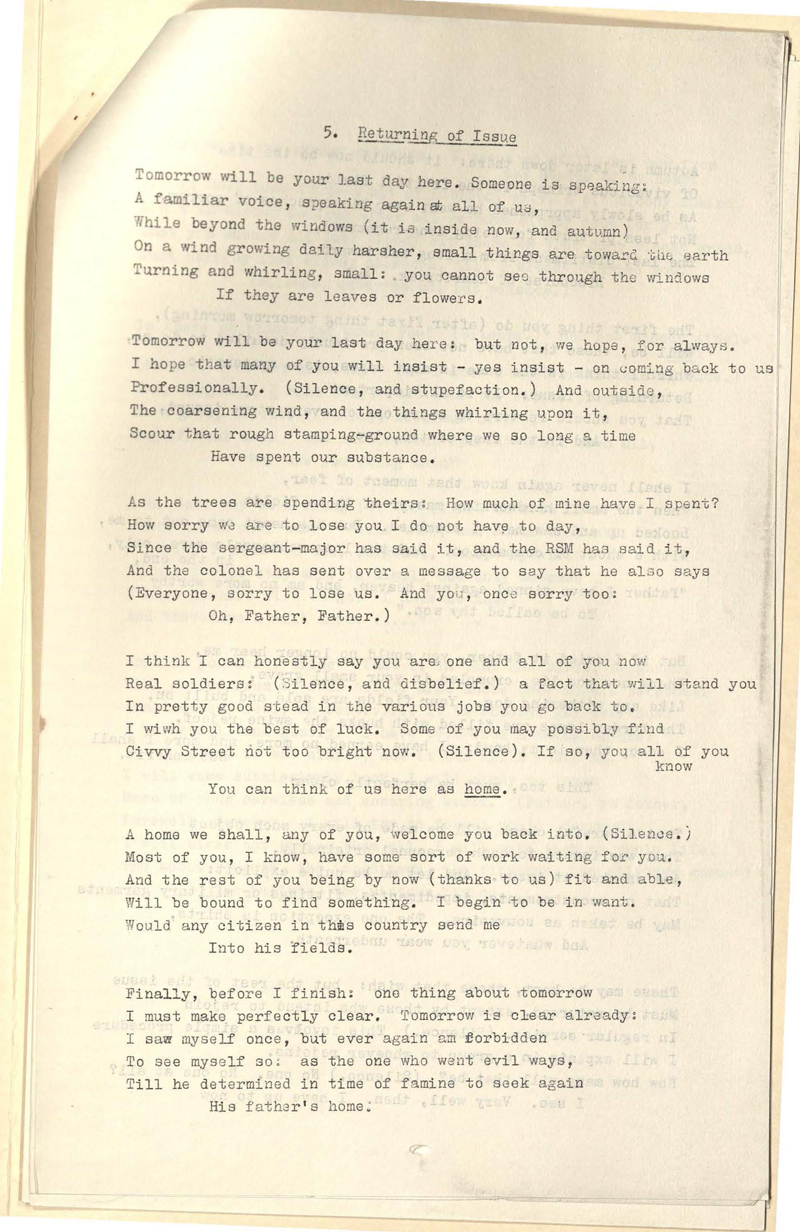

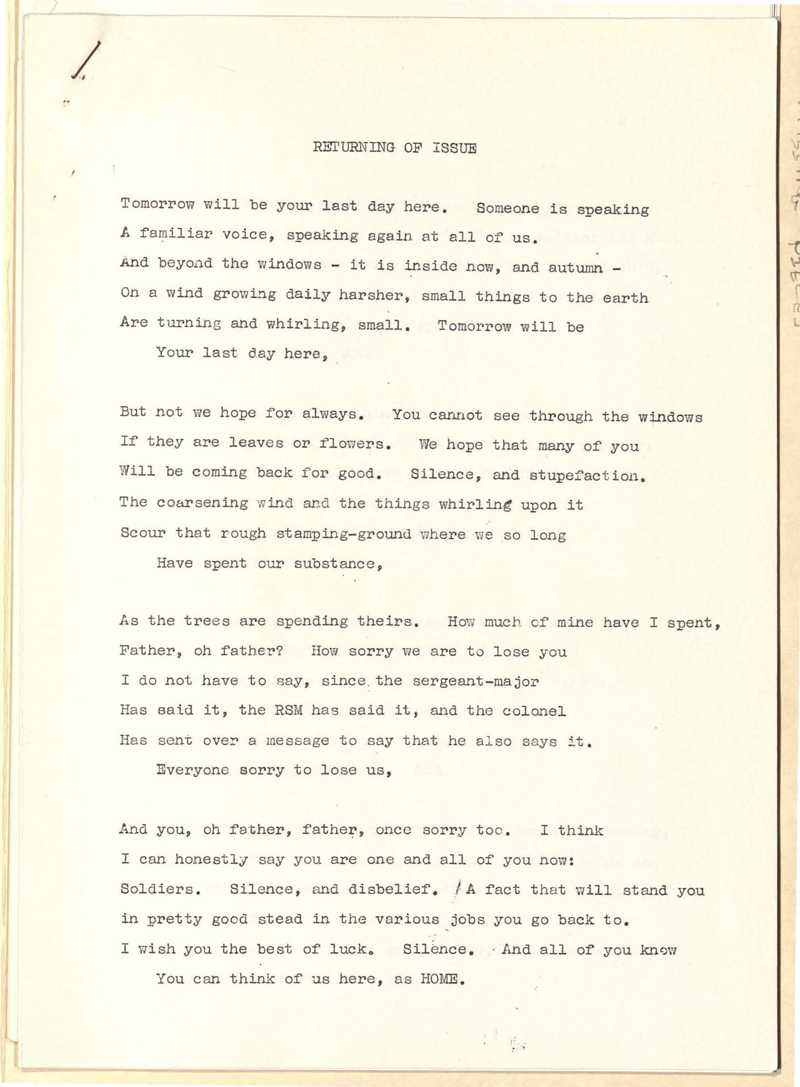

Here is a unique opportunity to see Henry Reed's editing process, over the span of five years' time. Below are shown two scripts for the BBC broadcasts of Reed's The Complete Lessons of the War, the first from February, 1966, and the second from a later broadcast, in December 1970. The 1970 program was in conjunction with the collection Lessons of the War, published by Reed's producer, Douglas Cleverdon and his press, Clover Hill Editions.

On the front page of the script from 1965, you can see that — in addition to the five Lessons of the War poems read on the air on Radio 3 — the poem "Psychological Warfare" was also scheduled, but ultimately crossed out. Reed was obviously unhappy with it, and it was still unfinished before 1970. "Psychological Warfare" was not published until Reed's Collected Poems appeared in 1991 (edited by Jon Stallworthy), and actually made its debut in March of that year, in the London Review of Books. The scripts for the other Lessons of the War poems, "Naming of Parts," "Judging Distances," "Unarmed Combat," and "Movement of Bodies," are all the same. But Reed continued to revise "Returning of Issue" — which he always kept last as the coda to the Lessons of the War sequence — until the poems were published in collection. The billing for 1970's Complete Lessons of the War states that "The fifth poem, Returning of Issue, has been largely rewritten since the programme was first broadcast in 1966. This new version has been re-recorded." Notice the text cut between the two, the dispensable adjectives lost, and the line breaks shifted: In the 1965 script for broadcast, the first two stanzas are (and in direct contrast to the season of spring from "Naming of Parts" in 1946): Tomorrow will be your last day here. Someone is speaking:While in the 1970 script, rewritten and re-recorded for the new broadcast, we find the whole poem much improved, and restructured to conform more with the other early Lessons poems. The revised stanzas are as follows: Tomorrow will be your last day here. Someone is speakingYou can view scans of the full scripts, here: both from 1965, but one without a revised "Returning of Issue," and the other with several revised copies of the poem, circa 1970.

Here is a terrific find. I wish I could reproduce the exact combination of keywords which led me to this review in Google Books, but I can't. I was lamenting the apparent loss of the ability in Books' tools to be able to sort by date (instead of keyword relevance), and trying various combinations of "map of verona" and limiting "Any time" to a custom range of years, like 1946-1949.

Up pops this snippet from a post-war volume of the Mercure de France:  I was incredulous. It's obviously a contemporary book review of Reed's book of poetry, A Map of Verona (1946). But where was I going to find a library with a run of a French periodical? Leave it to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. They've digitized Mercure de France from 1890-1954. I was a bit confused by the lack of issues from 1941-1946, but I realized if they weren't publishing during World War II, then the review must be in a later issue. I didn't have to search long. Searches in Gallica for "Henry Reed" were coming up empty, but I could see another review on the same page in the Google Books search. A search for "John Pudney" led me straight to the issue for "1er janvier 1947." Here, under the section for "Grand-Bretagne" written by Jacques Vallette, is an entire article devoted to Aldous Huxley, and reviews of English language books. The books reviewed are:

So, there: I finally have a non-English language book review for The Poetry of Reed site: "Henry Reed in the Mercure de France."

Robert Robinson (1927–2011), famed of television and radio, was an acquaintance and huge fan of Henry Reed. I mostly know of Robinson through Stephen Fry's frequent impressions of him: "Ah, would that it were, would that it were." (Here are Fry and Laurie simultaneously imitating Robinson.)

In Robinson's memoir, Skip All That (1996), he professes his admiration for Reed's 1953 BBC radio comedy, A Very Great Man Indeed: It is, Robinson says, "the one wholly original contribution made by radio to the canon of English humorous letters." Members of the same club in London, The Savile, Robinson reveals that, after getting to know each other, Reed presented him with a scrap of verse, now (along with some personal correspondence from Ezra Pound) among his prized possessions:  A Very Great Man Indeed was a fiction that accumulated round the figure of an innocent middle-aged literary gent who was trying to write the biography of a great writer. It was a Third Programme programme 'the ever-admirable Third Programme' as Michael Flanders, playing the part of a BBC commentator in the series, described it — and was transmitted in fifty-minute episodes. So intense were its comic flavours, so distinct were its characters, so remarkable was the understanding of the actors for the parts they played, that I became addicted. Henry Reed was the author, whose poem 'Today We Have Naming of Parts' and whose lampoon of the Eliot Quartets, 'Chard Whitlow', are imperishable items in the repertoire of post-war anthologies.Here is an obituary and remembrance of Robinson, from 2011.

At long last — and long sought-after — David Lodge's 1983 documentary on Birmingham writers in the 1930s, "As I Was Walking Down Bristol Street," is available online, in its entirety. Lodge, an author and critic, was Professor of English Literature at the University of Birmingham from 1976 until 1987.

The film gives a short history of the authors who made up the Birmingham Group, primarily Walter Allen, Walter Brierley, Leslie Halward, John Hampson, Reggie Smith, and by association, Louis MacNeice and W.H. Auden. Allen and Smith, both old school chums of Henry Reed from Edward VI Grammar School, Aston (and later at university) give interviews for the film. A highlight is the story how of Auden would introduce his heterosexual friend: "This is Reggie Smith. He's not one of us, my dear, but we have hopes for him." Henry Reed is mentioned by Smith at around the 23-minute mark, in a famous anecdote regarding Louis MacNeice's farewell party, when he was leaving Birmingham University for Bedford College, in 1936. Smith recalls: "That was where Henry Reed nearly had his arse burnt off because somebody — well it wasn't somebody, it was the director from the Group Theater [Rupert Doone] — who got himself into a great state of anguish because he'd just done — he was talking to professor Dodds, this big man was explaining to him that he always saw it as a "fountain of blood, you see an idea: I see it as a fountain of blood" [for a production of MacNeice's Agamemnon] and Dodds said 'you'd find that a bit difficult perhaps to put on the stage' and he got very hurt at that suggestion and said 'I don't care' and threw his vodka into the fire which leapt out, like a flame, and burnt the backside of Henry Reed, who was minding his own business at the fireside. But it's a party that went on for days and days." The film has Lodge in MacNeice's former flat above the coach house at Highfield, Selly Park, where the legendary party took place.

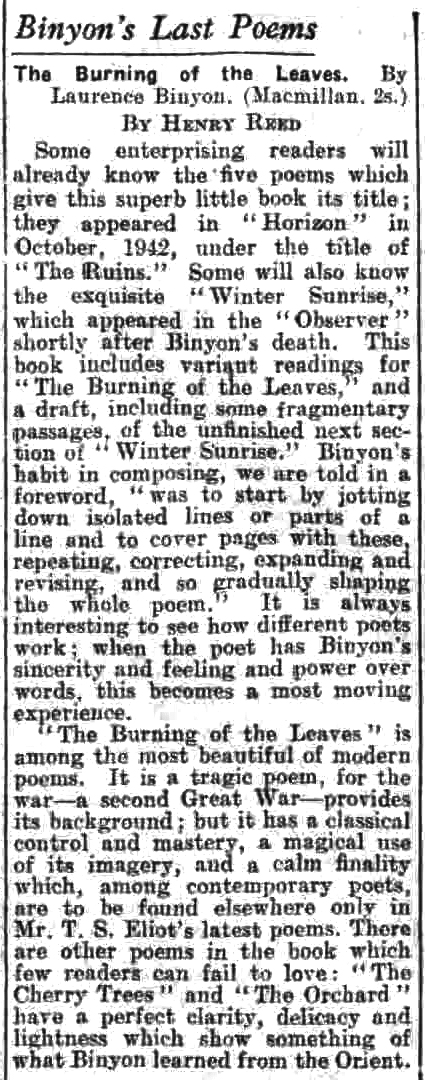

Re-entering the time machine that is the British Newspaper Archive, I have turned up another couple of early book reviews by Henry Reed, in his hometown Birmingham Post during 1944 and 1945. Here, Reed reviews the posthumously published "last" poems by Laurence Binyon (December 27, 1944, p. 2), including the titular "The Burning of the Leaves," written during the London Blitz:

"They will come again, the leaf and the flower, to ariseInterestingly here, Reed refers to the ongoing war as "a second Great War": a war he was still enduring in 1944, working in the Japanese section of Bletchley Park.   Binyon's Last Poems

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||