|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Biography"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

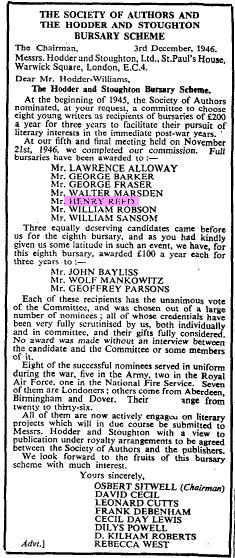

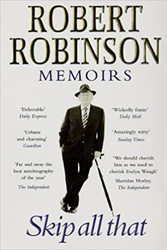

Robert Robinson (1927–2011), famed of television and radio, was an acquaintance and huge fan of Henry Reed. I mostly know of Robinson through Stephen Fry's frequent impressions of him: "Ah, would that it were, would that it were." (Here are Fry and Laurie simultaneously imitating Robinson.)

In Robinson's memoir, Skip All That (1996), he professes his admiration for Reed's 1953 BBC radio comedy, A Very Great Man Indeed: It is, Robinson says, "the one wholly original contribution made by radio to the canon of English humorous letters."

Members of the same club in London, The Savile, Robinson reveals that, after getting to know each other, Reed presented him with a scrap of verse, now (along with some personal correspondence from Ezra Pound) among his prized possessions:

A Very Great Man Indeed was a fiction that accumulated round the figure of an innocent middle-aged literary gent who was trying to write the biography of a great writer. It was a Third Programme programme 'the ever-admirable Third Programme' as Michael Flanders, playing the part of a BBC commentator in the series, described it — and was transmitted in fifty-minute episodes. So intense were its comic flavours, so distinct were its characters, so remarkable was the understanding of the actors for the parts they played, that I became addicted. Henry Reed was the author, whose poem 'Today We Have Naming of Parts' and whose lampoon of the Eliot Quartets, 'Chard Whitlow', are imperishable items in the repertoire of post-war anthologies.

The narratives grew out of Reed's chronic failure to get to grips with a long projected life of Thomas Hardy. The hapless biographer in A Very Great Man is called Herbert Reeve, though the people he meets in the course of his researches very often get this wrong and call him Reeves, Treves or even Breve. As in Toytown the characters are amiable, grotesque, recognisable, the two principal figures being General Gland, the foot fetishist and bell fancier, who in moments of stress pronounces 'd' as 'b' (e.g. 'Breadful!') and the composeress Hilda Tablet whose 'musique concrete renforcee' is the talk of the avant-garde. The General's portrait, painted in the nude by R. Bunnington Benningfield ARA hangs in his hall. 'Breadfully realistic, isn't it?' asks the General glumly, as he shows it to Reeve, 'apart from being fourteen feet high, of course.' Hilda's nine-act opera Emily Butter is set in a department store and on the first night at Covent Garden the curtain finally comes down in the small hours of the morning.

Reed made these figures, and many others, sound like your own relatives, a gift he shared with S.G. Hulme Beaman, creator of Toytown, and with the great Beachcomber, and with Lewis Carroll. Reed was a melancholy recluse, and I would meet him from time to time at the Savile Club where he would listen to my enthusiastic prattle about a work which I still feel is the one wholly original contribution made by radio to the canon of English humorous letters. Reed was pleased enough with this succès d'estime and knew how much he owed to the craft of Douglas Cleverdon who was the producer, and to the sensitivity of such actors as Derek Guyler (creator of General Gland, and also of a minor character, Mr Gabriel Hall Pollock, the music critic, whose glottal pronunciation of the word 'beauty' was much prized), Mary O'Farrell (Hilda) and Hugh Burden (Herbert Reeve). But this saturnine figure was never cheerful, and as men left the Club to catch their last train, he would wander off to his bachelor apartment in Montagu Street, expecting (I always thought) the worst. One night before he left he wrote out a verse for me a verse he had dreamt:

Whenever Waterson saw something of interest or note,

He sate down at once about it, and to his grandmother wrote:

'You should have seen this thing, it is the kind of thing I like.

I saw it today, from my bike.' The two Pound letters, and the verse that Henry Reed dreamt, are true relics to me. And like true relics, cannot be reduced or explained. Here is an obituary and remembrance of Robinson, from 2011.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

From the Collection of Thomas Hardy Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto:

Max Gate, Dorchester, 6 May 1936

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed, poet, dramatist, and would-be Hardy biographer concerning Hardy's poem 'Looking Back' and Reed's prospective visit.1

Max Gate, Dorchester, 9 Aug. 1936

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed expressing her pleasure at seeing him and helping his research.

Max Gate, Dorchester, 25 Dec. [1936]

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed discouraging him with regards to any projected biography of Hardy and the possible performance of The Dynasts.

Max Gate, Dorchester, 21 Apr. 1937

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed concerning her illness and the desirability of his delaying the proposed biography of her husband.

1 "Looking Back" was first published in Richard L. Purdy's Thomas Hardy: A Bibliographic Study (London: Oxford University Press, 1954), p. 149.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

Henry Reed was, for a short time in the 1930s and 40s, the consummate Hardy scholar. Reed wrote his master's thesis at the University of Birmingham on " The Early Life and Works of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1878." He visited Florence Emily Hardy in 1936 as part of his research, and sat in Hardy's study at Max Gate transcribing letters.

Reed's ambition was to write the life of Thomas Hardy. He was thwarted by his own perfectionism, and — according to this 1962 review from the Sunday Telegraph of the republication in one volume of Florence Hardy's Life of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1928 — by Thomas Hardy, himself. The official biography which was published in 1928 and 1930 was nothing less than Hardy's own autobiography.

Reed's scholarly adventures eventually provided the fodder for his sequence of Hilda Tablet radio plays featuring the late "poet's novelist," Richard Shewin, as a stand-in for Hardy.

Reed's frustration with trying to write his own life of Hardy is scarcely disguised in his book review, but it can also be heard the most perfect parody of Hardy's poetry, " Stoutheart on the Southern Railway," written by Reed sometime in the 1950s:

What are you doing, oh high-souled lad,

Writing a book about me?

And peering so closely at good and bad,

That one thing you do not see:

A shadow which falls on your writing-pad;

It is not of a sort to make men glad.

It were better should such unbe. When Reed finally abandoned his Hardy project he donated his notes to professor Michael Millgate, whose first book on Hardy, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, was published in 1972, with a full-blown Thomas Hardy: A Biography following in 1982.

Hardy's Secret

Self-Portrait

By HENRY REED

The Life of Thomas Hardy BY FLORENCE EMILY HARDY. Macmillan, 30s.

Many artists have led two lives, and out of consideration for their biographers they have usually contrived to lead them both at the same time. Thomas Hardy also had two lives, but they were inconveniently placed end to end.

There is a great division in his life round about 1897 when he ceased to be a novelist and returned to poetry. Biography of him will always be, from the point of view of shape, bedevilled by this fact.

There is plenty of incident, movement and emotional adventure in the first 57 years of his life. In the last 30 years that remained to him—from his own point of view his most valuable creative years—biographically dramatic landmarks are few indeed.

Official Life

The present volume suffers unavoidably from this tailing away of interest. It is the "official" life, originally published in two parts, the first in 1928 within a few months of Hardy's death, the second in 1930.

The work is still attributed on its title page to the second Mrs. Hardy, and we are left to wonder how its publishers have never got wind of the real facts of its composition, which were divulged as long ago as 1954 in Richard L. Purdy's monumental bibliographical study. The Life of Thomas Hardy is, in fact, save for its last four chapters, Hardy's own autobiography, and should be announced as such.

It is, by any standards, a ramshackle work, and its information is in may places demonstrably inaccurate even where there seems no point in disguise. But the book is packed with a miscellany of information not available elsewhere, and readers who care for Hardy will find it everywhere endearing, engaging, and full of his characteristic humour:

"There are two sorts of church people; those who go and those who don't go: there is only one sort of chapel-people; those who go."

There is, above all, the sense of being "with" Hardy himself: every page is invested with his own idiosyncrasies of vision and style.

Dorset Childhood

The early chapters are particularly impressive. He recreates his childhood and youth in Dorset and his days in London with fair objectivity. There is much room for correction of fact, but in mood and atmosphere his own account will scarcely be bettered.

Part of its charm comes, I think, from Hardy's genuine and characteristic modesty of manner. He was well on into his seventies when he embarked on the work, yet he never indulges in the reminiscent pride we so often have to wince at in writers' memoirs.

And there is no trace of that excessive self-esteem which sometimes indicates an unconscious sense of failure and is so painful in (to come no nearer to home) a writer like Bernard Shaw.

All the same, there is much that is defensive in these pages, and this provides strange matter for study. A good deal of care seems to have been taken to make things opaque when Hardy wished them to be.

Blank mendacity he rarely has recourse to: on the whole he probably tells fewer lies than most people. But he is at pains to mislead us about things that had affronted him in the circumstances of his own life or worried him in his relations with the highly class-conscious society of his time.

It is in his art that find the rectification of these evasions and deceptions. His art might often be bad art, its badness the more conspicuous for lying cheek by jowl with his incomparable best. But it was faithful to his own experience, and the recurrent themes of his fiction were the basic themes of his own life.

The contrast of humble birth and lofty aspiration, the struggle for education and learning, the uncertainty of passion, the dissatisfaction with marriage as solution to the problem of sex, the commonness of external adversity and of simple bad luck—all these went into his novels and his poems.

There is little or nothing of them, however, in the official life; and we are at times as conscious of this little-or-nothing as we would be if there were whole blank pages in the book.

Meant as Protest

However, the thing was not meant as confession: nor was it undertaken with any marked relish; quite the contrary. It came into being largely as a protest against recurrent public mis-statements about Hardy's own experiences. It was not meant to be a source for future biographies: it was meant to be an obstacle in their way.

So far it has proved highly successful in this aim. The biographical studies of Hardy published since his death compete lamentably with each other in the inaccuracy of their employment both of the "official" material given here and of the other pieces of significant information that seeped out in more recent years.

In the circumstances this republication—in a very convenient form—of Hardy's own account of himself is, for all its defects, a timely and refreshing recall to order.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

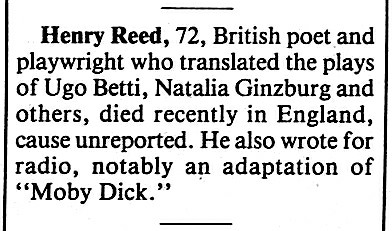

An obituary for Henry Reed appears in most surprising place: the classic New York/Hollywood entertainment rag, Variety. How does an arguably obscure British poet rate such an honor, might you ask? Because of Reed's surge of translations of Italian plays for the stage in London during the mid-1950s, which culminated in a New York production of Ugo Betti's Island of Goats at Broadway's Fulton Theatre in October, 1955. The play was a box office disaster and closed after only four days, resulting in the trademark varietyese™ headline:

Anyway, Foreign Crix Liked Flopperoo 'Goats'

Anyway, Foreign Crix Liked Flopperoo 'Goats''Island of Goats,' a recent flop on Broadway, had foreign appeal on both sides of the Atlantic. Having previously clicked in Paris, the show repeated with the foreign press reviewers in N. Y. It drew unanimous pans from the first-string Broadway critics.

The Ugo Betti drama, adapted by British playwright Henry Reed, folded Oct. 8 at the Fulton Theatre, N. Y., after seven performances. Following the windup performance, Saul Colin, a member of the Stage & Screen Foreign Press Club, took over the stage to praise the play, noting that 80% of the foreign publication aisle-sitters had turned in favorable notices.

Colin also shook hands with the entire cast, who had been standing on one foot and then the other.

[October 19, 1955, p. 71]

And here's Reed's aforementioned Variety obit, from the New York edition, January 7, 1987, p. 151:

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

The Royal Literary Fund was founded in 1790 by the minister and philosopher David Williams, who sought to create a means of aiding and assisting authors in financial distress. The impetus arose from the tragedy of Floyer Sydenham, an Oxford fellow and translator of Plato, who died in debtor's prison.

The RLF can rank among its beneficiaries such luminaries as Leigh Hunt, Joseph Conrad, Mervyn Peake, and James Joyce; as well as the widow of Robert Burns. Originally financed by subscribers, today the Royal Literary Fund counts amongst its income the estates of A.A. Milne, Rupert Brooke, G.K. Chesterson, and W. Somerset Maugham. The Fund was able to add "Royal" to its title in 1842, owing to the support of Prince Albert. An excellent short history of the RLF is available on their website as a .pdf.

The Royal Literary Fund currently manages permissions for use of Henry Reed's poems and plays. As a not-for-profit organization, the Fund must report its income to the Charity Commission, which registers and regulates charities in England in Wales. On the Charity Commission's website are financial statistics, as well as annual reports. In the latter, we can glean some numbers for Henry Reed's annual royalty income since 2004:

2011: £1,411 (~$2,284)

2010: £1,288 (~$1,993)

2009: £270 (~$418)

2008: £1,835 (~$2,840)

2007: £2,185 (~$3,381)

2006: £1,543 (~$2,388)

2005: £706 (~$1,093)

2004: £1,948 (~$3,015) In 1946, Reed surmised that a writer might survive on £1,000 a year. He might have settled for W. Somerset Maugham's royalties, which amounted to £139,723 in 2011, or the profits from the Pooh Properties Trust, which took in £127,500. Or, perhaps, he could take comfort in the fact that Rupert Brooke himself made a mere £220.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

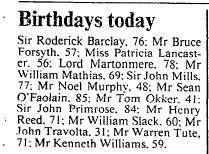

Henry Reed was very much in demand in 1973. He made at least three public appearances that year: the first, in May, was "Poets in Person" with Édouard Roditi, at the Poetry Society. In October, Ian Hamilton organized "The Poetry of War" at the Mermaid Theatre, with Charles Causley and Roy Fuller.

On Tuesday evening, September 25, 1973, we find Reed at a reading hosted at The Pindar of Wakefield pub, bringing with him an "unpublished war poem" to share. This announcement appeared in The Observer on September 23:

The Pindar of Wakefield could boast of being established in 1517, although the current building was constructed after a fire in 1878. A pinder (or pinner) was a person employed to impound stray cattle and to look after the pound. The pub takes its name from a traditional ballad about a mythical Wakefield pound-keep who resisted Robin Hood. As an underground music venue, its stage has been graced by the likes of Bob Dylan in 1962, The Pogues in 1982, and Oasis in 1994. In 1986 it became The Water Rats Theatre Bar, and it's now the Monto Water Rats:

[Water Rats Theatre Bar, St Pancras,

WC1, by Ewan-M.]

The International Who's Who in Poetry (1972), has this entry for The Cool Web:

Organizer, Hugh Dickson, The Pindar of Wakefield, 328 Grays Inn Road, Kings Cross, London. The Cool Web is a platform for good verse from all sources to be presented in a relaxed atmosphere. A small group of experienced readers, all professional actors, select a programme and are joined by a well-known poet. The guest poet is invited to use one part of the evening in any way he likes: to read his own poems or other people's, to make critical, political or polemical points, to involve the actors, or to integrate with the rest of the programme.

Successful programmes have already taken place, featuring Alan Brownjohn, George MacBeth, Peter Porter and Anthony Thwaite. Some time is also set aside for readings from the audience.

The group meets at 8 pm every Tuesday at the above address and is organized by Hugh Dickson, 4a Colinette Rd., SW15, and David Brierly, 1 Zenobia Mansions, W14.

"The Cool Web" comes from a line in the Robert Graves poem with that title: "There's a cool web of language winds us in...".

Given Reed's affinity for the stage (and for actors), it sounds like a staggering (and interactive) evening. The "unpublished war poem" can be none other than the last addition to his Lessons of the War sequence, " Psychological Warfare." The notes to his Collected Poems (1991), edited by Jon Stallworthy, indicate that Reed probably worked the poem for several decades, adding and updating several drafts:

(?1950—1970). Typed draft with autograph emendations, 7 ff.; autograph note at head: "USE THIS COPY but v. pp. 6 & 7 of the other", is in shaky late hand. Earlier (?) typed drafts show minor variants. A number '5.' preceding the title would seem to indicate that this poem was once intended to form part of the sequence Lessons of the War… of 1970—indeed, the author in conversation in the 1970s mentioned that such an afterpiece had been composed. [p. 163]

It would seem Reed intended, or at least, hoped, ultimately, for "Psychological Warfare" to be inserted before "Returning of Issue," the closing poem in the series. "Returning of Issue" was published in 1970 both in the Listener and the collected Lessons of the War (New York: Chilmark Press), although a version was included in a reading of "The Complete Lessons of the War" on BBC radio in 1966. In fact, in this archive of radio scripts produced by Douglas Cleverdon, there are two unscheduled "Complete Lessons" listed (is a recording implied?), one of which includes "Psychological Warfare" as early as 1965: Box 4 F223 unscheduled [1965] Reed, Henry. The Complete Lessons of the War. I. Naming of Parts, II. Judging Distances, III. Movement of Bodies, IV. Unarmed Combat, V. Psychological Warfare, VI. Return of Issue. Read by Reed and Frank Duncan. TLO 531/697 The poem remained unpublished in Reed's lifetime, and did not appear in print until 1991, when the London Review of Books published it to herald the arrival of the Collected Poems. An acquaintance of Reed's from Birmingham (and later, Bletchley Park), however, wrote to the LRB when the poem appeared to suggest that work on "Psychological Warfare" had actually been begun before the end of the Second World War ( previously). In any case, it survives as a masterpiece of Reed's inability to self-censor or cut from his work. The Lessons of the War progress from "Naming of Parts," at 30 lines long, to this 21-stanza monster of 253 lines. I can't imagine reading the entire poem to a live (or radio) audience, despite how funny it may be.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

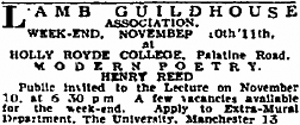

Here, in an announcement from the Manchester Guardian from November 5, 1945, we find Henry Reed a good deal north of his normal environs, giving a lecture on modern poetry near Withington, outside Manchester proper:

The Lamb Guild, according to their website, was founded in 1938 by the University of Manchester's department of Extra-Mural Studies to make residential continuing education available to local adults through lectures, conferences, and field trips.

The location given in the ad on Palatine Road is the Holly Royde mansion, which you can still see today via the magic of Google Maps.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

Covering and recovering some old ground today, when up pops a short but pithy bio in this rare anthology: The Voice of Poetry, 1930-1950, edited by Hermann Peschmann (London: Evans Bros., 1950). The book includes Reed's "Naming of Parts," but Peschmann seems to have taken the time to personally poll his contributors for personal information:

Reed, Henry. Born 1914 in Birmingham and educated there, inc. Birmingham Univ. Called up 1941, went to Foreign Office 1942—6. Since then whole-time writer—but says he is a slow worker. Broadcasts on books and films and enjoys writing radioscripts on extended themes, e.g. Moby Dick. Fond of films, theatre and opera, and of playing the piano badly and for long stretches of time. One verse book: A Map of Verona (1946). [p. 239]

Peschmann was, for a time in the 1940s, a lecturer in English literature for the Adult Education Department of Goldsmith College, University of London, known as a critic and for his correspondence with Dylan Thomas and others.

This anthology was published in 1950, so Reed's BBC radio adaptation of Moby Dick (January, 1947), Pytheas: A Dramatic Speculation (May, 1947), and The Unblest: A Study of the Italian Poet Giacomo Leopardi (May, 1949) would have been his only features thus far. Reed's love of theatre (and actors), opera, and film are well-documented in his letters and book reviews, and he often lamented his meticulous, plodding writing process, but the fact that he played the piano, however poorly, is actually news to me.

This tiny tidbit is so heartbreakingly personal—paraphrased from a letter or questionnaire or phone call to Reed—it's tempting to try and track down a copy of the book.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

While we're on the subject of Reed failing to turn up for engagements 1 2, it would seem germane to mention this famous anecdote related by Derwent May, former literary editor of the Listener (1965-1986) and the Sunday Telegraph (1986-1989):

This story gets repeated in Reed's 1986 Guardian obituary, and I had originally seen it told with Douglas Cleverdon, Reed's frequent radio producer, as the one who was stood up.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

A quick follow-up to follow through on my previous post on 1975's fourth annual " Poems for Shakespeare" — an event overshadowed by the death of Veronica Forrest-Thomson. I managed to borrow a copy of the resulting anthology. Here's the relevant part of Anthony Rudolf's introduction:

The public reading of Poems for Shakespeare (part of the Shakespeare birthday celebrations presented by Mr Samuel Wanamaker assisted by Ms Maggie Southam) took place on April 26, 1975 in the retrochoir of Southwark Cathedral. The evening began and ended with Shakespeare settings by Robert Johnson, Sibelius, Thomas Morley, and Rodney Greenberg (the world premiere of his 'Helen's Blues' with words from All's Well . . .), all sung by Helen Sava accompanied on the lute by Michael Hunt and on the guitar by Kevin Peake. This was the fourth annual Poems for Shakespeare. It is a matter for rejoicing that such an event is thinkable at this time — that it takes place is a tribute to poetry, to Shakespeare's genius and to Sam Wanamaker's vision and seriousness of purpose.

The 'commission of thy years and art' (to quote Romeo and Juliet) had involved (and I quote one variant of the letters I wrote to the poets) re-reading 'a Shakespeare play of your choice' and writing 'a poem out of that experience' (or in Sydney Carter's case a song). 'Naturally I am not asking for a direct response (unless you want that) but a poem of any kind that the re-reading inspires or suggests.' In addition to a poem, the poets were requested to select and read a passage from their chosen play — possibly a passage which connected in some way with the poem.

I received poems from ten of the twelve poets who were listed in the programme. Two — in the end — were not able to come up with poems. One of the ten poets did not turn up on the evening of the 26th. After the interval, when her turn came to read, I asked if she was present. Not receiving an answer, I asked two members of the audience (whom I had primed during the interval), the actress Elaine Ives Cameron, and the poet Christopher Hampton, to read Veronica Forrest-Thomson's poem and Shakespeare extract respectively. I was worried and at the same time irritated, and I expected some explanation or reason, within a day or two, for her absence. The next day a friend and colleague of hers and mine telephoned to ask if I knew where she was: her parents had been in the audience he told me, and now, twenty-four hours later, still didn't know her whereabouts. Three days later he wrote to me to say that Veronica had died the day before the reading. She was 28.

Tony Harrison, it would seem, was the other poet (besides Reed) who failed to produce a new poem before the event.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

Another no-show, it would seem. Reed's name turns up in a (December?) 1962 issue of the Poetry Book Society Bulletin:

Festival of Poetry,

Festival of Poetry,

1963Arrangements are now taking shape for the Festival of Poetry to be held at the Royal Court Theatre, Sloane Square, London, SW1 from Monday to Saturday, July 15th to 20th, 1963. Patric Dickinson has been appointed Director, and a Festival Advisory Committee set up under the Chairmanship of John Lehmann.

There will be two separate programmes each evening: the first at 6.30 pm and the second at 8.40 pm. Each programme will be carefully planned to illustrate some aspect of poetry today. Special sessions will be devoted to Ballads, Poetry and Music, Dramatic Verse, American Poetry and Foreign Poetry (in translation). The Apollo Society and P.E.N. have agreed to co-operate in two of the programmes. It is intended to commission new work which will be heard for the first time during the Festival.

Among the poets and artists who it is hoped will take part are Dannie Abse, Lennox Berkeley, Clifford Dyment, Patrick Garland, Marius Goring, Ted Hughes, Penelope Lee, Elizabeth Lutyens, Ewan MacColl, I. M. Parsons, Sylvia Plath, William Plomer, Sir Michael Redgrave, Peter Redgrove, Henry Reed, Dame Flora Robson, Paul Roche, Alan Ross and Stevie Smith. A leaflet giving fuller particulars will be issued in the spring. , the souvenir booklet for the festival, however, does not include Reed as a participant, but contains poems by Patricia Beer, Alan Brownjohn, Hilary Corke, Clifford Dyment, Roy Fuller, Michael Hastings, C. Day Lewis, Christopher Logue, William Plomer, Peter Porter, Peter Redgrove, Paul Roche, Stevie Smith, and Terence Tiller, as well as an introduction by T.S. Eliot. The Poetry Book Society was founded in 1953 by Eliot and friends, to "propagate the art of poetry" (check out their online bookshop!).

Unfortunately, this is yet another episode which cements Reed's reputation as a procrastinator and perfectionist who would rather not produce anything at all, rather than share a poem he considered to be unfinished.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

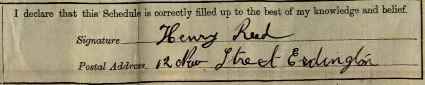

It's nice when the little things can still make you happy. The littlest of things. Thimbles. Banker's clips. Very small rocks. Or how about, let's say... the oldest citation for Henry Reed to appear in print?

The Bookman ("I am a Bookman." — James Russell Lowell) was a monthly literary magazine published in London by Hodder & Stoughton from 1891 until 1934. Essentially a catalog of their forthcoming books and publications, it also contained reviews, bibliographies, advertisements, and illustrations. Like most magazines of the time, The Bookman staged a continuous variety of writing competitions, inviting submissions on such varied subjects (some of which pertained to the issue in hand) as: "best original lyric"; "best epigram on an Income Tax Collector"; "best acrostic on the name of any author mentioned"; "best review, in not more than one hundred words, of any recently published book"; "best 14 lines of verse containing the largest number of examples from the winning list of hackneyed quotations from the competition in the previous number"; etc. Prizes for the winning entries ranged from half a guinea to up to a gift of three new books. Runners-up might be selected to appear in print.

The October, 1928 issue included the following long-running competition:

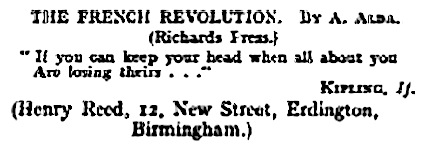

A Prize of Half a Guinea is offered for the best quotation from English verse applicable to any review or the name of any author or book appearing in this number of The Bookman.

Winners were listed the next month, in November. The entry which received the half-guinea came from one B.M. Beard of Bexleyheath, Kent, with a lyric from Ruddigore by Gilbert and Sullivan: '...blow your own trumpet, / Or, trust me, you haven't a chance!' as it applied to the book How to Secure a Good Job, by W. Leslie Ivey (London: Sir I. Pitman & Sons).

And there, among the runners-up, receiving the consolation prize of being "selected for printing," is the submission of one Henry Reed of Erdington, Birmingham, chosen for his take on the title of André Alba's The French Revolution (London: Richards Press): 'If you can keep your head when all about you / Are losing theirs...'. Reed was fourteen years old:

This tiny portrait is exciting for several reasons: Reed was barely a teenager in 1928, attending King Edward VI Grammar School in Aston, Birmingham, and yet here he is, reading and following a London literary magazine, already adept at wordplay and pun construction. He would eventually win a 1941 New Statesman competition calling for parodies of T.S. Eliot. Kipling's poem, " If—," was first published in 1910, and it quickly became (and still remains) not only Britain's favorite poem, but Britain's most-parodied poem. It must have been taught in every classroom and repeated at every recital during Reed's childhood. (See the terrific digital collection for "If—" at Dalhousie University, with images of both broadsides and multipage editions.) Finally, this is the only record I've found in print of Reed using the address of his childhood home in Erdington.

I had to look up the value of the prize, to see just how heartbroken Reed must have been when he lost the competition. Half a guinea was the equivalent of 10 s 6 d, or 55p. It would have been worth about the cost of a brand new novel.

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

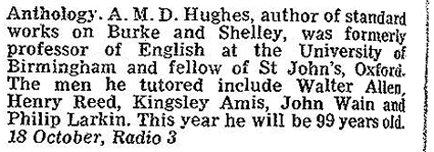

In his article, "John Clare's Learning," published in the John Clare Society Journal in 1988, Eric H. Robinson relays the following anecdote:

I remember the poet, Henry Reed, telling me of a professor at Birmingham University, where Reed studied, who told him that he must correct his grammar before he could become a poet. Reed did so: Clare not only did not do so, but after some early attempts resolutely refused to comply. [p. 11]

Henry Reed attended the University of Birmingham from 1931 until 1936. Who was this professor who taught him proper grammar and helped mould him into a modern poet? An answer appears in The Listener for September 28, 1972, in the schedule of upcoming radio programmes:

You can browse the rather daunting list of Hughes's books and publications on WorldCat. Anthony Thwaite, reviewing recent radio for The Listener on October 26, had this to say about the formidable professor's appearance:

The strangest and certainly most moving talk programme of the week was A.M.D. Hughes's Personal Anthology on Radio 3, which among other things demonstrated—in this period of celebration, when the supposed golden age of radio must often be sounding on tin ears—that old men do not forget. Hughes, approaching his 100th year ( Radio Times got this right but R.D. Smith, introducing him on the air, managed to lop off a decade), used to teach English to, among other, the young Henry Reed and Kingsley Amis. He recited out of his blindness Hardy, Milton, Wordsworth, Arnold and Shelley, with an exalted and totally unfashionable inflection that demanded complete attention. He certainly got mine. For his performance of 'The Convergence of the Twain' alone this programme deserves a place in the archives, along with those crackling atmospheric fragments of Browning and Tennyson. ["Jabbering Set," p. 560]

Incidentally, R.D. "Reggie" Smith also would have been a student of Hughes's at Birmingham, along with Reed and Walter Allen. Arthur M.D. Hughes died on January 11, 1974. His obituary appeared in The Times, the following Monday:

PROFESSOR A. M. D. HUGHES Professor Arthur Montague D'Urban Hughes, Emeritus Professor of English at Birmingham University, died on Friday at the age of 100. He was widely known for his critical book The Nascent Mind of Shelley, published when he was 74.

Hughes was born at Worthing, Sussex, on November 3, 1873, the son of the Rev Edwin M. M. Hughes. He was educated at St Edmund's School, Canterbury, and St John's College, Oxford, and became a lecturer for Oxford's Extension Delegacy. He was English Lektor at Kiel University 1905-14 and a member of the staff of Oxford University Press 1915-21.

He was a lecturer in English at Birmingham from 1921 to 1931; and he lectured at St John's College, Oxford, from 1923 to 1929. He was appointed Reader in English at Birmingham in 1931 and Professor of English Language and Literature in 1935, retiring in 1939. He was made emeritus professor in 1940.

He married in 1906 Wilhemina Langenheim, of Kiel, Germany, and they had a daughter.[January 14, 1974, p. 14]

Eric Robinson also mentions Reed in his acceptance speech for the Leonardo da Vinci Medal, given at the awards banquet of the annual meeting of the Society for the History of Technology in Las Vegas, in 2006:

I began my life of archival research in the Birmingham City Reference Library at the age of eleven, when I went there in the evenings to do my homework. A happy, rotund lady called Miss Norris used to help me by bringing me books, but also manuscripts from the Boulton and Watt Collection. As a junior librarian (aged sixteen), she herself had compiled the first catalog of that great archive, and it was amazing what she could find in it. It's one thing to read about James Watt's engines, and another to look at the splendid colored drawings that Watt submitted in order to get a patent. A few years later, I was being taught at King Edward VI Grammar School in Aston, Birmingham, by the poet Henry Reed. He introduced me to the poetry of Auden. I read for the first time poetry whose visual images reinforced my own daily experiences...[.] [Technology and Culture 48, no. 1 (2007): 133]

And so the circle of teaching is complete!

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

Sometimes, the quest for Reed means discovering exactly where he wasn't on a given day.

In April of 1975, the World Centre for Shakespeare Studies, headed by Sam Wanamaker, presented the fourth annual Shakespeare Birthday Celebrations. Events that year included a two-month exhibition of "Shakespeare Round the Globe" at the Bear Gardens Museum (now Shakespeare's Globe), a gala concert of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra—featuring the Huddersfield Choral Society (conducted by John Pritchard), Ermano Mauro, Richard Briers, Judi Dench, Richard Johnson, Barbara Leigh-Hunt, Spike Milligan, Leo McKern, Richard Pasco, and John Stride—performing at Royal Festival Hall, and a concert of "Shakespeare jazz" at Southwark Cathedral (directed by Neil Ardley and coordinated by Ian Carr), with performances by Roy Babbington, Pete and Pepi Lemer, Henry Lowther, John Marshall, Dave Macrae, Paul Ruthorford, Alan Skidmore, Chris Spedding, Trevor Tomkins, Ray Warleigh, and others.

Concluding the festival was a poetry recital on the evening of April 26: "Poems for Shakespeare IV," also staged at Southwark Cathedral. Scheduled to read were Keith Bosley, Ernest Bryll, Sydney Carter, Veronica Forrest-Thomson, Erich Fried, Tony Harrison, John Heath-Stubbs, Jon Silkin, Ken Smith, Val Warner, Augustus Young, and Henry Reed, delivering poems commissioned specially for the event. Musical accompaniment was provided by Helen Sava and Michael Hunt.

Advertisement from The Spectator, April 26, 1975.

I was initially excited that Reed had made an appearance—possibly with a new poem—but I was skeptical. An anthology of pieces from the recital, Poems for Shakespeare 4 (Anthony Rudolf, ed. Globe Playhouse Trust, 1976), was released the following year, but Reed is not listed among the contributors. From British Book News:

This is the fourth collection of poems based, however intimately or remotely, on the experience of reading Shakespeare's plays; they were originally read as part of the Shakespeare birthday celebrations at Southwark Cathedral last year. Ten poets are each represented by a single poem, ranging from a vigorous, straightforward and pleasantly ironical ballad by Sidney Carter [sic] to a strange elliptical and disturbing meditation by the late Veronica Forrest-Thomson. My own favourites are 'Winter in Illyria' by John Heath-Stubbs and 'Winter Occasions' by Ken Smith. Anthony Rudolf's introduction is oddly aggressive except where it pays deserved tribute to Miss Forrest-Thomson.

Further research on the event turned up this excerpt from Augustus Young's memoir, Chronicling Myself, wherein he discusses "Veronica" (at the bottom of the page):

Her paradis artificiels were cut short two years later. At 'Poems for Shakespeare' in Southwark Cathedral I stood at the back, breathing the air coming up off the river. On the Tube home, Eddie Linden told Tony and myself that he saw Veronica in one of the cloisters, but she had disappeared before her turn came to deconstruct Shakespeare. That was the night of her suicide.

She lives on, on the tip of the tongue of the L-a-n-g-u-a-g-e poets.

Veronica Forrest-Thomson, an influential poet, is best known for her book of criticism, Poetic Artifice (Manchester University Press, 1978). Jacket Magazine had an issue devoted to Forrest-Thomson, in 2002. (It's my understanding that her premature death at the age of 27 is now considered to be accidental, rather than suicide.)

I sent Augustus Young an e-mail to see if he could tell me anything of Reed reading at "Poems for Shakespeare" in 1975. Mr. Young thoughtfully forwarded me to Anthony Rudolf, who had directed the event that year. Mr. Rudolf's gracious reply told me what I had already feared: Henry Reed did not appear; he was in hospital with one of his chronic illnesses, and could not be finally persuaded.

|

1528. Manning, Hugo. "Recent Verse." Books of the Day, Guardian (Manchester), 31 July 1946, 3.

Manning feels that 'Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship.'

|

Did Henry Reed play a part, however small, in Vita Sackville-West's renouncement of poetry? In 1946, the Incorporated Society of Authors was charged with putting together a poetry recital of classic and modern verse for the Royal Family. A committee was convened, chaired by Denys Kilham Roberts (the Society's secretary-general), which included George Barker, Louis MacNeice, Walter de la Mare, Henry Reed, Edith Sitwell, Dylan Thomas, and Sackville-West.

Vita Sackville-West (cousin to Edward "Eddy" Sackville-West) was a prize-winning author and a poet, famous for her bisexual romances, including a long relationship with Virginia Woolf. By 1946 she had published fourteen novels, five scholarly biographies, and ten volumes of poetry (not including a Collected Poems in 1933).

In Henry Reed's review of Walter de la Mare's Complete Poems ( The Sunday Times, January 15, 1970), Reed makes mention that his first and only meeting with de la Mare took place at one of the meetings of the Poetry Committee:

On the one occasion I had the honour of meeting de la Mare—after some rather fractious gathering convened to decide which verses in our language might not be too tedious or indecent for the young ears of the Royal Family—I fervently recorded this fact to him. He was too modest to believe it; but eagerly, in a damp, dark Chelsea street, he told me of the barely credible circumstances of his first meeting with Hardy, in 1921.

It may be, perhaps, that the "damp, dark Chelsea street" Reed describes is somewhere in the vicinity of the offices of the Society of Authors, 84 Drayton Gardens, London.

At least one meeting took place in the King's Bench Walk offices of Denys Kilham Roberts, barrister at law; in order to choose which poems would be read at the recital, and by whom. In Victoria Glendinning's biography, Vita: The Life of V. Sackville-West (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1983), we have this account:

In March she went to a meeting of the Poetry Committee of the Society of Authors, chaired by Denys Kilham Roberts at his rooms near Harold's [her husband, Sir Harold Nicolson] old apartment in King's Bench Walk. The committee—which included Edith Sitwell, Walter de la Mare, Henry Reed, Dylan Thomas, Louis MacNeice and George Barker—was to plan a poetry reading to be held at the Wigmore Hall in the presence of the Queen. Vita made no comment in her diary at the time; only in 1950, in depression, did she write: 'I don't think I will ever write a poem again. They destroyed me for ever that day in Denys Kilham Roberts' rooms in King's Bench Walk.' (p. 341)

Sackville-West, whose long poem The Garden (London: Michael Joseph, 1946) was just about to be published, was not selected to read her verses for the Queen. "I am prepared to devote all my energies to the garden, having abandoned literature," she wrote, despairingly (Glendinning, p. 341). In truth, she was to end up devoting all her literary energy to gardening: in 1947 she began an immensely popular column for The Observer called "In Your Garden," and the following year became a founding member of the National Trust's garden committee. As a matter of fact, when I was attempting to define the species of flowers in Reed's "Naming of Parts," I turned to the second of Sackville-West's collected essays, In Your Garden, Again (London: Michael Joseph, 1953):

October 14, 1951 It started its career as Pyrus Japonica, and become familiarly known as Japonica, which simply means Japanese, and is thus as silly as calling a plant 'English' or 'French.' It then changed to Cydonia, meaning quince: Cydonia japonica, the Japanese quince. Now we are told to call it chaenomeles...[.] (p. 134)

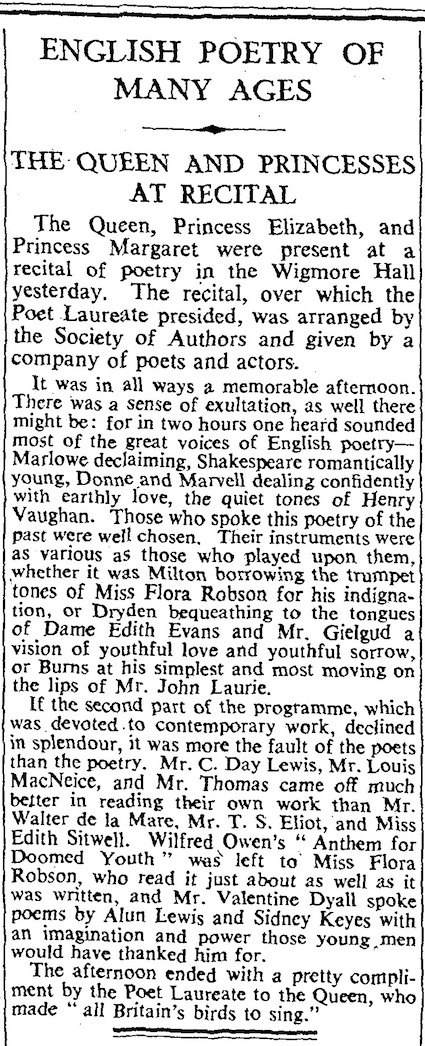

The recital took place on Tuesday, May 14, 1946, at Wigmore Hall. The Queen, Princess Elizabeth, and Princess Margaret were in attendance. John Masefield, the Poet Laureate, presided. The actors Valentine Dyall, Edith Evans, John Gielgud, John Laurie, and Flora Robson read classics of English verse, while C. Day Lewis, T.S. Eliot, Louis MacNeice, Walter de la Mare, Edith Sitwell, and Dylan Thomas presented a selection of more modern poems, which were somewhat less well-received. Thomas, apparently, "at one stage in the proceedings was seen to flick his cigarette ash in the Queen's lap" (Victor Bonham-Carter, vol. 2 of Authors by Profession. London: Bodley Head, 1984, p. 302). This announcement appeared the next day, in The Times:

|

1527. Rosenthal, M.L. "Experience and Poetry." Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review (New York), 17 October 1948, 28.

Rosenthal says Reed shares with Laurie Lee 'that unhappy vice of young intellectuals—a certain blandness of which the ever-simple irony is a symptom.'

|

Well, what have we here? In the pages of Italy Writes: A Review for Those Who Read ( L'Italia che scrive; rassegna per coloro che leggono), the journal of the Leonardo Foundation of Italian Culture, Rome ( Fondazione Leonardo per la cultura italiana), an announcement from a 1947 Italian writers' festival ( Settimana degli scrittori):

Dal 24 al 26 settembre si è svolta, sempre in Perugia una Settimana degli scrittori, con relazione di Giacomo Debenedetti sul Teatro e romanzo della realtà e teatro e romanzo dell'esistenza. Erano presenti il poeta inglese Henry Reed, il prof. Kardos, studioso dell'umanesimo in Ungheria, nostri letterati, critici, scrittori e filosofi come Bellona, Toschi, Della Volpe, Tecchi, Banfi, Contini, Capitini, Bigiaretti, Mila, Ronga, Vigorelli, Cantoni, D'Amico, Pandolfi, Guerrieri.

Which roughly translates as: "From September 24 to 26 took place, again in Perugia a Week of the writers, with relation of Giacomo Debenedetti on the theatre and novel of truth, and the theatre and novel of life. Those present included the English poet Henry Reed, Professor Kardos, a scholar of humanism in Hungary, our writers, critics, and philosophers such as Bellona, Toschi, Della Volpe, Tecchi, Banfi, Contini, Capitini, Bigiaretti, Mila, Ronga, Vigorelli, Cantoni, D'Amico, Pandolfi, Guerrieri."

Emphasis mine, of course. If anyone has a better grasp of Italian, I'd encourage you to leave a comment or drop me an e-mail!

We had previously found Reed talking about having attended the Festival of Sacred Music in Umbria, held at about the same time, from September 21 through October 5, 1947. I believe the concurring writers' festival in question has evolved into the Umbria Libri, an annual book festival in Perugia.

|

1526. Blunden, Edmund. "Poets and Poetry." Bookman, n.s., 1, no. 4 (July 1946): 14-15.

Edmund Blunden says Reed's Lessons of the War poems 'have captured something of the time-spirit and ambiguity of the recent war in a style of wit and deep feeling united.'

|

Henry Reed spoke Japanese. Yet, as far as I know, he never hints at this particular skill in any of his poems, prose writing, or the scripts for his radio plays. The fact, however contradictory, remains. Henry Reed was a Japanese linguist for the latter part of World War II.

This is repeated in several places, the genesis of which appears to be Reed's obituary in the Times of December 9, 1986:

Called up in 1941, he served—'or rather,' he himself wrote, 'studied'—in the Army, until 1942 when he was seconded to Naval Intelligence at Bletchley. The 'studied' is perhaps explained by the crash-course he underwent in Japanese, and he served out the rest of the war teaching that language to Wrens.

The quotations are from Reed's self-scribed entry for Who's Who. There seemed to be few sources which could illuminate this period in Reed's life, considering the secrecy surrounding the codebreaking efforts at Bletchley Park during the war. Then suddenly, quite recently, there materialized an article in the most unlikely place, Significance, the journal of the Royal Statistical Society: " Edward Simpson: Bayes at Bletchley Park" (June 2010, pp. 76-80), a memoir concerning the implementation of Bayes' Theorem in cracking the Japanese JN-25 and German Enigma codes, by the statistician Edward H. Simpson. "[H]ere, because I know it at first hand," Simpson says, "I describe the use made of Bayes in the cryptanalytic attack on the main Japanese Naval cipher JN 25 in 1943-1945, by the team in Block B which I led." This definitely raised my interest, for we know from the Bletchley Personnel Master List that Reed was assigned to Block B, Naval, for at least part of the war.

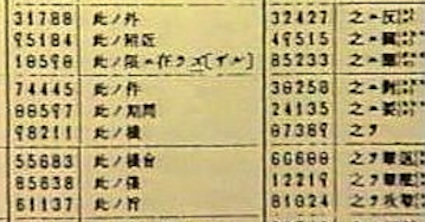

Unlike the German Enigma code, famously enciphered on the eponymous machine, the JN-25 code used by the Japanese Navy utilized a pre-selected vocabulary in printed codebooks, with corresponding values of five-digit numbers to be substituted for the words being transmitted. A bit of tricky addition then took place, resulting in a very secure coded message (albeit with a fatally exploitable flaw).

For an overview of the mathematics Simpson describes being utilized in breaking the Japanese code, you can read John Graham-Cumming's (author of O'Reilly's Geek Atlas) blog post, " Bayes, Bletchley, JN-25 and a 'Modern' Optimization." What grabbed my attention, however, wasn't the inscrutable math, but Simpson's colorful anecdotes of wartime life at Bletchley Park, and the great "diversity of minds" working (and playing) together:

Off-duty we mixed freely. With almost no contact with the people of Bletchley and the surrounding villages, and most of us far from our families, we were a very inward-looking society. All the civilian men (except for some of the most senior) had to serve in the Bletchley Park Company of the Home Guard: this was a great mixer and leveller. On the intellectual side, chess was probably the most glittering circle, with Hugh Alexander, Harry Golombek and Stuart Milner-Barry at its centre...[.] There was music of high quality. Myra Hess visited to give a recital. Performances mounted from within the staff included 'Dido and Aeneas', Brian Augardeís jazz quintet and several satirical revues. A group of us went often by train and bicycle to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon. Scottish country dancing flourished. The Hall, which was built outside the perimeter security fence so that Bletchley people could use it too, provided for dances as well as the performances and a cinema. One memorable occasion was the showing of Munchhausen, in colour (probably the first colour film that most of us had seen) and in German without subtitles. I heard no explanation of how it came to be at Bletchley Park. I doubt that it was through the normal distribution channels. [p. 79]

Simpson concludes (after much elaboration on letter frequency, probability, alignments, and Bayes factors) with a few reminiscences on where staff went after the war, including:

Henry Reed, a Japanese linguist while in our JN 25 team, went back to poetry, radio plays and the BBC. His 'The Naming of Parts', which has been called 'the best-loved and most anthologised poem of the Second World War', voices his reflections while serving in the Bletchley Park Home Guard. [p. 80]

How, exactly, did Henry Reed—a Classics scholar fluent in Italian and French, who had taught himself Greek in grammar school—become a linguist on Edward Simpson's Japanese Naval team? Reed had been sent up from the Royal Army Ordnance Corps in 1942, to translate Italian intercepts at Bletchley Park. Following Italy's surrender in September 1943, the bulk of Bletchley's Italian section was absorbed into the Japanese teams. This required that Reed take (or be forcibly given) an intensive, six-month "crash-course" in Japanese. The Japanese course was the brainchild of Col. John Tiltman, who had challenged a retired Naval officer, Capt. Oswald Tuck, to create and head the Bedford Japanese School. Eleven such courses were given in Bedford between 1942 and 1945, beginning in rooms above the Gas Company showroom in Ardor House (under the watchful eye of Mr. Therm), on the corner of The Broadway and Dame Alice Street (opposite the statue of John Bunyan), moved to a house at 7 St. Andrews Road, before finally settling in at 52 De Parys Avenue. Of the 255 students rushed through the school, only nine failed to pass.

Bernard Keefe recollects, in The Emperor's Codes: The Breaking of Japan's Secret Ciphers (Smith, ed., 2001):

The Japanese course was held in a large house in De Parys Avenue, Bedford. We lived in digs. As you entered the house the Japanese course was on the left and a codebreaking course on the right. We knew each other, of course; one of the code-boys was Robert Pitman, a passionate lefty who turned into a right-wing columnist for the Daily Express. But even at that stage it was remarkable that we didn't discuss each other's activities. I was interested in music and had started singing as a baritone at school. Bedford was like musical heaven, because the BBC Symphony Orchestra had been evacuated there, giving broadcasts from Bedford School Hall, or from the Corn Exchange, and added to that were shows by Glenn Miller and his US Army Air Force Band. [pp. 236-237] similarly describes attending the fifth Japanese course—between August, 1943 and February, 1944—in his book, Codebreaker in the Far East (1989):

The course was held in a large room in a detached house in De Parys Avenue, a tree-lined road not far from the town centre. There were about 35 on the course, including two girls, all of us aged about 18 or 19, and most from university Classics courses. We eyed each other sheepishly. We realised later how sensible the intelligence service had been in choosing classicists and a few other dead-language students—for example embryonic theologians working in Aramaic—for these courses in written Japanese, and modem linguists, more accustomed to spoken languages, for spoken Japanese. If the legends are true of chefs being retrained as electricians for the Army, while electricians were turned into chefs, this was no mean achievement.

We had two instructors. The first was Oswald Tuck, a retired naval captain in his sixties, who had been persuaded to teach the first course, starting in February 1942. A bearded, spectacled, quiet and benevolent man, he had taught himself Japanese nearly forty years before, and was now in his element teaching it to others. The other was Eric Ceadel, another classicist and a student on that first course; quick, cool, lucid and methodical. Inevitably he became known as 'Chūi', the Japanese for lieutenant. Later they were helped by David Hawkes.

We worked every weekday, with just enough time at coffee and lunch breaks to prevent our going stale. Most evenings and weekends were needed to learn the language and above all to memorise the characters...[.]

Many of us were music-lovers; I learned much later that chess, crossword puzzles and music had long been considered pointers to a possible proficiency in codebreaking. Several played instruments, and I believe Michael Herzig was the accomplished horn-player whose arpeggios from the Mozart concerto finales often formed fanfares for the start of our classes. We were lucky in having the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Singers evacuated to Bedford and we could often get passes for the orchestral rehearsals; I remember sitting in while Henry Holst was the soloist in the Walton violin concerto, and realising for the first time that if you can sit behind the orchestra you can learn much more than from in front. One evening we persuaded Sir Adrian Boult to give an informal talk about conducting. [p. 5]

(He may not have enjoyed quite as much musical entertainment as Keefe and Stripp, if Reed was still billeted in or around Milton Keynes during this time, but we may see evidence of his connections to the BBC, with so much broadcasting from Bedford taking place.)

Stripp also provides an interesting observation in a book co-edited with F.H. Hinsley, Codebreakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park (1993), one of the best resources on British codebreaking during World War II:

A colleague has pointed out that we finished the course with a wide inter-service vocabulary (advance, submarine, aircraft-carrier, independent mixed brigade, commander-in-chief, and the like) but never learnt the Japanese words for 'you' and 'me'. Absurd as this could be for orthodox students, it made good sense for us. Personal pronouns rarely appear in army, navy, or air force signals nor in captured documents, all of which normally take the form of reports, requests, or orders. [p. 289]

This may provide at least a partial answer as to why there is no evidence of a working knowledge of Japanese in any of Henry Reed's writing: what use is any language to a lyric poet, lacking the words for "you" or "I"?

There still remains the question of the mention in his obituary of Reed having spent the remainder of the war teaching Japanese to members of the Women's Royal Naval Service (Wrens). The urtext, and final word, comes from the most reliable of witnesses: Reed's friend and fellow Brummie, the novelist Walter Allen. In his 1981 autobiography, As I Walked Down New Grub Street, Allen speaks of visiting Reed in Dorset; of Reed working on his life of Hardy—" the life of Hardy"—even as late as 1971; of Reed frequently traveling to London for theatre, opera, and ballet (especially ballet), after the war. Allen begins:

Henry Reed had been demobilised from Intelligence, whither he had been seconded from the Army. Among other things, he had learnt Japanese, which in turn he had taught to Wrens. He intended, he said, to devote every day for the rest of his life to forgetting another word of Japanese. [p. 149]

|

1525. "Reed, Henry," Publishers Weekly, 152, no. 15 (11 October 1947), 1945.

A note on the publication of the American edition of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

I see the Google Street View car has been busy, snapping new pictures of locations across the U.K., from verge and curb. A few of these places are pertinent to our aims, such as Henry Reed's unassuming childhood home, in New Street, Erdington. Also in Erdington, along the High Street, is the former Church House (now a Savers, "Where the Smart Shopper Shops," I'm sorry to say), where Henry Reed first took to the stage, with the Highbury Players, in the early 1930s. Over in Bedford, we catch a glimpse the house in De Parys Avenue, where, from September 1943 through February 1944, following Italy's surrender, Reed attended a course at the Japanese Code School organized by the Inter-Service Special Intelligence School, as part of Bletchley Park's codebreaking efforts.

A whole gaggle of places turn up now in Dorset, including the front gate to Thomas Hardy's home, Max Gate, in Dorchester, where Reed paid a call on Hardy's widow in the autumn of 1936, while he was still hoping to produce a biography of his hero. Then, we arrive outside Yetminster's stately, 17th-century Gable Court, where Reed spent a very productive year between 1949 and 1950, until he moved to London. It was while at Gable Court (currently listed as "Milford House" at British Listed Buildings online, but the sign on the gate clearly still says "Gable Court," today) that Reed wrote his radio dramas based on the life of the Italian poet and philosopher, Giacomo Leopardi: The Unblest (first broadcast May 9, 1949), and The Monument (March 7, 1950).

Best of all, Google Street View actually helped me resolve a minor detail: the exact location of Lovell's Farm (click the minus "-" sign to zoom out) in Marnhull, which I simply could not seem to place.

Reed, accompanied by Michael Ramsbotham, rented this ample farmhouse after World War II, from as early as August or September, 1946, until possibly as late as their move to Gable Court, in early 1949. There, according to Jon Stallworthy's introduction to the Collected Poems, while Ramsbotham worked on a novel (perhaps The Parish of Long Trister), Henry Reed researched his never-completed Hardy biography, wrote book reviews for The Listener, and occasionally traveled to London to give literary and literate talks on the BBC's Third Programme. His first full-length play for the BBC, a radio adaptation of Moby Dick, was most likely completed at Lovell's Farm, being broadcast on January 26, 1947. When the play was published later that year, Reed's Preface was signed from Marnhull.

I never would have found the farm, but for the detailed description in An Inventory of Historical Monuments in the County of Dorset (1970), which allowed me to pinpoint it in Google Maps' aerial view. Even in dry, planed-and-sanded language, the house sounds absolutely heavenly:

LOVELL'S FARM (77511938), 1,000 yds. N.W. of the church [ St. Gregory's], is of two storeys with dormer-windowed attics; it has walls of coursed rubble with ashlar dressings, and roofs of tiles and stone-slates. The S. range has a symmetrical S. front and is probably of the 17th century. It was extended to the E. in the 18th century and a wing was built northwards from the E. end of the extension early in the 19th century. The original part of the S. front has a rubble plinth and is of two bays with a central doorway; above the ground-floor window heads is a continuous weathered and hollow-chamfered string-course. The windows of both storeys are of three square-headed lights with recessed and beaded stone architraves and beaded mullions; the doorway surround is similar, with the addition of a fluted keystone. Over the doorway is a segmental wooden hood with a dentilled cornice and shaped brackets. The E. extension has neither plinth nor string and the window surrounds are of wood. The N. wing is of roughly coursed rubble, with tiled roofs with stone-slate verges; the windows are of wood. Projecting N. from the W. part of the original S. range is a gabled N.W. wing. It has wood-framed windows with 18th-century leaded iron casements on the ground and first floors; the attic window has modern casements; all these openings are spanned by long timber lintels. In the E. wall is a small circular first-floor window with a recessed ashlar surround and radial leaded glazing.

Inside, the room at the W. end of the original range has 18th-century fielded panelling, in two heights, with moulded dado rails and cornices. In a cupboard beside the 18th-century fireplace are preserved the chamfered stone jamb and continuous wooden bressummer of an open fireplace. S. of the fireplace is an external doorway, now blocked up and used as a cupboard. The partition between this room and the entrance vestibule is of plank-and-muntin construction with beaded edges. Several ground-floor rooms have deeply chamfered ceiling beams. A window pane has a scratching of 1738. (v. 3, Pt. 2, "Central Dorset," p. 158)

After all my virtual driving around Marnhull, grinding gears going forwards and reversing, confirming the location was as simple as another search in British Listed Buildings. I've also gathered some screenshots taken in Street View into a Flickr set.

|

1524. Reed, Henry. Letters to Graham Greene, 1947-1948. Graham Greene Papers,

1807-1999. Boston College, John J. Burns Library, Archives and Manuscripts Department, MS.1995.003. Chestnut Hill, MA.

Letters from Reed to Graham Greene, including one from December, 1947 Reed included in an inscribed copy of A Map of Verona (1947).

|

In 1991, a veritable flurry of articles and letters relating to Henry Reed appeared in the London Review of Books, leading up to the publication of the Collected Poems. Owing to the efforts of editor Jon Stallworthy, it began in the spring of that year with a sneak peek at the only unpublished poem in Reed's Lessons of the War sequence, " Psychological Warfare" (March 21, 1991, pp. 14-15). The LRB website has an excellent search function, and I found several references to Reed I would not have been able to locate, otherwise.

The appearance of "Psychological Warfare" prompted L.W. Bailey to write in to the LRB, suggesting that Reed began the poem not in the 1950s, as Stallworthy proposes, but as early as 1944, while the two were serving at Bletchley Park ( April 25, 1991):

At the time he and I were stationed at Bletchley, he as a civilian and I as a soldier, and having been acquainted as fellow students at Birmingham University, we saw a great deal of each other. His civilian billet was a welcome refuge where I spent many congenial evenings during which he would read me extracts from work in progress, including the war poems. Some parts of the rather lengthy poem you have published seem familiar, though I could not swear to that: but I do know that he would write verse over long periods, sometimes years, before feeling he could do no more with the poem in question. I certainly think he would have revised and drastically shortened 'Psychological Warfare': but by 1950 I am sure he had put his wartime experiences well behind him.

Reed's "civilian billet," we recall, was a rooming house let by a Mrs. Buck (the mathematician Jack Good was assigned to the same house).

Lionel W. "Bill" Bailey was a well-known member of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London, and published a book of essays and observations, The Scandal Behind the "Scandal" and Other Attacks of Sherlockhomania (available from The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box). Bailey died in 2004.

In September of 1991, with Reed's Collected Poems on the verge of publication, the LRB printed Reed's poem "L'Envoi," amidst a version of Stallworthy's Introduction, "A Life of Henry Reed" (September 12, 1991, pp. 18-19). This prompted two responses. The first came from the editor James MacGibbon, who provided an example of Reed's astounding, editorial memory ("Henry Lets Her Have It," October 10, 1991):

Henry, knowing he needed some kind of psychiatric help, had read and admired the works of Melanie Klein ('Eine Kleine Nachtmusik' was the felicitous title, I think, of one of the Hilda Tablet radio series). When I told him, teasingly, that I was going to the theatre with her he asked to join us, and he did. After the performance she invited us back to her flat for coffee and little Viennese cakes. Almost before we were seated, Henry, a shy man, said: 'Mrs Klein, I want to tell you how much I admire your books.' She, who had a good sense of humour, replied, wagging a finger in amusement: 'Young man, people are always telling me that and then I find they haven't read my books!' Henry then reeled off one or two misprints with page numbers. A happy evening ended with great success!

(We shall have to add Klein's flat to our list of places Reed visited.)

This was followed closely by Ed Leimbacher, who penned a lovely reminiscence of his family's friendship with Reed, which began in 1964 when Reed was hired as a Visiting Professor at the University of Washington, Seattle (" Henry's Friends," October 24, 1991, p. 4). It remains one of my favorite discoveries.

After the publication of the Collected Poems, the critic Frank Kermode contributed a very personal review, recollecting time spent with Reed both in Seattle and London (" Part and Pasture," December 5, 1991, p. 17). Kermode makes a small but crucial error in his article, reversing Reed's substitution of "duellis" (battles) for Horace's "puellis" (girls) in the epigraph to "Naming of Parts." The mistake was caught by the historian Frank W. Walbank, though he did not realize a transposition had occurred ("Vidi," December 19, 1991).

Kermode's (corrected) article eventually became the Preface to the paperback edition of Henry Reed's Collected Poems, published by Carcanet in 2007.

|

1523. Reed, Henry. "Simenon's Saga." Review of Pedigree by Georges Simenon, translated by Robert Baldick. Sunday Telegraph (London), 12 August 1962, 7.

Reed calls Pedigree a work for the "very serious Simenon student only," and disagrees with the translator's choice to put the novel into the past tense.

|

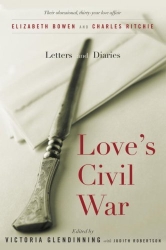

Novelist and biographer of Elizabeth Bowen, Victoria Glendinning, continues to provide new details of how Henry Reed was perceived by his contemporaries, and his visit to Ireland in the spring of 1946. I have covered here, previously, how Reed spent two weeks at Bowen's Court, Elizabeth Bowen's ancestral home in County Cork. Now, in a recent collection of letters and diary entries by Bowen and her long-time lover, Charles Ritchie, Love's Civil War (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2008, with Judith Robertson), we are privileged to discover more about how Reed's visit came about.

Star-crossed and married to other people, some context for Bowen and Ritchie's relationship is provided on the collection's front flap:

The love affair between the writer Elizabeth Bowen and the elegant and charming Canadian diplomat Charles Ritchie blossomed quickly after their first meeting in 1941 and continued over the next three decades until Bowen's death in 1973. Theirs was a passion that flourished in the heightened, dangerous atmosphere of wartime London that Bowen wrote about so vividly in her novels. When Ritchie's diplomatic career took him further afield — to Paris, Bonn, New York and Ottawa — the lovers wrote to one another continuously, sharing their hopes and fears, their boundless affection for one another, and their longing to be together again. Published for the first time in this exquisite volume, accompanied by extracts from Ritchie's remarkably candid diaries, the love letters of Elizabeth Bowen reveal a passionate, intelligent, eloquent, strong-minded and wonderfully funny woman. They also reveal a man bewitched by her writer's mind and imagination, and by her adoring vision of him as a greater man than he ever felt himself to be.

More details about Bowen and Ritchie in this Guardian review.

Henry Reed and Michael Ramsbotham traveled to Ireland in the spring of 1946, to celebrate Ramsbotham's demobilization from military service. While it's unclear if they traveled separately, or if perhaps Ramsbotham was already in Ireland at the time, in Bowen's letter we find Reed alone in Dublin, when he inquired if he might pay a visit. Bowen was already aware of Reed, as he had reviewed her collection of short stories, The Demon Lover, for The New Statesman in November of 1945. Bowen wrote to Ritchie:

Bowen's Court, Kildorrey, Monday, 20th May 1946

My darling....

The world of letters has followed me here in the person of Henry Reed, one of those young men who write for the New Statesman. He was staying in Dublin and asked if he could come here. He is one of those fascinating homosexual characters, and a very good poet — has just published a book of poems called Map of Verona. He comes from Birmingham and is of lower-middle-class origin, but has romantic aristocratic views. His boy friend, a gentle creature whom I met in London, is lurking in some other part of Ireland, waiting about for him, so I said he had better come here too: they had had some notion of a tryst in Killarney, but Henry did not seem very enthusiastic about that, and as he evidently prefers to stop here I think he had better have his friend with him. He is very good company (I mean Henry) and does not interfere with me, as he regards it as essential that I should get on with my novel. So if the boy friend, who is at present preserving a moody silence, can be traced, they are to forgather here. I wish I had Anne-Marie's [Romanian Princess Callimachi, in exile] passion for intervening in masculine love affairs, but I haven't.[...] Love from E.

[p. 91]

So, Bowen was already acquainted with Ramsbotham, as well! And we see what might be construed as the beginnings of civil war in Reed's relationship with Ramsbotham, which would only last until 1950. At the time of this letter, Bowen was writing The Heat of the Day (London: Jonathan Cape, 1949), her novel on wartime London.

In addition to her work on Bowen, Victoria Glendinning has published biographies on Vita Sackville-West, Edith Sitwell, Jonathan Swift, Anthony Trollope, Rebecca West, and Leonard Woolf. Love's Civil War has just been re-released in paperback.

|

1522. Reed, Henry. "Hardy's Secret Self-Portrait." Review of The Life of Thomas Hardy, by Florence Emily Hardy. Sunday Telegraph (London), 25 March 1962, 6.

Reed says this disguised autobiography is a "ramshackle work," but is still "packed with a miscellany of information not available elsewhere, and readers who care for Hardy will find it everywhere endearing, engaging, and full of his characteristic humour."

|

What makes for a best-selling memoir? Celebrity confessions. Confessions like Mackenzie Phillips reveals in her book, High on Arrival, that she had been involved in an incestuous relationship with her father. Such as Andre Agassi confessing that his trademark long hair was actually a wig and that he used crystal meth, in his forthcoming autobiography, Open.

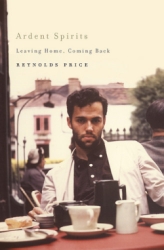

I confess, I don't actually know what bombshells Reynolds Price may drop in his recent memoir, Ardent Spirits: Leaving Home, Coming Back (New York: Scribner, 2009). I have my library's copy here, on my crowded coffee table. I haven't read it, yet. Not all of it. But I have found a pertinent piece of juicy gossip.

Reynolds Price has been a Professor of English at Duke University for fifty years, and is an award-winning author of fourteen novels. Ardent Spirits is his third memoir, covering his three years as a Rhodes Scholar at Merton College, Oxford, beginning in 1955, until after his return to North Carolina in 1958, when he begins his teaching and writing careers. Price has never written openly about his sexuality until this most recent volume, where he refers to himself (and others) as "queer."

While at Oxford, Mr. Price made the acquaintance of such literary luminaries as W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Cyril Connolly, and Helen Gardner—then a fellow at St. Hilda's College. Price attended Gardner's lectures on the metaphysical poets, and her seminar in textual editing, and eventually she would sponsor his thesis on Milton's use of the Chorus in Samson Agonistes.

This is where I get to the juicy part, the bombshell. In the mid-1930s, Henry Reed had been a student of Gardner's while he was doing his graduate studies at the University of Birmingham. Price writes:

Helen Gardner knew her subjects exhaustively and conveyed her mastery in lucid, but never condescending, lectures—one of the rarest of academic skills. She'd nonetheless been subjected to many of the disappointments of a brilliant woman in what was then distinctly a man's world. Stephen Spender would eventually tell me that he'd heard from W.H. Auden that, when she held a job at the University of Birmingham, Gardner fell in love with the poet Henry Reed. Reed, however, was queer; and Gardner's encounter with that reality led to a psychotic breakdown. In the absence of a good biography, I can't vouch for Auden's story; but it has a likely sound, especially since I slowly became aware of her reservations about many of her male colleagues at Oxford, and more than once I heard her cast strong aspersions at Auden and his friends. As her pupil, of course I was fascinated to hear of those possible early troubles in her life. [p. 43]

Wow. This is not the sort of literary footnote I usually get to post. Still, I'm inclined to say Mr. Price's rumor is simple hearsay—an exaggeration as a result of a game of Telephone among poets—considering that Reed sent Gardner a copy of Eliot's "East Coker" in the spring of 1940, and that Gardner, in 1942, credited Reed with a point relating to "The Dry Salvages" (see previously). That hardly sounds like the aftermath of an unrequited love affair and mental breakdown.

|

1521. Reed, Henry. "Leading a Dance." Review of Fokine: Memoirs of a Ballet Master, translated by Vitale Fokine. Sunday Telegraph (London), 26 November 1961, 6.

Reed finds Fokine's memoirs "very absorbing and intelligent."

|

This post is about as real as research gets. It's international! It's got everything—from old, primary source documents, to cell phone pics! Reed on, read on: