|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from December 2008

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

In scanning a full-text copy of Book Review Digest for 1946 at the Internet Archive, I noted several pieces of criticism by Henry Reed, including his rather famous review of Waugh's Brideshead Revisited for the New Statesman and Nation (23 June 1945, p. 408-409). Reed's review is often quoted by Waugh scholars as a piece of contemporary criticism, and was reprinted in Evelyn Waugh: The Critical Heritage (Martin Stannard, ed. London: Routledge, 1984).

NEW NOVELS Brideshead Revisited. By Evelyn Waugh. Chapman and Hall. 10s. 6d.

Household in Athens. By Glenway Wescott. Hamish Hamilton. 8s. 6d.

I Will be Good. By Hester W. Chapman. Secker and Warburg. 10s. 6d.

Serious implications have been present often enough in Mr. Evelyn Waugh's previous novels. The title of A Handful of Dust was significant; and certain excruciating moments in that book, as when the mother hears of her little boy's death, were threatening signs of a novelist whose powers were not easily to be ignored. Those powers find full expression in Brideshead Revisited, a novel flagrantly defective at times in theme and artistic sensibility, yet deeply moving in its theme and its design. It is as well to describe Waugh's faults at once; they recur constantly, both while one is reading him and while one is remembering him. They radiate almost wholly from an overpowering snobbishness: "How beautiful they are, the lordly ones," might well stand as an epigraph to Mr. Waugh's œuvre so far. A burden of respect for the peerage and for Eton, which those who belong to the former, or who hate been to the latter, seem able lightly to discard, weighs heavily upon him; and his satiric studies of the follies and cruelties of the posh have always been remarkable for the fact that their poshness has always seemed to the author more lovable than their silliness has seemed outrageous. It is a kind of snobbishness which finds one outlet in a special vulgarity of its own. There are several scenes in Brideshead Revisited where the narrator sets his own savoir faire against that of the lower characters—the scene in the Parisian restaurant with the colonial go-getter Rex, for example, or the pages satirising the transatlantic liner—and emerges as no less vulgar than his victims. It is as if a man should repeatedly point out to one that his bottom waistcoat-button is undone. This vulgarity goes very deep with Mr. Waugh; and it is not surprising that in embarking on his serious novel he should show an addiction to the purple.

The subjects of Brideshead Revisited are the inescapable watchfulness of God, and the contrast between the Christian (for Mr. Waugh, the Roman Catholic) sinner, and the other kind of sinner described in the cant term of our day as "pagan." Boldly, Mr. Waugh writes throughout from the point view of the pagan, which he, a convert to Roman Catholicism, has not forgotten; even more boldly he puts some of the most devout of Roman Catholicism among his least attractive characters. The book opens with a tale of romantic friendship at Oxford in the years following the first great war. Charles Ryder, the narrator, falls in love with Lord Sebastian Flyte, the beautiful son of Lord Marchmain; Marchmain himself, once a Catholic convert, is now an apostate; Sebastian is half-pagan. The Oxford passage, comic and romantic, is the most brilliant part of the book; nothing in the later part approaches it, save the last few pages of the story proper. The farce is of a high order; the picture of the narrator's father is a masterpiece of comedy; and the seeds of the later conflict are dextrously sown.

Sebastian is tormented by his mother, whom he cannot bear to be with. The mother is a mysterious and ambiguous figure, but not dissatisfying to the reader on that account. Sebastian's father has cut himself off from her and lives in Venice with a mistress. Like Sebastian, he flees from her, and it is perhaps not an over-interpretation to see here a suggestion that she represents some of the absolute exaction, difficult to face, of the Church. Symbolic or not, she is, in the story itself, patient, wonderful, cunning and unbearable; Sebastian cannot keep Ryder to himself and away from the family; and gradually he secedes from the relationship into drunkenness and vagabondage. Ten years later, Charles again meets Sebastian's sister, Julia, unhappily married to the barbarian Rex. The family charm works again, Charles falls in love with her, and is, in a curious phrase, "made free of her narrow loins" during a gale in mid-Atlantic. For two years their love survives happily; they are both about to be divorced in order to marry each other, when Julia feels "a twitch upon the thread"; she is reminded that she is living in a state of unchanging mortal sin, and cannot escape that consciousness; in the final pages, Charles is dismissed; we have already learned that Sebastian, far away in Morocco, has also felt the twitch upon the thread. The second part of the book falls far below the first; not only because for many pages we live in the dimensions of a gaudy novelette, enlivened, if at all, by the author's testiness at other people's bad taste, but because Julia is only a theme and not a person, whereas Sebastian has been both. Julia is alive only in her final speeches; and then simply because what she says is alive.

Underneath all the disfigurements, and never for long out of sight, there is in Brideshead Revisited a fine and brilliant book; its plan and a good deal of its execution are masterly, and it haunts one for days after one has read it. If one is reminded of François Mauriac it is not because Mr. Waugh's book is derivative, but for two other reasons. One remembers how much M. Mauriac can take for granted in his audience: Christian or agnostic, it knows what Catholicism is about. Mr. Waugh is in the far more difficult position of writing to an audience which in general is without that knowledge; he acquits himself convincingly, even to the pagan reader. Secondly, M. Mauriac reminds one of a lack in Mr. Waugh, for the great French novelist has sympathy with, and love for, the actual emotions of human beings. This sympathy and love are things no novelist can get along without; they are things which Mr. Waugh is still in the process of acquiring or reacquiring. A hard task; for they do not always survive religious conversion.

Household in Athens, Mr. Glenway Wescott's new book, is unusual among war-novels. Shock-tactics of technique, hysteria, over-loaded local colour, eager, unscrupulous cashing-in on the disasters of others: these are absent. It is not merely the intelligence and the watchful eye that have been engaged here. The heart is a dangerous necessity to the novelist; but it is, after all, his usual starting-point, however far away he gets from it. It is the first way of access which the author has to his characters. Mr. Wescott feels as deeply about his Greek family under the German occupation as the peace-time novelist feels about the creatures who build themselves up in his imagination and demand release. His four Greeks are thoroughly envisaged, the complexity of their plight, the slow, day-to-day horror, the mental dissolution and metamorphosis, the fantastic tricks played upon the mind bv physical decay, are desscribed with a realism of great calmness and strength. There is no local colour—a great relief. The Acropolis rises before us for a moment, but not for that purpose. There are no atrocities. It is a novel which explores its territory with great sincerity; it is a deliberately restricted territory, but there are moments when Mrs. Helianos's struggle with despair reaches out beyond the historical situation which provokes it. It is a profoundly moving book.

I Will be Good promises at first sight, and in its opening pages, to be a well-written, leisurely, escapist, comic novel; but into it one fails to escape. Nor is one meant to, though it might be possible to read the book as a romantic historical novel of immoral high-life in France in the eighteen-sixties, differing from others only by an unusual twist of fantasy. In point of fact, it has an almost Jamesian "idea" provoking it: a successful English lady novelist comes to live with a French family whom she well-meaningly, but insidiously and disastrously, persuades to behave like characters in one of her own romances. It is part of the great cleverness of the book that one is made to conjecture for oneself—and accurately, one believes—how the characters would have behaved if left to their real life. One knows, every time a wrong turning is taken, what the right alternative would have been. Between the amusing opening chapters and the beginning of the mischief there is an hiatus where one is out of step with the author's intention; as soon as this intention is clear the book is completely entertaining.Henry Reed

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

In November of 2006, Professor Jon Stallworthy gave a talk at the Poetry Trust's Aldeburgh Poetry Festival ( picture), entitled "Henry Reed: The One-Poem Poet?" The talk was, admittedly, a reworking of the introduction to Reed's Collected Poems (1991), in which Stallworthy refutes the idea that "Naming of Parts" will forever eclipse any other poetry Reed had attempted to write, and argues that Reed can finally, at "everlong last, take his rightful place at 'the starry feast'" ( Aubrey de Vere).

Stallworthy has a new book just out, Survivors' Songs: From Maldon to the Somme, a "series of poetic encounters with war." There are essays on Brooke, Sassoon, and Owen (Stallworthy has both written a biography, and edited the definitive edition of Owen's poems), and the the chapter, "Henry Reed and the Great Good Place": the revised text of Stallworthy's original introduction, which likely made up his 2006 talk at Aldeburgh.

Click the book icon to preview

this title in a new window.

In an introductory "Voice over" to the new book, Stallworthy defines his purpose in collecting these stories: "Good poets are survivors — even if, like Keats and Owen — they die at twenty-five."

I have spent many of the most rewarding hours of my life listening to the voices of absent friends — Thomas Hardy, William Yeats, Wilfred Owen, David Jones, Wystan Auden, Keith Douglas, and Old Uncle Tom Eliot and all — singing of human unsuccess

In a rapture of distress; and I think of the essays in this book as thank-you letters expressing gratitude in terms that, I hope, may lead other readers to listen to their voices and hear in them what I have heard. (p. x)

I am eager to get a copy of Survivors' Songs, and thanks to folks at Cambridge University Press and Amazon.co.uk, much of the book is available to be previewed (CUP even provides the handy book widget, seen above). Already I am noticing items I missed in previous versions of Reed's chapter: Reed and Ramsbotham took "civilian" lunches in Leighton Buzzard to get away from Bletchley; they briefly rented a house in Charlestown, Cornwall, in July, 1946; Reed's arrival in Verona in 1951 was heralded on the radio (he learned, later on, "with much delight"); there is a long poem, still in manuscript—possibly set during the American Civil War—alternately called "Matthew" or "In Black and White."

There is still much to be gleaned from the work set down by Professor Stallworthy, and readers have been given a second chance to really listen, and hear the voices that he has heard.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

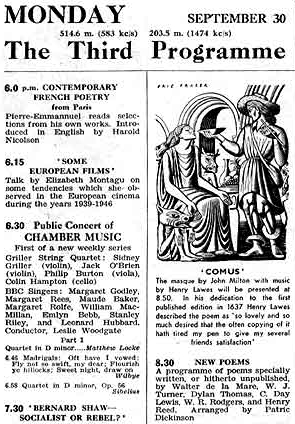

In September of 2006, the BBC launched a website to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the launch of the Third Programme (later, Radio 3), with specially-written articles, memories by staff and performers, letters from listeners (both "satisfied" and "disgusted"), and held celebratory broadcasts.

I remember being very excited when I found that the BBC had reproduced the September 27, 1946 issue of the Radio Times, which provided an introduction to the Third, its intentions, and programming.

If I had bothered, back in 2006, to look a little more closely, I would have noticed that Henry Reed was scheduled to take part in a reading of new poems by Walter de la Mare, W.J. Turner, Dylan Thomas, C. Day Lewis, and W.R. Rodgers, on September 30, 1946:

The "New Poems" program was arranged by the poet and translator Patric Dickinson, who worked for the BBC from 1942 to 1948. I'm not sure, but I believe Reed may have read his poem "The Forest," which was printed in the Listener on October 17, 1946, titled simply, "Sonnet." W.J. Turner, I'm sorry to say, died shortly after the broadcast, on November 18, 1946.

The entire 28-page issue of Radio Times is available from the BBC as a PDF document.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

In 1947, the academician D.J. Enright wrote a scathing indictment of the leading poetry magazine at the time, Poetry London. Founded in 1939 by Tambimuttu, Poetry London established the reputations of many poets of the 1940s, and famously published a "Poets in Uniform" number in 1941, which included the work of George Barker, G.S. Fraser, David Gascoyne, and Alun Lewis.

Born in 1920, Dennis Joseph Enright taught abroad in Egypt, Japan, Thailand, and Singapore for many years, before returning to Britain in 1970. Enright belonged to The Movement, a loose confederation of poets who were allied against the excessive romanticism of the earlier poetry of the 1930s and '40s, preferring more sober, rational efforts. Enright's article, "The Significance of Poetry London," appeared in the first issue of The Critic, in the spring of 1947. It is an attack on what Enright felt was the magazine's indiscriminate inclusiveness, or "anti-critical" editorial policies. The full text of the article is not available online, but we can piece the gist of Enright's arguments together from different sources:

Since 1939 (in February of which year the magazine Poetry London was inaugurated) something, it would seem, has happened to poetry. To suggest another aspect of the problem we might vary the proposition and say that since 1939 very little of any permanent value has happened in poetry. Never before have poets sprung up so thickly, never before has publication (given the right contacts) been so easy—but hardly ever before has accepted and recognized work shown such a striking uniformity of weakness. The question before us now is: Has the latter fact any connexion with the former facts? Can it, even, be a case of effect and causes? The Poetry of the Forties in Britain (1985), p. 277 Poetry is fast becoming a drug on the market; if an interesting poet emerges it is more than possible that his individual voice will be drowned in the general clamour; for every person who reads modern poetry without writing any, there are five who write poetry without ever reading any except their own and their friends'; the most influential verse magazine extant has consigned 'the critic' to an unpleasant death and openly disclaimed any principle other than catholicity; what little criticism is permitted has to remember that we are all poets, and poets ought to be one happy family, living together in a kind of pre-fabricated barn called an 'autonymous tradition.' Civil Humor: The Poetry of Gavin Ewart (2003), p. 277, 15n

And my favorite bit:

There really ought to be a society for the prevention of cruelty to metaphors. These Poetry London poets flog their overworked metaphors mercilessly, force them into the most unnatural postures, pour gallon upon gallon of obscure pathos into them, until they burst—into bathos.

This last comes from Blake Morrison's book, The Movement: English Poetry and Fiction of the 1950s (Oxford University Press, 1980, p. 34), which also provides this tantalizing quote: 'Enright exempted from his criticism only one Poetry London contributor, Henry Reed, whose "Lessons of the War" he admired because "too modest, or too wise, to attempt to deal directly with War"' [ sic].

I had previously scanned the wartime issues of Poetry London, looking for an appearance by Reed, but came up empty handed. I'm not sure if Morrison is correct in calling Reed a "contributor" to the magazine, or if he simply inferred it from Enright's praise. The university library's holdings are incomplete, and they have since removed the entire run to Rare Books for safekeeping.

Interestingly enough, in what appears to be a rebuttal in late 1947, Poetry London quotes Enright on Reed: 'The critic then proceeds to find Mr. Henry Reed's Lessons of the War "the best war poetry I have read."'

The Critic published only two issues before it was absorbed into Politics & Letters, making it rather difficult to find. In 1955, D.J. Enright edited (and contributed to) a collection of Movement poets, Poets of the 1950s, comprised of work by Kingsley Amis, Robert Conquest, Donald Davie, John Holloway, Elizabeth Jennings, Philip Larkin, and John Wain. Blake Morrison would later provide Enright's obituary for The Guardian, in 2003.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

Todd Swift of Eyewear reminds us that today, December 8th, is the anniversary of Henry Reed's death in 1986, at the age of 72.

It was about ten years ago that I made my first foray into Reed research, and looked him up in Contemporary Authors. That article pointed me to Reed's obituary in the London Times. At the time, the university's microforms collection, where they have the Times on microfilm, was still on the first floor, and not down in the windowless basement like it is, now. The microfilm is stored in these tall, vertical, overhead drawers, on top of the horizontal microfiche cabinets, all made of staggeringly heavy-gauge steel. I took out the box for the first half of December, 1986, carefully wound the film into the machine (following the diagram, always follow the little diagram), and spooled through almost the entire reel to get to December, and there it was: " MR HENRY REED" (.pdf). And it wasn't until years later that I would go back to very same reel of microfilm, looking for details on Reed's funeral (also .pdf).

Reed had suffered from complaints of the chest all his life, pneumonia and its complications, but perhaps Alan Jenkins summed up best the last years of Reed's life: '[P]erfectionism, failing eyesight, alcohol and a staple diet of Complan...[.]' Funeral services were held at Golders Green Crematorium and Mausoleum on December 16th, 1986, at 2:30 pm.

I also have Reed's article from the Annual Obituary 1986, edited by Patricia Burgess (London: St. James Press). It's fairly thorough, but compiled from Reed's entries in Contemporary Authors and the World Authors series, it inherits all of their flaws (like perpetuating the notion that Taylor's Anger and After (1962) contains anything more than a passing mention of Reed in its introduction).

Reed is not entirely forgotten, "Naming of Parts" has ensured his immortality, and he will continue to turn up in unlikely places. His translations of Montale's Mottetti were published just this year. That deserves a post of its own.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

Henry Reed reviewed Edwin Honig's biography of Federico García Lorca for the December, 1945 New English Review. Unfortunately, as you can tell from his opening paragraph, Reed was painfully discouraged with the book: 'very badly written,' 'overburdened with detail,' 'hard going for the reader,' and 'exhausting and baffling' are not the least of his disappointments, and one wonders why he bothered to read the entire thing. Such are the wages of the literary critic.

Garcia Lorca. By Edwin Honig. Poetry, London. 7s. 6d.

Federico García Lorca was assassinated by soldiers of General Franco's army shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. There was no excuse for the crime, and none has ever been offered. Lorca's only claim to offence is that he was a poet admired by intellectuals and loved by the general public. He had no violent political allegiances, and the fact that he had expressed no warmth of feeling for the Falange could not, even by the Falangists themselves, be regarded as an eccentricity. He has become a symbol of what suffers under the guilty self-righteousness of Fascism, and it is right that he should remain so. At the same time it is possible to wonder if his tragedy is not being overplayed, and if we are not self-indulgently identifying ourselves rather often with the poet and his deplorable fate. Mr. Edwin Honig is aware of these possibilities. His study of Lorca is very badly written; it is overburdened with detail; his potted history of Lorca's literary antecedents is hard going for the reader; his analysis of the action of Lorca's early play Asi Que Pasen Cinco Años [When Five Years Pass] must rank among the most exhausting and baffling pieces of expository criticism ever written; but at all events he does endeavour to remain alive to the dangers of martyrolatry and untempered prose.

It must therefore seem ungrateful to suggest that at the moment Mr. Honig is yet another of those critics who insist on getting in the way. The works by which we could most fairly be expected to judge Lorca have not yet been published in translation in this country, and so far all we have is a small number of selected lyrics and his remarkable Lament for Ignacio Sânchez Mejías (we still for some reason try in this country to to be outraged by bullfighting). These have been accompanied by a mass of eulogy; it has even been suggested that as a poet Lorca is comparable in importance with Eliot, Rilke, and Yeats. To be a poet on their levels, and to be of interest outside your own country, you must have a quality of subject-matter, of things said, which is at least moderately apprehensible in translation. Rilke has this; and so far as we can yet tell, Lorca has not.

Mr. Honig says of him in his concluding chapter: "His drama celebrates the life of instinct; which is to say, it does not come bearing a message. It comes in the ancient spirit of the magician and soothsayer—to astound, to entertain, and to mystify; it also comes in the spirit of the jongleur, to invent a world and people with whose pathetically valorous lives the audience is quick to identify itself." Mr. Honig appears to discern no limitations in this, and like many critics he seems to over-value the element of popular song in Lorca. But this fact seems as much a drawback as an advantage, so far as one may dimply see. There is no inherent advantage in staying in the ballad-period of your literary history. Lorca was a pianist and composer; and a practical knowledge of music may be of great help to a poet. But Spanish music, as "vital", impressive, and immediately attractive as any music, is at the same time extremely limited in character. (Of all prominent contemporary composers, de Falla is the least profound.) Few readers can fail to be delighted by the flashing succession of images in Lorca's poetry and by their daring dérèglement; but it is idle to pretend that it is more than a minor form of poetry.

With Lorca's dramas it is doubtless a different matter. But hitherto, for the English reader, criticism has preceded demonstration. Mr. Honig's book is one more preliminary announcement; he gives us detailed accounts of the plays, including the puppet and surrealist plays, and like Señor Barea a year ago he piques our curiousity about Bodas de Sangre [Blood Wedding] and Yerma; but he has not the acute critical power which will sometimes convince without a full text. Above all, Mr. Honig has little new knowledge about the poet himself to give us; it is surely rather tantalising to hint at a major unhappiness of a personal kind if you are unable to give any details of it; nor does he offer any suggestions as to why the theme of two of Lorca's principal dramatic works is sexual sterility, though no thoughtful reader can avoid being impressed by this fact. It is discouraging to record that as a whole the book really adds very little to the impression given by Señor Barea's sympathetic and charming drawing of Lorca in the nude.Henry Reed I will have to stop by the main library this evening, and poke about the Lorca aisle, and see if I might turn up Barea's 'sympathetic and charming drawing of Lorca'.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

Henry Reed graduated from the University of Birmingham in 1936 at the age of 22, with a Master of Arts degree. At the time, he was the university's youngest MA.

Reed's (147-page) thesis was on " The Early Life and Works of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1878" (library catalog), a copy of which now resides in the Thomas Hardy Collection of the Dorchester Reference Library, Dorset:

Dorchester's Hardy Collection contains 'nearly 1,000 theses for higher degrees in typescript or microform,' as well as critical articles from various literary journals.

It would seem likely that the University of Birmingham still has a copy of Reed's thesis, but if they do, they don't seem to have cataloged it.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

Just in time for the holidays, Oxford is reissuing (for the second time) their Oxford Book of War Poetry, edited by Jon Stallworthy (who also edited Reed's Collected Poems). The anthology contains Reed's original three Lessons of the War poems: "Naming of Parts," "Judging Distances," and "Unarmed Combat."

D.J.R. Bruckner, in the New York Times, had this to say about the Oxford War Poetry, first published in 1984:

Mr. Stallworthy comes well prepared to write about that breed. His biography of Wilfrid Owen swept the field of prizes when it appeared; he is the definitive editor of Owen's poems and his knowledge of war literature is wide. In his introduction to this anthology he traces the lineage of World War I poets to the 18th-century English public school, its curriculum chock full of ancient heroic poetry which upper-class youth took as personal inspiration. By 1918 the ideal had died with the class in the in the trenches. The emotional power of the poems written by the best of the group comes not only from their recognition of the degradation and hopelessness of soldiers, but from a feeling they were turning their backs on their upbringing. They would never again believe with James Thomson that 'guardian angels' sang the refrain of his hymn, 'Rule, Britannia!' ("No More Famous Victories," February 24, 1985, p. 340)

Stallworthy also talks at length about war poetry in the documentary Voices in Wartime ( transcripts of interviews). Here's Oxford's catalog page for the second reissue paperback.

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|