Wilfrid Mellers was a critic, composer, and in 1964, founder of the

Department of Music at the University of York. Professor Mellers is world-renowned for his enthusiastic love of all music, but especially for his embrace of folk, jazz, and pop. During his lifetime he produced a flood of books, articles, and original compositions, and was a respected pioneer in the study and teaching of music.

During the 1930s and '40s, while he was a supervisor in English at Downing College, Cambridge, Mellers was writing literary and musical criticism, most notably for the journal

Scrutiny (

Music & Vision article). One review he produced, notably for us, was for Henry Reed's debut collection of poems,

A Map of Verona. The piece appears in the July, 1946 issue of the

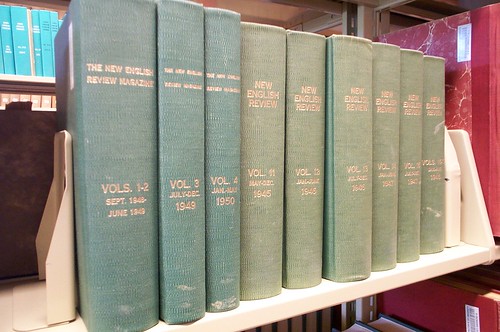

New English Review. Over the past weekend, I popped over to the

James G. Leyburn Library at Washington & Lee University to have a peek:

I was surprised to find not simply the blurb I had expected, but a lengthy review in which Mellers perceives the influence of Eliot on Reed, and Auden's influence on

Geoffrey Grigson. From "

Some Recent Poetry" (.pdf), by W.H. Mellers:

It is this search for formalisation, whether in slight or more difficult work that I find impressive in Reed's poetry. It is true that so far there is a certain limitation of emotional range about his characteristic movement, that the short poems are the more successful, and that the longer free-verse monologues evoke a comparison with Mr. Eliot's mature economy in this manner which no contemporary verse could live up to (even such sober and dignified verse as the vision of the dancers in "The Place and the Person" appears almost garrulous in so far as it suggests a relation to the "Dantesque" passage in "Little Gidding"). But Mr. Reed is none the less a poet and not a verse-maker; one awaits his next volume with lively anticipation.

(Mellers was, apparently, a firm proponent of both

italics and a liberal sprinkling of "quotation marks".)

Reed's 'next volume' never appeared, disappointingly (unless you count the five collected

Lessons of the War, in 1970), but I have happily added

Meller's review to the critical section of The Poetry of Henry Reed—the first major addition to the site in over a year—reviving hope that there are still forgotten book reviews out there, hiding in unvisited libraries, waiting to be rediscovered and reread.

Wilfrid Howard Mellers

died on May 16, 2008 (

Times obituary), in Scrayingham, North Yorkshire, at the age of 94.