So, the site experienced a horrible breakdown owing to an upgrade to PHP5 on my hosted server. All links were leading to the main page, and for who knows how long? Hilarious. I had to track down all my calls to get variables sent through the URL on all the page templates, and update them to the correct $_GET['$var'] format (or, in an SQL query, '$_GET[$var]'). That's what I get for not using WordPress or another supported service.

A few things may still not be working (comments, for instance, and will I be able to post this update? I think all my calls to post are properly formatted $_POST['$var']), but at least you can navigate the site!

Update: Aha! I could post, but not edit. Fixed fixed.

|

Puts and Gets

Two Short ReviewsMuch to my surprise, dragging the seemingly bottomless, boundless ocean of Google Book Search continues to net contemporary criticism of Reed's A Map of Verona: Poems, published in March of 1946. The two most recent catches are short critiques found schooling amidst and amongst much larger book review sections in the magazines Britain To-day and John O'London's Weekly.

The latter was the first to appear, in June 1946: "Poets Worth Praising," by Richard Church, author of the World War I poem, "Mud" ('Twenty years ago / My generation learned / To be afraid of mud. / We watched its vileness grow, / Deeper and deeper churned / From earth, spirit, and blood'). In addition to Reed's book, Church reviews The Golden Year of Fan Cheng-Ta by Gerald Bullet, Talking Bronco by Roy Campbell, London Saga by Stowers Johnson, The Voyage by Edwin Muir, and Vita Sackville-West's The Garden. While he devotes little more than three paragraphs to A Map of Verona, Church's evaluation of Reed is unequivocally positive:  He appears as a man of wry, almost sly, humour, endowed with a shrewd critical mind that gives his first work a matter-of-factness wholly acceptable to the fastidious reader's palate. In that technique of dry statement, sometimes almost categorical, you discover a highly individual poetic faculty. It gives his work a stillness that is startling, like the skies in Dali's queer pictures. A few months later "A Poet of Sensibility" appears, in the October, 1946 issue of Britain To-day. I had brief hopes that this review had been penned by the pre-eminent critic and scholar, Kathleen Raine (Raine's article "English Poetry Since 1939" appears in this issue), but it turned out to have been written by an obscure poet and critic, A.C. Boyd. Boyd is quick to mention Reed's debt to Eliot, but doesn't find Reed slavish, as many other critics do:  We know of Mr. Reed's admiration for T.S. Eliot and Edith Sitwell, but he is no slavish imitator of either of them, indeed his talent is unusually original and spontaneous. For sheer invention we can turn to Lessons of the War, in which the poet has reproduced the gabble of the sergeant-instructor on Unarmed Combat and so forth and shot it through with most sensitive observations and a lightning play of wit—a seriocomic fantasia which is a joy to meet. There is passing mention of "Chard Whitlow," and praise for both the early poems as well as the Antigone monologues, but Boyd concludes by extolling Reed's series of four poems on the Arthurian legend of Tristan and Iseult: The dramatic monologue, the recounted allegory, here passion, irony, and a critical intelligence and boundless curiosity to explore experience can find full play. But in his use of what one might call the inflected 'voice' he is never extravagantly rhetorical, in fact he speaks often enough in a near-prose murmur; he can be deliberately ingenuous or rise to a tragic intensity all in the same poem. He has equal command of the long, modulated sentence as of the more limpid, short line. Everything in this small book is of interest, but the haunting beauty and sweep of imagination of the Tintagel poems is something to be thankful for in these days of austerity. Boyd himself is obscure enough that he doesn't even rate his own Wikipedia page. Almost all I can discover about him comes from a 1939 issue of Denys Kilham Roberts' Penguin Parade, which features Boyd's poem, "Death of a Poet" ("Cover the frost-bitten features, the twisted hand; / Straighten the shattered limbs, / And the eyes, icicled, that could not weep"). The contributors' notes state he was born in 1902, and that he was raised in India, where his father was a judge. He was educated at University College, London, and held a diploma in librarianship. According to A Companion to Pablo Neruda (2008, p. 164), Boyd and his architect brother Andrew were the first to translate the Chilean poet's works into English, Andrew having befriended Neruda in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), around 1936.

Happy 5th BirthdayThis month marks the fifth birthday—anniversary, really—of the Reeding Lessons research blog. The flagship post was in April, 2005, and since then I've managed 350 entries, give or take. That works out to almost six posts per month, if I divided correctly, and is a surprising average, to tell the truth.

Since I started, the bibliography (pictured above) has slowly and steadily grown; I've visited a dozen libraries (including the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution's horticulture library), and uncovered at least half that many reviews of Reed's work; I've been privy to 50-year-old jokes; I've held rare library treasures in my own hands, found over 60 locations that Henry Reed personally visited, and been shown his home in Birmingham; I've seen visits from professors, librarians, poets, students, artists, archivists, and even the likes of Ken Russell; and, most importantly, the site has helped three scholars (that I know of) publish critical works on Reed and his life and work. Which was the whole idea in the first place. Many items posted here wouldn't have been possible without the occasional prodding from the occasional (or occasionally regular) Reeder, so wish yourselves a happy happy, too! Thank you.

Plum DeliciousA couple of years back, I started using Magnolia to manage my bookmarks for links to Reed-related webpages: news items, library collections, biographies of other poets and writers. Since then, I had created over two hundred bookmarks, with descriptions and associated tags.

You probably hadn't heard, but on January 30th of this year, Magnolia suffered a catastrophic loss of user data, and backups. "This is just to say," goes William Carlos Williams, "that I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast." To their credit, the site has since provided several data-recovery tools, one of which managed to find cached examples of 197 of my bookmarks. The most recent items are still Missing in Action, as it were. This morning I imported my recovered bookmarks into Delicious. You can see the new linkroll in the lower → right-hand ↓ sidebar of this page, under the "Marginalia" heading. I still need to tweak the styles, but it works!

Cited in British and Irish PoetsImagine my surprise, poking about for Reed references in Google Book Search, when what should I come across? Our very own website, The Poetry of Henry Reed, cited as a source in British and Irish Poets: A Biographical Dictionary, 449-2006, edited by William Stewart (2007).

From Amazon.com's product description: "From John Abbot to Benjamin Zephaniah, this reference book contains information on 1,270 poets from England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. Writing over a 1,500 year period, the featured poets are representative of periods from the Old English era to the Post-Modern age." I know the site has been used to produce at least two other scholarly articles, but this is the first time I've actually seen it cited!

Echoes of Eliot and AudenWilfrid Mellers was a critic, composer, and in 1964, founder of the Department of Music at the University of York. Professor Mellers is world-renowned for his enthusiastic love of all music, but especially for his embrace of folk, jazz, and pop. During his lifetime he produced a flood of books, articles, and original compositions, and was a respected pioneer in the study and teaching of music.

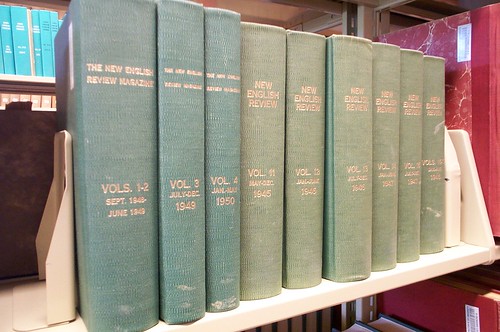

During the 1930s and '40s, while he was a supervisor in English at Downing College, Cambridge, Mellers was writing literary and musical criticism, most notably for the journal Scrutiny (Music & Vision article). One review he produced, notably for us, was for Henry Reed's debut collection of poems, A Map of Verona. The piece appears in the July, 1946 issue of the New English Review. Over the past weekend, I popped over to the James G. Leyburn Library at Washington & Lee University to have a peek: I was surprised to find not simply the blurb I had expected, but a lengthy review in which Mellers perceives the influence of Eliot on Reed, and Auden's influence on Geoffrey Grigson. From "Some Recent Poetry" (.pdf), by W.H. Mellers: It is this search for formalisation, whether in slight or more difficult work that I find impressive in Reed's poetry. It is true that so far there is a certain limitation of emotional range about his characteristic movement, that the short poems are the more successful, and that the longer free-verse monologues evoke a comparison with Mr. Eliot's mature economy in this manner which no contemporary verse could live up to (even such sober and dignified verse as the vision of the dancers in "The Place and the Person" appears almost garrulous in so far as it suggests a relation to the "Dantesque" passage in "Little Gidding"). But Mr. Reed is none the less a poet and not a verse-maker; one awaits his next volume with lively anticipation. (Mellers was, apparently, a firm proponent of both italics and a liberal sprinkling of "quotation marks".) Reed's 'next volume' never appeared, disappointingly (unless you count the five collected Lessons of the War, in 1970), but I have happily added Meller's review to the critical section of The Poetry of Henry Reed—the first major addition to the site in over a year—reviving hope that there are still forgotten book reviews out there, hiding in unvisited libraries, waiting to be rediscovered and reread. Wilfrid Howard Mellers died on May 16, 2008 (Times obituary), in Scrayingham, North Yorkshire, at the age of 94.

Henry Reed Google MapPlease, keep in mind that this is a work in progress, extremely rough. I've been toying around with it since last fall, when I was trying to find the original location of Bowen's Court (#15, below). Allow me to present The Life and Times of Henry Reed: A Google Map (βeta). Click this image to go the map page, and then you can follow the labeled locations, zoom in and out, and switch between road map and satellite views. And of course, remember, "Maps are of time, not place."

I used one of the Google Maps API Demos to kludge the map into The Poetry of Henry Reed pages. It should be relatively browser-friendly, though I've really only test-driven it in Firefox. If you have problems, try looking at my original Henry Reed map in Google. I've already received one comment which allowed me to amend my timeline of Reed's life, and I'm updating the map on almost a daily basis.

Upgrade, BackslideAs promised (or should I say, forewarned), my hosting service migrated from php4 to php5, today. This caused me no end of frustration, as it basically meant none of my pages were being recognized (and therefore, not displayed) due to my .htaccess settings. If anything, you would have seen an error message, or gotten a peek at my raw code. I ended up having to password the whole site for awhile. The magic words, I finally discovered, are:

AddType application/x-httpd-php5 .php .htmlIf anyone notices anything particularly wonky on the blog, or if you wandered in here from the contact page on The Poetry of Henry Reed because you noticed something wonky over there (and I mean Willy Wonka wonky), please drop me a line? Thank you!

Travis Bickle DietI'd like to start implementing a strict regimen of diet, exercise, and meditation, based on Robert DeNiro's "Gotta get in shape" monologue from Taxi Driver. The Travis Bickle diet plan (YouTube):

I gotta get in shape. Too much sitting has ruined my body. Too much abuse has gone on for too long. From now on there will be fifty push ups each morning, fifty pull ups. There will be no more pills, no more bad food, no more destroyers of my body. From now on will be total organization. Without all the Scorsese movie violence, of course. Travis had plenty of motivation, but lacked a suitably constructive outlet. When I'm finished, I'll push over my television set, rise from the ashes of my abusive disorganization, and someone will offer me my own late night infomercial, so I can help others achieve the same results. This weekend, I'm going to swap out the limping harddrive in my laptop, which I've been nursing along for almost three whole months. I'm backing up data as I write this. Docs. Mail. Bookmarks. Hopefully, a clean slate will restore my levels of productivity and enthusiasm. Cross your fingers, wish me luck. Organizize!

Up to SpeedJust a few updates. The bibliography is looking fairly smart now, in its Noguchi-style open-shelf filing, wouldn't you agree? (Compare with my last filing update, Feb. 2006.)

I actually managed to rid myself of one of the file boxes seen piled on the right. Plastic albatrosses. I think I need to buy a couple of more stackable cubes, too, when I have the spare change. They're cheap, but shipping's a killer. Also, I've been steadily finishing bringing the Henry Reed pages up to date, even as I'm considering redesigning and upgrading to version 3.0. The site's getting a little tired, and starting to show its age, don't you think? Most recently, I edited Roger Savage's lengthy chapter from British Radio Drama, "The Radio Plays of Henry Reed," adding page numbers and the all-important appendix, which lists almost all of Reed's radio dramas and their dates of broadcast. Currently, I'm still waiting for Amazon.com to ship me two copies of the new, paperback edition of the Collected Poems. Their estimated date of shipping is not until October 11th!

Under SiegeSidney Keyes was a youthful poet killed before he had time to register the impact of warfare; Alun Lewis registered the deadening effect of regimentation and the stimulus of travel, but left no record of the military action it seems it was his destiny to seek. Douglas sought action, found it, recorded it and his fear of its consequences, before he too died. Roy Fuller was excluded by circumstance from action and was able, literally from a distance, to mark the changes that wartime forced on society and the enclosed microcosm of the services. Each is an individual experience, and it is because of the quality of their work that they are accepted as the chief poets of the Second World War. But it is appropriate that none of them wrote the poem of the Second World War. That was written by Henry Reed. Thus begins Robert Hewison's analysis of Reed's Lessons of the War poems, in the book Under Siege: Literary Life in London, 1939-1945 (Oxford, 1977). Interestingly, Hewison treats the whole sequence as a single work, mentioning, but not lingering on (or even quoting from), "Naming of Parts."  Hewison prefers instead to look at "Judging Distances" at some length. 'In this case the landscape has to be interpreted in formal terms; the distance cannot be judged emotionally, the territory must be seen as a map. But in the trainee-soldier the surviving civilian persists in reading the topography with his own eyes...' (p. 139). Though Hewison has chosen a slightly less famous poem, the resulting commentary is familiar: 'Individuality has to be sacrificed to the needs of the military machine, the landscape reduced to the terms of tactical necessity, but some small item of personality could be retained — the observing eye of the poet' (p. 140). He then turns to "Unarmed Combat," the last of Reed's Lessons published during wartime, concluding, 'Henry Reed achieves a rare fusion between soldier and poet of the Second World War...' (p. 140).

Love, Release, the RevelationI recently added, and failed to note here, Alan Jenkins' 1991 Independent review of Reed's Collected Poems, "In Other Men's Shadows." Jenkins notes the poet's debts to Hardy, Auden, and MacNeice (Reed 'pre-echoes' The Movement poets), but points out

[w]hat is Reed's and Reed's alone is a tonality, an emotional palette, a special feeling for romantic potentiality, the moment before something tremendous happens or after it has receded. The something tremendous — love, release, the revelation of transcendent beauty, all of these at once.... 'Properly,' Jenkins says, the posthumous collection 'rescues Reed from the two-poem limbo to which the anthologies... have consigned him.' Also very recently, I discovered a lovely summary of Reed's poetic influence and influences, in The New Guide to Modern World Literature, by Martin Seymour-Smith (New York: Peter Bedrick, 1985): Henry Reed (1914) has published only one collection of poems, A Map of Verona (1947), but this is widely read — it remained in print for a quarter of a century. There are a few good uncollected poems. He has earned his living as a translator and writer of radio scripts — including the famous 'Hilda Tablet' series. Reed has written several distinctly different kinds of poem: the metaphysical, influenced above all by Marvell; a narrative, contemplative poetry influenced by Eliot (q.v.); parody — as in 'Chard Whitlow', which was Eliot's own favourite parody of himself; a narrative poem influenced not by Eliot but by Hardy (q.v.) — such as 'The Auction Sale'. Reed's justly famous 'Lessons of the War' sequence is in his metaphysical vein, exploiting double entendre to its limit, varying the tone from the wistful to the broadly comic (as in the third poem of the sequence). The less well known 'The Auction Sale' handles narrative as well as it can be handled in this age. Reed is a poet of greater range than is usually recognized; only his Eliotian contemplative poetry really fails to come off, and even this is eloquent and rhythmically interesting.That single paragraph comes the closest I've seen to placing Reed solidly in any school of poetry, even though it leaves him straddling Hardy's Naturalism, The Romantics, and the Moderns. Additionally, I turned up a very nice exploration of the 'military/poetic problem' in "Judging Distances," in Robert Hewison's Under Siege: Literary Life in London, 1939-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), which I hope to be able to post soon. Stay tuned!

Stand CorrectedA post I made a while back about a (lost) poem Reed wrote parodying the Northwest School of poetry receives a correction from a distinguished visitor.

KERNEL_STACK_INPAGE_ERRORIf your hard drive has to give up the ghost, I guess this is probably the best way.

Two weekends ago, I was sleepily browsing the internet during morning coffee, when my laptop literally went "Kaflooie!" and started throwing Blue Screen of Death after Blue Screen of Death. It wouldn't boot at all at first, but finally started up again, albeit running impossibly slow, and only for ten minutes at a time. I did get one excellent streak where it stayed alive for more than an hour, and I managed to copy my email and all my Reed-related documents to CD. I had a recent backup, but I wanted to be absolutely sure I got everything. With a new hard drive installed, I spent this weekend updating Windows, updating Windows, downloading software, updating Windows, and reconfiguring my wireless. I should be happily posting again, soon!

Flowers and WarSeveral weekends ago I made a short excursion up to the state capital, to visit the Richmond Public Library. It was a lazy, rainy Sunday, and I needed, of all things, a 19th-century book on flowers.

The book was the Reverend Hilderic Friend's Flowers and Flower Lore (1883), and I was startled to find that it was not on the shelf. Up and down the folklore section I scanned. A word to the wise scholar: it never hurts to phone ahead. Luckily, a librarian flew to my rescue, advising that their older texts are kept in closed stacks, downstairs in the basement. Whew! I had Friend's beautiful, leather-bound, two-volume set in my hands, momentarily. In the end, I found that they didn't even contain exactly what I was looking for. Such are the perils of blind librarying. I consoled myself by browsing the stacks for poetry, discovering that my Dewey Decimals have become almost irreparably rusty. Poetry: 811, yes. English poetry? 821. Oh. They had several anthologies which I had indexed but never seen: notably, Dylan Thomas's Choice (Maud and Davies, eds. New York: New Directions, 1963). Deep into my Ziploc bag of dimes I dipped, to feed the ravenous Xerox machines. The real boon was a book I had never heard of or seen: War Poetry: An Anthology, edited, and with an introduction and commentaries, by D.L. Jones (1968). This evening, I added Jones' commentary on the Lessons of the War poems to the website. It also happened to be the last day of the Friends of the Library booksale, and from the pillaged remnants I managed to scavenge a small paperback of English translations of the poetry of Leopardi. They wanted 50¢, but I gave them a buck, and told 'em to keep the change.

MagnoliaizedI have a folder in my Firefox bookmarks just for Henry Reed-related webpages. Many of these were imported from IE's favorites when I "upgraded" browsers. Most of them are throwaway hits from brute-force keyword attacks in major search engines: '"henry reed" bbc', '"henry reed" translation', and the like.

Unfortunately, once your bookmark folder exceeds the height of your browser, it becomes less and less managable, until it finally becomes impossible to find anything at all. Especially if you're just lazily dumping in webpages with "Bookmark This Page...", and not bothering to edit the titles or descriptions. For shame. So, onto social bookmarking! I exported my bookmarks to html, and imported them to Ma.gnolia, and spent an hour or so deleting the extraneous, non-Henry, links. Zip zop. What remains needs some pruning and a lot of editing, but here you have them: my Henry Reed bookmarks (with tags!).

Where Are the War Poets?The question everyone was asking in the late 1930s and early 1940s was "Where are the war poets?" There was no Brooke, no Sassoon, no Owen. John Lehmann asked it. Wilfrid Gibson asked it. Robert Graves asked. C. Day Lewis asked, and answered:

They who in folly or mere greedRather, I prefer E.M. Forster, who frankly declared, "1939 was not a year in which to start a literary career." An addition to the Criticism pages: an excerpt on Reed from Linda M. Shires' British Poetry of the Second World War (New York: St. Martin's, 1985). Shires has written one of my favorite lines in summarizing "Naming of Parts": 'The speakers are soldiers, yet the most important feelings in Reed's poem are not spoken, as though the private man has no voice worth hearing compared with man-as-soldier' (p. 82). It's a fine piece, which I had actually acquired over a year ago but failed to transcribe, time lost to obsessive tinkering with the database, trying to get the bibliography to sort properly. One thing is bothering me, however, and that's the epigraph to the chapter entitled "Where Are the War Poets?" Shires has credited Reed with the line "To fight without hope is to fight without grace." At first, I thought this was part of the Lessons of the War series — "Unarmed Combat" perhaps — or some draft I had seen but not taken sufficient note of. To fight without hope is to fight without grace. Is it from an article in The Listener? A radio talk? I can't find that line, not anywhere.

One Thousandth EntryAnd the winner is... David Jones, ladies and gentlemen!

It was two years ago this month that I first wrote the code which enabled me to display the Reed bibliography on the web. The code is a heinous mish-mosh of ifelse loops, created to display records in some semblance of order by author, title and date. As it has grown, the database has become less and less useful, at least to those unschooled in the esoteric skill of Ctrl>F or Edit>Find in This Page. Tonight, I am celebrating the input of the 1,000th record into the bibliography. Entries from the bibliography, you may have observed, are framed in gray boxes between posts in this blog. If you watch closely, you'll be able to see them roll over from nine hundred ninety-nine to one thousand, just like watching an odometer. I'm celebrating this achievement with a lovely red wine from the vineyards of Spain, and after two glasses I am absolutely in no shape for data entry. (In the interest of full disclosure, I should point out that, while this is the 1,000th entry, it is not the 1,000th record. I have deleted about fifty-odd duplications or books which eventually turned out to not actually mention Reed. So it's really the 947th record.) This evening, I went to a lecture on ancient libraries, given by Professor George W. Houston. The lecture room was standing-room only: apparently, the Roman Civilizations professor was offering extra credit for attending. So, squashed between row upon row of sophomores, I sat and listened about Herculaneum's Villa of the Papyri, Oxyrhynchus' town dump, and the library in the Temple of Trajan. Professor Houston's presentation was billed as "A User's Guide" to libraries in the Roman world. He has been attempting to discover how private and public libraries functioned in regard to their users in the ancient world, through scant evidence left in fragments of papyrus scrolls and codices. On the handout provided, Houston provided a translation of an inscription found in the Agora of Athens, pertaining to the Library of Pantainos (2nd-century, A.D.): No book shall be taken out, for we have sworn an oath. Open from the first hour to the sixth.Those, the Professor stressed, are the only official library regulations surviving from the ancient world. After the lecture, I actually popped over to the library, since they had emailed me earlier that the book I had requested from offsite storage was ready and waiting. The book was Epoch and Artist: Selected Writings by David Jones (Grisewood, ed., 1959). It seems all the books I need are in offsite storage, these days. I opened it with no expectation of finding anything related to Reed, and after glancing at the title page and copyright, turned to the index. There it was: an entry for "Reed, Henry, 278-79." The indicated pages turned out to be a reprint of a letter to the editor Jones wrote to The Listener in 1953, in response to Reed's essay, "If and Perhaps and But." "If and Perhaps and But" is a review of T.S. Eliot's critical prose in which Reed argues that, sometime between the early 1920s and 1950s, "something happened whereby it is now possible for the poet to implement a 'formal artistic discipline derived from the outside'" (Jones quoting Reed). Mr. Jones goes on for three paragraphs requesting an elaboration because, apparently, he cannot for the life of him figure out what "something" Reed is talking about. Neither can I, for that matter, as I have yet to track down a copy of that particular Listener. Regardless, David Jones has the distinction of being the 1,000th record entered into the bibliography. And the 1,001st, too, since thoroughness dictates that I must cite the original letter as well as the reprint! Thank you, Mr. Jones!

Leaf a CommentAfter receiving several emails, but no comment spam whatsoever, I suspected something was brok. En. Why didn't some good web Samaritan mention it?

Commenting should be enabled, fixed, and working. Now, if I could just figure out how to sort my categories by date, then alphabetically.

The Safety-CatchFor over two years now, since the last time I overhauled the look and feel of the Henry Reed pages, I've been caught in a struggle between design and accessibility, form versus function. The problem, in a nutshell, is that many visitors could not recognize the only clickable button on the site as an actual, clickable button.

Since the site was for the author of the poem "Naming of Parts," I tried to have a theme involving various rifle parts in silhouette: an image map on the homepage, random images on the content pages, and a "flickable" safety-catch to use to send in a search query: But this proved confusing for many users. Last month, for example, out of a total of 321 search queries run, no fewer than 72 were for the word "Search," which appears by default in the search box as an identifier. Folks were just clicking on the little safety-catch to see what it would do, and then flipping and digging through the search results and landing on whatever looked interesting. But since the word "search" appears on every page, the results were more or less random (except that the Search page was ranked highest), and a lot of people just ended up choosing an item from the header navigation row. I was also seeing far too many blank queries: people clinking in the text field and then sending an empty box home with the safety-catch. I really didn't want to give up the safety-catch button. Sure, it's gimmicky. But it tied the whole theme together. Flick the safety-catch. Never letting anyone see any of them using their finger. But an excess of between 50 and 100 users a month, failing to use one of the simplest interfaces on the site? That's just too many. So I finally broke down, let go of my stubborn, tenacious fixation on design, and let myself gently down into the icy current of the lowest common denominator: A button.

WhaddyacallitThere's still a lot to do around here before going live with these pages. I'm still struggling with if-do-while-else loops in php, and the template's not really quite what I would like. I'm also in the process of copying over the relevant posts from the old blog, and some from the defunct "News" page (the old posts made for tasty test data). All posts from before today's date originally existed somewhere else.

More importantly, I have no idea what to call the thing. It's like getting a band together: the best part is dreaming up a cool name. The choices so far:

Newest AdditionsAdded a new audio file of Robert Pinsky reading "Naming of Parts," an insightful letter into Reed's time in Seattle, and an equally revealing review of the Collected Poems.

Poem Pages FinishedThe twelve Henry Reed poems reproduced here have all been converted to the new style. Some long-existing typos have been caught, and conversion to all-British spelling is being considered. The remaining pages and content continue to be updated. A new interactive bibliography should be ready soon, drawing on a database of sources concerning Reed and his work!

Facelift for Henry ReedThe site is currently undergoing significant changes in layout, color scheme, and functionality. Rest assured, however, the content is still all here (and then some)! If things go according to plan, the original pages will co-exist alongside the new until they are replaced, but the transition may seem a bit jarring to the senses. We apologize for any confusion or inconvenience this may cause, and hope you find the update useful!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![Compare and contrast on [Flickr]. Happy Birthday Blog!](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4019/4539503542_1e41294e95.jpg)