Everybody's doing it: rolling their own searches. Rollyo lets you create and share domain-specific searches. In the space of a few minutes, you can register, select a bunch of websites to limit a search to, and then link to the resulting "personal search engine."

For instance, if you wanted cut through a lot of the noise which normally turns up in a search for our hero, you can type in a few keywords in the search box for "Henry Reed."

Rollyo is running a plain, vanilla Yahoo! Search in the background, which makes it slightly less accurate than using, say, a9.com, which runs on Google. Because the search pages are user-created, however, most of the gruntwork and vetting is already done. Human-editing is what made Yahoo! such a great tool to begin with.

And, for the benefit of gawking and abuse, there's a "My Rollyo" feature which allows you to save your favorite searchrolls, and propel the elite to "High roller" status.

|

Roll Your Own Search

The Sensual Book SaleI was surprised to find today, at "The Friends of the Library" used book sale, a striking number of sex books. Marital Aid-this, and Human-Sexuality-that. Titles that made me smile, then blush. The Pictoral Book of Sex. Sexercises. I'm the type who flips cautiously through coffeetable art books, lest the pages fall open at a particularly baudy nude by Titian or Botticelli.

When I first walked in, it was obvious the sale was a sort of barely-restrained chaos: a great square of tables, with people circling in both directions. As it was already an hour after opening, I circled left. Logic dictated that most of the herd would automatically turn right, and the less-picked over titles would be in the opposite direction. There was no attempt at any sort of organization. Books were just randomly laid on the tables in three rows, spines up, with little piled ziggurats bookending the loose ends. At one point, a guy next to me asked if I knew how the books were organized. Alphabetically? By subject? I told him, "The books are arranged... horizontally." As empty spaces appeared in the rows, volunteers would heap more books into the holes like cordwood, from boxes under the tables. The library's "Friends" get early admittance to these sorts of sales and as a result, by the time I arrived, there were great levees of books stacked against the walls, with slips of paper on top that read, "SOLD." Hoarders and bookdealers were breaking these piles down into boxes to be carted off to compulsive collections, storefronts, and eBay. The books were a curious amalgam of donations which could not be reckoned within the scope of the library's collection, withdrawn titles, and great masses of texts which must of come directly out of some retiring professor's office. Whole tables of books on the ethics of euthanasia, machine learning, Jewish history, and plays and pulp novels in French. There also smelled to be a higher-than-average number of Patchouli wearers present at the sale. Why do otherwise-attractive people insist on cloaking themselves in what amounts to the olfactory version of blasting their car stereo? Why are so many of them attracted by the lure of cheap books? I spent a glorious, contented, three hours at the sale, making two complete passes over the tables, but didn't come away with any treasures. I found a copy of Perrine's Sound and Sense (which I probably already own a copy of). A theatre book of the script for Breaking the Code, by Hugh Whitemore, based on Hodges' book Alan Turning: The Enigma. A paperback on Australian literature, with a chapter on the Ern Malley poems. My prize was a 1958 Grove Press edition of Three Plays by Ugo Betti, translated by Henry Reed. My heart leapt when I saw Reed's name in bold, white letters on the spine, hiding amidst an ancient pile of German literature in hardcover.

Indexing the IndexesOr, if you're a stickler, Indices.

When I first got hooked on Henry Reed, I didn't really know how to go about tracking down sources. There was Granger's Index, sure; and the fledgling Internet helped a little (although, a lot of stuff was still being released on CD-Rom, at that time. Ah! The 'Nineties.). Mostly, I was following breadcrumbs: the footnotes in one article would lead me to two others, which led me to three others, et cetera, et cetera, ad infinitum. I'm proud that I did it that way. It was hard work. Detective work. But recently, I discovered a lot of time and effort could have been saved had I just spent a couple of afternoons and evenings going shelf by shelf, title to title, in the Reference section of the university library. Reed is hardly obscure. The Lessons of the War and "Chard Whitlow" are widely anthologized. His radio work for the BBC placed him in another milieu entirely, an extensive range. I'm convinced that you cannot swing a cat, living or dead, in any library with the Library of Congress call number "P," without hitting a book that mentions Reed. So, taking Vizzini's advice, I go back to the beginning. To see if there was anything I missed. I've spent the last few evenings after work prowling indexes for never-before seen citations: anthologies, biography, explication, and just plain passing mention. I'm literally tanned from standing over an open photocopier, repeatedly turning heavy volumes on the glass like steaks on a barbeque. The latest Granger's Index to Poetry was the largest boon, naming at least a dozen anthologies to track down and look up. The library has a 2002, 12th edition, whereas at home I'm stuck with an 8th that I plucked from the donation box of the first public library I worked for (I miss getting first paws on the duplicates donated to the Public Library System. Sigh). The 12th actually has an entry for Reed's "Dull Sonnet," which is obscure enough that even I had to go look it up. But I also turned up the index to a set called Modern British Literature, compiled and edited by Ruth Z. Temple, et al. Alas, the university only owns the American half of the series. I see a field trip in my future.

I Also Like to Pick Up TeethWhen I'm not being crazy-obsessive about a certain lesser-known English poet, I like to unwind on a nice, pebbly beach, with my feet in the river and the sand squishing up between my toes, and pick up fossil shark teeth.

ErrataOne thing which irks me to no end is a sort of misinformed deja vu I experience when I find myself staring at a page I must have looked at months or years before, and realize I had discovered ages ago that it was a dead end or misquote or incorrect citation. I probably tore up my colored index card in disgust, only to be tricked again at a later date. So rather than dedicating another drawer of the card catalog solely to "Erratum," I thought I would edit this space each time I find someone mistaken or something misleading.

Alexander, Harriet S., comp. American and British Poetry: A Guide to the Criticism. Athens, Ohio : Swallow Press, 1984. 320. Mistakenly places "Naming of Parts" under the entry for Herbert Read. Beggs, James S. The Poetic Character of Henry Reed. Hull, England: University of Hull Press, 1999. 144. "Privately, Thomas had chastised Henry Treece's 'ridiculous overpraise of Reed' and labelled most of Reed's poetry 'dull' (Letters 223)." Dylan Thomas (and Henry Treece) is actually referring to Herbert Read. Cleverdon, Douglas. Obituary for Henry Reed. Independent (London). December 11, 1986. "'Vincenzo', in 1950, presented the life Vincenzo Gonzaga in a dramatised form...." Reed's radio play, Vincenzo, was first broadcast in 1955. Gunter, Liz and Jim Linebarger. "Tone and Voice in Henry Reed's 'Judging Distance'." Notes on Contemporary Literature 8, no. 2 (March 1988): 9. An unfortunate typographic error leaves the "s" off the end of "Judging Distances." Hamilton, Ian. "Henry Reed." In Against Oblivion: Some Lives of the Twentieth-Century Poets. London: Viking, 2002. 216. Hamilton, of all people, refers to the "Lessons of the War" sequence as "Lessons of War." Kermode, Frank. "Part and Pasture." London Review of Books, 5 December 1991, 17. "[T]he epigraph to 'Lessons of the War' — vixi puellis nuper idoneus/et militavi non sine gloria — substitutes puellis, 'girls', for Horace's duellis, 'wars'." Horace spoke of 'puellis' (girls), and Reed substituted 'duellis' (battles), not the other way around. Here's Ode III:26 in English, and Latin. "Catherine Carver, who sorted out the heaps of drafts, clippings and corrections left by the poet...." Correct spelling is "Catharine" Carver. Marcus, Laura, and Peter Nicholls, eds. The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century English Literature. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2005. 479. "For those who tuned in, radio now disseminated avant-gardism much more widely than fringe theatres, premiering Henry Reed's influential translations of Brecht." Either the editors meant Betti instead of Brecht, or they have the wrong translator. O'Toole, Michael. "Henry Reed and What Follows the 'Naming of Parts'." In Functions of Style, edited by Davis Birch and Michael O'Toole. London: Pinter Publishers, 1988. 13. The entirety of "Naming of Parts" is presented in this chapter, but the author leaves out the all-important "the" from "Lessons of the War." Patey, Douglas Lane. The Life of Evelyn Waugh: A Critical Biography. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998. 290, 399n. Patey quotes Reed's 1950 review of Waugh's Helena, but incorrectly cites the article as "30 Sept. 1950, 515." The review was actually published November 9th. Peacock, Scot, ed. "Henry Reed 1914-1986." In vol. 78, Contemporary Authors. New Revision Series. Detroit: Gale Group, 1999. 410. "Reed began writing while a student at Birmingham University, where his circle of friends included writers W. H. Auden, Walter Allen, and Louis MacNeice." Auden was seven years Reed's senior, and went to Christ Church, Oxford, not the University of Birmingham. Auden's father was Professor of Public Health at the the University, and it's entirely possible that Reed may have met Auden when he visited. But to call them 'friends' is probably an exaggeration. Tolley, A.T. The Poetry of the Forties. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1985. 48, 209. Tolley refers to "Lessons of the War" as "Lessons of War," no less than twice. Wakeman, John, ed. "Reed, Henry." In World Authors, 1950-1970. New York: H.W. Wilson, 1975. 1199. "[Reed] has published a number of prose translations, notably of Flaubert." It's likely the author of this article is confusing Reed's translations of Balzac's novels, as I can find no evidence he ever published any translations of Flaubert. Wolosky, Shira. The Art of Poetry: How to Read a Poem. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. 8-10, 18-19, 172.. Repeatedly refers to "Naming of Parts" as "Today We Have Naming of Parts."

Girls on CoversI had opportunity today to drop into Mermaid Books, a little, hole-in-the-wall used bookstore in town. I would recommend dropping in if you are at all able. Not only do they receive a good portion of the obscure and well-read books from town, but any bookshop which advertises "Ephemera" as a category has got to be worth a poke-around.

Today I happened upon a copy of Richard Brautigan's collection The Pill versus the Springhill Mining Disaster. Brautigan has been one of my favorite poets ever since I came across his poem, "Discovery," in a collection of San Francisco poets. The petals of the vagina unfoldI believe I was drinking a Mr. Pibb in the Food Court at the mall, at the time. You may know Brautigan for being the progenitor of the phrase "machines of loving grace." Brautigan's poems aren't poems at all; they're more like prayers, or black and white photographs. Small pieces of time frozen long enough to get a good look at. The Pill is dedicated to "Miss Marcia Pacaud of Montreal, Canada," who is pictured, barefoot on a pile of rubble, on the cover. No title, no author. No text whatsoever. This striking image happily led me to the Brautigan "Girls on Covers" webpage.

Easing the SpringWhen I started the "Reeding Lessons" weblog, one of the things I thought it would allow me to do was extoll and expound on Reed's poems myself, something which I have been hesitant to do on the main site (with one notable exception).

Having seen several folks searching for the phrase "easing the spring" this week, it seems a logical place to begin. In Reed's poem, "Naming of Parts," the play on the phrase "Easing the Spring" appears three times: twice in the fourth stanza, and once in the fifth and final stanza. In the fourth stanza, the word "spring" is printed both in lowercase and capitalized. The first reference to "spring" is mechanical and literal: this is the metal spring in the rifle's magazine which forces the cartridges up into the breech to be fired. The second and third appearances of the word are in uppercase, "Spring," referring to the season. The stanzas of the poem are divided into two parts: the first three lines of each are of the recruit listening to the lesson on the parts of his rifle; the fourth line is a blending of the actual lesson and the recruit's interpretation; and the fifth and sixth lines complete the inner monologue of the recruit trying to make sense of what he is being taught. Thus, in stanza four: The contrast between the mechanized, military spring and natural, bee-filled Spring is obvious. No matter how hard the young soldier concentrates on his arms lesson, his thoughts always revert to Spring, love, and the mechanics of sex. Reed lifted the phrase "Easing the spring" directly from his basic training. Chapter IV, Section 52 of the Manual of Elementary Drill (All Arms), 1935, contains instructions for the inspection of arms. Part of this procedure is the order "Ease—Springs." The object of a soldier easing the spring is to remove all tension from the mechanical parts of the rifle. Literally, the easing of the rifle's spring requires ejecting any and all cartridges from the magazine, thus rendering it safe for inspection by an officer. 4. To ease springs, or charge magazines and come to the order.I find it particularly interesting that the word "easing," because of the line breaks, is capitalized in line four, and in lowercase at the close of the stanza. Note also the phrase 'rapidly backwards and forwards,' which Reed also utilizes in "Naming of Parts." The British Lee-Enfield rifle Henry Reed would have been trained on held two clips of five cartridges apiece. The "cut-off" mentioned in the drill instruction was a plate which could be slid into place to cut the magazine off from the breech, allowing the rifle to be fired as a single-loader, with the contents of the magazine held in reserve for heavy combat, thus saving ammunition. However, the inclusion of a magazine cut-off was retired after World War I, the tactics of warfare having shifted in favor of expending more ammunition against an enemy or target. Reed may have a made a conscious choice to exclude the cut-off from his lesson on naming of parts, or possibly the cut-off was just another something which he "had not got."

The Kindness of StrangersThe pictures page is sporting two new images, both of which were generously provided by people whom I've never met. I am constantly, continuously amazed by the help I receive in my research endeavors. Librarians, clerks, and docents reply to my querulous emails, answering my ridiculously unimportant questions, often taking the time to send photocopies, pamphlets, and lengthy letters through the mail.

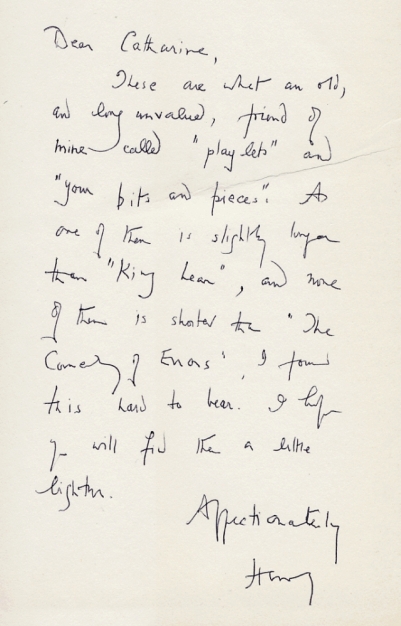

After I posted here about Weldon Kees' affection for Reed's poetry, I received an email from the poet and Kees biographer, James Reidel, who was kind enough to provide me with a digital copy of the image I had posted, from his personal collection. Mr. Reidel also alerted me to the imminent publication of the next issue of The Ephemera, which contains his latest effort on Kees: "A Portfolio of Photographs: By Him, Attributed, Performed, Collected." I also re-connected with Chris, my British counterpart at Webrarian.co.uk, who collects all things related to Reed's radio plays (which my site painfully neglects); in particular, the Hilda Tablet series. Chris recently discovered a copy of The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio which contained a dedication in Reed's handwriting: The inscription reads: Dear Catharine,The most likely recipient of this copy of The Streets of Pompeii would have been Catharine Carver, who is credited by Jon Stallworthy with sorting through Reed's notebooks and personal papers for the publication of the Collected Poems. Carver was a well-respected editor for several publishing houses, including Chatto and Windus, Harcourt Brace, Viking, and Oxford University Press. At some point, she worked for Victor Gollancz, possibly at the time they published Reed's translation of Three Plays by Ugo Betti (London: 1956). Carver also assisted the biographer Michael Millgate with his collections Thomas Hardy's Public Voice, and Letters of Emma and Florence Hardy, and Millgate had previously acknowledged Reed for some assistance in Thomas Hardy: A Biography. Perhaps Carver had some Hardy dealings with Reed? In his Preface for The Complete Poems of Keith Douglas, Desmond Graham mentions that Carver died in 1991 (p. xii).

Kleinian ConnectionI've been absent awhile. Not without leave, necessarily. Today was my twenty-first straight day at work. Classes have begun, and I had a brace of new students to train. Their training now complete, I have tomorrow and the Labor Day holiday off. A two-day pass.

I did happen upon this page, a critique of "Naming of Parts" with a Freudian bent. I wonder what Henry would make of it? I don't imagine Reed was the sort of Professor to wield a deadly red pen. I can see him making small revisions of text with a fountain pen, cross-outs and underlining, notes in the margins, but I think he would reserve the bulk of his criticism for the space at the end of an essay, where he could spread out and write in full-length sentences. He most certainly would have disagreed with the conclusions of this particular essay, but he did subscribe to Freudian theory, inasmuch as developed by the Austrian psychoanalyst Melanie Klein. Reed claimed to keep Klein's book, Narrative of a Child Analysis, 'on the same shelf as Finnegans Wake and War and Peace.' (Listener 65, no. 1667 [9 March 1961]: 445-6.) Reed is even mentioned in this interview with Betty Joseph, possibly a friend from the University of Birmingham.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||