|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Betti"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

An obituary for Henry Reed appears in most surprising place: the classic New York/Hollywood entertainment rag, Variety. How does an arguably obscure British poet rate such an honor, might you ask? Because of Reed's surge of translations of Italian plays for the stage in London during the mid-1950s, which culminated in a New York production of Ugo Betti's Island of Goats at Broadway's Fulton Theatre in October, 1955. The play was a box office disaster and closed after only four days, resulting in the trademark varietyese™ headline:

Anyway, Foreign Crix Liked Flopperoo 'Goats'

Anyway, Foreign Crix Liked Flopperoo 'Goats''Island of Goats,' a recent flop on Broadway, had foreign appeal on both sides of the Atlantic. Having previously clicked in Paris, the show repeated with the foreign press reviewers in N. Y. It drew unanimous pans from the first-string Broadway critics.

The Ugo Betti drama, adapted by British playwright Henry Reed, folded Oct. 8 at the Fulton Theatre, N. Y., after seven performances. Following the windup performance, Saul Colin, a member of the Stage & Screen Foreign Press Club, took over the stage to praise the play, noting that 80% of the foreign publication aisle-sitters had turned in favorable notices.

Colin also shook hands with the entire cast, who had been standing on one foot and then the other.

[October 19, 1955, p. 71]

And here's Reed's aforementioned Variety obit, from the New York edition, January 7, 1987, p. 151:

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

Really excellent finds this week. The first was only a short quote by Elizabeth Bowen, which mentions Reed. Sorting out the context for that will require a little more time to nail down all the corners.

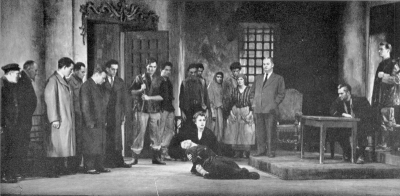

But the other was in volume 7 of Theatre World Annual (London), which covers June 1st, 1955 to the 31st of May, 1956. It includes reviews and pictorials for two of Henry Reed's adaptations of Ugo Betti's plays, which were performed in London in the fall of 1955. The first of these was The Queen and the Rebels, which opened at the Haymarket Theatre on October 26th. Theatre World editor, Frances Stephens, called Reed's translation "taut and effective." Pictures by Angus McBean (apologies for my poor scans):

A moment from the opening scene of the play, which takes place in a large hall in the main public building in a hillside village near the frontier. Raim (Duncan Lamont) is interrogating a number of travellers, who have been forcibly held up at this remote spot by the revolutionary forces; among them Argia (Irene Worth, center. Later, left alone, Argia, a prostitute from the neighboring town, reveals that she had made the journey specially to find Raim. [Page 73.]

Raim indulges in some indiscreet talk with one of the travellers, only to discover later that he is Commissar Amos of the Revolutionary Party (Leo McKern, right)

The Queen, whose only desire is to get away, believes pathetically that Argia will help her. At the last moment Argia relents and helps her to escape the trap laid by Raim. The soldiers wrongly think that it was Argia who was trying to escape and report to Amos, who already has his suspicion about this unknown woman. He begins to question her. [Page 74.]

It is now obvious that the revolutionaries are convinced that Argia is the Queen and for the moment she revels in deceiving Biante, the General of the revolutionary forces, who has come back severely wounded from the fighting in the hills (Alan Tilvern).

The Queen has already been captured and having, through Argia's influence, gained a little courage, she is at last brave enough to take her own life. But Argia has now lost the one witness who might have saved her. She is sentenced to death, and later refuses to sign a trumped-up confession. [Page 75.]

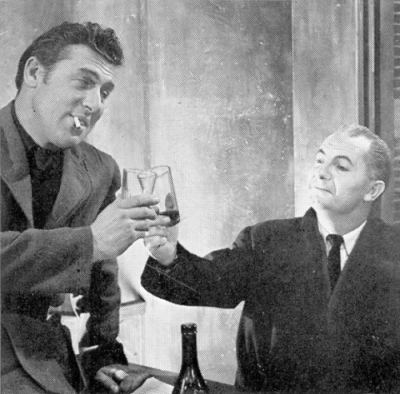

In contrast to the intensity of Betti's Queen is Reed's "charming" translation of Summertime, which premiered at the Apollo Theatre, London, on November 9th, 1955. Pictures by Armstrong Jones:

Francesca (Geraldine McEwan, left) is determined to marry Alberto (Dirk Bogarde, right). She entices him, reluctantly, to a picnic in the mountains, where he confesses he has already innocently compromised himself with a girl in the city. (Centre: Michael Gwynn as the Doctor.) [Page 79.]

Aunt Ofelia (Esma Cannon), who is Alberto's aunt, and Aunt Cleofe (Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies) aunt to Francesca. These two have been watching the proceedings from a distance. Aunt Cleofe is anxious for Francesca to marry the young doctor, but in the end—as one might have expected—the girl forgives Alberto and the unfortunate young medico is sent packing.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

In the year 1737, upon receiving word of the impending production of a particularly unfavorably satire of the rule of King George II, British Parliament passed the Theatrical Licensing Act, requiring that no person shall for hire, gain or reward, act perform, represent, or cause to be acted, performed or represented any new interlude, tragedy, comedy, opera, play, farce, or other entertainment of the stage, or any part of parts therein; or any new act, scene or other part added to any old interlude, tragedy, comedy, opera, play, farce or other entertainment of the stage, or any new prologue or epilogue, unless a true copy thereof be sent to the Lord Chamberlain of the King's household for the time being, fourteen days at least before the acting.... The Act ( full-text) called for the Lord Chamberlain and his Examiners of Plays to review and, where necessary, censor potential scripts before they reached the stage, with the intent of protecting the corruptible public. At the time, plays were already restricted to performances in theatres which had been granted royal patents. The Patent Act was repealed in 1843, but the Licensing Act remained intact until 1968.

Reed had adapted Ugo Betti's play, Crime on Goat Island, for the BBC's Third Programme in 1956. His translation had already appeared on the stage in 1955, at New York's Fulton Theatre. In 1957, however, a production was planned for the Oxford Playhouse, which ran into a "spot of bother" with the Lord Chamberlain's Office.

A very helpful gentleman at the British Library, Arnold Hunt, emailed me that the Manuscript Collections contain the original typescript submitted for examination (with the famous blue pencil marks of the censors), as well as additional correspondence detailing the debate over Reed's version of Betti's play. Mr. Hunt writes: “On 3 November 1957, the Assistant Examiner, St. Vincent Troubridge [a descendant of Lord Nelson], reported that he was not prepared to recommend the play for licence. 'The story of this play, condensed into a couple of sentences, is that to the widow of a Professor living on a remote goat-farm with her daughter and sister-in-law, there appears an attractive young man, claiming to have been friendly with the Professor in a war-time captivity. He proceeds to have sexual intercourse with all these three closely related women in turn, the widow on the first night of his arrival. A few weeks later they murder him down a well. This to my mind is a great deal too farmyard to be permissible in common decency on the public stage.'” The examiner's synopsis is fair, even if he was taking his responsibilities a bit too seriously (read more about how censorship shaped modern British theatre). The script was eventually deemed "'sordid and revolting,' but not injurious to morals," and the play was granted a license to be performed, hinging on the removal of one passage, which Troubridge described as 'sodomy in reverse, about goats trying to make physical love to their goatherds.' Angelo, the scroundrel of the play, tells a story of how goats in his country sometimes fall in love with their goatherds: And eventually the shepherd begins to understand, and after a little while they... make love, there in the meadows, pressing close together, closer than a man and woman even. (Act I, scene iv.) To the credit of his station, the Lord Chamberlain himself, the Right Honourable Lawrence Roger Lumley, 11th Earl of Scarborough, commented "I don't feel very strongly about the ordinary sex part, but I do draw the line at the goats."

(Coincidentally, the composer Donald Swann, who wrote the music for Reed's Hilda Tablet plays, mentions his regret at never having anything of his banned by Lord Scarborough, whom he called a "charming chap.")

Crime on Goat Island opened in Oxford on December 2nd, 1957. The following day, the Times' special correspondent reported weakness in Betti's plot and doubt in Reed's script: "The jealousy between the three women, the division in the household: these are real enough. But as Betti and his translator Mr. Henry Reed handle them they subtract from the interest of the characters instead of adding to it." No mention is made, however, of lovesick goats (The Arts, 3 December 1957, 3).

A history of censorship and its effects on British theatre was published last year: The Lord Chamberlain Regrets: British Stage Censorship and Readers' Reports from 1824 to 1968 ( Amazon.com US).

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

I was surprised to find today, at "The Friends of the Library" used book sale, a striking number of sex books. Marital Aid-this, and Human-Sexuality-that. Titles that made me smile, then blush. The Pictoral Book of Sex. Sexercises. I'm the type who flips cautiously through coffeetable art books, lest the pages fall open at a particularly baudy nude by Titian or Botticelli.

When I first walked in, it was obvious the sale was a sort of barely-restrained chaos: a great square of tables, with people circling in both directions. As it was already an hour after opening, I circled left. Logic dictated that most of the herd would automatically turn right, and the less-picked over titles would be in the opposite direction.

There was no attempt at any sort of organization. Books were just randomly laid on the tables in three rows, spines up, with little piled ziggurats bookending the loose ends. At one point, a guy next to me asked if I knew how the books were organized. Alphabetically? By subject? I told him, "The books are arranged... horizontally." As empty spaces appeared in the rows, volunteers would heap more books into the holes like cordwood, from boxes under the tables.

The library's "Friends" get early admittance to these sorts of sales and as a result, by the time I arrived, there were great levees of books stacked against the walls, with slips of paper on top that read, "SOLD." Hoarders and bookdealers were breaking these piles down into boxes to be carted off to compulsive collections, storefronts, and eBay.

The books were a curious amalgam of donations which could not be reckoned within the scope of the library's collection, withdrawn titles, and great masses of texts which must of come directly out of some retiring professor's office. Whole tables of books on the ethics of euthanasia, machine learning, Jewish history, and plays and pulp novels in French.

There also smelled to be a higher-than-average number of Patchouli wearers present at the sale. Why do otherwise-attractive people insist on cloaking themselves in what amounts to the olfactory version of blasting their car stereo? Why are so many of them attracted by the lure of cheap books?

I spent a glorious, contented, three hours at the sale, making two complete passes over the tables, but didn't come away with any treasures. I found a copy of Perrine's Sound and Sense (which I probably already own a copy of). A theatre book of the script for Breaking the Code, by Hugh Whitemore, based on Hodges' book Alan Turning: The Enigma. A paperback on Australian literature, with a chapter on the Ern Malley poems.

My prize was a 1958 Grove Press edition of Three Plays by Ugo Betti, translated by Henry Reed. My heart leapt when I saw Reed's name in bold, white letters on the spine, hiding amidst an ancient pile of German literature in hardcover.

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|