|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Translations"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

The PN Review has revamped their website in the last year, adding a searchable index and full content for subscribers. Non-subscribers can still access the first few paragraphs of articles, as a preview.

Back in 2008, the PN Review featured Henry Reed's (until then) unpublished translations of Nobel Prize-winning Eugenio Montale's mottetti, edited by Marco Sonzogni, who provided a fascinating afterword describing Reed's manuscripts at the University of Birmingham.

On the PN review you can see a preview of Reed's translation of the first of Montale's motets:

The Pledge [Motet I] Lo sai: debbo riperderti e non posso.

Come un tiro aggiustato mi sommuove

ogni opera, ogni grido e anche lo spiro

salino che straripa

dai moli e fa l'oscura primavera

di Sottoripa.

Paese di ferrame e alberature

a selva nella polvere del vespro.

Un ronzío lungo viene dall'aperto,

strazia com'unghia ai vetri. Cerco il segno

smarrito, il pegno solo ch'ebbi in grazia

da te.

E l'inferno è certo. Several folks wrote letters to the Review following the publication of the Mottetti, to argue some of the finer points of Reed's translations. This issue and others are available for purchase from the Carcanet website.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

Here's a excerpt from an article on Honoré de Balzac, in the Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, v.1, edited by Olive Classe (London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2000). Written by Michael Tilby, the article contains this bit of a love note to Reed's translation of Balzac's Eugénie Grandet (New York: New American Library, 1964). Tilby calls Reed's adaptation "inherently Balzacian," "outstanding," and to be "preferred to its rivals."

The 1964 translation by the poet and radio dramatist, Henry Reed takes the text of the last version to be revised by the author (the so-called 'Furne corrigé') but follows the Garnier edition of 1961 in restoring 'Balzac's shapely design of the edition of 1834'. It also includes the opening and closing paragraphs, to which only readers of the anonymous 1859 translation had previously had access in English. Further emendations are discussed by Reed in a lengthy translator's note. They include, controversially, the correction of what the translator identifies as the printer's wrongly positioned insertions of Balzac's marginalia (though without apparently checking his intuitions against the manuscript or that portion of the corrected proof that survives). Reed also tidies up, as far as possible, Balzac's own, incomplete, alterations of dates and the ages of certain of his characters. 'Grandet no longer puts on a couple of decades in the space of 12 to 14 years and ... Madame Grandet does not die both in 1820 and 1822'. A similar attempt is made to substitute 'a more logical time-scheme' for Balzac's 'grotesque miscalculations connected with the central action'.

Reed's actual translation is outstanding and is to be preferred to its rivals. It modernized the original in precisely the way Milton Crane claimed for Bair's version and avoids the errors and distortions that disqualify Crawford's. Consistently resourceful, it is inherently Balzacian through the translator's own relish for words. Alone of all the published English translations, it brings the characters alive through their speech, as in this case of an outburst by the Grandet's servant, offered a small glass of cassis from the bottle she was carrying when she tripped on a rickety stair: 'In my place, there's plenty what would have broken the bottle. I held it up in the air and nearly broke my elbow instead'. [p. 103]

I'm ashamed to admit, while I've read Reed's translation of Père Goriot, I haven't actually read his Eugénie Grandet, because my used bookstore copy is in such good condition, I don't want to ruin it!

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

What else should I call the tale of how Henry Reed almost became a scriptwriter for a 1970s biopic on King Abdul Aziz Al Saud? It's a strange story of anonymous sheikhs, the clash of egos in the film industry, disappearing money, and mistaken identity.

In 1975, the director Joseph Losey was approached with an offer to make a feature film about the life of Ibn Sa'ud, the first ruler of Saudi Arabia. Funding for the project was to come from an anonymous source, negotiating through a firm of London solicitors.

Losey hired Barbara Bray to perform research, and to translate. The Algerian writer, Kateb Yacine, provided a script in French, but his efforts proved disappointing. Negotiations were made with writers Ring Lardner, Jr., and Robert Bolt, but Lardner wanted too much money, and Bolt was "too indoctrinated with Lawrence." Finally, a script was ordered from Franco Solinas, who had previously worked on Losey's Mr. Klein. By now, several years have transpired, and it is at this point in the story that Reed makes his appearance. From David Caute's 1994 biography, Joseph Losey: A Revenge on Life (p. 455):

Now a fatal row blew up. Patricia Losey had been translating Solinas's pages from the Italian as they arrived. Barbara Bray, who didn't appreciate Losey's habit of 'smuggling' his wife in to the work she herself was engaged on, suggested that the script should be translated into English by the poet and radio playwright (Prix Italia, 1951) Henry Reed, who was also the translator of Leopardi and Ugo Betti. The solicitor Peter Stone duly informed Losey that his clients wished to engage 'a first-class literary translator...' Losey was furious: 'I was amazed and appalled at the brutality of your libel by implication of Patricia's work...' To make matters worse Losey persistently referred to Henry Reed as 'Herbert Reed', i.e. the art critic, Sir Herbert Read. Having read 'Herbert Reed's' translation, he declared it inferior to Patricia's: 'I cannot begin to describe to you my rage and perplexity... [your] insensitivity and discourtesy... after Don Giovanni I am quite sure that Patricia's name will be far more known to the mass audiences that Herbert Reed's [ sic].' Worse was to come: the principals put the entire project, plus finance, in the hands of London-based Palestinian entrepreneur Naim Atallah, who promptly dropped Losey.

I was unsure how Barbara Bray might have known Reed, apart from his translations. Then I came across this Wikipedia stub. Bray had been a script editor at the BBC in the 1950s, until she became involved with the playwright Samuel Beckett and moved to Paris in 1961, where she became a well-respected translator, herself.

Ibn Saud was never made, and Solinas's script remained unpublished until after his death in 1982.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

Here's a great resource which has been making the rounds in various blogs this last week: Stanford University Libraries' Copyright Renewal Database. Here's why it's important:

The period from 1923-1963 is of special interest for US copyrights, as works published after January 1, 1964 had their copyrights automatically renewed by the 1976 Copyright Act, and works published before 1923 have generally fallen into the public domain. Between those dates, a renewal registration was required to prevent the expiration of copyright, however determining whether a work's registration has been renewed is a challenge. Renewals received by the Copyright Office after 1977 are searchable in an online database, but renewals received between 1950 and 1977 were announced and distributed only in a semi-annual print publication. The Copyright Office does not have a machine-searchable source for this renewal information, and the only public access is through the card catalog in their DC offices.

The database only contains U.S. Class A (book) copyright renewals.

Henry Reed appears three times in Stanford's catalog, for the American editions of some of his translations: Perdu, by Paride Rombi; Père Goriot, by Honoré de Balzac; and Three Plays, by Ugo Betti (copyright renewed by Reed himself, in 1984!).

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

So, I had my credit card info stolen this week. That was fun. You should have heard the conversation I had with customer service when I called to cancel the card: Amazon.com? No, that charge is legitimate. Barnes & Noble? Yeah, that was me, too. Abebooks.com? Okay, if it was for books, then it was probably me. A new card should come this week.

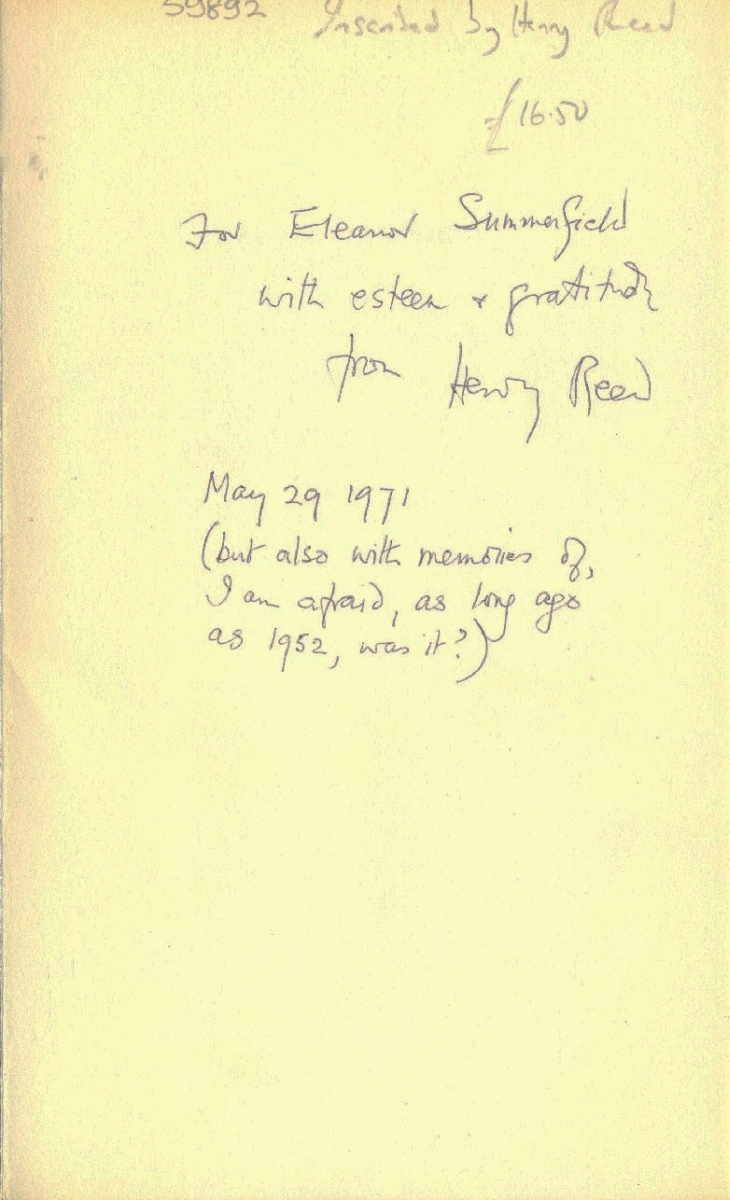

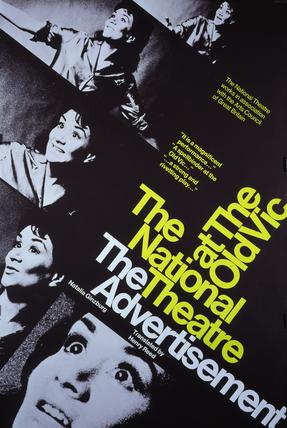

This month's extravagence was a signed copy of Natalia Ginzburg's The Advertisement ( L'Inserzione), published in 1969 by Faber and Faber, and translated from the original Italian by our very own Henry Reed. I don't usually bother with first editions or signed copies, but I felt like I deserved a treat.

Now, I must admit, I have only a passing interest in Reed's translations. What I'm really after is completeness, an inclusive collection. Even the items I'm least interested in may turn out to contain an overlooked fact or hidden clue to some larger mystery, rounding out Reed's bio-bibliography (biblio-biography?). This edition of Ginzburg's play, for instance, has a brief "Translator's Note" written by Reed, the details of the first stage performances in London, and a jacket blurb from a Daily Telegraph review: 'From the moment this very interesting play takes shape, it is clear that a tour de force is necessary from the actress playing Teresa; and Joan Plowright rises to the challenge quite superbly.'

And then there is the inscription to my newly-acquired copy:

For Eleanor Summerfield

with esteem + gratitude

from Henry Reed

May 29 1971

(but also with memories of,

I am afraid, as long ago

as 1952, was it?) Ms. Summerfield (BBC obituary), I was delighted to discover, was an accomplished actress, with a litany of film (Internet Movie Database) and radio (BBC Programme Catalogue) credits to her name. She was married to the actor Leonard Sachs for 40 years (though she could claim Sir Richard Burton among the paramours of her youth.) I imagine Reed was introduced to Summerfield while he was writing for the Third Programme. How they became reacquainted in 1971, I have no idea. At the BBC, again?

To see more on this book and and others by Reed, take a peek at my bookshelf on LibraryThing.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

Really excellent finds this week. The first was only a short quote by Elizabeth Bowen, which mentions Reed. Sorting out the context for that will require a little more time to nail down all the corners.

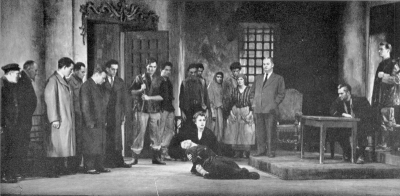

But the other was in volume 7 of Theatre World Annual (London), which covers June 1st, 1955 to the 31st of May, 1956. It includes reviews and pictorials for two of Henry Reed's adaptations of Ugo Betti's plays, which were performed in London in the fall of 1955. The first of these was The Queen and the Rebels, which opened at the Haymarket Theatre on October 26th. Theatre World editor, Frances Stephens, called Reed's translation "taut and effective." Pictures by Angus McBean (apologies for my poor scans):

A moment from the opening scene of the play, which takes place in a large hall in the main public building in a hillside village near the frontier. Raim (Duncan Lamont) is interrogating a number of travellers, who have been forcibly held up at this remote spot by the revolutionary forces; among them Argia (Irene Worth, center. Later, left alone, Argia, a prostitute from the neighboring town, reveals that she had made the journey specially to find Raim. [Page 73.]

Raim indulges in some indiscreet talk with one of the travellers, only to discover later that he is Commissar Amos of the Revolutionary Party (Leo McKern, right)

The Queen, whose only desire is to get away, believes pathetically that Argia will help her. At the last moment Argia relents and helps her to escape the trap laid by Raim. The soldiers wrongly think that it was Argia who was trying to escape and report to Amos, who already has his suspicion about this unknown woman. He begins to question her. [Page 74.]

It is now obvious that the revolutionaries are convinced that Argia is the Queen and for the moment she revels in deceiving Biante, the General of the revolutionary forces, who has come back severely wounded from the fighting in the hills (Alan Tilvern).

The Queen has already been captured and having, through Argia's influence, gained a little courage, she is at last brave enough to take her own life. But Argia has now lost the one witness who might have saved her. She is sentenced to death, and later refuses to sign a trumped-up confession. [Page 75.]

In contrast to the intensity of Betti's Queen is Reed's "charming" translation of Summertime, which premiered at the Apollo Theatre, London, on November 9th, 1955. Pictures by Armstrong Jones:

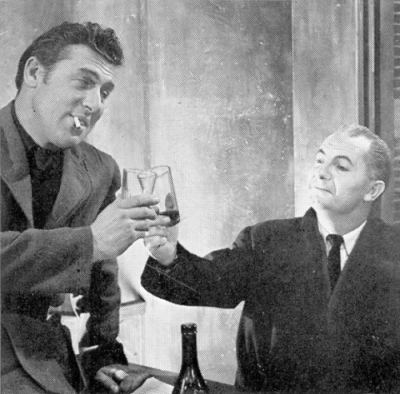

Francesca (Geraldine McEwan, left) is determined to marry Alberto (Dirk Bogarde, right). She entices him, reluctantly, to a picnic in the mountains, where he confesses he has already innocently compromised himself with a girl in the city. (Centre: Michael Gwynn as the Doctor.) [Page 79.]

Aunt Ofelia (Esma Cannon), who is Alberto's aunt, and Aunt Cleofe (Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies) aunt to Francesca. These two have been watching the proceedings from a distance. Aunt Cleofe is anxious for Francesca to marry the young doctor, but in the end—as one might have expected—the girl forgives Alberto and the unfortunate young medico is sent packing.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

Several books mention Reed's translations of Ugo Betti dramas as being produced for the London stage in 1955. Stallworthy, for instance, says in the Dictionary of National Biography: "Several of his translations found their way into the theatre, and in the autumn of 1955 there were London premières of no fewer than three." Quite an accomplishment. Reed adapted quite a few of Betti's plays for radio, however. So many in fact, that I am frequently confused as to the order they were produced.

Betti's play La Regina e gli Insorti was written in 1949. Commissioned by the BBC's Third Programme, Reed translated and adapted the play for radio, and The Queen and the Rebels was broadcast on October 17, 1954. The radio versions of all three plays were produced by Donald MacWhinnie.

Next came Betti's L'Ainola Bruciata, written 1951-52. Translated as The Burnt Flower-Bed, the play was broadcast on the Third Programme on January 3, 1955.

The third play, Summertime, began as Il Paese delle Vacanze (1937). It was broadcast as Holiday Land on the Third Programme on June 6, 1955.

The Burnt Flower-Bed was premièred live at the Arts Theatre, London, on September 9 of that year.

Subsequently, The Queen and the Rebels opened at the Haymarket Theatre, London, on October 26.

Finally, a version of Holiday Land was revised as Summertime, opening at the Apollo Theatre, London, on November 9, 1955.

Oddly enough, Reed's autobiographical entry for Who's Who mentions the publication of these translations as Three Plays (1956), but neglects any of the London stage productions. It does, however, make note of Betti's Crime on Goat Island being 'staged NY 1960', but the only notable production of Goats in New York (starring Laurence Harvey, Uta Hagen, and Ruth Ford) was also in 1955, not 1960.

And as a footnote, Reed's biographical entries in Contemporary Authors and Contemporary Poets both list a play titled Summertime as being produced for radio in 1969. This is actually a play called Summer, written by the French playwright Romain Weingarten, and translated by Reed. Summer was broadcast on Radio 3 on October 3, 1969.

A typescript for Summer resides in the Richard L. Purdy Collection of Thomas Hardy, in the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts department of Yale University (#809).

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

The Copyright Monographs Database at the U.S. Copyright Office is a collection of records of a variety of works, including monographic literary works, works of the performing and visual arts and sound recordings, and renewals of previously registered works of all classes.

A quick search of the " Books, Music, etc." module for last-name, first-name "reed, henry" brings up 20 records, 16 of which are for our Henry. These include his translations of Ugo Betti ( The Burnt Flower-Bed, Summertime, The Queen and the Rebels, and Crime on Goat Island); Luigi Pirandello's All for the Best; Dino Buzzati's Larger Than Life; Paride Rombi's Perdu and His Father; and Balzac's Père Goriot.

The database also has records for the copyrights of two poems set to music by Sir Arthur Bliss: "The Enchantress" (1951), and "Aubade for Coronation Morning" (1953). "The Enchantress" is a translation of Theocritus's " Second Idyll," while "Aubade" was one of ten modern madrigals commissioned for a concert on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II ( A Garland for the Queen).

For more copyright fun, check out the WATCH project: Writers, Artists and Their Copyright Holders.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

Diehard fans of Joan Plowright (or Natalia Ginzburg) may be interested in these posters offered by the National Theatre Archive. They're from the 1968-69 run of Ginzburg's play, The Advertisement, translated and adapted by Reed. The production was directed by Donald MacKechnie and Sir Laurence Olivier, and starred (besides Dame Joan) Suzanne Vassey, Louise Purnell, Edward Petherbridge, Anna Carteret, and Sir Derek Jacobi.

The National Theatre also has an extensive, searchable catalog of performances and items in their archives.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

In 1933, a small theatre group in Birmingham, England, staged a production of Molière's L'Avare ( The Miser) at the Church House, High Street, Erdington ( pictured here). The company called themselves after the name of the house where they rehearsed: The Highbury Players. They had begun in 1924 as an artistic branch of the local Independent Labour Party, originally meeting to read stage plays aloud, but eventually forming the Highbury Little Theatre.

An excerpt from the book Highbury Little Theatre: A Beginning, written in 1946, describes the early efforts of the organization after their first play in 1925:

In the next twelve years the work undertaken included the following full length plays: Conflict, Much Ado about Nothing, Pygmalion, Heartbreak House, The Show, The Roof, Escape, The Skin Game, A Hundred Years Old, Pleasure Garden, Othello, The Circle of Chalk, The Sleeping Clergyman, and L'Avare in a new English translation by John English and Henry Reed—this was in 1932.

Mr. John English, OBE, one of the original members of the group, would go on to become a trustee of the Highbury Theatre Centre, and would help found the Midland Arts Centre.

There can be little doubt that the Highbury Players' co-translator of Molière's L'Avare was our Henry: the odds of coincidence are just too great. Henry Reed was born and raised in Erdington, was a vocal Socialist, and concentrated on French (and Latin) throughout his education, from King Edward VI Grammar School, all the way through his years at the University at Birmingham, which happen to coincide with the play's production.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

I have a backlog of items to dump into the bibliography. Forests of printouts languish, unindexed. By the time I return to them, I'll have forgotten why I printed them out in the first place. Titles like: Common Ground: An Anthology, The Poem in Question, and Poetry of the Second World War: An International Anthology (all of which reprint "Naming of Parts"); American Women Photographers: A Selected and Annotated Bibliography (lists Rollie McKenna's portrait of Reed); King Edward's School, Birmingham: 1552-1952; John Lehmann: A Tribute; and Twentieth Century Italian Literature in English Translation: An Annotated Bibliography, 1929-1997.

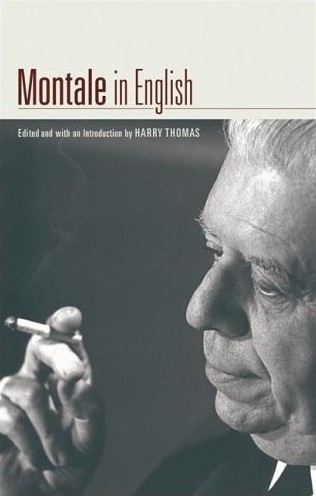

Significantly, there is also Montale in English, the Preface to which contains this lament by the editor, Harry Thomas:

In the end I have decided to include the work of fixty-six translators, but I might have included that of dozens more. The one real regret I have, though, is the absence from this anthology of several translations — Henry Reed's rendering of the great Mottetti, for instance — which repose unprintably in archives.

Thomas is referring to Reed translating into English a series of love song-poems (motets), by the Italian poet Eugenio Montale who, in 1975, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

In his Introduction to the Collected Poems, Stallworthy mentions Reed having "drafted and all but finished polishing" his translation of Montale's Mottetti, but the work never reached publication, and must still be among his papers and notebooks at the University of Birmingham.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

In parsing through the new BBC Programme Catalogue, I've turned up five radio plays Reed translated late in his career. One is later, in fact, than even Reed's reworking of Moby Dick in 1979. And he's credited with none of them in any bibliography I've seen (not even the exhaustive Contemporary Authors entry from 1999). Not surprisingly, the plays are all adaptations from Italian, Reed's adopted mother tongue. Here are the details, in chronological order:

Room for Argument, by Luigi Pirandello. Broadcast on Monday, January 7, 1974 at 8:00 p.m., Radio 4.

Like the Leaves, by Giuseppe Giacosa, broadcast Sunday, May 30, 1976 at 2:30 p.m., on Radio 4. (The Programme Catalogue has Monday, May 24, but the London Times disagrees. Word Aloud also has the 30th.)

The Soul Has Its Rights, by Giuseppe Giacosa. Broadcast on Wednesday, June 22, 1977 at 3:05 p.m., Radio 4.

Duologue, by Natalia Ginzburg, broadcast on Tuesday, September 20, 1977 at 9:30 p.m., Radio 3. (The Catalogue says January 3rd. Duologue is listed in the Sound Archive catalogue, but is undated. I'm double-checking.)

I Married You for Fun ( Ti Ho Sposato per Allegria), by Natalia Ginzburg. Broadcast Monday, January 7, 1980 at 7:45 p.m., on Radio 4, and repeated Saturday, January 12 at 2:30 pm. ( Word Aloud confirms. Also in the Sound Archive catalogue.)

Because I'd never seen these titles before, they stood out like sore thumbs. But I'd say, even if that's all I turn up, the Programme Catalogue has already started earning its keep.

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

Last year, I blogged about a gentleman sharing with me a Hebrew translation of one of Reed's poems. I was attempting to parse the characters back into a webpage, right to left, by hand. I failed miserably!

How do I know this? Because here is Henry Reed's "Judging Distances," translated into Hebrew by the artist, architect, and town planner, Nahoum Cohen.

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

Merhaba! I was startled today, browsing through some old book reviews, to discover that Henry Reed's Collected Poems has been translated into Turkish (Türkçe).

The title is Yıldızlı Şölen, translated by the poet and linguist Coşkun Yerli.

Yerli is a well-renowned translator in Turkey, having taken on the likes of Kobayasi Issa, Matsuo Bashō, Eavan Boland, Roger McGough, Sydney Wade, and James Lovett. He even tackled J.D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye and Nine Stories.

Yerli has also published a collection of his own poetry, Yagmurun Direnisi ("Rain's Resistance"). Here's one of his poems in English, " In a Cloth-Bound Book."

|

1528. Manning, Hugo. "Recent Verse." Books of the Day, Guardian (Manchester), 31 July 1946, 3.

Manning feels that 'Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship.'

|

In the year 1737, upon receiving word of the impending production of a particularly unfavorably satire of the rule of King George II, British Parliament passed the Theatrical Licensing Act, requiring that no person shall for hire, gain or reward, act perform, represent, or cause to be acted, performed or represented any new interlude, tragedy, comedy, opera, play, farce, or other entertainment of the stage, or any part of parts therein; or any new act, scene or other part added to any old interlude, tragedy, comedy, opera, play, farce or other entertainment of the stage, or any new prologue or epilogue, unless a true copy thereof be sent to the Lord Chamberlain of the King's household for the time being, fourteen days at least before the acting.... The Act ( full-text) called for the Lord Chamberlain and his Examiners of Plays to review and, where necessary, censor potential scripts before they reached the stage, with the intent of protecting the corruptible public. At the time, plays were already restricted to performances in theatres which had been granted royal patents. The Patent Act was repealed in 1843, but the Licensing Act remained intact until 1968.

Reed had adapted Ugo Betti's play, Crime on Goat Island, for the BBC's Third Programme in 1956. His translation had already appeared on the stage in 1955, at New York's Fulton Theatre. In 1957, however, a production was planned for the Oxford Playhouse, which ran into a "spot of bother" with the Lord Chamberlain's Office.

A very helpful gentleman at the British Library, Arnold Hunt, emailed me that the Manuscript Collections contain the original typescript submitted for examination (with the famous blue pencil marks of the censors), as well as additional correspondence detailing the debate over Reed's version of Betti's play. Mr. Hunt writes: “On 3 November 1957, the Assistant Examiner, St. Vincent Troubridge [a descendant of Lord Nelson], reported that he was not prepared to recommend the play for licence. 'The story of this play, condensed into a couple of sentences, is that to the widow of a Professor living on a remote goat-farm with her daughter and sister-in-law, there appears an attractive young man, claiming to have been friendly with the Professor in a war-time captivity. He proceeds to have sexual intercourse with all these three closely related women in turn, the widow on the first night of his arrival. A few weeks later they murder him down a well. This to my mind is a great deal too farmyard to be permissible in common decency on the public stage.'” The examiner's synopsis is fair, even if he was taking his responsibilities a bit too seriously (read more about how censorship shaped modern British theatre). The script was eventually deemed "'sordid and revolting,' but not injurious to morals," and the play was granted a license to be performed, hinging on the removal of one passage, which Troubridge described as 'sodomy in reverse, about goats trying to make physical love to their goatherds.' Angelo, the scroundrel of the play, tells a story of how goats in his country sometimes fall in love with their goatherds: And eventually the shepherd begins to understand, and after a little while they... make love, there in the meadows, pressing close together, closer than a man and woman even. (Act I, scene iv.) To the credit of his station, the Lord Chamberlain himself, the Right Honourable Lawrence Roger Lumley, 11th Earl of Scarborough, commented "I don't feel very strongly about the ordinary sex part, but I do draw the line at the goats."

(Coincidentally, the composer Donald Swann, who wrote the music for Reed's Hilda Tablet plays, mentions his regret at never having anything of his banned by Lord Scarborough, whom he called a "charming chap.")

Crime on Goat Island opened in Oxford on December 2nd, 1957. The following day, the Times' special correspondent reported weakness in Betti's plot and doubt in Reed's script: "The jealousy between the three women, the division in the household: these are real enough. But as Betti and his translator Mr. Henry Reed handle them they subtract from the interest of the characters instead of adding to it." No mention is made, however, of lovesick goats (The Arts, 3 December 1957, 3).

A history of censorship and its effects on British theatre was published last year: The Lord Chamberlain Regrets: British Stage Censorship and Readers' Reports from 1824 to 1968 ( Amazon.com US).

|

1527. Rosenthal, M.L. "Experience and Poetry." Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review (New York), 17 October 1948, 28.

Rosenthal says Reed shares with Laurie Lee 'that unhappy vice of young intellectuals—a certain blandness of which the ever-simple irony is a symptom.'

|

I was surprised to find today, at "The Friends of the Library" used book sale, a striking number of sex books. Marital Aid-this, and Human-Sexuality-that. Titles that made me smile, then blush. The Pictoral Book of Sex. Sexercises. I'm the type who flips cautiously through coffeetable art books, lest the pages fall open at a particularly baudy nude by Titian or Botticelli.

When I first walked in, it was obvious the sale was a sort of barely-restrained chaos: a great square of tables, with people circling in both directions. As it was already an hour after opening, I circled left. Logic dictated that most of the herd would automatically turn right, and the less-picked over titles would be in the opposite direction.

There was no attempt at any sort of organization. Books were just randomly laid on the tables in three rows, spines up, with little piled ziggurats bookending the loose ends. At one point, a guy next to me asked if I knew how the books were organized. Alphabetically? By subject? I told him, "The books are arranged... horizontally." As empty spaces appeared in the rows, volunteers would heap more books into the holes like cordwood, from boxes under the tables.

The library's "Friends" get early admittance to these sorts of sales and as a result, by the time I arrived, there were great levees of books stacked against the walls, with slips of paper on top that read, "SOLD." Hoarders and bookdealers were breaking these piles down into boxes to be carted off to compulsive collections, storefronts, and eBay.

The books were a curious amalgam of donations which could not be reckoned within the scope of the library's collection, withdrawn titles, and great masses of texts which must of come directly out of some retiring professor's office. Whole tables of books on the ethics of euthanasia, machine learning, Jewish history, and plays and pulp novels in French.

There also smelled to be a higher-than-average number of Patchouli wearers present at the sale. Why do otherwise-attractive people insist on cloaking themselves in what amounts to the olfactory version of blasting their car stereo? Why are so many of them attracted by the lure of cheap books?

I spent a glorious, contented, three hours at the sale, making two complete passes over the tables, but didn't come away with any treasures. I found a copy of Perrine's Sound and Sense (which I probably already own a copy of). A theatre book of the script for Breaking the Code, by Hugh Whitemore, based on Hodges' book Alan Turning: The Enigma. A paperback on Australian literature, with a chapter on the Ern Malley poems.

My prize was a 1958 Grove Press edition of Three Plays by Ugo Betti, translated by Henry Reed. My heart leapt when I saw Reed's name in bold, white letters on the spine, hiding amidst an ancient pile of German literature in hardcover.

|

1526. Blunden, Edmund. "Poets and Poetry." Bookman, n.s., 1, no. 4 (July 1946): 14-15.

Edmund Blunden says Reed's Lessons of the War poems 'have captured something of the time-spirit and ambiguity of the recent war in a style of wit and deep feeling united.'

|

I've been corresponding with a gentleman in Israel who has taken great care to translate Reed's poem " Judging Distances" into Hebrew. An audacious undertaking!

Having only a tenuous grasp of English myself, and no familiarity with the Semitic languages, I'm attempting to reverse-engineer the HTML generated from a Word document. Right-to-left reading is the least of my problems, and the commas are driving me crazy. Perhaps I may never get the knack.

לא רק באיזה מרחק, הדרך בה אומרים את זה

חשובה מאד. אולי לעולם לא תשלטו

בשיטת אומדן מרחקים, אך לפחות תדעו

איך לדווח צורות נוף: הגזרה המרכזית,

מימין לקשת, ומה שהיה לנו ביום שלישי שעבר,

ולפחות בסוף תדעו

|

1525. "Reed, Henry," Publishers Weekly, 152, no. 15 (11 October 1947), 1945.

A note on the publication of the American edition of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|

Merhaba! I was startled today, browsing through some old book reviews, to discover that Henry Reed's Collected Poems has been translated into Turkish (Türkçe).

Merhaba! I was startled today, browsing through some old book reviews, to discover that Henry Reed's Collected Poems has been translated into Turkish (Türkçe).