|

Clouds Intend

Found in TranslationIn parsing through the new BBC Programme Catalogue, I've turned up five radio plays Reed translated late in his career. One is later, in fact, than even Reed's reworking of Moby Dick in 1979. And he's credited with none of them in any bibliography I've seen (not even the exhaustive Contemporary Authors entry from 1999). Not surprisingly, the plays are all adaptations from Italian, Reed's adopted mother tongue. Here are the details, in chronological order:

Room for Argument, by Luigi Pirandello. Broadcast on Monday, January 7, 1974 at 8:00 p.m., Radio 4. Like the Leaves, by Giuseppe Giacosa, broadcast Sunday, May 30, 1976 at 2:30 p.m., on Radio 4. (The Programme Catalogue has Monday, May 24, but the London Times disagrees. Word Aloud also has the 30th.) The Soul Has Its Rights, by Giuseppe Giacosa. Broadcast on Wednesday, June 22, 1977 at 3:05 p.m., Radio 4. Duologue, by Natalia Ginzburg, broadcast on Tuesday, September 20, 1977 at 9:30 p.m., Radio 3. (The Catalogue says January 3rd. Duologue is listed in the Sound Archive catalogue, but is undated. I'm double-checking.) I Married You for Fun (Ti Ho Sposato per Allegria), by Natalia Ginzburg. Broadcast Monday, January 7, 1980 at 7:45 p.m., on Radio 4, and repeated Saturday, January 12 at 2:30 pm. (Word Aloud confirms. Also in the Sound Archive catalogue.) Because I'd never seen these titles before, they stood out like sore thumbs. But I'd say, even if that's all I turn up, the Programme Catalogue has already started earning its keep.

Insults and Eliot and LearIn 1953, Reed wrote a critique of Eliot's prose as it relates to his verse, called "If and Perhaps and But" (Listener, 18 June 1953, 1017-18). I hadn't realized until today that the title is actually a quote from a self-deprecating poem of Eliot's: "Lines for Cuscuscaraway and Mirza Murad Ali Beg" (part V. of "Five-Finger Lessons," originally published in Criterion 12, no. 47 (January 1933): 220-222).

How unpleasant to meet Mr. Eliot!Apparently, "Cuscuscaraway" and "Mirza Murad Ali Beg" were the names of Eliot's dog and cat (and Mirza Murad Ali Beg was really the author of Lalun the Beragun, a 19th-century work of historical fiction set in India). This is actually Eliot parodying Edward Lear's "How Pleasant to Know Mr. Lear" (Nonsense Songs, 1871), the text of which can be read in this Slate.com article by Robert Pinsky, a "little anthology of poems that deliver insults."

BBC Programme CatalogueThe experimental, prototype BBC Programme Catalogue went live today, and currently contains over 900,000 entries for radio and television programs. This represents only a "sub-set" of the data held by the BBC's Information and Archive Department.

Henry Reed has 77 entries! It's mostly recordings located in the Sound Archive, but there's a lot of metadata that's absolutely priceless. Also, they've have mistakenly concatenated our Henry with that other Henry, a composer and conducter from the 1940s and '50s. How do you straighten that out? Birth and death years in the title field, or descriptors (Author, Composer), at the very least. If you please?

Flowers and WarSeveral weekends ago I made a short excursion up to the state capital, to visit the Richmond Public Library. It was a lazy, rainy Sunday, and I needed, of all things, a 19th-century book on flowers.

The book was the Reverend Hilderic Friend's Flowers and Flower Lore (1883), and I was startled to find that it was not on the shelf. Up and down the folklore section I scanned. A word to the wise scholar: it never hurts to phone ahead. Luckily, a librarian flew to my rescue, advising that their older texts are kept in closed stacks, downstairs in the basement. Whew! I had Friend's beautiful, leather-bound, two-volume set in my hands, momentarily. In the end, I found that they didn't even contain exactly what I was looking for. Such are the perils of blind librarying. I consoled myself by browsing the stacks for poetry, discovering that my Dewey Decimals have become almost irreparably rusty. Poetry: 811, yes. English poetry? 821. Oh. They had several anthologies which I had indexed but never seen: notably, Dylan Thomas's Choice (Maud and Davies, eds. New York: New Directions, 1963). Deep into my Ziploc bag of dimes I dipped, to feed the ravenous Xerox machines. The real boon was a book I had never heard of or seen: War Poetry: An Anthology, edited, and with an introduction and commentaries, by D.L. Jones (1968). This evening, I added Jones' commentary on the Lessons of the War poems to the website. It also happened to be the last day of the Friends of the Library booksale, and from the pillaged remnants I managed to scavenge a small paperback of English translations of the poetry of Leopardi. They wanted 50¢, but I gave them a buck, and told 'em to keep the change.

Surrealism in BirminghamThe artist Conroy Maddox (Guardian obituary) discovered Surrealism in 1935, when he was twenty-two, browsing through a book on European painting in the Birmingham City Library: Wilenski's The Modern Movement in Art (1927, rev. ed. 1935). Maddox had been born in Ledbury, Herefordshire in 1912, but his family settled in Erdington in 1933.

Although he eventually outgrew the city, Maddox was inspired by urban Birmingham—with its libraries, theatres, and art galleries—after a youth spent in the countryside. In his (impeccably illustrated) biography of Maddox, The Scandalous Eye, Silvano Levy quotes generously from conversations and correspondence with the artist. These insights from Maddox provide a context for Henry Reed's social life in Birmingham before the war: During that time, I began to explore the possibilities I discovered in collage which questioned the innocence of all images and the allusiveness of reality. Evenings were spent with in talk with Robert and John Melville, the poet Henry Reed, and Dorothy Baker. On Sundays, we would go to the Film Society and saw for the first time the works of Eisenstein, Cocteau, Pudovkin, Fritz Lang and others. Afterwards, we would talk either about the film or more imaginatively. (p. 45) Reed, of course, was raised in Erdington, and from 1932-1936 he was studying at the University of Birmingham. Robert Melville would later become the art critic for the New Statesman. His brother, John Melville, was an artist also interested in Surrealism, who had occasion to paint a rather more traditional portrait of Reed (popup window). Along with Emmy Bridgwater, William Gear, and Stuart Gilbert, this circle of artists became the Birmingham Group. But Maddox's group of friends and followers was not not limited to painters: The entourage included George Painter, Harry Browne and Philip Troutman, who were literary scholars; Cornelius Russell, an art historian at the university; his wife Jane; Dorothie Hewlett; Edward Lowbry [sic], a microbiologist and poet; Roy Knight, a modern languages academic who had unsuccessfully tried to teach Maddox some French; Dorothy Baker, a writer; and the poet Henry Reed, who, whenever the opportunity arose, would introduce his 'heterosexual friend Conroy Maddox'. (p. 98) Reed's openness (and humor) about his sexuality never ceases to surprise me. This litany of Birmingham's intellectual A-list will keep me busy for weeks, hunting the library stacks for biographies and collected letters, sliding my digitus secundus down the "R" pages of indexes, looking for references to Reed (is that why it's called the "index" finger?). George Painter, the Proust biographer, had attended secondary school with Reed (see previous post). My Granger's Index lists five poems of Edward Lowbury which appear in various anthologies. His poem on the Hiroshima bombing, "August 10th, 1945—The Day After," appears on the Salamander Oasis Trust website. Lowbury's Collected Poems was published in 1993 (Contemporary Review 263, no. 1535 (December 1993): 329-330). The two mentions of Dorothy Baker are especially intriguing, A severely limited preview of Levy's The Scandalous Eye: The Surrealism of Conroy Maddox is available from Google Books (the copyrighted images appear to be restricted). I have a library copy here beside me, and it's a beautiful, glossy-paged book. I'm astute enough (but only just) to detect the influence of Picasso, Magritte, and Dali in Maddox's work, but I fear I have been forever spoiled for his googly-eyed collages by the Spongmonkeys (Flash, audio, weird).

Prizes and AccoladesReed never received a great deal of professional recognition during his lifetime, apart from a few encouraging reviews of his poems and plays, and the inclusion of "Naming of Parts" in whatever edition of a literature anthology was getting published for some university English course. He does proudly list two awards in his autobiographical Who's Who entry (which rather delinquently fails to notice for several years his death in 1986).

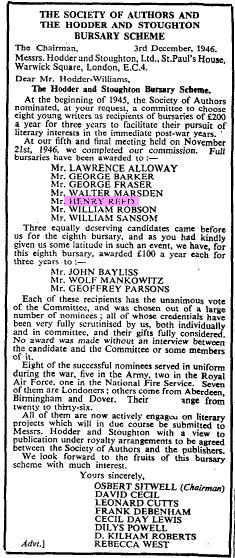

On Sunday evening, March 16, 1952, at 6:00 PM, Reed's radio play, The Streets of Pompeii, premièred on the BBC's Third Programme, featuring the music of Anthony Smith-Masters, and the voice talents of Flora Robson, Marius Goring, and Carleton Hobbes (as the Lizard). Richard Trewin, in his review for the Listener the following Thursday (after a repeat broadcast), had this to say: Henry Reed, summoning atmosphere eagerly, was excited about Pompeii, but he took a long time to fire us. During the first hour of a mixture of this-way-to-the-tomb intensity and cheerful chatter, I felt as if I were walking on a battered and dangerous mosiac pavement. All well for a moment or so; then a trip over a loose tile, and a headlong sprawl. Still, at length, the author (and the producer, Douglas Cleverdon) startled genuinely in a reconstruction of the last hours of Pompeii under that engulfing flood of hot, wet ash. This was a real and terrifying return journey. (Listener 47, no. 1203 (20 March 1952): 487.) Despite this tepid-to-fiery reception, in 1953 The Streets of Pompeii was awarded the Premio della Radio Italiana (the Italia Prize for literary or dramatic programs), by the RAI (Italian radio and television). The awards ceremony was held in Palermo that year, but I have no evidence Reed was in attendance. More than a quarter of century later, in 1979, the Society of Authors selected Reed for its Pye Radio Gold Award, not for a radio broadcast in the preceding year, but for his "outstanding achievement in radio." (Wade, David. Times London, "Out of the Smoke, Into the Sound," 17 November 1979, 13.) The award was in recognition not only for Reed's 1946 radio adaptation of Moby Dick and many dramas set in Italy, but also for his seven-part comic/literary/musical sequence of Hilda Tablet plays. There is a third award which Reed neglects to list. In 1945, a committee was appointed by the Society of Authors to award to eight deserving young authors the Hodder and Stoughton Bursary Scheme—a stipend of £200 a year for three years—in order to "facilitate their pursuit of literary interests in the immediate post-war years." Sitting on the committee were C. Day Lewis and Rebecca West, and it was chaired by Sir Osbert Sitwell. The first two recipients were announced in November, 1945 as Henry Reed and William Robson. The remaining authors were advertised the following year as Lawrence Alloway, George Barker, John Bayliss, George Fraser, Wolf Mankowitz, Walter Marsden, Geoffrey Parsons, and William Sansom (there was a three-way tie for the eighth bursary):  Times (London), 20 December 1946, 6. In a 1946 questionnaire in the journal Horizon, a panel of eminent British authors including Elizabeth Bowen, Robert Graves, and George Orwell were asked, "How much do you think a writer needs to live on?" The consensus seems to be about £1000 a year, which was Reed's answer (although Bowen was more comfortable with £3,500). It's possible Reed didn't feel the generous bursary was worth mentioning by the time he penned his entry for Who's Who, but it would have certainly been welcome in 1945, and undoubtably went great lengths toward encouraging Reed's career as a poet, critic, and playwright.

MagnoliaizedI have a folder in my Firefox bookmarks just for Henry Reed-related webpages. Many of these were imported from IE's favorites when I "upgraded" browsers. Most of them are throwaway hits from brute-force keyword attacks in major search engines: '"henry reed" bbc', '"henry reed" translation', and the like.

Unfortunately, once your bookmark folder exceeds the height of your browser, it becomes less and less managable, until it finally becomes impossible to find anything at all. Especially if you're just lazily dumping in webpages with "Bookmark This Page...", and not bothering to edit the titles or descriptions. For shame. So, onto social bookmarking! I exported my bookmarks to html, and imported them to Ma.gnolia, and spent an hour or so deleting the extraneous, non-Henry, links. Zip zop. What remains needs some pruning and a lot of editing, but here you have them: my Henry Reed bookmarks (with tags!).

A Call to ArmsI was intrigued by mention, in the Wikipedia entry for "War poet," of an editorial which appeared in England before the outbreak of major hostilities during World War II. I looked it up this evening, and found the words still ring soundly true: a rallying cry for poets to champion human experience during troubling times. I reproduce it here, in full, knowing that Reed must have read these very words. From the Times Literary Supplement, 30 December 1939, 755:

TO THE POETS OF 1940 We review in this issue some collected poetry of 1939. What can the poets do with the year 1940, when the world seems to be threatened with a new Dark Age? Of one thing we can be certain: if, shocked by the suffering inflicted by nations in tumult, they fall into resignation or despair, and yearn only for the nothingness where lost man may find "what changeless vague of peace he can," then the Dark Age is assured. And that is true too if they try to make harmonies from hatreds or seek the salvation of man in political formulas labelled Left or Right. This war has followed so close on the heels of the other that it conveys no sense of novelty to awaken the creative spirit. It has the forbidding aspect of an old foe. Consciousness has been struggling vainly to free itself from the mark of the last calamity, but our poetry continued to be permeated, in varying forms and degrees, with the memory and often with the mood of 1914-18. A quarter of a century of moral disquietude and revolt has not been accompanied by any clear conception of what new order should replace the old. Deliberately heedless, even defiant of ancient values, poetry receded and, but for some faithful hands, might have lost itself. It can no longer be argued that these were symptoms of an age of transition; there never was any other kind of age. Here we are faced with an undeniable repetition of history, with nothing original, nothing unique about it. What can the poets make of it in their explorations of reality? Is it possible to find in this convulsion not the cloud of a Dark Age but the dawn of another Renaissance? The prospects are precarious, but not hopeless. The first shock of the war produced a paralysis of the poetical intelligence. Verses turned into tears. But already those who are concerned to keep poetry alive are adding their comment on where the world stands. England was long agonized by the ambitions of a conqueror at the beginning of the last century, which was prematurely outraged like our own. Yet it saw the quickening of a new spirit in English poetry comparable with the splendor of Elizabethan days. It is significant that the seventeenth century, plagued by civil war and religious and intellectual conflicts, also saw an abundant and distinguished poetic achievement in intimate response to the pace of life in days of stress and change. he last Was presented the spectacle of hundreds of young poets, in tune with the national will, first finding voice in the brutal fact that evil things were menacing their heritage. The resultant poetry was in the irony and pity of it, such as Wilfrid Owen's, or in the noble exultation of those who endured hardship and danger for an idea, such as Alan Seegar's [sic]. The same idea is at stake—because the War was not finished. Civilization was granted an uneasy reprieve while the Philistine took breath. He is now reinvigorated and more desperate, and we are feeling the pulse of the same crisis. Clearly wars and revolutions are destroying the old social order of the world. But we need not despair of the birth of a new and finer order. It is for the poets to sound the trumpet call. We see the warning in Germany and Russia of the way the arts decline when the paths of humanity are polluted by the predominance in every department of life of a cheap political idea. In those unhappy lands the creative faculty is extinguished. Here it is still watchful and alert, and it knows that this is its battle, its test. It will draw its spiritual ecstasy from this renewed assault on human dignity. Patriotism alone is not enough; but the promise of a renovated world, saved at last from the jackboots of violence, should be sufficient inspiration. The beauty of the new poetry will be in its integrity; it will be grave, positive and stark, because it is forced to look intently at the worst, but it will relate to the immediate, agonizing facts in universal terms. It may even find a programme for this immediacy. Poetry and religion have an eternal alliance, though for too long it has been unacknowledged. Religion is an organizing force with an intensity of purpose more clarifying and constructive than human reason, which in these sad days is suspect. Poetry, "the breath and finer spirit of all knowledge," hand in hand with religion can exercise a magnetism to keep hope alive and in movement. The monstrous threat to belief and freedom which we are fighting should urge new psalmists to fresh songs of deliverance. Update: More on the Times Literary Supplement's role in wartime England is available at the TLS Centenary Archive. (Thanks, Bruce!)

Henry Reed Hates to SeeIn the tradition of McSweeney's lists:

---- PEOPLE HENRY REED HATES TO SEE IN INDEXES HE HIMSELF IS NOT LISTED IN. ---- Green, Henry

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||