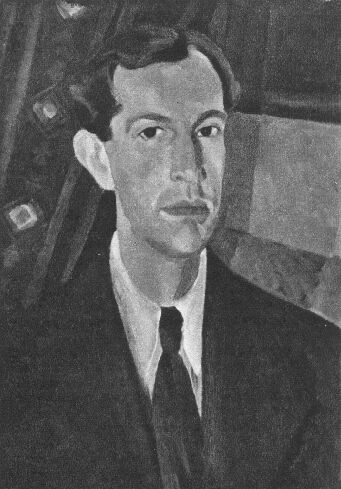

Logically, the portrait was created prior to 1946. A potential clue to its genesis appears in Reed's 1954 radio play, The Private Life of Hilda Tablet. During the course of the play, the renowned composeress Hilda Tablet directs the narrator, "Herbert Reeve" (wink, wink), to interview a friend and artist, affectionately called "Bunny":

Hilda: R. Egerton Bunningfield, ARA. He painted a damn good portrait of me in 1943.

(fade chords behind Mr Bunningfield. He seems rather weighed

down by unsuccess)

Bunningfield: Well, yes, the picture has been much admired, and it was very good of Miss Tablet to sit for it. I asked her to, you know. It was meant to be one of a series of great women of the time, their part in the war effort. Naturally, I wasn't quite prepared for quite all the conditions Miss Tablet imposed. I wanted her to be playing an instrument, of course, but what I had in mind was a clavichord or the like, with highlights on a brocade dress and so on. I never imagined she would insist on the instrument being a bugle, though I agree it was appropriate to a picture illustrating the war effort and that. And she also insisted on it being an open-air composition; that's the whole of the Pennine Chain in the background... And quite frankly, Mr Reeve, she's the kind of figure I really would have preferred to have painted draped... but no, she insisted...

(fade last words behind chords)

(fade chords behind Mr Bunningfield. He seems rather weighed

down by unsuccess)

Bunningfield: Well, yes, the picture has been much admired, and it was very good of Miss Tablet to sit for it. I asked her to, you know. It was meant to be one of a series of great women of the time, their part in the war effort. Naturally, I wasn't quite prepared for quite all the conditions Miss Tablet imposed. I wanted her to be playing an instrument, of course, but what I had in mind was a clavichord or the like, with highlights on a brocade dress and so on. I never imagined she would insist on the instrument being a bugle, though I agree it was appropriate to a picture illustrating the war effort and that. And she also insisted on it being an open-air composition; that's the whole of the Pennine Chain in the background... And quite frankly, Mr Reeve, she's the kind of figure I really would have preferred to have painted draped... but no, she insisted...

(fade last words behind chords)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Plays for Radio (1971), p. 70

Is the character Bunningfield an homage to Reed's Birmingham chum? Did Melville ask Reed to sit for him in 1943, as part of series of wartime portraits of Birmingham notables? It's difficult to know for sure which details of the radio plays are lifted entirely from Reed's life. The mention of the Pennines is intriguing as well, since it places the fictional painter in northern England (not terribly far north of Birmingham). All this is speculation, of course, and I could be wrong as wrong.

I got to thinking about Reed's misplaced portrait this evening, after learning that the BBC announced today a commitment to digitize all 200,000 of Britain's oil paintings in public ownership, and have them available online by 2012. More information on the effort, and the BBC's "deeper commitment to arts and music," at the Guardian.