|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from February 2007

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

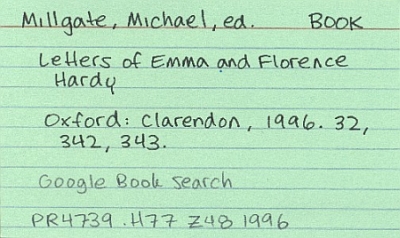

Here's how it goes: I'm sifting through Google Book Search or Amazon's Search Inside the Book, and a reference to Henry Reed materializes out of the ether: maybe a footnoted quotation, or just a passing comparison to another poet. If it's something Reed himself wrote, I can usually recognize it by name. I'll check the bibliography online, and if the article or book doesn't already appear, I'll e-mail myself a link or the pertinent information. Later, I'll pull out my portable, plastic card file and fill out a new index card. I'm using colored cards to indicate items that I don't own.

From Richard Altick's excellent and invaluable The Art of Literary Research (1963), the chapter entitled, "Making Notes":

For every book and article you consult, make out a bibliographical (three-by-five) slip. If your project is a fairly modest one, to be finished in one or two months' time, before your memory starts to fail, this point is not so important; in such a case, modify the rule to read "for every book and article in which you find information." But if you are working on a dissertation or book, it is extremely useful to keep a record of every source you examine, whether or not you take anything from it. A few months later, running across a reference to a certain article that sounds as if it might be valuable, you may forget whether or not you looked at it. Quick recourse to your file of bibliographical slips may save you, at the very least, the labor of hunting it down again in the library and, often, the trouble of re-reading it.

On the face of the bibliographical slip, copy the author, title, edition (if any is specified), place and date of publication, and (if it is a fairly recent book) the publisher. Or, if it is an article you are recording, note the author, title, periodical, volume number, year, and pagination. Always take this information from the source itself as it lies before you, never from any reference in a bibliography or someone else's footnote. Authors' initials and the exact spelling of their names, the titles of books and articles, and dates have a way of getting twisted in secondary sources. Play safe by getting your data from the original, and doubly safe by re-checking once you have copied down the information. On the face of the same slip—I use the bottom lefthand corner—record the call number of the book or periodical, and if it is shelved anywhere but in the main stacks of the library, add its location. If you have used the item at a library other than your headquarters, record that fact too ("Harvard," "Newberry," "Stanford"). These are small devices, seemingly unimportant, but in the aggregate they are tremendous timesavers if you are dealing with hundreds of sources and the storage space in your brain is reserved, as it should be, for more vital matters.

On the back of the bibliographical slip, I usually write a phrase or even a short paragraph of description and evaluation, again to refresh my memory two or three years after I have used the book. Since nobody sees these slips but me, I am as candid, peevish, scornful, or downright slanderous as I wish; if a book is bad, I record exactly what its defects are, so that I will not refer to it again or, if I have to do so, in order that I will remember to use it with extreme caution. If, on the other hand, it is a valuable book, I note its outstanding features. And I also record just what, if anything, it has contributed to the study on which I am engaged. Perhaps I also leave a memo to myself to re-read or re-check certain portions of it at a later stage of research, when conceivably it will provide me with further data that at this point I do not anticipate I shall need. Finally—and this is particularly recommended to students whose research requires them to scan large quantities of dull material, such as rambling four-volume Victorian literary reminiscences—I note the degree of exhaustiveness with which I inspected the item, by some such phrase as "read page by page" or "thoroughly checked index." Similarly, I recommend that you make a slip for every bibliography you have consulted, so that you can be sure you have not inadvertently overlooked it.

If it is one of the serial bibliographies of literary scholarship, such as the annual bibliography of studies in romanticism, record the precise span of years you've covered. If it is a subject bibliography, such as Poole's Index, list the individual entries under which you have looked ("Education," "Literature," "Reading") in case other possibilities occur to you later on. Once again, the whole idea is to save wasteful duplication of effort. Three or four minutes spent in making such a slip can save a whole day's work a year or two later.

For more on creating bibliography cards for a research project, here's an online style manual.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

A heartbreaking turn of events appeared this evening, in Michael Millgate's Letters of Emma and Florence Hardy (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996). In a letter dated December 7, 1936, Florence Hardy (then aged 57) mentions 'A young man from one of the universities visiting me a few weeks ago said that all the stories one heard were amusing yet the time might come when the nation would be tired of a comic Royal Family.' Millgate notes this "young man" was none other than Henry Reed. In 1936, Reed had graduated with an MA from the University of Birmingham, and he was compiling material and interviewing contemporaries for his planned biography of Thomas Hardy.

Later, Millgate produces a letter to Reed from Florence Hardy: To Henry Reed

max gate, | dorchester, | dorset.

25th Dec. (1936)

Dear Mr. Reed,

I have been thinking very long & seriously about the book we discussed when you were here, and the more I think about it the more impossible it seems. My own memory is not good & becomes worse & worse, & probably I have exaggerated in my own mind much that was told me, &, as for Miss [Katherine "Kate"] Hardy, she is an old lady in bad health, who has, during the last days lost her nearest surviving relative [cousin Polly Antell] & she will not see any stranger, nor will the doctor allow her her to do so. Moreover she would refuse to discuss any member of her family with anyone. It is possible that I built up a great deal on a few careless remarks from prejudiced persons. I should be very sorry to put into print more than is in my biography as there is not a scrap of documentary evidence to go upon.

Also, with regard to a stage version of 'The Dynasts'—I find that my husband left very special instructions about that, & any performance by amateurs, except the O.U.D.S [Oxford University Dramatic Society], is prohibited. I am sorry to be so negative on both these points, but I hope you will understand.

With seasonable wishes,

Yours sincerely,

Florence Hardy.

Reed's literary hopes and dreams were swept away in the span of two small paragraphs. According to Millgate's notes, the project Florence deems "impossible" was a biography of Thomas Hardy which Reed had suggested, to be based on his conversations with Florence and Hardy's cousin Kate. And apparently Reed was also hoping to adapt Hardy's epic verse-drama on the Napoleonic Wars, "The Dynasts," into a stage play, perhaps for the Highbury Little Theatre group, in Birmingham.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

One of the odd, esoteric things to the study of Henry Reed is becoming familiar with the arms of World War II and their proper use. For instance, when Reed writes to his sister, in 1941, that he is learning to manage an anti-tank rifle, it is helpful to know that he is talking about the " Boyes" anti-tank rifle (though not particularly useful).

Now, I am not a gun person. Far from it. I know less about firearms than I do about automobiles. Or women, for that matter. Nevertheless, I enjoy watching endless Second World War documentaries on the History Channel, and I'm always intrigued by any details of 1940s-era basic training which may have inspired Reed's "Lessons of the War." Which is why I was so happy to see this recent " Piling Swivel" thread in the Great War Forum, which discusses piling of arms, and includes step-by-step illustrations:

Also, I stumbled across this compilation of old British Pathe newsreels on YouTube, which opens with a demonstration of rifle training with the Pattern 1914 Lee-Enfield, and mentions not only "easing the spring," but even "judging distances."

The other tangential area to studying Reed is the realm of WWII cryptography, and that gets even more weird and esoteric. Oh, and japonica: I know waaaay too much about japonica.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

Almost a year ago, I mentioned a quote I couldn't place. In Shire's British Poetry of the Second World War, the chapter "Where Are the War Poets?" opens with the epigraph, 'To fight without hope is to fight without grace.' The quote is attributed to Henry Reed, but I haven't (yet) found where he may have written the line. I'm beginning to suspect it may lie in one of the two "Poetry in War Time" articles Reed wrote for the Listener in 1945, and which I haven't seen. (Then there's this strange anomoly.)

I do, however, know the origin of the phrase. If the words are truly Reed's, they were a response to his epony-nemesis, Herbert Read. Read's most famous poem of World War II is " To a Conscript of 1940," in which a veteran of the First World War addresses a new recruit:

'... There are heroes who have heard the rally and have seen

The glitter of garland round their head.

Theirs is the hollow victory. They are deceived.

But you my brother and my ghost, if you can go

Knowing that there is no reward, no certain use

In all your sacrifice, then honour is reprieved.

To fight without hope is to fight with grace,

The self reconstructed, the false heart repaired.' This is not exactly the sentiment of Rupert Brooke, but Reed (as a conscript of 1941) would still have certainly been in some disagreement, even though the war, for him, was little more than a terrible personal inconvenience.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

Reed's freelance career with the BBC was more or less over before the demise of the Third Programme in 1970, and he would produce only a handful of translations for broadcast in the following years. Part of the problem was his reluctance, or inability, to adapt to the new medium of television. He had a disastrous experience working with the director Ken Russell on a film about the composer Richard Strauss in 1969-70. This is widely regarded as Reed's only foray into television.

I found a surprising story today in Sean Day-Lewis's memoir of his father, C. Day-Lewis: An English Literary Life (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980), which proves Reed dared to delve into television at least one time, previously. In 1963, Reed had a run-in in Dorset with his friend and fellow poet Cecil Day-Lewis, when both men were working on rival Thomas Hardy projects for TV:

Earlier that summer Cecil had done his work as commentator on a short film about Thomas Hardy made by David Jones for the bbc Television arts programme Monitor. He had said some of his piece at the Upper Bockhampton cottage, near Dorchester, where Hardy was born in 1840. By chance, the poet Henry Reed, the source of so many of the jokes on which Cecil dined out, was at the same time making a Hardy programme for Southern Television. Between them they built this coincidence up into a hilarious anecdote which had the lane jammed with outside broadcasting units, a sea of crossed wires and cross technicians, and the two poets shouting infuriated insults to each other, Cecil ponitificating indoors, and Reed holding forth in the garden. Whatever the difficulties, the bbc film was completed and broadcast at the end of November (p. 254).

Can't you hear the two men pouring derision at each other, playing it up for the cameras and crew? "Day-Lewis, you hack! Are you going to spend all day in there?" "We'll be through when we're through, Reed! You has-been!" That's a lovely compliment about Day-Lewis retelling Reed's jokes, too.

And here's a bit of film-and-tv trivia for you: the actress Kika Markham played Tess in the BBC's film (click on "reveal extra detail"). I recognize her from her cameo as Sean Connery's wife in the 1981 movie, Outland.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

Armstrong, Martin. "The Spoken Word." Critic on the Hearth. Review of Noises, by Henry Reed. Listener 36, no. 933 (28 November 1946): 767.

Baker, Kenneth, ed. Unauthorized Versions: Poems and Their Parodies. London: Faber and Faber, 1990.

Bridson, D.G. The Christmas Child. London: Falcon, 1950. 10.

Carpenter, Humphrey. The Envy of the World: Fifty Years of the BBC Third Programme and Radio 3, 1946-1996. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1996.

Cox, Michael, ed. "Reed, Henry." A Dictionary of Writers and Their Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Feinstein, Herbert. Review of Three Plays by Ugo Betti, translated by Henry Reed. Prairie Schooner 35, no. 2 (June 1961): 180-182.

Hamilton, Ian. "The Forties II." London Magazine 4, no. 3 (June 1964): 67-71.

Heppenstall, Rayner. Portrait of the Artist As a Professional Man. London: Peter Owen, 1969.

Jones, David. Letter to the editor. Listener 50, no 1270 (2 July 1953): 22.

Kenner, Hugh. The Invisible Poet: T.S. Eliot. London: Methuen, 1965. 268.

Korte, Barbara, Ralf Schneider, and Stephanie Lethbridge, eds. Anthologies of British Poetry: Critical Perspectives from Literary and Cultural Studies.

Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2000.

Lehmann, John, comp. Poems from New Writing, 1936-1946. London, 1946.

Ling, Peter, comp. Gentlemen at Arms: Portraits of Soldiers in Fact and Fiction, in Peace and War. London: Owen, 1969.

Magalaner, Marvin, and Richard M. Kain. Joyce: The Man, The Work, the Reputation. New York: New York University Press, 1956. 349.

Pascoe, David. "The Hollow Men." Oxford Poetry 6, no. 2 (Winter 1991).

Radio Times, ( The Primal Scene, As It Were), 7 March 1958.

Radio Times, "Studies of the Italian Poet," 27 May 1949.

Redlich, Hans F. Letter to the editor (Monteverdi). New Statesman and Nation 35, no. 882 (31 January 1948): 94.

Reed, Henry. (Article on W.H. Auden's poetry). The Mermaid (University of Birmingham student magazine) 1932-36?

Reed, Henry. "Autumn Books." Review of Some Recollections, by Emma Hardy. Listener 66, no. 1700 (26 October 1961): 678.

Reed, Henry. Book review. Listener (3 October 1946).

Reed, Henry. "The Builders." Listener 22, no. 549 (20 July 1939): 143.

Reed, Henry. "Christmas Books." Listener 34, no. 882 (6 December 1945): 669.

Reed, Henry. "Correspondence." Listener 33, no. 840 (15 February 1945): 185.

Reed, Henry. "Correspondence." Listener 33, no. 843 (8 March 1945): 271.

Reed, Henry. "The Door and the Window." Listener 32, no. 825 (2 November 1944):

488.

Reed, Henry. ( The Great Desire I Had). Radio Times (24 October 1952): 7.

Reed, Henry. "Iseult Blaunchesmains." Listener 30, no. 781 (30 December 1943): 756.

Reed, Henry. Letter to the editor. Listener 40, no. 1028 (7 October 1948): 529.

Reed, Henry. "Max Gate: Memories of Hardy's Home." Birmingham Post, 15 June 1938.

Reed, Henry. "Morning." Listener 32, no. 811 (27 July 1944): 96.

Reed, Henry. "New Novels." Listener 36, no. 928 (24 October 1946): 570.

Reed, Henry. "New Novels." Listener 36, no. 930 (7 November 1946): 644.

Reed, Henry. "New Novels." Listener 36, no. 933 (28 November 1946): 766.

Reed, Henry. "New Novels." Listener 36, no. 935 (12 December 1946): 856.

Reed, Henry. "New Novels." Listener 37, no. 938 (2 January 1947): 36.

Reed, Henry. "New Novels." Review of Dangling Man, by Saul Bellow. Listener 37, no. 940 (16 January 1947): 124.

Reed, Henry. "New Novels." Listener 37, no. 395 (6 March 1947): 344.

Reed, Henry. "Poem." Listener 18, no. 468 (29 December 1937): 1416.

Reed, Henry. "Poem." Listener 22, no. 556 (7 September 1939): 486.

Reed, Henry. "Poem." Listener 23, no. 587 (11 April 1940): 750.

Reed, Henry. "Poetry in Wartime I: The Older Poets." Listener 33, no. 836 (18 January 1945): 69.

Reed, Henry. "Poetry in Wartime II: The Younger Poets." Listener 33, no. 837 (25 January 1945): 100-101.

Reed, Henry. "The Return." Listener (28 December 1944).

Reed, Henry. Review of A Poet's War: British Poets and the Spanish Civil War, by Hugh D. Ford. Sunday Times (London), 5 September 1965, 39.

Reed, Henry. Review of Expositions and Developments, by Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft. Sunday Telegraph, (pre-June 7) 1962.

Reed, Henry. Review of Four Quartets, by T.S. Eliot. Time and Tide (9 December 1944).

Reed, Henry. "Sonnet." Listener 36, no. 927 (17 October 1946): 498.

Reed, Henry. "South." Listener 19, no. 438 (13 April 1938): 806.

Reed, Henry. ( The Streets of Pompeii). Radio Times (14 March 1952): 11.

Reed, Henry. "Tintagel." Listener 28, no. 720 (29 October 1942): 564.

Reed, Henry. "Travel Books." Listener 65, no. 1659 (12 January 1961): 91.

Reed, Henry. "Two Novels." Reviews of All Hallow's Eve by Charles Williams, and The Only Door Out by Mary Wilkes. New Statesman and Nation 29, no. 733 (10 March 1945): 160.

Reed, Henry. "What the Wireless Can Do for Literature." BBC Quarterly 3 (1948-1949): 217-219.

Rodman, Selden. "Albion's New Versifiers." Review of The New British Poets, edited by Kenneth Rexroth. New York Times Book Review, 19 December 1948, 4.

Scott, John. "Three Plays by Ugo Betti." Italian Quarterly, 1958: 72-74.

Sinclair, Andrew. War Like a Wasp: The Lost Decade of the 'Forties. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1989. 45, 69, 79, 94, 107, 109, 111, 114, 218, 219, 297, 301, 302, 316.

Sinfield, Alan, ed. Society and Literature, 1945-1970. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1983. 160.

Sissons, Michael, and Philip French, eds. Age of Austerity. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1963. 224.

St. John, Christopher. Ethel Smyth: A Biography. London: Longmans, 1959. 250-255.

Suttor, T.L. Review of The Novel Since 1939, by Henry Reed. Southerly 9, no. 4 (1948): 231-232.

Temple, Ruth Zabriskie, Martin Tucker, and Rita Stein, comps. Vol 3, Modern British Literature. New York, F. Unger: 1966.

Val Baker, Denys, ed. Little Reviews Anthology. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1946.

* Citations may be vague. Pagination is approximate. May or may not actually contain a reference to Mr. Reed. More available in the full bibliography.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

The website of one of my favorite books of poetry to browse on rainy days (and least favorite to try and lug around), The Norton Anthology of English Literature, has a few dozen audio samples of poets reading from from their own work, and others'.

The 20th century is represented by poets like W.H. Auden ("Musee des Beaux Arts"), Eavan Boland ("That the Science of Cartography Is Limited"), Ted Hughes ("Pike"), Philip Larkin ("Aubade"), Edith Sitwell ("Still Falls the Rain"), and Dylan Thomas ("Poem in October").

There are also examples of poems from other periods to have a listen to, including the Middle Ages (Seamus Heaney reading from Beowulf), the 16th and early 17th centuries, the Restoration and 18th century Romantics, and the Victorians.

While I'm at it, check out this page of poems at the BBC: Poetry Outloud.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

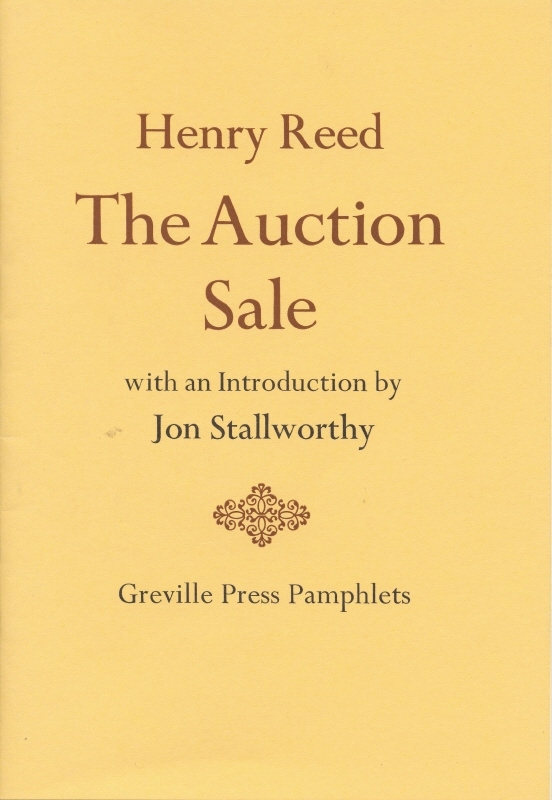

"The Auction Sale," according to Professor Jon Stallworthy, is Henry Reed's 'most ambitious exploration of the landscape of desire' (Introduction to the Collected Poems, 1991). It was written in 1956, and first published in the journal Encounter, in October, 1958. It's a long poem—in excess of 300 lines—in the vein of Thomas Hardy. Set in Dorset at a country auction, it concerns a rousing bidding war over a painting, 'told in a voice as flat as if the speaker were reading from a country newspaper' (Hardy collected local newspaper stories as sources of inspiration):

The auctioneer again looked round

And smiled uneasily at friends,

And said: "Well, friends, I have to say

Something I have not said to-day:

There's a reserve upon this number.

It is a picture which though unsigned

Is thought to be of a superior kind,

So I am sure you gentlemen will not mind

If I tell you at once before we start

That what I have been asked to say

Is, as I have said, to say:

There's a reserve upon this number." In Reed's trademark technique of pitting two duelling voices against each other, the grey November setting and flat repetition of the auctioneer stand in stark contrast to the lyricism of a mysterious bidder's desire for a classical painting:

Effulgent in the Paduan air,

Ardent to yield the Venus lay

Naked upon the sunwarmed earth.

Bronze and bright and crisp her hair,

By the right hand of Mars caressed,

Who sunk beside her on his knee,

His mouth towards her mouth inclined,

His left hand near her silken breast.

Flowers about them sprang and twined,

Accomplished Cupids leaped and sported,

And three, with dimpled arms enlaced

And brimming gaze of stifled mirth,

Looked wisely on at Mars's nape,

While others played with horns and pikes,

Or smaller objects of like shape. Although "Naming of Parts" will always be my favorite, the supreme story-telling and quiet emotion of "The Auction Sale" lends it a special place in my pantheon of Reed's poems. I still remember, clearly, the day I first came across it, collected in Untermeyer's Modern British Poetry at my public library. An undiscovered poem. I recited the whole thing from my wrinkled and well-read photocopy at a local poetry reading, when I had nothing new of my own to share. (I think my interpretation put the crowd at the Daily Grind to sleep that night, despite the legal addictive stimulants. Did I mention it's like, 300 lines long?)

The Auction Sale was published in 2006 as a Greville Press pamphlet. The Greville Press was founded in 1979 by Anthony Astbury and Geoffrey Godbert, with the "enthusiastic support" of Harold Pinter, and the imprint has published the poetry of George Barker, David Gascoyne, W.S. Graham, Edna O'Brien, C.H. Sisson, and David Wright, among others. This collectible edition of Reed's poem includes a critical and biographical introduction by Jon Stallworthy (edited slightly from his Introduction to the Collected Poems).

You can order a copy through Amazon UK, or, if you're feeling adventurous, I have an extra copy to trade. Come back and visit again, for more details. (Bookmark this site: CTRL-D).

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

I've been trying to tidy up around here: index cards have begat unsorted piles out-of-boxes; Xeroxes are backing up into heaps the cat perches upon, unstapled and unread; and I've been neglectful in answering Reed-mail. One of these days I gotta get myself organizized.

Long, cathartic hike to the library today, which paid off in several citations to track down. The university library is about three miles' worth of sidewalk away, on the other side of a good-sized hollow, down and up again. My path crosses the edge of a small lake, and there are herons, ducks, and sometimes even a bald eagle. Bonus points today for taking a side-trip to the bookstore for coffee, an extra two miles. (I'm working at getting over my irrational fear of ordering frou-frou espresso drinks from cafe baristas.)

Today's agenda was to read a bit on British poetry movements from the first half of the twentieth-century. Reed defies classification, and doesn't usually get grouped with anyone except "Poets of the Second World War." Browsing, I found a book on war poetry called Spirit Above Wars (Macmillan Company of India, 1975), by A. Banerjee. The title is taken from a 1917 letter Robert Graves wrote to Wilfred Owen:

For God's sake cheer up and write more optimistically—The war's not ended yet but a poet should have a spirit above wars.

A general chapter on the poetry of World War II brings up, once again, the question which was asked many times from 1939 to 1945: "Where are the war poets?" (see " A Call to Arms", previously). Cited are several articles: "Where Are Our War Poets?" ( Horizon, January 1941), "War and the Poet," by W.D. Thomas ( Listener, 1 May 1941), and Stephen Spender's and Robert Graves' thoughts on "War Poetry in this War" ( Listener, 16 and 23 October 1941). Reed is referenced as having attempted to answer the question before the war's end, in a set of two articles written for The Listener: "Poetry in Wartime: The Older Poets," and "Poetry in Wartime: The Younger Poets" (18 and 25 January 1945).

The Horizon, Spender, and Graves are articles are exciting, but the best part is a quote from a letter to the editor in response to Reed's "Poetry in Wartime" essays, which highlights the contention about the differences between the poems of the First and Second World Wars:

When Henry Reed [....] picked out men like Vernon Watkins, Alun Lewis and Sidney Keyes as the significant poets who had emerged since the start of the Second World War, one correspondent asked, in earnest solemnity:

Now I would like to ask, in a purely scientific-objective spirit, whether there is a single four-line sequence (leave alone an entire short poem) to the credit of any of the poets mentioned by Mr. Reed which has in the same way struck the popular imagination and become property, as did, say, several poems of Rupert Brooke on publication? To this Henry Reed made the blunt rejoinder that Rupert Brooke 'was a poet for the thoughtless; and there is no fundamental difference between his war poetry and the present-day song beginning " There'll always be an England"'.

Oh, schnap! The correct answer to the correspondent's question is, of course: "Today we have naming of parts...." The letter to the editor appears in the February 1, 1945 Listener, and Reed's retort is in the issue of February 15. Two more index cards for the pile, another batch of Xeroxes for the cat to perch on.

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|