|

Japanese Index Card Pr0n

How to Make Bibliography CardsHere's how it goes: I'm sifting through Google Book Search or Amazon's Search Inside the Book, and a reference to Henry Reed materializes out of the ether: maybe a footnoted quotation, or just a passing comparison to another poet. If it's something Reed himself wrote, I can usually recognize it by name. I'll check the bibliography online, and if the article or book doesn't already appear, I'll e-mail myself a link or the pertinent information. Later, I'll pull out my portable, plastic card file and fill out a new index card. I'm using colored cards to indicate items that I don't own.

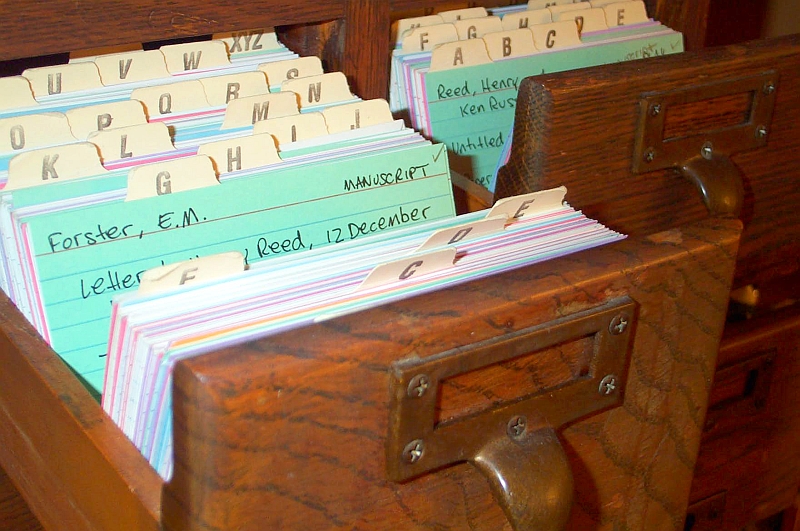

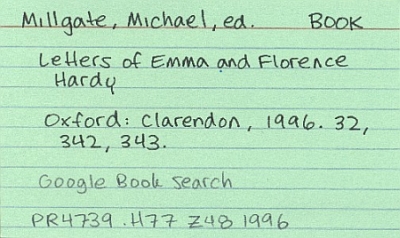

From Richard Altick's excellent and invaluable The Art of Literary Research (1963), the chapter entitled, "Making Notes": For every book and article you consult, make out a bibliographical (three-by-five) slip. If your project is a fairly modest one, to be finished in one or two months' time, before your memory starts to fail, this point is not so important; in such a case, modify the rule to read "for every book and article in which you find information." But if you are working on a dissertation or book, it is extremely useful to keep a record of every source you examine, whether or not you take anything from it. A few months later, running across a reference to a certain article that sounds as if it might be valuable, you may forget whether or not you looked at it. Quick recourse to your file of bibliographical slips may save you, at the very least, the labor of hunting it down again in the library and, often, the trouble of re-reading it. On the face of the bibliographical slip, copy the author, title, edition (if any is specified), place and date of publication, and (if it is a fairly recent book) the publisher. Or, if it is an article you are recording, note the author, title, periodical, volume number, year, and pagination. Always take this information from the source itself as it lies before you, never from any reference in a bibliography or someone else's footnote. Authors' initials and the exact spelling of their names, the titles of books and articles, and dates have a way of getting twisted in secondary sources. Play safe by getting your data from the original, and doubly safe by re-checking once you have copied down the information. On the face of the same slip—I use the bottom lefthand corner—record the call number of the book or periodical, and if it is shelved anywhere but in the main stacks of the library, add its location. If you have used the item at a library other than your headquarters, record that fact too ("Harvard," "Newberry," "Stanford"). These are small devices, seemingly unimportant, but in the aggregate they are tremendous timesavers if you are dealing with hundreds of sources and the storage space in your brain is reserved, as it should be, for more vital matters. On the back of the bibliographical slip, I usually write a phrase or even a short paragraph of description and evaluation, again to refresh my memory two or three years after I have used the book. Since nobody sees these slips but me, I am as candid, peevish, scornful, or downright slanderous as I wish; if a book is bad, I record exactly what its defects are, so that I will not refer to it again or, if I have to do so, in order that I will remember to use it with extreme caution. If, on the other hand, it is a valuable book, I note its outstanding features. And I also record just what, if anything, it has contributed to the study on which I am engaged. Perhaps I also leave a memo to myself to re-read or re-check certain portions of it at a later stage of research, when conceivably it will provide me with further data that at this point I do not anticipate I shall need. Finally—and this is particularly recommended to students whose research requires them to scan large quantities of dull material, such as rambling four-volume Victorian literary reminiscences—I note the degree of exhaustiveness with which I inspected the item, by some such phrase as "read page by page" or "thoroughly checked index." Similarly, I recommend that you make a slip for every bibliography you have consulted, so that you can be sure you have not inadvertently overlooked it. If it is one of the serial bibliographies of literary scholarship, such as the annual bibliography of studies in romanticism, record the precise span of years you've covered. If it is a subject bibliography, such as Poole's Index, list the individual entries under which you have looked ("Education," "Literature," "Reading") in case other possibilities occur to you later on. Once again, the whole idea is to save wasteful duplication of effort. Three or four minutes spent in making such a slip can save a whole day's work a year or two later. For more on creating bibliography cards for a research project, here's an online style manual.

Possession and the Power of Index CardsI dug through my bookshelves tonight, hunting for my copy of A.S. Byatt's Possession. Ah, here it is: the trade paperback from before the (regretable) film version was released. I've read it twice, and the spine is creased and the corners dulled. When I first read the book, straight through in about two days, I was sure it was a masterpiece (despite the sometimes tedious Victorian verse). On second reading, I was dismayed that it didn't quite captivate me in the same way, and I attributed the discrepancy to my own deprivations the first time around.

It was Possession which originally inspired me to begin organizing the bibliography, first with 3x5 index cards, and then in a database. The obsessed scholars in the novel all keep detailed card indexes, in which they transcribe, outline, and keep track of the minute facts of the lives of their respective authors. Here is a scene between Roland Michell, a research assistant working for the editor of the collected papers of the (fictitious) poet, Randolph Henry Ash, and Beatrice Nest, gatekeeper to the journals of the poet's wife, Ellen Ash: Could I see your card index, Beatrice?" "Oh, I don't know, it's all a bit of a muddle, I have my own system, you know, Roland, for recording things, I think I'd better look myself, I can better understand my own hieroglyphics." She put on her reading glasses, which dangled over her embarrassment on a gilt-beaded chain. Now she could not see Roland at all, a state of affairs she marginally preferred, since she saw all male members of her quondam department as persecutors, and was unaware that Roland's own position there was precarious, that he hardly qualified as a full-blooded departmental male. She began to move things across her desk, a heavy wooden-handled knitting bag, several greying parcels of unopened books. There was a whole barbican of index boxes, thick with dust and scuffed with age, which she ruffled in interminably, talking to herself. "No, that one's chronological, no, that's only the reading habits, no that one's to do with the running of the house. Where's the master-box now? It's not complete for all notebooks you must understand. I've indexed some but not all, there is so much, I've had to divide it chronologically and under headings, here's the Calverley family, that won't do... now this might be it.... "Nothing under La Motte. No, wait a minute. Here. A cross-reference. We need the reading box. It's very theological, the reading box. It appears"—she drew out a dog-eared yellowing card, the ink blurring into its fuzzy surface—"it appears she read The Fairy Melusina, in 1872." She replaced the card in its box, and settled back in her chair, looking across at Roland with the same obfuscating comfortable smile. There you have it: the entirety of my formal training in literary research. I was brought back to Possession this evening by stumbling across Pile of Indexcards, which lovingly blogs, in painstaking detail, a similar system of organization. Indexcard + Tagging + Chronological order = "Indexcarding". Accompanied by a terrific photoset on Flickr. I particularly like the tagging and starring methods.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||