|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Letters"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

In 1966, when she was Visiting Professor of English at the University of Washington, Seattle, Elizabeth Bishop wrote to Howard Moss at The New Yorker to let him know she had thrown his hat into the ring to replace her. A respected poet and critic, Moss was The New Yorker's poetry editor for almost forty years, from 1950 until his death in 1987.

This is a great letter in that Bishop gives all the details of the professorship that both she and Henry Reed held: salary and responsibilities (previously a Visiting Professor, Reed had returned to UW as Lecturer in English). The letter appears in Elizabeth Bishop and The New Yorker: The Complete Correspondence, edited by Joelle Biele (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

The letter is dated February 22, 1966: it was Reed's fifty-second birthday. 'I think he is a beautiful poet, don't you?' Bishop writes.

4135 Brooklyn Avenue NE

Seattle, Washington

February 22, 1966

Dear Howard:

Happy George Washington's birthday—& I presume this state was named for him . . .

This is just to ask you a question. I've been asked here to recommend poets for this job, and I wondered if by any chance you would consider it sometime. I have already given your name to Robert Heilman, the head of the English Dept. (& very nice, too), so he may even have written you by now for all I know, because he seemed to take to the idea. I had heard a rumour (I think from May Swenson) that you were leaving The New Yorker—or perhaps if not you could have a leave of absence.—You may not like the idea at all, but when they asked me about "poets" I thought of you. The Poet can come for one, two (like me), or three "quarters" and the pay is $7,000 a quarter—Which seems very good by my humble standards! That is $7,000 each ten weeks, more or less. There are only 2 small classes—15 to 20—and they meet for 50 minutes, supposedly 4 times a week but I have cut the writing class to 3 times a week. This part of the world, and the breezy western manner, and teaching, rather staggered me at first— but now I am beginning to enjoy most of it except the classes —but then you did teach before, didn't you? [handwritten: "They are very nice to one, too—"]

Well—I am not urging this on you! I just thought I'd explain how it came about, in case you do hear from Mr. Heilman or a Mr. James Hall . . . Also—one is a full professor for the term, because Roethke was. One does feel a bit like his ghost, of course. This year Henry Reed is here—he had this job, too, two years ago—and he brightens things for me a great deal. I wish you would get him to send you something for The New Yorker—I am sure he has some poems somewhere, and I think he is a beautiful poet, don't you? c/o the Eng. Dept. here would reach him.

If you can think of anyone else who might like it—Anthony Hecht?—you might let me know—The biggest drawback is that one has no time for one's own work, or I don't—perhaps someone more experienced at "teaching" would. (I feel a complete fraud as far as teaching goes.) May has a job for next year or I might suggest her. Who else?

I hope you are well and cheerful—and I hope to see you in New York sometime before I retreat to the other side of the Equator again—

With love,

Elizabeth

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

From the Collection of Thomas Hardy Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto:

Max Gate, Dorchester, 6 May 1936

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed, poet, dramatist, and would-be Hardy biographer concerning Hardy's poem 'Looking Back' and Reed's prospective visit.1

Max Gate, Dorchester, 9 Aug. 1936

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed expressing her pleasure at seeing him and helping his research.

Max Gate, Dorchester, 25 Dec. [1936]

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed discouraging him with regards to any projected biography of Hardy and the possible performance of The Dynasts.

Max Gate, Dorchester, 21 Apr. 1937

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed concerning her illness and the desirability of his delaying the proposed biography of her husband.

1 "Looking Back" was first published in Richard L. Purdy's Thomas Hardy: A Bibliographic Study (London: Oxford University Press, 1954), p. 149.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

Some new finds in the British Library Archives & Manuscripts catalogue:

• Alvarez Papers. Vol. cxxiv. Add MS 88605: 1951-1989, "Henry Reed; n.d. Poems only (3)."

• Cockerell Papers. Vol. CXXIII. Add MS 52745: 1888-1961, "Henry Reed, broadcaster: Letter to S[ydney]. C. Cockerell: 1955" (this one we had in the bibliography already, thankfully!).

• Correspondence of Reinhardt and Potter. Add MS 88987/2/104: 1953-1954, "Henry Read [ sic] (to him)" (regarding Potter's 1964 Sense of Humour anthology).

• Dramatic Verse. Add MS 88984/6/34: 1963, "Contains correspondence and papers relating to a Festival session of specially commissioned dramatic verse. Includes correspondence with Ted Hughes, Christopher Logue, Henry Reed, Vernon Scannell, and Michael Baldwin."

• Lutyens Collection. Vol. cclxxxv. Add MS 64719: 1949-1963, "'Canterbury' (Henry Reed); n.d. (ff. 32-54). 320 x 250mm."

• Lutyens Collection. Vol. cccv. Add MS 64739: 1953-1964, "'Westminster Abbey' (Henry Reed); [1953]. (ff. 7-36). 370 x 255mm."

• Reed, Henry. Add MS 88908/8/6/5: 1948, "Reed to Tambimuttu (manuscript, Cyprus, 21 April, 1948), declining, without 'the books that might help me' and unable to 'squeeze an appropriate verse or two out of my head'" (Part of T.S. Eliot: A Symposium: Correspondence and Original Materials).

This last is another heartbreaking no-show; a result of Reed's seemingly endless writer's block.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

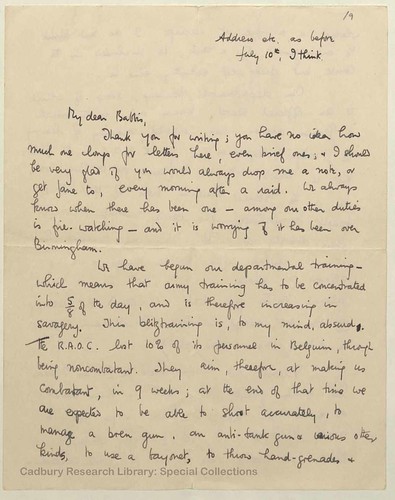

The Cadbury Research Library at the University of Birmingham, for Henry Reed's centenary, has very thoughtfully made available some selections from the Reed's papers on their Flickr page: Henry Reed: Behind the Scenes. There are scans of some of Reed's early writings from the University magazine, The Mermaid, photographs, and letters ( slideshow).

One of the more important items (or, at least, important to me), is a letter Reed wrote to his sister Gladys (affectionately called "Babbis," married to Joe; Henry, is of course, Prince "Hal" to his family). This letter was quoted by Professor Jon Stallworthy for his Introduction to Reed's Collected Poems (Oxford University Press, 1991; Carcanet, 2007), and was written at nearly the same time as another (similar) letter to John Lehmann: during the summer of 1941, during the Birmingham Blitz and close on the heels Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union, whilst Reed is in the midst of his basic training, expecting to be sent into combat and doubtful of his effectiveness:

Address etc. as before

July 10th, I think My dear Babbis,

Thank you for writing; you have no idea how much one longs for letter here, even brief ones; and I should be very glad if you would always drop me a note, or get Jane to, every morning after a raid. We always know when there has been one — among our other duties is fire-watching — and it is worrying of it has been over Birmingham.

We have begun departmental training — which means that army training has to be concentrated into 5/8 of the day, and is therefore increasing in savagery. This blitztraining is, to my mind, absurd. The R.A.O.C. lost 10% of its personnel in Belgium, through being noncombatant. They aim, therefore, at making us combatant, in 9 weeks; at the end of that time we are expected to be able to shoot accurately, to manage a bren gun, an anti-tank gun and various other kinds, to use a bayonet, to throw hand-grenades and

[Page 2]:

whatnot and to fire at aircraft. I do not think the management of a tank is included in the course, but pretty well everything else is.

Our departmental training, some of which is an official secret, known only to the British and German armies, has consisted mainly of learning the strategic disposition of the R.A.O.C. in the field: this is based, not, as I feared, on the Boer War, but on the Franco-Prussian War of 1871. It is taught by the lecturers who rarely manage to conceal their dubiety at what they are teaching. But it is restful after the other things, and we are allowed to attend in P.T. 'kit'. This is nicely balanced by the fact that we attend P.T. wearing all our 'kit', except blankets. (I will never call a child of mine Christopher.)

Please let mother have the £1, as I know how much greater her need is than mine; I do assure you that I have, so far, all the money I need. I get £1 every Friday, and should get more, were it not for some compulsory

[Page 3]:

voluntary deduction which they make; and I don't seem to spend even £1. I am still too tired to go out much at night, the beer here is undrinkable and I am having to give up smoking, as my lungs will not stand the strain of smoking and the other things they are called upon to do. So, I am comparatively well off; I should be glad of some more cheques: as this will be my last chance of paying much to my debtors I thought I'd better pay them all a little bit. This, I'm afraid involves a lot of cheques, and if you could let me have another half dozen, it would greatly help me.

I should be glad to have the New Statesman, if that is possible; it comes out on Friday, and if I got it by Saturday that would be marvelous.

I hope a good deal from Russia, of course, but rather joylessly: the scale of it all is beyond my grasp, and it is terrible to see a country

[Page 4]:

which, with all its faults, has been alone in working to give the fruits of labour to the people who have earned them, thus attacked; I think you should think about Russia very seriously, and try to learn something about her, and try to find why she can perhaps do things that we cannot — things that France, for example, could not. Stalin and Molotoff may be bureaucratic villains: I don't know. But if they are, they are only the passing evil which cannot wipe out what the period of Lenin gave. While we — we are only beginning to turn up a little doubtful virtue in our rulers, after decades of Chamberlain big business. And big business still can stifle the efforts at wise government here, as any workman you meet on a train will tell you. The British people are fighting a battle on two fronts, at home and against Germany: so far we have only been able to hurt Italy, who is fighting a battle on three: against us, against the banker-princes,

[Page 5]:

and against Germany also; Russia has fought, and largely won, her battle against capitalism. She is only fighting Germany now. That is why she may win; without that earlier victory, her enormous size would avail her nothing in these days. And when she is secure against fascism (which isn't confined to Germany and Italy) perhaps the horrible side of Russia will fade away more rapidly than now seems possible.

I don't know what to say about Joe. It is clear that an officers' mess is a decadent place, even if there are in it people as gallant and intelligent as Joe and a few of my own friends who have recently got commissions; I gather that an officers' mess is boring and dull, and therefore easy to set up expensive forms of distraction in; and I suppose most of Joe's companions were regular commissions officers, who are usually stupid and illiterate (our Lieut-Col. told us we were now fighting alone, last

[Page 6]:

week, since France failed us; I suppose he hadn't heard about Russia) and they may lead him astray, which could happen very easily, I think, knowing Joe. If you think telling him about the O.D. would shock him into remorse, do so; I think this would be the best way. It means great inconvenience to you, always to shoulder Joe's burdens like this, but eventually it ought to aruse his conscience. The time for a general settlement will be after the war is over; everybody will be so shatteringly poor then, that things will probably settle themselves, even overdrafts.

The enclosed is a present (not a repayment — not yet) from me; I am keen on its being divided thus, and thus only: 5/- for mother (for her birthday), 1/6 for Jane (because why should she have any more than that) and 13/6 for you (to be spent as "pocket-money"

[Page 7]:

on oddments, meals and so on, because by now you ought to be learning what it feels like to have 13/6). Please do this arrangement for me, as faithfully as if it were a will.

And write again soon.

All my fondest love to you all.

Hal.

I hope to find time to transcribe more of these letters from Henry. Click here to see the University of Birmingham Special Collections' catalog record for Henry Reed's letters to his family.

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

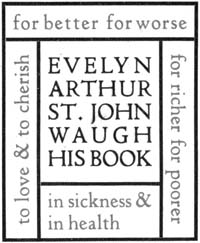

Maggs Bros., Ltd., is a London-based rare book and manuscript dealer, in business for over a century and a half. Here, in their inventory, is a listing for catalogue 1446, " Books from the Library of Douglas Cleverdon, 1903-1987." Cleverdon was a small press publisher and BBC radio producer. If you are a font-fanatic, you might be interested to know that Gill Sans, designed by Eric Gill, was originally created for the signboard over Cleverdon's bookshop in Bristol.

Among his credits as a radio producer, Cleverdon was responsible for the adaptation of David Jones's In Parenthesis (1948); Henry Reed's Italia prize-winning drama, Return to Naples (1950); Dylan Thomas's Under Milk Wood (1954); as well as all the plays in Reed's seven-part Hilda Tablet sequence (1953-1959). All in all, Cleverdon produced over two hundred programs for the BBC.

There's a fine article by Alex Hamilton on Cleverdon's achievements, "The Third Man," in The Guardian from November 20, 1971, which accompanied a profile on Henry Reed for the publication of the Hilda plays.

The Maggs Bros. catalogue, which is from 2010, includes this item:

54 REED (Henry). Returning of Issue. 54 REED (Henry). Returning of Issue.

Original heavily corrected manuscript and heavily corrected typescript of the fifth and final poem in Henry Reedís The Complete Lessons of the War series, inscribed by Reed: "To Douglas & Nest Cleverdon with love and gratitude Henry Reed, July 29, 1965". With a note from Henry Reed confirming Cleverdonís ownership of the manuscript and a note from the BBC allowing this gift from Reed to Cleverdon. £4000

Together with 23 TLS and ALS from Reed, predominantly to Douglas but with a couple to Nest and one to their elder son Lewis. Mostly in the mid 1960s and about radio drama and poetry by Henry Reed and the BBC but with 7 from 1950-51, also about Reedís radio work. One is in the character of the spinster "Emma Titt-Robbins", Tablet was the protagonist of Reedís satire The Private Life of Hilda Tablet, broadcast in 1954.

The catalogue also includes Cleverdon's personal, inscribed copy of Reed's poems, A Map of Verona.

I don't know if anyone snapped up the Reed manuscripts and letters back in 2010, but if I had £4000 pocket change, I would donate them to the University of Birmingham's Special Collections, to go with rest of Reed's papers and manuscripts.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

fonds (fôndz; Fr. fôn) n. the entire body of records of an organization, family, or individual that have been created and accumulated as the result of an organic process reflecting the functions of the creator. I work in a library, albeit in a low-level administrative capacity, and I pride myself on knowing the lingo. But I've never come across this term before. Probably because it's been adopted from the French, meaning "foundation" or "groundwork"; a lace-making term. In the archival sense, a fonds is a meta-collection made up of smaller collections of papers and works, all based upon—or originating from—a single source or author.

In the Robin Skelton Fonds, University of Victoria McPherson Library Special Collections, we find this entry for a letter from Henry Reed:

Reed, Henry. 1 in, 1963, als. Includes ts. of poem, "Movement of Bodies" by Reed. With the abbreviations unabbreviated, that translates into: "From Henry Reed: one incoming letter dated 1963, handwritten and signed, which includes a typewritten copy of his poem, ' Movement of Bodies'."

Robin Skelton (1925-1997) was a poet and critic, and a professor of English literature at the University of Victoria, British Columbia. We know him primarily for editing two anthologies which include Reed's poems: The Poetry of the Thirties (Penguin, 1964), and The Poetry of the Forties (1968).

It's easy to imagine that Reed's letter pertains to his inclusion in either anthology, but the typescript of "Movement of Bodies" is problematic: it doesn't appear in either book. The Poetry of the Thirties has an early poem of Reed's, "Hiding Beneath the Furze," and the Forties anthology contains "Naming of Parts," "Judging Distances," "Unarmed Combat," and a lesser-known poem, "The Wall." Perhaps there's something interesting here, or perhaps Skelton just declined to include a fourth Lessons of the War poem.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

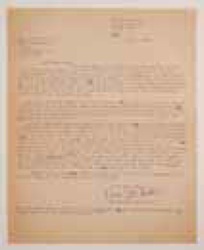

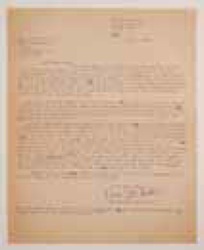

Deep in the Written Archives of the BBC is a collection of letters and memos relating to George Orwell's time as a Talks Producer with the Eastern Service, writing and broadcasting wartime news and propaganda to India from 1941 to 1943. The archive continues to follow Orwell's activities even after his resignation, in the correspondence of Rayner Heppenstall: poet, writer, and producer of features and drama at the BBC from 1945 until 1967. A selection of these documents have been dutifully reproduced for the digital collection, George Orwell at the BBC.

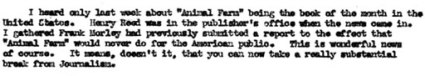

In a letter dated July 8, 1946, Heppenstall belatedly congratulates Orwell on Animal Farm being selected for a future "Book of the Month Club" edition in the United States. Heppenstall received the announcement, apparently, via Henry Reed, who "was in the publisher's office when the news came in":

Click the image to see Heppenstall's original letter at the BBC Archive, or here for the plain text version.

Reed's friendship with Rayner Heppenstall is well documented. In his 1969 memoir, Portrait of the Artist as a Professional Man, Heppenstall brags about introducing Reed (and a host of other BBC writers and staff) to the Stag's Head Pub, across the street from the Features and Drama offices on London's New Cavendish Street. Heppenstall produced Reed's second radio play for the Third Programme, Pytheas: A Dramatic Speculation, in 1947.

What I am having difficulty figuring out is: which publisher's office was Reed visiting in 1946, when he heard the book club news? Animal Farm was originally published in 1945 by Martin Secker & Warburg, London, but the American edition of Orwell's "fairy tale" was released the following year by Harcourt Brace, New York. Much of Heppenstall's output of the 1940s, however, was also published by Secker & Warburg. Frank V. Morley, whom Heppenstall mentions, was a director at Faber and Faber. Henry Reed did publish a book with Secker, an English translation of Buzatti's Larger than Life, but not until 1962. Confusing. And I've only had coffee for dinner; too much coffee.

It seems most likely, given the time frame, that Reed was simply visiting the publisher of his own first book of poetry, Jonathan Cape, who had only recently released A Map of Verona: Poems in May, 1946. Is that how you read it?

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

Published last October, Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell (edited by Thomas Travisano and Saskia Hamilton, Farrar, 2008), finally reveals both sides of a conversation I discovered last spring, in The Letters of Robert Lowell (Hamilton, ed., 2005).

Bishop and Lowell first began exchanging letters in 1947, after meeting at a party given by Randall Jarrell. In the mid-60s, Bishop met Henry Reed when they were both teaching at the University of Washington, Seattle. Here are the relevant excerpts from the Bishop-Lowell correspondence, which include several classic Reed witticisms, expressions of Bishop's admiration and concern for her new friend, and even a mention of Reed's desire to expatriate to the United States (!): June 15, 1965 Dearest Elizabeth,

I rather hope you'll take in the Washington job. You'll like the landscape and the relative quiet for America, and I think [Robert] Heilman, the head of the department, will shape the conditions [to] suit you. He did marvels with Ted Roethke and has since had such unacademic shy people as Henry Reed and Vernon Watkins. Everyone seems terribly excited for your arrival...[.]

All my love,

Cal

(p. 576)

Apt. 212, 4135 Brooklyn Ave., N.E.

Seattle, Washington, 98105

Washington's Birthday

[Feb. 23, 1966] Dearest Cal:

I don't know where to begin. You are much admired here and several of my "students" ) I have to keep putting everything in quotes because none of it seems quite real to me, even now) are using you for their term-papers . . . you are being compared (to his discredit) frequently with Eliot, I think—Henry Reed is here—a bright spot in my life, I must say. I had dinner with him last night and he told me how he had heard a beautiful reading of SKUNK HOUR in England—and was reported in the papers as having said in a loud aside, "That's the only poem worth a damn this whole evening." He was sorry not to have met you here and would very much like to when he goes to New York.—I'm not sure when. He is extremely funny—referred to Olivier in OTHELLO as "The Nigger of the Narcissus," to give you an idea of his wit. I shall make so bold as to give him your address. He has done a few beautiful poems since "Naming of Parts" ("to which I owe my livelihood," he says) he has shown me—but I think writes really very little...[.]

Well, I was never meant to be a teacher and would never like it—but I do like the "students" (children, I call them to myself)—even if they seem awfully lacking in joie de vivre and keep telling me about their experience with LSD and "pot" etc., and (2 girls) how they are "on the PILL"—I think this was to convince me they are serious about writing! The boys are all over six feet—some girls are, too—and the girls have huge legs—& have blue eyes; one left-handed—what is this high percentage of left-handedness, I wonder? Henry said he'd been warned about the bosom in the front row—but not about the large bare knee that starts creeping up over the edge of the table . . . [.]

Love,

Elizabeth

(pp. 598, 599)

Samambaia, September 25th, 1966 Dearest Cal:

I might see Henry Reed in London. He was a wonderful comfort to me in Seattle—and I think I was to him, too. He is a sad man, though, perhaps because he hasn't been able to work for so long—I don't really know—but funny as can be at the same time. We cheered each other up through exams by midnight telephone calls telling each other the best things we'd found. He was teaching "Romeo & Juliet" to about 60 freshman, poor dear. My favorite of his was a girl's paper that began "Lady Capulet is definitely older than her daughter but she remains a woman." One boy: "Romeo was determined to sleep in the tomb of the Catapults" . . . etc.—Henry is going back for the winter term of the job I had, again. He wants to settle in the USA, being very romantically fond of it, I think, although he's seen nothing at all except some of the west coast. I think he is a wonderful teacher—too good, really for Un. of W.—if you have any ideas of a course he could give somewhere else I wish you'd let me know . . . I think I'll write Dick Wilbur. I know nothing of the Wesleyan things, but perhaps when my grant is over and that book is done, I might apply for one. I think it would do both Lota and me a lot of good to stay in Connecticut for a few months!—seeing New York, but not IN it. I don't think I'll ever feel tough enough for New York again, somehow...[.]

—Much much love,

Elizabeth

(p. 608)

October 2, 1966 Dearest Elizabeth:

How lovely to hear from you again in all your old leisurely fullness. Sorry that Seattle was a grind and that Lota has had so much too much work. I have to fly up to Harvard soon for my weekly classes there, so will just dash off this letter, trying to answer and comment on your letter. The man in charge of Wesleyan is Paul Horgan, a Colorado or Arizona novelist. We know him quite well, and will get in touch with him, if you and Lota & Henry Reed are really interested. It's a queer place, about a dozen people in residence, some with wives, some without, an office, rooms or a house. Lizzie and I were offered about $20,000 to stay there a year, but so far have held off, not wanting to change Harriet's school, preferring to be in New York. It can be rather melancholy, but all depends on who is there—usually several people from Europe, ages older and more uniformly distinguished than Yaddo. The I.A. Richards are there now, later the Spenders are coming. Always someone. No duties, though it's suggested that you informally meet students. It might be perfect for you both. Let me know, and I'll start writing and calling people...[.]

I'd think a lot of places would like to have Henry Reed. Everyone speaks well of him, and he is quote famous and admired for his one book. He's a great friend of our friend the actress Irene Worth...[.]

All my love,

Cal

(pp. 609, 610)

August 28th, 196[8] Dearest Cal:

Since I am being so gossipy—I loved your account of yr. visit to Mr. Rubberheart (as Henry R calls him). Much worse than my simple evening sallies here . . . It was particularly funny since I had just had a letter from him—Mr. R [poet Richard Eberhart]—I received two copies of his last book and felt I had to say something honest, I thought. In return I got a long letter all about people I never heard of with names like Tricksy and Adam . . . Grandma and Mrs. Crosby "both 79," etc, etc...[.]

With much love always—

Elizabeth

(p. 648)

While I'm certain Reed's anecdote about his overly-loud commentary on Lowell's poem is true, I think the fact that he was quoted in the London newspapers is probably an exaggeration. Bishop's letter of September 25, 1966 is likely the source of Brett Millier's mention of Reed and Bishop's late-night Seattle telephone conversations, in Elizabeth Bishop: Life and the Memory of It (University of California, 1995). The American actress, Irene Worth (pronounced i-REE-nee), starred in Reed's adaptation of Ugo Betti's The Queen and the Rebels, staged in London's Haymarket Theatre in 1955.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

Continuing to peck through library archives and special collections, I've found a letter (or letters) from Henry Reed, written to Denys Kilham Roberts, in the Historical and Literary Manuscript Collections at the University of Iowa. From the index to their finding aids:

ROBERTS, DENYS KILHAM. Papers of Denys Kilham Roberts. 1.5 ft. Correspondence to and from a British writer of the 1920s and 1930s. MsC828. Iowa's index doesn't go into greater detail, but the library catalog does: "Roberts, Denys Kilham, 1903-1976. Correspondence, 1930-1964," with letters from (and/or to?): E.M. Forster, David Gascoyne, Wilfrid Gibson, Robert Graves, Herbert Read, Edward Sackville-West, Siegfried Sassoon, George Bernard Shaw, Julian Symons, and Evelyn Waugh, among many others (Reed included). A summary describes the collection:

Discussing his publications and those of his correspondents; concerning a BBC program titled "Catchword Songs"; soliciting literary contributions to various publications; encouraging other writers.

Roberts compiled and edited numerous poetry anthologies during the 1930s, '40s, and '50s, including the five-volume The Centuries' Poetry (1938-1942). He also served as Secretary of the Society of Authors during the 1940s, and edited Penguin Parade, a showcase of "New stories, poems, etc. by contemporary writers," between 1937 and 1945.

At first I was hopeful that Roberts may have solicited a poem from Reed for Penguin Parade, but looking at all the available covers in AbeBooks turns up nothing. A quick look at the bibliography, however, reveals Roberts listed as one of the editors of the journal Orion: A Miscellany, to which Reed contributed twice: his poem "King Mark" ( 1945), and the essay "Joyce's Progress" ( Autumn, 1947). It would seem logical that Reed's correspondence would be in regards to one of, or both of, his Orion appearances. Alas, Iowa provides no dates.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

I came across a curious reference this evening, to a " Collection, 1924-1983," with a laundry list of associated names: J.R. Ackerley, Brigid Brophy, Edward Carpenter, Rena Clayphan, G. Lowes Dickinson, George Duthuit, Roy Broadbent Fuller, Sir John Gielgud, Henry Festing Jones, James Kirkup, Francis Henry King, Rosamond Lehmann, Desmond MacCarthy, James MacGibbon, Sean O'Faolain, Sir Herbert Edward Read, Henry Reed, and Vita Sackville-West. But no location, no source, and only a partial title. Obviously the record was uploaded from a library catalog, somewhere. But where?

I had a feeling the people on the list had something (or someone) in common, but I couldn't puzzle it out. I searched the Location Register. I searched for library and .edu holdings. And then I suddenly remembered my WarGames, where Lightman (Matthew Broderick) is counseled to "go straight through Falken's Maze," the first game on his list. Ackerley. Joe Ackerley is the first name in the list. Protovision, I have you now.

I don't know why I didn't think of it straight off: an easy search of WorldCat turns the collection up, at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin:

Following the holdings library on WorldCat whisks you into the University of Texas Libraries' catalog record for " Ackerley, J.R., Collection 1924-1983". And there, among the cardboard boxes filled with manila folders and acid-free envelopes, are four letters from Henry Reed to Ackerley, dated from 1937 to 1942. During those years, Ackerley was editing the BBC's magazine, The Listener, where Reed published his first poems. But wait, there's more!

Led by the tantalizingly linked author field " Reed, Henry, 1914-1986" in the collection's catalog record, we discover that the Ransom Center's book collection has quite a few editions of Reed's, including signed copies of A Map of Verona originally presented to Ackerley and Edith Sitwell, as well as Evelyn Waugh's personal copy (with bookplate). I can't begin to tell you how marvelous it is that the Texas Libraries thoughtfully provides a "Bookmark Link" feature: static URLs for all their records.

The Ransom Center's Ackerley collection isn't detailed in their online finding aids, but at the end of the maze I also turned up a copy of a letter to Reed in the correspondence files for Alfred A. Knopf.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

In November of 1947, Henry Reed wrote a letter to George Barnes, Controller for the BBC's Third Programme ( picture of Barnes, later the Director of BBC Television). The letter was ostensibly about a radio adaptation of The Dynasts, Thomas Hardy's epic verse drama of the Napoleonic Wars. Reed, however, took the time to expound on the art of broadcasting, specifically rejecting the idea that the dramatist's main role is to maintain the illusion for the listener. An excerpt from this letter appears in John Drakakis' Introduction to British Radio Drama:

It is a myth that Radio has any capacity for inducing in the mind of the listener anything in the nature of particularized visualization. You might, once in an evening persuade him to see one of those great stage directions; but not, I think, more than one. For when radio had to suggest a scene to the listener, it does best to give only a brief powerful hint from which, with the help of specially written dialogue designed to an end, the listener can without effort and perhaps only half-consciously, construct a scene from the innumerable landscapes or roomscapes (!) bundled away in his own memory. (p. 22-23)

Apparently, having had a total of two full-length plays broadcast in 1947 ( Moby Dick, and Pytheas), Reed felt confident enough to tell the Controller how radio works, and how their listeners listen. Reed's six-part adaptation of Hardy's Dynasts was broadcast on consecutive evenings in June of 1951. The original letter resides in the BBC Written Archives.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

Two fortuitous happenings this weekend. Firstly: more than a week ago—before I traipsed down to Duke University and back, even—I photocopied two articles from 1961 at the university library. One was Reed's book review of Emma Hardy's Some Recollections from The Listener, and the other was a review of Three Plays, by Ugo Betti, from Prairie Schooner. In my haste to read the Listener article, I managed to leave the Schooner review on the copier output tray.

Going back to the library this evening, I re-pulled the 1961 Prairie Schooner volume from the shelf, and when I arrived at the photocopier what should I find? My copies from the previous week, neatly arranged on the adjacent work table. Buddha bless Duplication Services!

The second happening took place at the local Barnes & Noble, where I was attempting to take account of all the articles, reviews, and letters I had dug up down at Duke. B&N's wireless service conked out after an hour or so, however, so after I had finished licking the inside of my coffee cup, I went down to peruse the Poetry section on my way out. A paperback copy of The Letters of Robert Lowell (bn.com) caught my eye, and I immediately turned to the index, under "R". There was one entry for Reed, in a letter to Elizabeth Bishop, who had left Brazil to take a job teaching at the University of Washington, Seattle:

February 25, 1966

Dearest Elizabeth:

Wonderful your letters are pouring out again. I had terrible pictures of you despondent and lost in the new toil of teaching—lonely, cold at sea. Lizzie taught last term at Barnard for the first time in her life. Her first comment was 'the students aren't very good, but I am...[.]'

Your book is another species from almost everything else. I think even the reviewers now see that there's no one, except Marianne Moore at all comparable to you. I guess I struck Roethke under a bit more favorable circumstance. I mean last year when I came to Seattle, I was to give the Roethke Memorial reading and had worked myself into the proper state of awe...[.]

Do tell Reed to come and see us. He must have saved your heart in exile. What a difference an intelligent voice makes. Our Guadeloupe beach was restoring, but one felt stupider than the stupidest tourist—and was!

All my love,

Cal

Lowell signed all his letters to friends as "Cal". Bishop must have mentioned that Reed was also teaching at the university in a preceding letter.

I was pleased to discover that Lowell's Letters are arranged the way a collection of correspondence should be; the credit going to the editor, Saskia Hamilton. There is a substantial appendix of notes at the end of the volume, detailing all the obscure and personal references in the letters; a list of all the manuscript collections where the letters were collected from; and a list of all the addresses Lowell lived at and wrote from. At the time, in 1966, Lowell was living at West 67th Street, New York.

I have no idea if Bishop ever passed along Lowell's invitation for a visit.

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

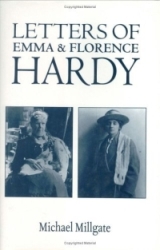

A heartbreaking turn of events appeared this evening, in Michael Millgate's Letters of Emma and Florence Hardy (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996). In a letter dated December 7, 1936, Florence Hardy (then aged 57) mentions 'A young man from one of the universities visiting me a few weeks ago said that all the stories one heard were amusing yet the time might come when the nation would be tired of a comic Royal Family.' Millgate notes this "young man" was none other than Henry Reed. In 1936, Reed had graduated with an MA from the University of Birmingham, and he was compiling material and interviewing contemporaries for his planned biography of Thomas Hardy.

Later, Millgate produces a letter to Reed from Florence Hardy: To Henry Reed

max gate, | dorchester, | dorset.

25th Dec. (1936)

Dear Mr. Reed,

I have been thinking very long & seriously about the book we discussed when you were here, and the more I think about it the more impossible it seems. My own memory is not good & becomes worse & worse, & probably I have exaggerated in my own mind much that was told me, &, as for Miss [Katherine "Kate"] Hardy, she is an old lady in bad health, who has, during the last days lost her nearest surviving relative [cousin Polly Antell] & she will not see any stranger, nor will the doctor allow her her to do so. Moreover she would refuse to discuss any member of her family with anyone. It is possible that I built up a great deal on a few careless remarks from prejudiced persons. I should be very sorry to put into print more than is in my biography as there is not a scrap of documentary evidence to go upon.

Also, with regard to a stage version of 'The Dynasts'—I find that my husband left very special instructions about that, & any performance by amateurs, except the O.U.D.S [Oxford University Dramatic Society], is prohibited. I am sorry to be so negative on both these points, but I hope you will understand.

With seasonable wishes,

Yours sincerely,

Florence Hardy.

Reed's literary hopes and dreams were swept away in the span of two small paragraphs. According to Millgate's notes, the project Florence deems "impossible" was a biography of Thomas Hardy which Reed had suggested, to be based on his conversations with Florence and Hardy's cousin Kate. And apparently Reed was also hoping to adapt Hardy's epic verse-drama on the Napoleonic Wars, "The Dynasts," into a stage play, perhaps for the Highbury Little Theatre group, in Birmingham.

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

An unconfirmed sighting appears in the archives of a Midwestern university: a letter from a 'Henry Reed' to Father Peter Milward, S.J., in the Small Manuscript Collection of the University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, Minnesota: 'Reed, Henry, one ALS to Fr. Peter Milward, 1975.'

I was quick to dismiss this as coincidence, until discovering that Father Milward is a renowned Shakespeare scholar. From "Fifty Years of Milward," in the Spring, 2002 Shakespeare Newsletter:

Milward, originally from England, has spent a half century teaching at Sophia University in Tokyo, Japan. He is the founder or co-founder of numerous societies and organizations in Japan, most notably the Renaissance Institute, founded in 1971 to promote the scholarly vision of continuity between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, in the spirit of C. S. Lewis. He is the author of over 300 books, which range from scholarship to poetry to educational guides for Japanese students.

Milward's ["Fifty Years of Shakespeare, 1952-2002"] lecture at Boston College marked the establishment of the Peter Milward Special Collection (links mine) at Burns Library, which now has a more or less complete collection of Milward's Shakespeareana, and a generous selection of his other works. Boston College's scholarly journal, Religion and the Arts, is planning a sizable volume of essays on Shakespeare and the Reformation. Milward was therefore invited as a major figure in establishing Shakespeare's Reformation contexts, especially through his landmark book, Shakespeare's Religious Background, which argued for both Catholic and Anglican contexts.

Milward, it turns out, was one of the first to argue that Shakespeare was a practicing Catholic. He has also written extensively on Gerard Manly Hopkins (he is the honorary president of the Tokyo branch of the Hopkins Society of Japan), and T.S. Eliot.

While still unlikely, it seems entirely plausible that Reed may have written Father Milward to congratulate him on some publication on Shakespeare, or to argue some minuscule point of Eliot scholarship.

|

1528. Manning, Hugo. "Recent Verse." Books of the Day, Guardian (Manchester), 31 July 1946, 3.

Manning feels that 'Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship.'

|

Oscar Williams is a familiar name. His Little Treasury poetry series and other anthologies are known the world over. At least four collect poems by Henry Reed: The War Poets: An Anthology of War Poetry of the 20th Century (1945), A Little Treasury of Modern Poetry, English and American (1950), A Little Treasury of British Poetry: The Chief Poets from 1500 to 1950 (1951), and An Album of Modern Poetry: An Anthology Read by the Poets (1959). There are certainly (probably) more.

Though Williams is familiar as an editor and anthologist, he was a poet in his own right, and while my Granger's lists 26 poems in various anthologies, I am pressed to find a single verse of his online.

Not surprisingly, Williams' correspondence with authors and poets is voluminous and manifold: his collected papers at Indiana University's Lilly Library contains over 11,000 items, including 6,300 photographs of the likes of Conrad Aiken, Anatole Broyard, Richard Eberhart, Robert Frost, Anne Sexton, and Dylan Thomas.

Hidden amidst this trove of treasures is a (carbon copy of a) letter from Williams to Reed, dated July 9th, 1959, and a 1963 letter to Reed, along with Reed's response (carbons, also)! See the " Index to Correspondents."

The index also contains a minor literary mystery: a letter from one Henry J. Dubester, addressed to Henry Reed and dated October 2nd, 1959.

Dubester, as near as I can figure, was Chief of the Census Library Project, at the Library of Congress, sometime in the late 1940s and early 1950s, in charge of cataloging and indexing censuses and vital statistics. The Williams collection contains letters from Dubester to an absolute litany of poets, including W.H. Auden, William Empson, Roy Fuller, Robert Graves, W.S. Merwin, Theodore Roethke, Delmore Schwartz, Stephen Spender, and Richard Wilbur, among many others.

So, my question is (or my questions are): What was a bibliographer doing, writing to all these authors and poets? And how did copies end up collected among Williams' papers?

|

1527. Rosenthal, M.L. "Experience and Poetry." Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review (New York), 17 October 1948, 28.

Rosenthal says Reed shares with Laurie Lee 'that unhappy vice of young intellectuals—a certain blandness of which the ever-simple irony is a symptom.'

|

Up this morning, showered, and strolled down my dead-end end street to the 7-11 for coffee and a Sunday New York Times. It's warmer this morning than it has been so far this spring, 70į already at 7:30 a.m. and I'm tempted to finally reverse the vents in the apartment ó open them on the second floor and close them up downstairs ó and turn on the air conditioning.

I'm listening to an encore webcast of last night's A Prairie Home Companion, an encore of a rerun. I just want to hear the Guy Noir sketch. Plus, I don't why I buy the NYT on Sundays. I only read the Styles section, Arts and Leisure, the Book Review and Magazine. Three dollars' worth of a seven dollar paper. The rest is just news-news, and I either pitch it, or use it to wash the windows.

Yesterday, I followed up on cataloguing some records from the Location Register of 20th-Century English Literary Manuscripts and Letters. Published in print as two (large) volumes in 1988, the Register is now available online as a searchable database (using Sirsi's iBistro interface, no less), including updated records and new accessions from 1988 to 2003.

A quick search for "henry reed" pulls up 23 records, which includes autograph drafts of poems, notes for plays, and personal letters from Reed to such notable figures as Sydney Carlyle Cockerell, T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, L.P. Hartley, Emyr Humphreys, Rona Laurie, Kingsley Martin, and the actor John Phillips (who was also born in Birmingham the same year as Reed).

The Location Register is a powerful tool because it includes descriptions for individual items, not just entire collections. This is handy-dandy for locating material for a minor-Canon figure like Reed. For instance, nowhere does the University of Birmingham's description for the Papers of Henry Reed include this detail from the LocReg: Author: Reed, Henry, 1914-1986.

Title: Letters and postcards from Henry Reed to Michael Ramsbotham.

Date: 1944-1985.

Physical extent: 77 items.

General note: With 2 postcards from Reed, 1 to Col. & Mrs H.W. Ramsbotham and 1 to Mr. S. Marangos.

Call number: In Henry Reed papers, 9/1&3 Who, or what, is "Mr. S. Marangos"?

|

1526. Blunden, Edmund. "Poets and Poetry." Bookman, n.s., 1, no. 4 (July 1946): 14-15.

Edmund Blunden says Reed's Lessons of the War poems 'have captured something of the time-spirit and ambiguity of the recent war in a style of wit and deep feeling united.'

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|