|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Hardy"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

From the Collection of Thomas Hardy Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto:

Max Gate, Dorchester, 6 May 1936

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed, poet, dramatist, and would-be Hardy biographer concerning Hardy's poem 'Looking Back' and Reed's prospective visit.1

Max Gate, Dorchester, 9 Aug. 1936

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed expressing her pleasure at seeing him and helping his research.

Max Gate, Dorchester, 25 Dec. [1936]

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed discouraging him with regards to any projected biography of Hardy and the possible performance of The Dynasts.

Max Gate, Dorchester, 21 Apr. 1937

Hardy, Florence Emily (2nd wife) A.L.S. (with envelope) to Henry Reed concerning her illness and the desirability of his delaying the proposed biography of her husband.

1 "Looking Back" was first published in Richard L. Purdy's Thomas Hardy: A Bibliographic Study (London: Oxford University Press, 1954), p. 149.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

Henry Reed was, for a short time in the 1930s and 40s, the consummate Hardy scholar. Reed wrote his master's thesis at the University of Birmingham on " The Early Life and Works of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1878." He visited Florence Emily Hardy in 1936 as part of his research, and sat in Hardy's study at Max Gate transcribing letters.

Reed's ambition was to write the life of Thomas Hardy. He was thwarted by his own perfectionism, and — according to this 1962 review from the Sunday Telegraph of the republication in one volume of Florence Hardy's Life of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1928 — by Thomas Hardy, himself. The official biography which was published in 1928 and 1930 was nothing less than Hardy's own autobiography.

Reed's scholarly adventures eventually provided the fodder for his sequence of Hilda Tablet radio plays featuring the late "poet's novelist," Richard Shewin, as a stand-in for Hardy.

Reed's frustration with trying to write his own life of Hardy is scarcely disguised in his book review, but it can also be heard the most perfect parody of Hardy's poetry, " Stoutheart on the Southern Railway," written by Reed sometime in the 1950s:

What are you doing, oh high-souled lad,

Writing a book about me?

And peering so closely at good and bad,

That one thing you do not see:

A shadow which falls on your writing-pad;

It is not of a sort to make men glad.

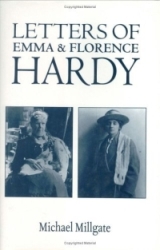

It were better should such unbe. When Reed finally abandoned his Hardy project he donated his notes to professor Michael Millgate, whose first book on Hardy, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, was published in 1972, with a full-blown Thomas Hardy: A Biography following in 1982.

Hardy's Secret

Self-Portrait

By HENRY REED

The Life of Thomas Hardy BY FLORENCE EMILY HARDY. Macmillan, 30s.

Many artists have led two lives, and out of consideration for their biographers they have usually contrived to lead them both at the same time. Thomas Hardy also had two lives, but they were inconveniently placed end to end.

There is a great division in his life round about 1897 when he ceased to be a novelist and returned to poetry. Biography of him will always be, from the point of view of shape, bedevilled by this fact.

There is plenty of incident, movement and emotional adventure in the first 57 years of his life. In the last 30 years that remained to him—from his own point of view his most valuable creative years—biographically dramatic landmarks are few indeed.

Official Life

The present volume suffers unavoidably from this tailing away of interest. It is the "official" life, originally published in two parts, the first in 1928 within a few months of Hardy's death, the second in 1930.

The work is still attributed on its title page to the second Mrs. Hardy, and we are left to wonder how its publishers have never got wind of the real facts of its composition, which were divulged as long ago as 1954 in Richard L. Purdy's monumental bibliographical study. The Life of Thomas Hardy is, in fact, save for its last four chapters, Hardy's own autobiography, and should be announced as such.

It is, by any standards, a ramshackle work, and its information is in may places demonstrably inaccurate even where there seems no point in disguise. But the book is packed with a miscellany of information not available elsewhere, and readers who care for Hardy will find it everywhere endearing, engaging, and full of his characteristic humour:

"There are two sorts of church people; those who go and those who don't go: there is only one sort of chapel-people; those who go."

There is, above all, the sense of being "with" Hardy himself: every page is invested with his own idiosyncrasies of vision and style.

Dorset Childhood

The early chapters are particularly impressive. He recreates his childhood and youth in Dorset and his days in London with fair objectivity. There is much room for correction of fact, but in mood and atmosphere his own account will scarcely be bettered.

Part of its charm comes, I think, from Hardy's genuine and characteristic modesty of manner. He was well on into his seventies when he embarked on the work, yet he never indulges in the reminiscent pride we so often have to wince at in writers' memoirs.

And there is no trace of that excessive self-esteem which sometimes indicates an unconscious sense of failure and is so painful in (to come no nearer to home) a writer like Bernard Shaw.

All the same, there is much that is defensive in these pages, and this provides strange matter for study. A good deal of care seems to have been taken to make things opaque when Hardy wished them to be.

Blank mendacity he rarely has recourse to: on the whole he probably tells fewer lies than most people. But he is at pains to mislead us about things that had affronted him in the circumstances of his own life or worried him in his relations with the highly class-conscious society of his time.

It is in his art that find the rectification of these evasions and deceptions. His art might often be bad art, its badness the more conspicuous for lying cheek by jowl with his incomparable best. But it was faithful to his own experience, and the recurrent themes of his fiction were the basic themes of his own life.

The contrast of humble birth and lofty aspiration, the struggle for education and learning, the uncertainty of passion, the dissatisfaction with marriage as solution to the problem of sex, the commonness of external adversity and of simple bad luck—all these went into his novels and his poems.

There is little or nothing of them, however, in the official life; and we are at times as conscious of this little-or-nothing as we would be if there were whole blank pages in the book.

Meant as Protest

However, the thing was not meant as confession: nor was it undertaken with any marked relish; quite the contrary. It came into being largely as a protest against recurrent public mis-statements about Hardy's own experiences. It was not meant to be a source for future biographies: it was meant to be an obstacle in their way.

So far it has proved highly successful in this aim. The biographical studies of Hardy published since his death compete lamentably with each other in the inaccuracy of their employment both of the "official" material given here and of the other pieces of significant information that seeped out in more recent years.

In the circumstances this republication—in a very convenient form—of Hardy's own account of himself is, for all its defects, a timely and refreshing recall to order.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

Robert Gittings was an author and poet, and from 1940 to 1963, a script writer and producer at the BBC. His award-winning book, John Keats (1968), is considered the definitive biography. Following this, he then set his sights on Thomas Hardy. From Gitting's obituary in the Times (London), of February 21, 1992:

Gittings's next project was a life of Thomas Hardy, of whom no biography had by then appeared that could be described as even adequate. His edition of Emma Hardy's Some Recollections (1961), done in collaboration with another writer, had received very rough handling from the late Henry Reed and was subsequently revised. Reed, who had known the second Mrs Hardy well, had for long been expected to write the definitive biography. But illness prevented that happening. Gittings failed to obtain Reed's co-operation in his work. This was a loss, as Michael Millgate's later biography, written with the benefit of Reed's expertise, showed.

Gittings accomplished his task in two volumes: Young Thomas Hardy (1975) and The Older Hardy (1978). These were received with respect and (especially the first volume) with gratitude for bringing hitherto unknown facts to light.

The "rough handling" of Gitting's 1961 book, Some Recollections By Emma Hardy and Some Relevant Poems By Thomas Hardy, comes from "Veteris Vestigia Flammae" ("scars of an old flame"), Reed's review in the Listener on October 26, 1961. Reed, of course, had spent decades on his own biography of Hardy, and may have taken offense that he was not consulted. He makes insinuations as to an over-reliance on what he calls "gossip," and then proceeds to call into question the editors' reliability:

It is a little surprising to see the name of Miss Evelyn Hardy [no relation] associated with the presentation of these difficult pages; her past achievements in the way of transcription have not been of a kind to beget confidence. It is to be hoped that the presence of Mr. Robert Gittings has guaranteed the general accuracy of the text; he has not, of course, been able to hold completely in check Miss Hardy's passion for irrelevant annotation: perhaps he feels that this has sometimes a wild charm of its own. Mr. Gittings has himself edited a small anthology of poems, appended to the main text, which may be considered to have a definite or possible derivation from the Recollections themselves. There is naturally room for minor disagreement about some of his choices, but most of what he has to say is very illuminating; and all of it is worth the closest attention. (p. 678)

Returning to Gitting's obituary, we note that Michael Millgate's 1982 life of Hardy, "written with the benefit of Reed's expertise" (as well as that of consummate bibliographer, Richard L. Purdy), would become the definitive Hardy biography. So how much, exactly, did Millgate benefit? Quite a bit, it turns out! Millgate inherited all of Reed's Hardy research and drafts. We can see, in the finding aids for the University of Toronto's Fisher Rare Book Library, a list of six boxes of notes, correspondence, and documents relating to Millgate's Hardy books. Among the items listed are:

Box 5, 17 folders (Howard Bliss/Henry Reed): (Folder 1) Howard Bliss/Lew Feldman correspondence

(Folder 2) Howard Bliss: inscribed, presentation or signed

(Folder 3) Henry Reed: drafted sections of projected Hardy biography

(Folder 4) Reed: misc. biographical passages re: Hardy

(Folder 5) Reed: notes and drafts re: Hardy novels

(Folder 6) Reed: Notes on conversations with Hardyís widow, 'Important'

(Folder 7) Reed: reviews of Hardy items, article on Hardy

(Folder 8) Reed: scripts for Hardy programs

(Folders 9-10) Reed: unpublished thesis on T.H. biography

(Folder 11) Reed: misc. reviews and lectures Ms. Michael Millgate

(Folder 12) Reed: misc. biographical items (clippings)

(Folder 13) Reed: MM correspondence, re: his papers

(Folder 14) Correspondence: Reed/Purdy, 1949-1977

(Folder 15) MM/Reed, carbons, 1969-1981

(Folders 16-17) Reedís comments on MMís Hardy biography Box 6, Henry Reed notebooks (5 holograph notebooks in box): (1) 1912-1913, brief intro. by Henry Reed on THís poems, Poems of 1912-1913

(2) HR notes on Dorchester 1851 census...

(3) HRís outlines of a few chapters of projected biography...

(4) HRís extensive notes (some on loose sheets) on Hardy family history

(5) HR notes on the early novels...

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

I thoroughly enjoyed the first half of the new BBC production of Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles, which aired last night on PBS Masterpiece. This adaptation stars the enchanting Gemma Arterton as Tess, and Hans Matheson as Alec D'Urberville.

I was seriously distracted, however, at the opening of Chapter 12, when the camera pans up from a bunch of Japonica in bloom, trained along a garden wall:

The shrub appears again, at the side of Mr. Clare (played by Kenneth Cranham) and son Angel (Eddie Redmayne), as they leave Emminster parsonage (I must be the only dude on the Internet taking screencaps which do not feature Gemma Arterton):

Fancy that, I thought. Henry Reed has taught me horticulture! The flower is definitely Chaenomeles, the Japanese Quince—probably Speciosa, or another ornamental variety—referred to commonly as Japonica. Filmed in early spring, March or April, at Hamswell House, South Gloucestershire.

You can catch up on the first half of Tess at PBS.org. The program concludes this Sunday evening, January 11th.

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

Henry Reed graduated from the University of Birmingham in 1936 at the age of 22, with a Master of Arts degree. At the time, he was the university's youngest MA.

Reed's (147-page) thesis was on " The Early Life and Works of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1878" (library catalog), a copy of which now resides in the Thomas Hardy Collection of the Dorchester Reference Library, Dorset:

Dorchester's Hardy Collection contains 'nearly 1,000 theses for higher degrees in typescript or microform,' as well as critical articles from various literary journals.

It would seem likely that the University of Birmingham still has a copy of Reed's thesis, but if they do, they don't seem to have cataloged it.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

Well, Hardy boys and girls, as with most things in life, the solution to yesterday's mystery would have been easily reached, had I simply paid better attention in math class. Or trusted in the radio times tables published in The Times.

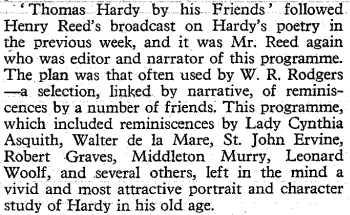

There is no great mystery: Henry Reed's radio tribute to Thomas Hardy was broadcast as advertised, on Sunday, February 20th, 1955, on the BBC Home Service, at 10:05 pm. Gibson's book had the date wrong, and I had mistakenly read "10.5" as 10:50, not 10:05. The Times, in their grand crusade for brevity and clarity, simply outsmarted me (not difficult to do, apparently). The program ran 47 minutes, until 10:52 pm. Here is the mention from The Listener's " Spoken Word" (.pdf) column for March 3rd, by Martin Armstrong:

(p. 399)

The clue to figuring this all out lies in that the seemingly ambiguous time references in The Listener. They're not ambiguous; they're rock solid. This Listener came out on Thursday, March 3rd, but covered broadcasting from Sunday, February 20th to Saturday, February 26th. Reed's 'broadcast on Hardy's poetry' falls in 'the previous week', even though it was broadcast only one day before "Thomas Hardy: a tribute from his friends."

Here is Armstrong's review of " The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: a study by Henry Reed," (.pdf) from The Listener of February 24th, 1955:

Thomas Hardy was a great English poet, but he wrote poetry as well as prose, or rather prose as well as poetry. On the previous evening Henry Reed gave an hour's discourse, with copious illustrations read by Mary O'Farrell, Michael Hordern and James McKechnie, on 'The Poetry of Thomas Hardy'. Listening to Mr. Reed I sometimes feel that I am back in the old classroom under the eye of one of the sterner and more intelligent of my schoolmasters and that if I were to venture a giggle or an independent view I would receive a disapproving glance. Nevertheless I enjoy myself and am the better for my lesson. Mr. Reed presented Hardy's poems in the light of his history, and this approach considerably enhanced one's appreciation of them. He suggested that a new edition of the poems is needed in which they run parallel with the biography—an admirable notion, it seems to me, but one that would involve a herculean job for its editor. The poems were excellently read by all three readers. Mary O'Farrell proved, if proof were necessary, that she is one of the two best women readers of poetry on the B.B.C. (p. 355)

Reed once had hopes of writing a biography of Hardy, and worked on this book on and off from the mid-1930s until the 1950s, when he finally gave in and gave up. These two, short broadcasts were the only tangible result of his 20 years of devotion and labor, his life's work. I sometimes also feel I am under the stern and disapproving eye of Mr. Reed, though sometimes, when I solve some particularly confounding problem, I feel him give me a wink.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

I'm sitting on a million-dollar idea. It's going to be the next Harry Potter, let me tell you. It's a Hardy Boys book, except instead of featuring boring old Frank and Joe, it chronicles the adventures of Thomas Hardy and his younger brother Henry: Tom and Hal Hardy, teenage sleuths in Victorian Dorset. Or maybe their adventures take place just before the publication of Tess of the d'Urbervilles. That would be contemporary to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and then Henry could play Dr. Watson to Thomas' Holmes, I can't decide. The Mystery of the Madding Crowd. The Clue Under the Greenwood Tree. A million bucks, I'm telling you.

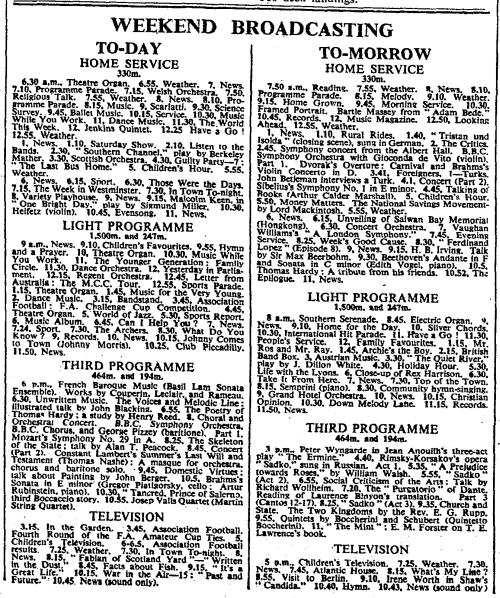

Maybe the Hardy boys could puzzle out this riddle: The Secret of the Two Radio Shows. In his chapter in British Radio Drama (John Drakakis, ed., 1981), " The Radio Plays of Henry Reed," Roger Savage mentions that in the 1950s, Reed presented "an anthology of recorded memories for the BBC called Thomas Hardy: A Radio Portrait by His Friends, observing that it is 'characteristic of a great deal of utterance on Hardy' that 'people prefer... to talk at length about themselves'" (p. 180). The Times' broadcast schedule for February 19th, 1955, lists two programs on Hardy that weekend (click for full size):

Under "To-day" (February 19, 1955), for the Third Programme: " 6.55, The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: a study by Henry Reed." Then, for "To-morrow" (February 20), there is listed on the Home Service: " 10.5, Thomas Hardy: A tribute from his friends." Which is the portrait mentioned by Savage? Either? Neither? The show following begins at 10.52, making the tribute only two minutes long. That can't be it.

Another clue comes from Michael Millgate, who sings Reed's praises in "The Hunter-Gatherers: Some Early Hardy Scholars and Collectors" ( Thomas Hardy: Texts and Contexts, Phillip Mallett, ed., 2002). Millgate refers to "a remarkable broadcast of 1955, made while [Reed] was working for the BBC, into which he incorporated the spoken reminiscences of Gertrude Bugler, Dorothy Allhusen, Robert Graves, May O'Rourke, Walter de la Mare, and several others who had known Hardy in his lifetime..." (p. 193). Surely Savage and Millgate are talking about the same program?

(Incidentally, I was set off on this mad quest by this audio recording of Walter de la Mare talking about meeting Thomas Hardy [BBC4, RealPlayer required], from April, 1955.)

I popped into the library on the way home from work tonight, and looked up a book called Thomas Hardy: Interviews and Recollections (James Gibson, ed., 2002), which mentions a BBC broadcast of February 19th, 1955, this time referred to as " Hardy and His Friends." Four excerpts from this broadcast are included, from: St. John Ervine, the novelist and playwright; Major General Sir Harry Marriott Smith; Llewelyn Powys, the writer (a single quote); and from May O'Rourke, who was Hardy's secretary during the final years of his life. Millgate specifically mentions O'Rourke as participating in Reed's broadcast, so it would seem that the Times' "study" is the program in question, though Gibson gives no credit or notation. Perhaps the title has gotten confused and concatenated.

I'll have to pull the Listener volume for 1955, and see if anything was written about the Hardy programs. Somewhere around here, too, I think I have a printout of the seventy-odd Reed broadcasts which were listed in the BBC's Programme Catalogue (before it went dark). Stay tuned! More Hardy Boys adventures to follow.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

Here's a taste of an article by Michael Millgate, famed Hardy biographer and Professor Emeritus at the University of Toronto (Millgate, previously). The article is titled "Sources," and it deals with the responsibility of biographers to obtain evidence for their subjects which is 'as direct, as specific, and as authentic as possible,' and the problems they face attempting to do so. The article is from the June/September 2006 issue of English Studies in Canada (p. 55-62):

Most literary biographers... are by the nature of things less likely to encounter their subjects in the flesh than to find themselves dealing with families, friends, executors, lawyers, agents, servants, and so forth, and such relationships can present difficulties of their own. My former colleague Richard Purdy, Thomas Hardy's distinguished and (let me assure you) always dignified bibliographer, kept a secret on-the-spot record of his important conversations with Hardy's widow in the years immediately following Hardy's death but was deeply embarrassed, so he once told me, by the need to excuse himself for the frequent washroom visits that gave him his only opportunities to jot down whatever had just been said. The English poet and playwright Henry Reed spent several years working on an eventually abandoned biography of Hardy and later drew upon that experience in an aciduously amusing radio play called A Very Great Man Indeed, dedicated to the proposition that the friends of the deceased, though ostensibly helpful, may prove in practice to possess not just defective or selective memories but their own personal agendas, ranging all the way from simple self-promotion to active revenge.

Researchers early in the field often have access—for good or ill—to just such a roster of first-hand and even intimate witnesses, what might be called the usual suspects. As time passes, however, deaths occur, and as new researchers enter the field they typically resort to rounding up a series of second-tier players much less closely connected to the subject. Thomas Hardy's reputation, for one, has suffered a good deal from the publication of belated interviews with townsfolk whose memories yield up little more than ancient gossip and with former servants still incapable, forty and fifty years later, of forgiving a great man's small tips.

That one-sentence summary of A Very Great Man Indeed is great: interviewees with 'their own personal agendas, ranging all the way from simple-self-promotion to active revenge.'

Thomas Hardy was fond of collecting newspaper stories, and according to Millgate he kept cuttings of some of his own interviews, but he wrote "Faked" or "Mostly faked" on many of them.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

A heartbreaking turn of events appeared this evening, in Michael Millgate's Letters of Emma and Florence Hardy (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996). In a letter dated December 7, 1936, Florence Hardy (then aged 57) mentions 'A young man from one of the universities visiting me a few weeks ago said that all the stories one heard were amusing yet the time might come when the nation would be tired of a comic Royal Family.' Millgate notes this "young man" was none other than Henry Reed. In 1936, Reed had graduated with an MA from the University of Birmingham, and he was compiling material and interviewing contemporaries for his planned biography of Thomas Hardy.

Later, Millgate produces a letter to Reed from Florence Hardy: To Henry Reed

max gate, | dorchester, | dorset.

25th Dec. (1936)

Dear Mr. Reed,

I have been thinking very long & seriously about the book we discussed when you were here, and the more I think about it the more impossible it seems. My own memory is not good & becomes worse & worse, & probably I have exaggerated in my own mind much that was told me, &, as for Miss [Katherine "Kate"] Hardy, she is an old lady in bad health, who has, during the last days lost her nearest surviving relative [cousin Polly Antell] & she will not see any stranger, nor will the doctor allow her her to do so. Moreover she would refuse to discuss any member of her family with anyone. It is possible that I built up a great deal on a few careless remarks from prejudiced persons. I should be very sorry to put into print more than is in my biography as there is not a scrap of documentary evidence to go upon.

Also, with regard to a stage version of 'The Dynasts'—I find that my husband left very special instructions about that, & any performance by amateurs, except the O.U.D.S [Oxford University Dramatic Society], is prohibited. I am sorry to be so negative on both these points, but I hope you will understand.

With seasonable wishes,

Yours sincerely,

Florence Hardy.

Reed's literary hopes and dreams were swept away in the span of two small paragraphs. According to Millgate's notes, the project Florence deems "impossible" was a biography of Thomas Hardy which Reed had suggested, to be based on his conversations with Florence and Hardy's cousin Kate. And apparently Reed was also hoping to adapt Hardy's epic verse-drama on the Napoleonic Wars, "The Dynasts," into a stage play, perhaps for the Highbury Little Theatre group, in Birmingham.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

Reed's freelance career with the BBC was more or less over before the demise of the Third Programme in 1970, and he would produce only a handful of translations for broadcast in the following years. Part of the problem was his reluctance, or inability, to adapt to the new medium of television. He had a disastrous experience working with the director Ken Russell on a film about the composer Richard Strauss in 1969-70. This is widely regarded as Reed's only foray into television.

I found a surprising story today in Sean Day-Lewis's memoir of his father, C. Day-Lewis: An English Literary Life (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980), which proves Reed dared to delve into television at least one time, previously. In 1963, Reed had a run-in in Dorset with his friend and fellow poet Cecil Day-Lewis, when both men were working on rival Thomas Hardy projects for TV:

Earlier that summer Cecil had done his work as commentator on a short film about Thomas Hardy made by David Jones for the bbc Television arts programme Monitor. He had said some of his piece at the Upper Bockhampton cottage, near Dorchester, where Hardy was born in 1840. By chance, the poet Henry Reed, the source of so many of the jokes on which Cecil dined out, was at the same time making a Hardy programme for Southern Television. Between them they built this coincidence up into a hilarious anecdote which had the lane jammed with outside broadcasting units, a sea of crossed wires and cross technicians, and the two poets shouting infuriated insults to each other, Cecil ponitificating indoors, and Reed holding forth in the garden. Whatever the difficulties, the bbc film was completed and broadcast at the end of November (p. 254).

Can't you hear the two men pouring derision at each other, playing it up for the cameras and crew? "Day-Lewis, you hack! Are you going to spend all day in there?" "We'll be through when we're through, Reed! You has-been!" That's a lovely compliment about Day-Lewis retelling Reed's jokes, too.

And here's a bit of film-and-tv trivia for you: the actress Kika Markham played Tess in the BBC's film (click on "reveal extra detail"). I recognize her from her cameo as Sean Connery's wife in the 1981 movie, Outland.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

I think, given the chance to do it over again, I'd rename this blog The Ghost of Hardy's Cat. (Indirectly, via Peter Stothard.)

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

'The aim of this project has been to reconstruct as fully as possible the contents of Thomas Hardyís library at Max Gate, his Dorchester home, at the time of his death in January 1928.'

"Thomas Hardyís Library at Max Gate: Catalogue of an Attempted Reconstruction," by Michael Millgate. I especially enjoyed the debacle of the bookplates. ( Index.)

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

Michael Millgate is a Hardy scholar. He may be the preeminent Hardy scholar, having written or edited innumerable biographies and collections. In several of these, he acknowledges assistance and contributions made by Henry Reed.

In 1936, Reed graduated from the University of Birmingham, having written his MA thesis on Thomas Hardy's early novels. Afterward, his plan was always to write a "Life of" Hardy. He called upon Hardy's widow, Florence, at their house in Dorset, Max Gate, and was given some access, at least, to letters and papers there.

Reed's goal was to create a biography based on recollections of those who had known Hardy, and to root out all the possible sources for his work. But this grand undertaking never came to fruition. Earning a living by reviewing books must have been difficult, and then there was the intervention of the Second World War. Finding success scripting radio plays for the BBC, Reed finally abandoned the biography sometime in the mid-1950s. The most he had to show for his labors was a 1955 Third Programme broadcast, "The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Study."

Millgate has contributed a chapter to Thomas Hardy: Text and Contexts (Mallett, 2002) called "The Hunter-Gatherers: Some Early Hardy Scholars and Collectors," which illuminates Reed's efforts and contributions to the field of Hardyana, and his correspondence with other scholars. This includes a reference to a letter from Howard Bliss to Richard L. Purdy, written in 1949, in which Bliss refers to Reed as Hardy's "Literary Biographer" (p. 199n).

That letter is in the Richard L. Purdy Collection of Thomas Hardy, at Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which contains every kind of Reed goodies: corrected galleys, typescripts, and proofs. The Beinecke looks like a gorgeous building with almost futuristic facilites: wouldn't it be a hoot to ride the train up to Connecticut for a looksee? Simple as a twelve-hour train ride.

Millgate concludes his piece with some sage advice, based on personal experience no doubt, for any scholar or collector making inquiries toward or visiting some private literary collection: ‘Anyone contemplating such a visit, however, should certainly write well in advance and try to remember to send a prompt thank-you letter afterwards. Upon arrival, it's well to wipe your shoes on all available doormats, express admiration and/or gratitude for your host's weak coffee, stale cakes, small sherries, and aggressive pets, and suppress any early expression of your personal views on religion, politics, and social issues generally. It's also important to try and open precious volumes without breaking their spines, to avoid leaving sweaty finger-marks on the manuscripts of Hardy poems or Keats letters, to reserve one's more intrusive requests until some degree of personal rapport has been established, and to think twice or indeed several times before seeking to ingratiate oneself with elegant connoissers or the owners of stately homes by gifts of cheap wine.’ Wouldn't it be marvelous if one day, some brash, young scholar knocked on your door, dragged in their muddy feet, offered you a bottle of last year's Merlot and smeared their ink-stained fingers all over your precious database?

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|

I'm sitting on a million-dollar idea. It's going to be the next Harry Potter, let me tell you. It's a Hardy Boys book, except instead of featuring boring old Frank and Joe, it chronicles the adventures of Thomas Hardy and his younger brother Henry: Tom and Hal Hardy, teenage sleuths in Victorian Dorset. Or maybe their adventures take place just before the publication of Tess of the d'Urbervilles. That would be contemporary to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and then Henry could play Dr. Watson to Thomas' Holmes, I can't decide. The Mystery of the Madding Crowd. The Clue Under the Greenwood Tree. A million bucks, I'm telling you.

I'm sitting on a million-dollar idea. It's going to be the next Harry Potter, let me tell you. It's a Hardy Boys book, except instead of featuring boring old Frank and Joe, it chronicles the adventures of Thomas Hardy and his younger brother Henry: Tom and Hal Hardy, teenage sleuths in Victorian Dorset. Or maybe their adventures take place just before the publication of Tess of the d'Urbervilles. That would be contemporary to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and then Henry could play Dr. Watson to Thomas' Holmes, I can't decide. The Mystery of the Madding Crowd. The Clue Under the Greenwood Tree. A million bucks, I'm telling you.