What eventually happens to the personal library of a preeminent 20th-century Irish poet and critic? It gets donated to the National Library of Ireland, of course.

Valentin Iremonger reviewed Reed's A Map of Verona for The Bell, in 1946. Iremonger's personal copy of Reed's book now resides in the National Library, and you can view records in their catalog for all the items in the Iremonger Collection, as well as a separate list of the original dust jackets removed from his books (for safekeeping, presumably).

|

Iremonger Collection

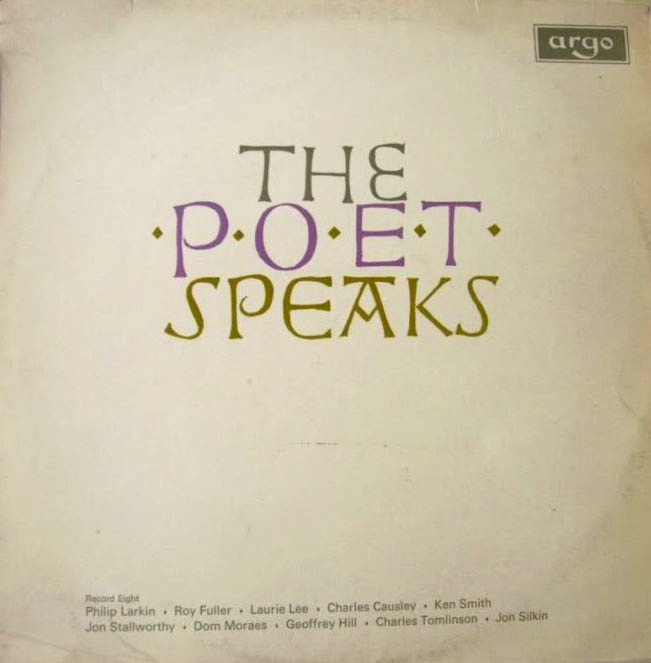

The Poet SpeaksIn the 1960s, the British Council teamed up with the Harvard Library Poetry Room to record contemporary British and American poets reading from their own work, and in interviews discussing poetry and the process of writing. English poets who participated in the project included John Betjeman, C. Day-Lewis, William Empson, Hugh MacDiarmid, Louis MacNeice, Kathleen Raine, Stephen Spender, John Heath-Stubbs, W.R. Rodgers, and Vernon Watkins, to name just a few. Interviews were conducted by Ian Scott-Kilvert, Hilary Morrish, Peter Orr (head of the British Council's Recorded Sound department), and John Press. A few details are mentioned in "Poetry, for Crying Out Loud," a 1999 Independent article.

The final product of these recordings was a set of ten LP records released by the Argo Recording Company, along with an accompanying book of transcripts called called The Poet Speaks: Interviews with Contemporary Poets (London: Routledge, 1966).  The project didn't end when the record collection was produced, however, because we can find recordings of a 1970 interview with Henry Reed, both at the British Library Sound Archive, and at Harvard's Poetry Room: "Interview with Henry Reed sound recording, by Peter Orr, British Council Recorded Sound Dept., June 11, 1970." Alas, the Reed interview was too late to get included in the Poet Speaks project. The Woodberry Poetry Room at Harvard has one of the largest collections of recorded poetry in the world. Sadly, they provide only a few links to select recordings on their homepage (and several of those do not seem to be working, currently).

Reed's Hardy ThesisHenry Reed graduated from the University of Birmingham in 1936 at the age of 22, with a Master of Arts degree. At the time, he was the university's youngest MA.

Reed's (147-page) thesis was on "The Early Life and Works of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1878" (library catalog), a copy of which now resides in the Thomas Hardy Collection of the Dorchester Reference Library, Dorset: Dorchester's Hardy Collection contains 'nearly 1,000 theses for higher degrees in typescript or microform,' as well as critical articles from various literary journals. It would seem likely that the University of Birmingham still has a copy of Reed's thesis, but if they do, they don't seem to have cataloged it.

Encyclopedic ReedLast week I was wondering about a perplexing snippet in Google Books, which implied that Reed had contributed to some unknown anthology, or collaborated on a larger work. I had a bit of a brainwave regarding keywords the next day, and managed to reverse engineer my way to the missing text (the secret phrase was "edited by"). The review in the Bookseller reads:

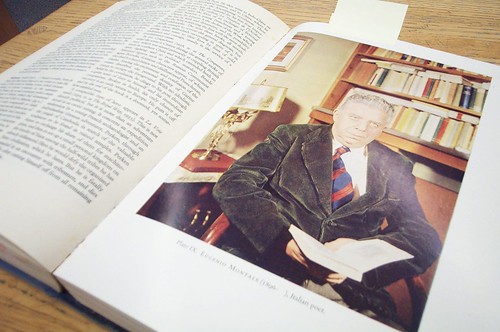

The Concise Enclyclopædia of Modern World Literature (50s.), edited by Geoffrey Grigson, which includes more than 300 articles on individual authors, and—to place them in their wider setting—articles describing the development of the major national literatures and characteristic literary forms of our time...[.] The contributors... were asked 'to write about what they had enjoyed, communicating their enjoyment without escaping into superlatives'. There is a complete author/title index, and general bibliographies. There are 16 pages of colour plates, 160 in half-tone. The London edition being prohibitively distant, I settled for a copy of the American edition of Grigson's Encyclopedia (New York: Hawthorn, 1963), just a short drive away, at a local public library: It's a beautiful book. Or, at least, it was beautiful in 1963. The reference copy I looked at had been ridden hard: the binding was torn and held together with book tape; the pages brittle and split on some edges. But the endsheets were still bright and colorful, and the entries lavishly illustrated (for an encyclopedia) with photographs, some of which I had never seen, including a picture of Louis MacNeice attending Dylan Thomas' funeral. Some thoughtful cataloger had even pasted the original front and back flaps of the missing dust jacket inside the front cover. In his editor's Introduction, Grigson explains his instructions to the contributors: Some writers — or some individual books — need rescuing from what is almost or entirely oblivion. Some have escaped attention because they are not easy to categorize. Bearing this in mind that 'literature' is not really so common, in spite of publisher's advertisements, contributors to this volume were asked to write about what they enjoyed, they were asked to communicate, in a level way, their enjoyment; and to avoid, in doing so, both superlatives and the various ways of evading literature. One way of our time is historical, so they were asked not to indulge in chatter about trends, influences, schools, traditions. They were asked for sensible dogmatism — at any rate, for the unequivocal statement, and (where space allowed) for quotation — i.e., some part of the substance of what they were writing about. Another way of evasion is biographical. They were asked to concentrate on the books of each author, not on his life (though a biographical fact may be relevant, Yeats, for example dreaming of Bernard Shaw as a sewing machine which smiled and smiled). Even then, contributors were asked to concentrate on the books which mattered, instead of giving the neutral itemized survey which you might expect from a conventional encyclopedia. (p. 11) (Yeats apparently had some difficulty digesting Shaw's Arms and the Man [1894]: 'Presently I had a nightmare that I was haunted by a sewing-machine, that clicked and shone, but the incredible thing was that the machine smiled, smiled perpetually.') Alas, although there is a full list of all the contributors at the front of the volume—and biographical notes on them at the back—the articles in the encyclopedia are not signed. So we must take Grigson's instructions to heart, and ask ourselves, "Whom did Henry Reed enjoy? Who was Reed uniquely suited to concentrate on and communicate about?" I made copies of the most likely suspects: Ugo Betti, almost certainly; Thomas Hardy, unequivocally; Montale and Montherlant, possibly; Pirandello? Maybe. Update: After looking at my scans (linked above), Ed (of I Witness) feels strongly that the Hardy article is not Reed's (and I must reluctantly agree). But Ed thinks that the Betti is a possibility, and Montale, likely. Thanks, Ed!

Former OwnerLook what turned up in the New York Public Library's Berg Collection of W.H. Auden material: Henry Reed's personal copy of Auden's Poems (1933). That's the second edition of Auden's first published poems from 1930, submitted to T.S. Eliot while he was at Faber and Faber.

The library catalog record states the copy 'contains ownership signature, "Henry Reed, 1943" on free endpaper'. That would mean this was a book Reed had with him during the war years, while he was stationed at Bletchley Park (previously). No word on whether there's any marginalia, however. The book was a gift given to the NYPL in June, 2007, from Eric H. Robinson. Could that be the Eric Robinson, historian and literary scholar, long claimant to the copyright (Guardian) of the poems of John Clare (1793-1864)?

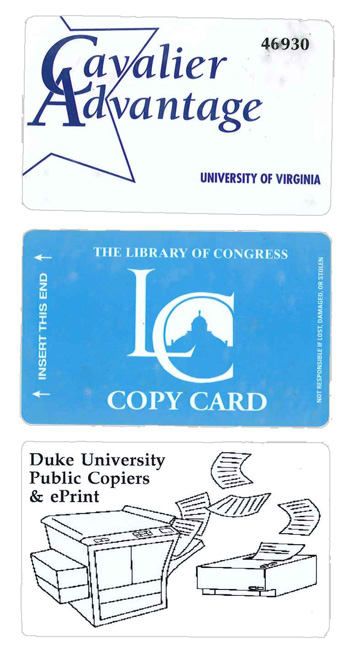

Investment PortfolioAll my money is currently tied up in photocopy cards:

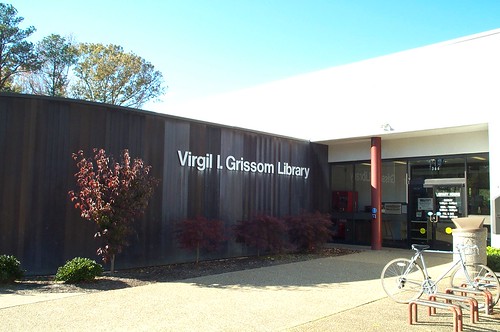

LibraryThing LocalLibraryThing (remember LibraryThing? We had a visit from Tim, back in the day) went live last week with a neat new app: LibraryThing Local. I don't usually Oo and Ah over stuff that's all Web 2.0ey, but this is pretty neat.

It's basically a mapping system which allows LibraryThing members to add "venues": libraries, bookstores, festivals, and other book-related locations and events. For instance, here's all the recently-added venues within five miles of The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. (zipcode 20540). Thingology has a post with a bunch of other examples. Users can bookmark their favorite spots, and libraries and bookstores can even officially sponsor the entries for their venues, if they didn't add themselves. Here's the LibraryThing blog announcement of the new service, and an update after the first 9,000 venues were added.

Books of FuryBecause we love libraries and cartoon violence in equal parts. "Books of Fury," featuring Buddhist Monkey vs. a pack of book-defacing scofflaw ninjas. (Highlighters? Nooooo!) An episode of mondo media's Happy Tree Friends.

Collected, At LastHere's an interesting bit of trivia: a Collected Poems of Henry Reed was proposed as early as 1979, seven years before his death.

The Archive of Carcanet Press is housed in the John Rylands University Library at the University of Manchester. The collection contains communications to and from Carcanet's editors, authors, and critics. In correspondence from between April 1979 and May 1980, editor Michael Schmidt, co-founder of the Press, and David Jesson-Dibley, go back-and-forth about current, possible, and future projects: Much of this relates to Robert Herrick's Selected poems, edited by Jesson-Dibley as part of the Fyfield series and published in 1980. Includes references to: Schmidt's initial suggestion that Jesson-Dibley undertake the project, and suggestions put forward by both men of potential poets for Jesson-Dibley to edit; the possibility of editing a Fyfield volume of Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury's verse; Jesson-Dibley's suggestion of a volume of lives and anecdotes of seventeenth-century poets; the ultimate selection of Herrick, and plans for the book's content and arrangement; his progress; and the contract. Other topics include: Jesson-Dibley's attempts to find a publisher for a novel he has written and Schmidt's advice on this; the possibility of Carcanet undertaking a Collected Poems of Henry Reed; a play Jesson-Dibley has completed called Ahab and his neighbours; his other work, including some teaching; and Schmidt's book An introduction to fifty modern poets (1979). I tracked down the library's copy of Fifty Modern British Poets, hoping that Schmidt may have granted Reed a special place among the lives of his peers. But all I found was a small, disappointing note in the editor's Preface: 'Had I been able to include sixty poets, I should have added essays on Robert Bridges, Arthur Symons, John Masefield, Siegfried Sassoon, Norman Cameron, Henry Reed, Seamus Heaney, Alun Lewis, Peter Scupham, and Roy Fisher.' In his book Reading Modern Poetry, Schmidt asks: 'Will Henry Reed ever be more than an anthology piece and a brilliant parody?' We'll see. Carcanet inherited Oxford University Press's Oxford Poets list in 1999, following OUP's decision to drop contemporary poetry. There is a glimmer that Carcanet intends to reissue Reed's Collected Poems as a paperback in 2007, bringing the book full-circle.

Gleanings from the Sound ArchiveThe British Library Sound Archive lists 47 titles under the author heading "Reed, Henry, 1914-1986." I suspect there are a few more skulking about, which were cataloged with different headings. Somewhere around the apartment I have a printout, intending one day to go over it record by record, and sort out their holdings.

A curious visitor emailed me this week (thanks, Nancy!), and happened to bring to my attention an entry in the Sound Archive catalog for a 1970 recording of "The Complete Lessons of the War." I'd never heard of such a version. There it is, however: Item notes: A sequence of poems by Henry Reed. The fifth poem, Returning of Issue, has been largely rewritten since the programme was first broadcast in 1966. This new version has been re-recorded.A quick search of the broadcast schedule in the London Times confirms a rebroadcast on that Thursday, at 10:00 p.m. That's not even the most amazing thing. While I was poking around in the chaos of the Sound Archive (three entries for each item, Work, Product, and Recording?), I saw a title I didn't recognize: "On the Terrace." The item notes describe the recording as being from the BBC program "Poetry Now" on November 2, 1970, introduced by producer R.D. Smith. There is no poem entitled "On the Terrace" in the Collected Poems and, while there are undoubtedly many unpublished poems in Reed's personal papers, the collection description at the University of Birmingham does not mention this particular poem. Was it a piece Reed was trying out, but, ever the perfectionist, eventually abandoned? Is it one of his many translations? Did he change the title? 1970 was late in Reed's poetic life, but a time in which he seemed to rise from his long silence, publishing several poems in The Listener, and at last releasing the complete Lessons of the War in print.

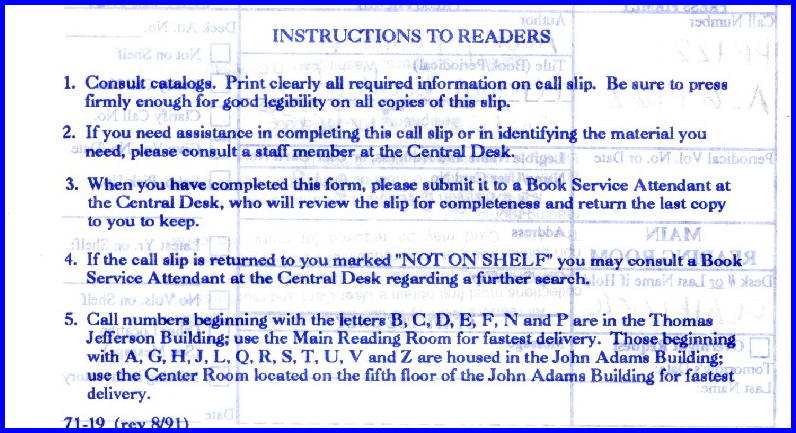

A Scholarly Adventure, Part IIAphorism: Everyone at Library of Congress is working on something more interesting than you. Everywhere I went — the elevators, the halls, Photoduplication Services — people were talking about their research, and each topic was infinitely more exciting and erudite than my little project.

In the elevator, there was a gentleman who casually mentioned his dissertation was on race relations in an exotic country during some dimly-remembered century. At the photoduplication desk, it was a lady who was ordering full-size copies of pages of the London Times, to be shipped to a friend in New England. And in the Adams reading room, an affable fellow across the table was impatiently awaiting a journal containing an article concerning cellular automata (Wolfram's A New Kind of Science was recommended as a starting point). Myself? I had travelled several hours by car and by train to make copies of old t.v. guides. Well, okay. Not actual T.V. Guides. I was looking for issues of the BBC's Radio Times which immediately preceded broadcasts of Henry Reed's radio plays. I had seen few, scattered mentions of articles written by or about Reed, notably in Roger Savage's unrivalled chapter in British Radio Drama (Drakakis, ed., 1981); The Diversity Website's "Henry Reed radio drama" page; and poking around the inventories of dealers in rare back issues of U.K. magazines. The Library of Congress is a venerable institution. Venerable and inveterate. Waved through metal detectors by uniformed security (please place your cellphone on the X-ray machine's conveyor, not in the plastic bin with your keys), you must shed your coat and bag at the cloakroom, and proceed to the reading rooms without the benefit of the protective layers to which you are accustomed, a naked scholar. You fill out your slips requesting your obscure volumes, and the desk attendant roughly crams them (along with everyone else's) into a small brass cylinder about the size of can of tomato paste. The cylinder disappears into a pneumatic tube and is whoooshed away into the bowels of a national library that occupies three city blocks. Now you have about an hour to study and memorize the intricately carved and muraled ceilings (you notice a predominant theme on owls), near the end of which you will suddenly realize that you failed to fill out a slip for the single volume on which your day's research will hinge. Then you will hear a distant rumble, a shudder or deep vibration — like the building is directly under the landing path of an international airport — and an ancient dumbwaiter bearing the immovable weight of your books rises, rises behind the counter, and in a moment, the attendant bears them lovingly to your desk. He makes two trips. Some of the resulting .pdfs: "Captain Ahab and the Great White Whale." (Moby Dick). "The Prisoner in the Palazzo." (The Unblest). "Did Shakespeare Go To Italy?" (The Great Desire I Had). "Homage to Dame Hilda — Or Swann's Way." (Musique Discrète). I learned a few things: 1) Reader Identification cards expire every two years. 2) At the cloakrooms, you can request a clear, see-through, plastic bag to tote around your notes and pencils and photocopies without being a security risk. They won't let you in the reading rooms with an accordian file or manila envelope. 3) If you are unsure about the library's run of holdings for a certain periodical, put in requests for your earliest and most recent cites first. See what comes back. 4) The Folger Shakespeare Library is right next door to the Adams building. You can put in your book requests and while away the hour's wait worshipping before a First Folio. 5) Smoking is not allowed anywhere within 50 feet of federal buildings. An ashtray is located approximately 51 feet from the entrance to federal buildings. 6) There is nothing more mysterious and heartbreaking than having your original request slip returned with an X in the dreaded "Not on Shelf" box. Not on shelf? Why? Was it something I did? Something I said? Where is it? It could be many places, but it was decidedly not on the shelf where it resides when it is. On the shelf. And 7) The Washington Monument is huge. It's 554 feet tall. Standing just outside the main entrance to the Madison building, in the shadow of the U.S. Capitol, the obelisk looms on the horizon, seemingly just a short stroll away. It's not. It's a mile and a half, with a backpack full of books and index cards and $20.00 worth of photocopies, warm as newly baked bread. (Read Part I....)

Sitting of the FishesWith the university on Winter Break, students are always looking for some kind-hearted soul to care for their pet fish. Problem is, most people who would normally volunteer for such a job usually also go away for the holidays. Solution? Library fishsitting service!

Stale Cakes, Small SherriesMichael Millgate is a Hardy scholar. He may be the preeminent Hardy scholar, having written or edited innumerable biographies and collections. In several of these, he acknowledges assistance and contributions made by Henry Reed.

In 1936, Reed graduated from the University of Birmingham, having written his MA thesis on Thomas Hardy's early novels. Afterward, his plan was always to write a "Life of" Hardy. He called upon Hardy's widow, Florence, at their house in Dorset, Max Gate, and was given some access, at least, to letters and papers there. Reed's goal was to create a biography based on recollections of those who had known Hardy, and to root out all the possible sources for his work. But this grand undertaking never came to fruition. Earning a living by reviewing books must have been difficult, and then there was the intervention of the Second World War. Finding success scripting radio plays for the BBC, Reed finally abandoned the biography sometime in the mid-1950s. The most he had to show for his labors was a 1955 Third Programme broadcast, "The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Study." Millgate has contributed a chapter to Thomas Hardy: Text and Contexts (Mallett, 2002) called "The Hunter-Gatherers: Some Early Hardy Scholars and Collectors," which illuminates Reed's efforts and contributions to the field of Hardyana, and his correspondence with other scholars. This includes a reference to a letter from Howard Bliss to Richard L. Purdy, written in 1949, in which Bliss refers to Reed as Hardy's "Literary Biographer" (p. 199n). That letter is in the Richard L. Purdy Collection of Thomas Hardy, at Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which contains every kind of Reed goodies: corrected galleys, typescripts, and proofs. The Beinecke looks like a gorgeous building with almost futuristic facilites: wouldn't it be a hoot to ride the train up to Connecticut for a looksee? Simple as a twelve-hour train ride. Millgate concludes his piece with some sage advice, based on personal experience no doubt, for any scholar or collector making inquiries toward or visiting some private literary collection: ‘Anyone contemplating such a visit, however, should certainly write well in advance and try to remember to send a prompt thank-you letter afterwards. Upon arrival, it's well to wipe your shoes on all available doormats, express admiration and/or gratitude for your host's weak coffee, stale cakes, small sherries, and aggressive pets, and suppress any early expression of your personal views on religion, politics, and social issues generally. It's also important to try and open precious volumes without breaking their spines, to avoid leaving sweaty finger-marks on the manuscripts of Hardy poems or Keats letters, to reserve one's more intrusive requests until some degree of personal rapport has been established, and to think twice or indeed several times before seeking to ingratiate oneself with elegant connoissers or the owners of stately homes by gifts of cheap wine.’Wouldn't it be marvelous if one day, some brash, young scholar knocked on your door, dragged in their muddy feet, offered you a bottle of last year's Merlot and smeared their ink-stained fingers all over your precious database?

The Diction of BrothelsI'm ashamed to admit it, but while my mother lay in hospital, I went to the local library. It sounds bad when you say it out loud. Someone asks, "Hey, what are you doing here?" and you have to reply, "Well, my mom's in the hospital, y'know, so I had time to photocopy some citations."

I was looking for a biography of Joe Randolph Ackerley, a former editor of the BBC's magazine The Listener, author and memoirist. I knew from a collection of his letters that Ackerley and Reed were friends, so I felt sure that A Life of J.R. Ackerley (Parker, 1989) would probably turn up something. Boy, did I ever hit paydirt (practically an anthill)! The Mary Jane and James L. Bowman Library is a branch of the Handley Regional Library system. It's a relatively new building, built on donated lakefront out in the boonies of Frederick County, Virginia. I'd never been, but from previous research I knew they had a copy of the biography. Since my mother was sleeping about 20 hours a day in the hospital, I pocketed all the loose change for the copiers that I could carry, and dropped by during a long lunch. It was well over 90° outside, and the library sat baking in its own parking lot, with nary a tree to shade a weary traveler (or a weary traveler's car, which currently is without a working air conditioner). In construction, the building reminded me strongly of an industrial chicken coop. Perhaps that was what the architects were going for. Of course the book was on the shelf: BIO ACKERLEY. (Ah! Dewey Decimal, how I miss thee!) I cracked it open to the index, first thing. Reed is only mentioned on about six pages, and I wasn't hopeful. But right off, the first page revealed a juicy tidbit: Ackerley was forced to fight to get Reed's poem "Sailor's Harbour" published, because it contained the word "brothels": We watch the sea daily, finish our daily tasksWhich is exactly the sort of playful, irreverent humor that makes Henry Reed terrific. Ackerley probably thought the "churches" line was great fun. Listener editor A.P. Ryan, however, arguing that this was not the sort of poetic language they were seeking to publish, wanted Reed to change "brothels" to "movies" (pp. 185-86). As far as I know, the poem never did appear in the pages of The Listener, but Reed seems to have befriended Ackerley because of the row. Later, Reed pops up again at Ackerley's farewell send-off from the magazine (which he refers to as his "funeral party"). Ackerley wrote in a letter: '...it was jollier than expected and went on until 8:30. The ebbing tide of distinguished guests had left behind them only a Corke and a Reed, and those I took off to dine. It was my last expenses sheet' (p. 352). The Corke can only be the poet Hilary Corke. It was October 29, 1959. One disturbing fact cropped up, related to Reed only tangentially: apparently at some point, efforts were made to purge the ranks of The Listener of homosexuals. Geoffrey Grigson is quoted: “Did I ever know a virtuous literary editor? Did I ever know one with an unfaltering conscience, a literary editor, a single literary editor, not given to compromise or betrayal? One. Joe Ackerley, of The Listener, whom some of his older colleagues in the BBC did their best now and again, to get rid of, in part, I imagine, because they knew him to be homosexual” (p. 182).The footnote mentions that Ackerley was once 'saved only by E.M. Forster's direct intervention with the Director-General of the Corporation.' Ackerley was certainly open about his sexuality in his memoirs, and his fiction also handles homosexual themes. I sometimes wonder about our friend Henry, and how overt or obvious he may have been, what troubles it may have caused him, and whom he trusted. I know of several stories in which people, strangers and acquaintances, didn't know he was gay. A fact which seemed to simply amaze him, as if it were the most obvious thing in the world.

The Perils of Interlibrary LoanThree weeks ago, I put in for an interlibrary loan to get some photocopies of a book review from an old issue of The Listener.

Our Interlibrary Loan department states that getting photocopies may take a week to ten days. Usually, requesting a book or copies from another library takes less time, especially if it's from another in-state library. But ILL makes no promises. We must still rely on the unpredictable services of the U.S. Mail. Anyway, two weeks after I submitted my request, I started to worry. "How long do I have to wait before I get to complain?" I asked. It's a free service, so complaining about how long it takes is really ungrateful. But ILL re-sent my request to another library. Duke University's Perkins Library came through, finally. They even emergency-faxed the pages, which made up for some of the lost time. But somewhere along the line my request got manhandled or mistranslated: they missed the journal issue's table of contents, and they copied the title page from the first issue in the volume, not the title page from the issue my article was in. Oh, well. Beggars, choosers, and all that. Still, even I know how to tell the difference, and I know what TOC stands for. And what ever happened to my original request? Was it sent, and is malingering and maloitering under some Post Office conveyor? Did it ever get sent at all? Maybe, eventually, it will turn up, torn, opened and resealed, criss-crossed with tireprints, stamps cancelled and re-cancelled in foreign lands. Macht nichts. I had to dig up the full citation to fill out the ILL form. So, there you have it. The long, perilously dull, but true, story of the return of a very favorable review.

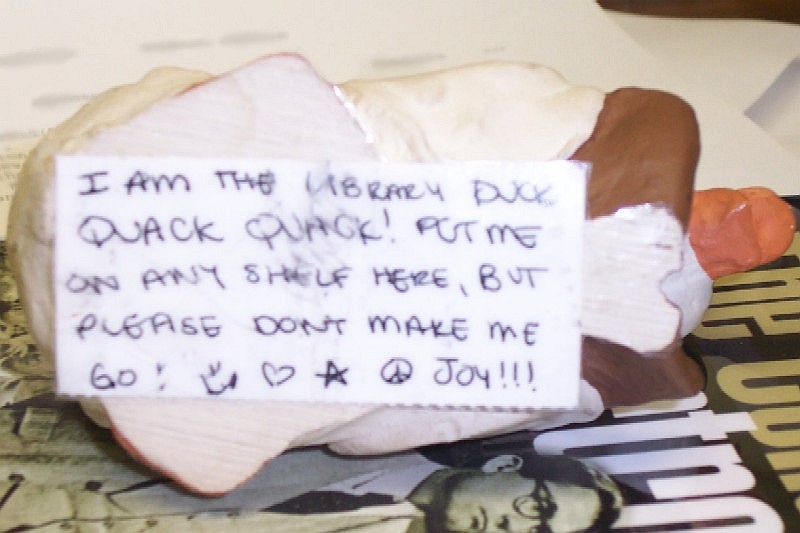

Library DuckA little-known tradition in our library is the Library Duck. I think, technically, it's a goose, but small matter. It's obviously a library duck, since it's reading a book. The pom-pommed hat is sort of inexplicable, though. The note on the bottom was written on the back of a ticket stub from Lost in Translation, so the Library Duck is hardly what you'd call a "time-honored" tradition. But I honored the sentiment: rubber-glued and re-taped the label, and put the Library Duck back in the stacks.

Pre-Easter LibraryingSummoned "home" for the holiday weekend, I managed to squeeze in a quick visit to the Alson H. Smith, Jr. Library at Shenandoah University to look up a music-related citation for Elisabeth Lutyens, before the place locked up early for chocolate bunnies and jelly beans.

The book, A Pilgrim Soul, reveals that Lutyens briefly considered suing Reed in 1954 for his satirical portrayal of the Lutyens-like Hilda Tablet. Especially interesting, this is one of the only places which mentions Reed's collaboration on Lutyens' BBC-commissions Canterbury Cathedral (1950) and Westminster Abbey (1953).

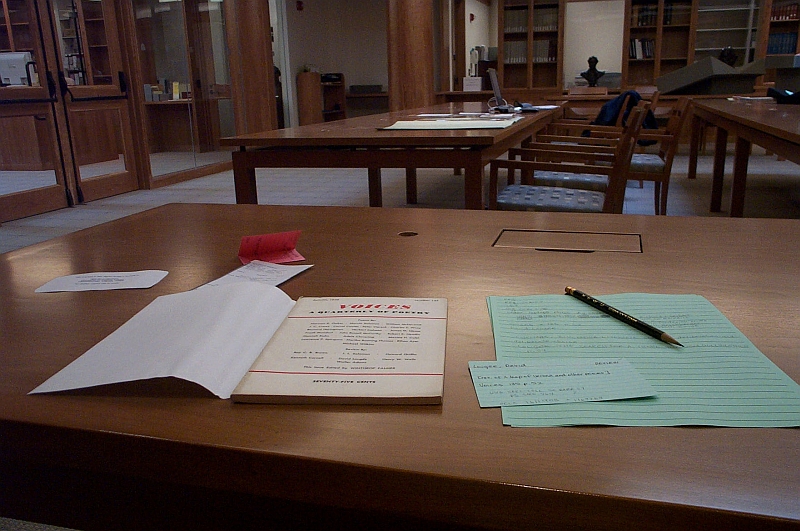

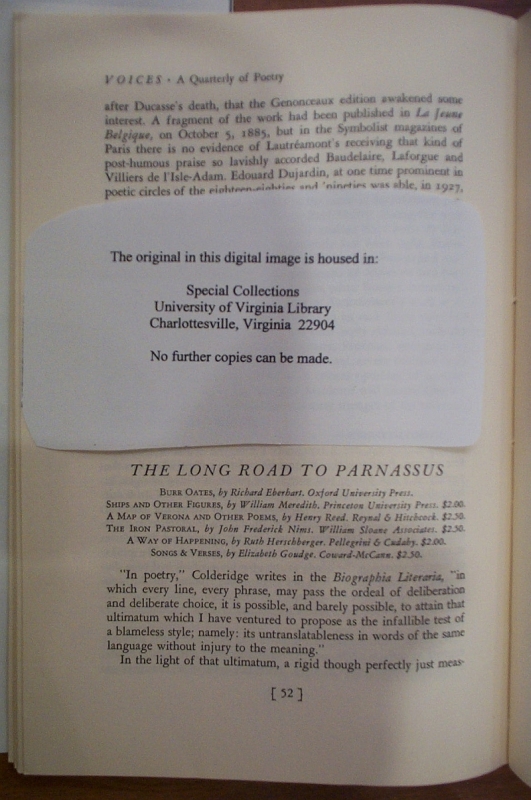

Library of DoomYesterday, I drove two hours west to the campus of the University of Virginia, just to get my hands on a three-paragraph book review from 1948. This is, aside from the occasional bicycle ride, the only hobby I have worth mentioning (if you can call questing to every library in a three-hundred mile radius a hobby). I'd been to the library at UVA before, when I happened to be in Charlottesville to visit friends or my big little brother, but yesterday was the first time I decided to make a day of it, pack a lunch. It's fall break at the university, which meant fewer students but shorter hours, and it was all the excuse I needed.

I planned like for an expedition to a jungle temple in Central America: I called ahead to check the hours for special collections, and ensure availablity. I had the nice folks at offsite stacks deliver a particular volume to the main branch (which meant setting up a user account for me, right over the phone. Sweet). I pulled all my notecards for 1940s and 50s journals, and jotted down the call numbers for odd memoirs and anthologies. I printed driving directions, maps, floorplans and cross-sections of the library. Took money out of savings, gassed up the wagon, and topped off the windshield-wiper fluid and coolant. Sharpened pencils. I even filled a Ziploc baggie with dimes to feed the photocopiers. But by far the smartest thing I did was pack along my digital camera (click for bigger):  Alderman library, University of Virginia, center. The new Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections building is on the left. Campus was nearly abandoned: just a few straggling students playing catch up, hoping to get ahead for the second half of the semester; moms and dads down for the weekend, getting the 25¢ son-or-daughter tour. (Is that Monticello? No, Ma. That's not Monticello. Oh. Is that Monticello?) Special Collections was the highlight of my day. They just moved into new facilities, and the building sparkles. Carpenters were still outside, putting finishing touches on cornices and window details. There's a grand, winding marble staircase inside that descends two floors, to the oak-trimmed reading room. The staff were still learning the new procedures, but the ladies were courteous and extremely helpful, walking me through each step to get the material I needed: register, request the volume online through the catalog, backpack goes in a bus station coin-op locker, sign in, pencils only in the reading room, please. A few minutes wait, and a 1948 issue of voices was delivered to my table, directly. It was unclear whether or not I'd be allowed to request photocopies of the article I was interested in, but I noticed another gentleman in the reading room taking digital pictures of some old, fragile maps, inked by Thomas Jefferson's personal assistant, probably. (Except for his bookishness, this gentleman looked like a spy in some James Bond flick, leaning over documents, clicking away, his camera charge annoyingly beeping its readiness to take the next image.) I asked if it would be all right if I did the same thing, and bam! Permission granted. I had only packed the camera to document the expedition, and ended up with a memory card full of (slightly blurry) pictures of a fifty-year-old book review. And because I am an inveterate, consummate researcher (read: anal-retentive perfectionist), I also spent twenty minutes copying out the relevant paragraphs, longhand. (On the green, ruled paper provided for me, specially!) You know you're a geek when you start describing italics and other Font-Variants in longhand. The rest of my day was spent in Alderman (hey, look: David Sedaris is reading in Charlottesville later this month!), blissfully bathed in the whitehot light of the photocopiers, deciphering the cryptic locations of coded call numbers, tracking the Borgesian trail of letters and decimals around corners and down long walls of stacks, navigating the narrow, sarcophagus-like stairwells between floors. Alderman is built into the side of a hill: the front entrance is actually on the fourth floor, and the majority of the collection is underground on three sides. They even have middle floors-between-floors, like in "Being John Malkovich." going downstairs you pass 3M... 3... 2M... 2... 1M... until finally hitting rockbottom level #1. I have to mention, despite the claustrophobically-low ceilings, that the stacks were sufficently lit and the books were remarkably well-ordered (which means either the staff are particularly hard-working, or the sections I was in don't get used much). By about three o'clock I knew I wasn't going to get everything done in one day. I reshuffled my pile of citations, prioritizing by need and by speed. secondary sources went straight to the bottom of the pile. Rising to the top were reviews and poems written by my author, in old, british journals located way down in the unsubbottombasement. The journals were unbound, printed during or following the second world war on rotten, yellowing woodpulp, brittle as peanut candy, tied together into bundles of years with string. There, I encountered my only disappointment of the day: a poem had been razored out by a disrespectful vandal, forming an impromptu Burroughs cut-up, words on two adjacent pages running together to make sensical nonsense. Them's the breaks, Indiana Jonesing the Library of Doom: sometimes, some dirty collaborating Belloq gets there first. Despite the fact that now i must seek another library with that particular volume of that particular journal, it was sort of cool, reassuring even, to find that someone had beaten me to it. That someone else had liked it enough to clip it when they read it, that it meant so much to them they would take the elevator down six floors to the basement of the library, just to steal a poem.

14 Things I Learned Researching at Library of Congress

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||