|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "RareBooks"

|

|

|

27.7.2024

|

Periodically, I browse listings for used (and sometimes rare-ish) books on AbeBooks.com, looking for items by, or relating to, Henry Reed. My best find, I think, was turning up Reed's personal copies of Moby Dick and Tristram Shandy at a used bookstore in Birmingham, UK.

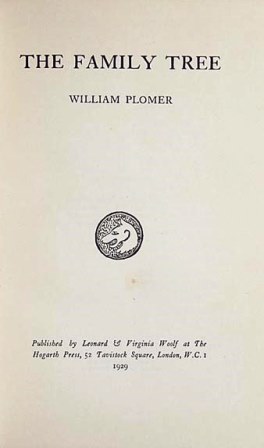

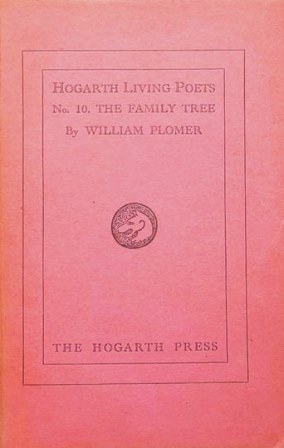

An amazing new treasure has appeared for sale, but one that leaves me conflicted as a poor, armchair researcher: a listing for a presentation copy of William Plomer's second collection of poems, The Family Tree (London: Hogarth Press, 1929), inscribed on the front endpaper to Henry Reed. These are the relevant parts from the bookseller's description:

††  [ Stock images.] Presentation Copy from the author to Henry Reed. 8vo. orig pink paper-covered boards printed in black, 106 pp. + "advertisement" (i.e. excerpts from reviews) page "of Mr. Plomer's Previous Volume of Verse, Notes for Poems"... First edition, limited to 400 copies, Leonard & Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press, London, 1929. This is a very special copy, inscribed to Henry Reed from William Plomer on f.e.p. William Plomer has also made some important alterations to text in purple pen with another long inscription on blank p.10 commenting that he will not reprint "The Family Tree" as it is of no interest as poetry... A wonderful unique copy. William Plomer CBE, 1903-1973, poet, novelist, literary editor; editor of some of the James Bond books for Cape, and librettist for Benjamin Britten. Reed and Plomer didn't know each other at the time the book was published, in 1929. If had to wager, I'd guess Plomer gave the book to Reed sometime between 1945 and 1949. Durham University Library has 11 letters from Reed to Plomer from during that time. Reed mentions having read Plomer's autobiography, Double Lives, in 1946, and reviewed an edition of Melville's Billy Budd in 1947 with an Introduction by Plomer. Plomer was a reader at Jonathan Cape in London, and was probably responsible for getting Reed's A Map of Verona: Poems published in 1946.

The bookseller is in Knighton, Wales, west of Birmingham, so the book has stayed in ó or drifted back to ó Henry Reed country. It is, indeed, a "very special," "wonderful unique copy," but the asking price gives me pause, however, as it's about the same amount as a month's rent for me. It would, however, give me a third book from Reed's personal library, which would be pretty exciting.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

What eventually happens to the personal library of a preeminent 20th-century Irish poet and critic? It gets donated to the National Library of Ireland, of course.

Valentin Iremonger reviewed Reed's A Map of Verona for The Bell, in 1946. Iremonger's personal copy of Reed's book now resides in the National Library, and you can view records in their catalog for all the items in the Iremonger Collection, as well as a separate list of the original dust jackets removed from his books (for safekeeping, presumably).

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

Maggs Bros., Ltd., is a London-based rare book and manuscript dealer, in business for over a century and a half. Here, in their inventory, is a listing for catalogue 1446, " Books from the Library of Douglas Cleverdon, 1903-1987." Cleverdon was a small press publisher and BBC radio producer. If you are a font-fanatic, you might be interested to know that Gill Sans, designed by Eric Gill, was originally created for the signboard over Cleverdon's bookshop in Bristol.

Among his credits as a radio producer, Cleverdon was responsible for the adaptation of David Jones's In Parenthesis (1948); Henry Reed's Italia prize-winning drama, Return to Naples (1950); Dylan Thomas's Under Milk Wood (1954); as well as all the plays in Reed's seven-part Hilda Tablet sequence (1953-1959). All in all, Cleverdon produced over two hundred programs for the BBC.

There's a fine article by Alex Hamilton on Cleverdon's achievements, "The Third Man," in The Guardian from November 20, 1971, which accompanied a profile on Henry Reed for the publication of the Hilda plays.

The Maggs Bros. catalogue, which is from 2010, includes this item:

54 REED (Henry). Returning of Issue. 54 REED (Henry). Returning of Issue.

Original heavily corrected manuscript and heavily corrected typescript of the fifth and final poem in Henry Reedís The Complete Lessons of the War series, inscribed by Reed: "To Douglas & Nest Cleverdon with love and gratitude Henry Reed, July 29, 1965". With a note from Henry Reed confirming Cleverdonís ownership of the manuscript and a note from the BBC allowing this gift from Reed to Cleverdon. £4000

Together with 23 TLS and ALS from Reed, predominantly to Douglas but with a couple to Nest and one to their elder son Lewis. Mostly in the mid 1960s and about radio drama and poetry by Henry Reed and the BBC but with 7 from 1950-51, also about Reedís radio work. One is in the character of the spinster "Emma Titt-Robbins", Tablet was the protagonist of Reedís satire The Private Life of Hilda Tablet, broadcast in 1954.

The catalogue also includes Cleverdon's personal, inscribed copy of Reed's poems, A Map of Verona.

I don't know if anyone snapped up the Reed manuscripts and letters back in 2010, but if I had £4000 pocket change, I would donate them to the University of Birmingham's Special Collections, to go with rest of Reed's papers and manuscripts.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

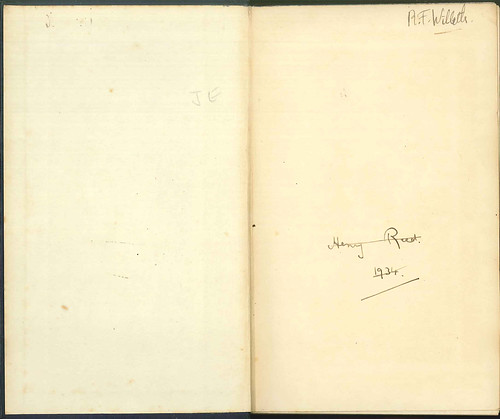

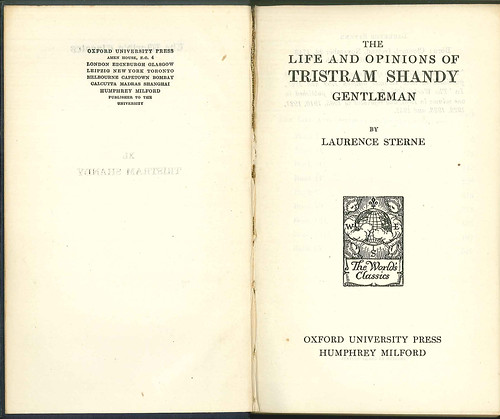

Henry Reed's personal copy of Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy (London: Oxford University Press, 1931), inscribed '1934' and crossed out. Subsequently (?) owned by the poet and classics scholar, R.F. Willetts (1915-1999), Professor of Greek and Chairman of the School of Hellenic and Roman Studies, University of Birmingham.

See previously, " Reading Moby Dick in Birmingham."

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

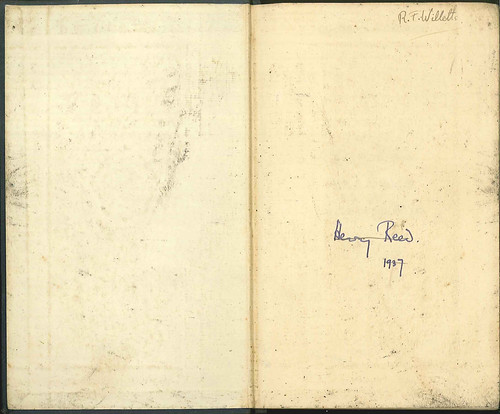

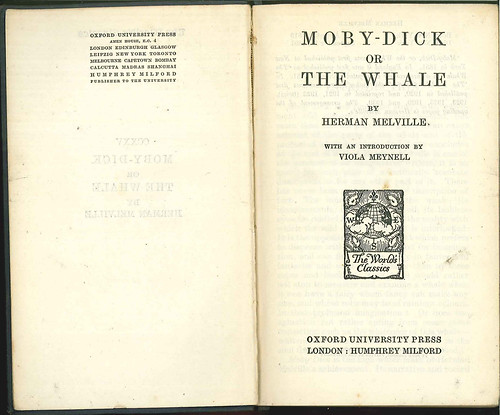

When I saw it advertised online I was by turns at first skeptical, and then conflicted: " Moby-Dick or, The Whale, by Herman Melville. London: University of Oxford Press, 1930. 676 pages plus a 16-page list of the Worlds' Classics—of which this is one; bound in dark blue cloth. Somewhat soiled on the covers and front endpapers. The free endpaper has the signatures of the poets Henry Reed (1937)—crossed out—and R.F. Willetts."

A quick search revealed that Ronald Frederick Willetts had been a Professor of Greek at the University of Birmingham. The bookseller was also in Birmingham. It would seem to be the right Reed. I felt, however, that buying this little piece of history would turn me into a Collector, capital "C". Perhaps I should leave the book in Birmingham for someone else? For a month the book languished in my online shopping cart, unpurchased, while I wrestled. In the end, avarice won the day. So here we have it, Henry Reed's personal copy of Moby-Dick:

Disappointingly, besides the two inscriptions, there is no marginalia or other marks. The silk bookmark is threaded between pages 14 and 15, in the first chapter, "Loomings":

Why did the poor poet of Tennessee, upon suddenly receiving two handfuls of silver, deliberate whether to buy him a coat, which he sadly needed, or invest his money in a pedestrian trip to Rockaway Beach? Why is almost every robust healthy boy with a robust healthy soul in him, at some time or other crazy to go to sea?

It seems unlikely—though still entirely possible—that this is the exact copy which Reed referred to when composing his radio adaptation of Moby-Dick for the BBC Third Programme (first broadcast January 26, 1947), much of which was written while Reed was living at Lovell's Farm, in Dorset. How the book came into the hands of Professor Willetts I can't say, but the two men traveled in much the same circles and it certainly seems likely that they would have known each other.

Ronald F. Willetts and Henry Reed were born a year apart—Reed in 1914 and Willetts in 1915. Both men were distinguished scholars and published poets. They attended the University of Birmingham in the 1930s, Reed going up in 1931 and Willetts in 1933; both read Classics under Professor E.R. Dodds, and studied Greek with Louis MacNeice during his tenure there. Reed took an MA in 1936 but was considered precocious; Willetts graduated in 1939. Both taught school before being called up for service during the Second World War. After the war, Reed went on to London to write for the BBC, while Willetts returned to Birmingham where he lectured in Greek until his retirement in 1981. It doesn't seem too far a stretch to believe that this book was a gift or loan.

Reed would seem to have been an admirer of Melville, in general. Besides his radio version of Moby-Dick, we also have him suggesting to Helen Gardner that Redburn may be a possible source for Eliot's "The Dry Salvages." The original working title of Reed's 1954 radio play Emily Butter was "Milly Mudd," and was envisioned as an all-female spoof of Benjamin Britten's operatic version of Billy Budd.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

Here's something not often seen in the wild: a 1956 reprint of Reed's A Map of Verona (London: Jonathan Cape). Though he only published this one volume of poetry, it remained in print for almost a quarter of a century, from 1946 until its last reissue in 1970:

Note the new dustjacket design (compare covers over on my Flickr page). This copy is for sale on AbeBooks.com by S. Edmonds Harrell, Book Services.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

In 1941, the Welsh poet Keidrych Rhys edited an anthology of poetry solicited from men and women in all branches of British military service, Poems from the Forces: A Collection of Verses by Serving Members of the Navy, Army and Air Force. Among the contributors were officers in the Royal Navy, aircraftwomen of the W.A.A.F., and even prisoners of war. The book was closely followed by More Poems from the Forces, in 1943.

Google Book Search has a limited preview of More Poems from the Forces, which includes a large selection from our very own Pvt. Henry Reed, R.A.O.C. The preview provides for at least partial views of "Naming of Parts," and "A Map of Verona," as well as Reed's lesser-known "Lives," "Tintagel" (later retitled "Tristram"), and "Hiding Beneath the Furze."

You can see several wartime photographs of Keidrych Rhys in uniform at the UK's National Portrait Gallery website.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

As afforded me by my time spent working a half-day on Easter Sunday, I was able to sneak out of the last couple of hours of work today, and managed to do something resembling genuine scholarship. There was a book on campus, in the library's Special Collections, which I had discovered hiding in plain sight on Professor Goethal's " Poetry & WW2" page: Poets in a War, by Kenneth A. Lohf (New York: Grolier Club, 1995). The book is a detailed catalog of an exhibition curated by Mr. Lohf, which was displayed at the Grolier Club of New York from December, 1995 through mid-February, 1996.

The Grolier Club is 'America's oldest and largest society for bibliophiles and enthusiasts in the graphic arts' (they are currently showing an autograph manuscript of Robert Burns' " Auld Lang Syne"). From the Club's webpage for Poets in a War:

In observance of the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, the Grolier Club in December 1995 presented an exhibition featuring manuscripts, first editions, drawings and portraits of 130 British poets of the 1940s who served on the battlefronts and home front.

The book is lavishly illustrated with photographs and reproductions, and I was hopeful that it might contain a picture of Reed. Alas, no such luck, though there is a reproduction of the title page of Reed's 1970 collection, Lessons of the War (New York: Chilmark Press). The text does contains detailed bibliographic information on the Lessons and A Map of Verona (London: Jonathan Cape, 1946), as well as several appraisals of Reed's poetry:

Of the poets who produced one or more memorable poems, F.T. Prince's 'Soldier's Bathing' and Henry Reed's 'Naming of Parts' (the first part of his series of poems, 'Lessons of the War'), stand out because of the ways in which they treated their specific subjects...[.] Like Prince, Reed, who after a year in the Army worked at the Foreign Office for the remainder of the war, had written only one volume of poetry, A Map of Verona (1946), by the time the war ended...[.] Though his participation in the army was brief, his series of poems 'The Lessons of War,' [sic] collected in A Map of Verona, is among the best-known group of poems of the Second World War. Like 'Soldier's Bathing,' 'Naming of Parts,' the first poem in the series, is a meditative poem in which the central conflict is between a recruit's wandering thoughts and an army officer's emotionless voice of instruction in the use of a rifle, a voice with a decided sexual dimension which is lost on the recruit who thinks solely of the beauty and sensuousness of nature. It is the human scale of these poems—both of their speakers are soldiers—that facilitates our understanding of the meaning of war to the men caught in its turmoil. (p. 26)

The library's copy appeared to be in pristine condition, or at least it had been previously handled with the greatest care. I was loathe to ask for photocopies since it would involve putting pressure on the books' virgin spine, so I settled for copying out the relevant passages in longhand, and taking pictures of everything, in case I made any mistakes (more pics on the Reeding Lessons Flickr page). An hour well spent!

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

Thus far, I have not splurged and bought a copy of the original, 1946 UK edition of Reed's A Map of Verona: Poems. (I've been getting by with a complete xerox of a library copy.) Weekends, I like do a bit of window shopping, pretending I can afford to buy a signed, first edition (images link to AbeBooks.com):

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

In this week's New Yorker, " Final Destination" ( printable article), an in-depth look at the collections and archives at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin, and the unstoppable tide of authors' papers and manuscripts which end up there:

There is not much that other institutions can do when Texas is interested. After Osborne, Stoppard, Penelope Lively, and others sold their papers to Texas, the mass departure aroused alarm in Britain—a 2005 headline in the London Times proclaimed, 'writers unite to fight flight of literary papers to u.s.' To counter the Ransom Center, Britainís national-heritage fund changed a rule prohibiting public money from being spent on material less than twenty years old; the exclusion was reduced to ten years. The change barely diminished the flow of work across the ocean, however. Staley [the Center's current director] does not have much sympathy for the aggrieved. Last year, at a conference at the British Library, Staley was asked about an essay in which the British poet laureate Andrew Motion argued that national treasures belonged in the nations that created them. He retorted, 'Like the Elgin Marbles?'

I know of at least four Reed-related items in the Ransom Center's archives: A 1944 letter from novelist Sid Chaplin to John Lehmann, calling Reed's "The End of an Impulse" in New Writing and Daylight 'the most sensible piece about modern poetry I have seen in a long time'; a 1945 typescript of one of Reed's BBC talks in the Elizabeth Bowen collection; a letter from Reed to Dame Edith Sitwell; and Sitwell's reply to Reed.

|

1528. Manning, Hugo. "Recent Verse." Books of the Day, Guardian (Manchester), 31 July 1946, 3.

Manning feels that 'Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship.'

|

Hey, Oak Knoll Books? You know why no one's bought this copy of Reed's Lessons of the War?

Because the picture you've posted is clearly of The Agamemnon of Aeschylus. Just sayin'.

|

1527. Rosenthal, M.L. "Experience and Poetry." Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review (New York), 17 October 1948, 28.

Rosenthal says Reed shares with Laurie Lee 'that unhappy vice of young intellectuals—a certain blandness of which the ever-simple irony is a symptom.'

|

Want to own an illustrated Bhagavad Gita? How about a Neo-Babylonian cylinder seal? Who wouldn't want their very own piece of Homer? Or, for the person who has everything, an 18th century shaving kit, hidden inside a faux book.

All these, and more, at a Christie's auction later this month, " The History of the Book: The Cornelius J. Hauck Collection from the Cincinnati Museum Center." From the Museum Center press release:

The breathtaking top lot of the sale is the Album Amicorum—Das Grosse Stammbuch ( large image) of Philip Hainhofer, an illuminated manuscript on vellum and paper in German, Italian, Latin and French, 1596-1633 (estimate: $600,000-800,000). This renowned 'Book of Friendship' is a monument to the princes of Europe and court art. Brought together by Philipp Hainhofer (1578-1647), an internationally influential figure who was employed by the European princes as an art advisor and political agent, the Grosse Stammbuch contains signatures and coats of arms of princely persons, paintings and drawings and an ensemble of lavishly illustrated 'natural history' pages which are strikingly meticulous, delicate and elegant.

The Hauck collection will be auctioned at Christie's, in New York, June 27th and 28th.

|

1526. Blunden, Edmund. "Poets and Poetry." Bookman, n.s., 1, no. 4 (July 1946): 14-15.

Edmund Blunden says Reed's Lessons of the War poems 'have captured something of the time-spirit and ambiguity of the recent war in a style of wit and deep feeling united.'

|

I find myself gloriously and unexpectedly free today. The library where I work has just begun an expansion project, and today is our first construction-assisted, paid vacation day. Somebody cut an utility line, and the power company had to disconnect the library from the grid to keep us from asploding, and to begin repairs. Hooray! A no-snow snowday in May! I have (almost) no idea what to do with myself.

Since the initial de-electrification happened yesterday afternoon (unelectrification? diselectrification?), I suspected this might happen, and I rose early today to prepare. Not only did I need to make frantic phonecalls to wave off my staff before they left for work ("Abort! Abort!"), but I had hopes I'd be able to visit the university's Rare Books collection (which is on main campus and still has electricity).

So, having learned my lesson with a previous visit to a library's Special Collections, I packed everything: laptop, digital camera, and pencils of varying weights and eraser-heights. Loaded for bear, I waited patiently for the doors to open, and found myself all alone, with the entire Rare Books collection at my beck (and call), and the whole staff to take care of me, just me, at nine a.m.

These last few nights after work I've been flipping through small press literary magazines from wartime Britain, searching for Henry Reed's name in Tables of Contents, with no results. (Not surprisingly.)

Kingdom Come: The Magazine of Wartime Oxford, is in Rare Books. The very nice staff brought me the collection's entire run, about seven issues from the years 1939-1943. The magazine started out very tiny, printed on fine paper in a format not much bigger than your palm, and then soon blossomed into a large magazine-sized rag, with bright, primary-colored covers: red, green, blue.

Inside, there were all the names I've grown familiar with: Spender, Read, Treece, Heppenstall. But no Henry. I resolved myself to merely requesting a photocopy of the poem "King Mark," from another journal, Orion: A Miscellany, edited by Rosamond Lehmann.

The unbound periodicals and journals in Rare Books are tied together with a sort of ribbon, soft and velvety, acid-free. This keeps all the issues together in pile. So when the staff fetched the volume I requested (1945), I actually got the pile of four volumes. After slipping bookmarks into the pages I needed in the '45, and filling out a photocopy request form, I peeked at the other three volumes.

There, in Orion 4, Autumn 1947, was a fifteen-page Henry Reed article on James Joyce: "Joyce's Progress." Lightning bolt! Thunderstruck!

The length of the article ruled out transcribing it into Notepad (as do my typing skills), but now I must wait a week to ten days for a photocopy. The semester's almost over, and there's no student help to do the grunt work. Rare Books will take digital images for you, but they won't allow you to use your own camera, drat.

And I forgot to look for an "About the Contributers" page!

|

1525. "Reed, Henry," Publishers Weekly, 152, no. 15 (11 October 1947), 1945.

A note on the publication of the American edition of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|

††

††