|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "MobyDick"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

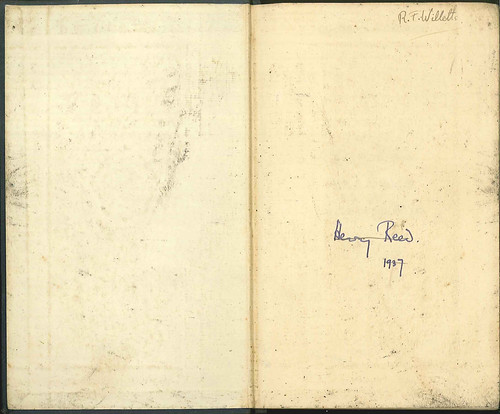

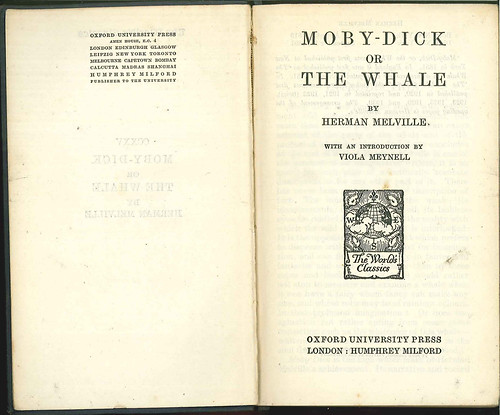

When I saw it advertised online I was by turns at first skeptical, and then conflicted: " Moby-Dick or, The Whale, by Herman Melville. London: University of Oxford Press, 1930. 676 pages plus a 16-page list of the Worlds' Classics—of which this is one; bound in dark blue cloth. Somewhat soiled on the covers and front endpapers. The free endpaper has the signatures of the poets Henry Reed (1937)—crossed out—and R.F. Willetts."

A quick search revealed that Ronald Frederick Willetts had been a Professor of Greek at the University of Birmingham. The bookseller was also in Birmingham. It would seem to be the right Reed. I felt, however, that buying this little piece of history would turn me into a Collector, capital "C". Perhaps I should leave the book in Birmingham for someone else? For a month the book languished in my online shopping cart, unpurchased, while I wrestled. In the end, avarice won the day. So here we have it, Henry Reed's personal copy of Moby-Dick:

Disappointingly, besides the two inscriptions, there is no marginalia or other marks. The silk bookmark is threaded between pages 14 and 15, in the first chapter, "Loomings":

Why did the poor poet of Tennessee, upon suddenly receiving two handfuls of silver, deliberate whether to buy him a coat, which he sadly needed, or invest his money in a pedestrian trip to Rockaway Beach? Why is almost every robust healthy boy with a robust healthy soul in him, at some time or other crazy to go to sea?

It seems unlikely—though still entirely possible—that this is the exact copy which Reed referred to when composing his radio adaptation of Moby-Dick for the BBC Third Programme (first broadcast January 26, 1947), much of which was written while Reed was living at Lovell's Farm, in Dorset. How the book came into the hands of Professor Willetts I can't say, but the two men traveled in much the same circles and it certainly seems likely that they would have known each other.

Ronald F. Willetts and Henry Reed were born a year apart—Reed in 1914 and Willetts in 1915. Both men were distinguished scholars and published poets. They attended the University of Birmingham in the 1930s, Reed going up in 1931 and Willetts in 1933; both read Classics under Professor E.R. Dodds, and studied Greek with Louis MacNeice during his tenure there. Reed took an MA in 1936 but was considered precocious; Willetts graduated in 1939. Both taught school before being called up for service during the Second World War. After the war, Reed went on to London to write for the BBC, while Willetts returned to Birmingham where he lectured in Greek until his retirement in 1981. It doesn't seem too far a stretch to believe that this book was a gift or loan.

Reed would seem to have been an admirer of Melville, in general. Besides his radio version of Moby-Dick, we also have him suggesting to Helen Gardner that Redburn may be a possible source for Eliot's "The Dry Salvages." The original working title of Reed's 1954 radio play Emily Butter was "Milly Mudd," and was envisioned as an all-female spoof of Benjamin Britten's operatic version of Billy Budd.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

Julian Potter, writing of his father's days as a radio writer and producer, in Stephen Potter at the BBC: 'Features' in War and Peace (Orford, Suffolk: Orford Books, 2004), devotes a short sub-chapter to Henry Reed's 1947 adaptation of Melville's Moby Dick for the Third Programme. The Third was all of four months old when Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel aired in two parts on the evening of Sunday, January 26th, 1947, and the play helped substantiate the new programme's reputation in providing dramatic productions for discerning listeners.

Stephen Potter (Wikipedia) produced the radio version of Moby Dick, and his correspondence and diaries lend some idea of what an arduous task such an undertaking could be: a year in the making; acquiring a composer and getting the music just so; editing Reed's script; with delays owed to casting and illness—everything down to the wire until just before broadcast.

Julian Potter falls victim to one of the classic blunders, however: he gets Reed's name wrong. Throughout the book he mistakenly confuses Henry Reed with the author Henry Green. This is simply unconscionable, and can only be forgiven if one supposes the senior Potter referring to Reed by Christian name only in his interoffice memos and diary entries.

Here is the section from Potter at the BBC concerning the production of Moby Dick, with Reed's name properly amended (pp. 195-197):

Moby Dick

Stephen's longest single production was Moby Dick, a radio adaptation of Melville's novel by Henry [Reed]. It lasted two-and-a-quarter hours and was of a length that only listeners to the Third were expected to tolerate. [Reed] had written it while working during the war as a cryptographer at Bletchley. Presumably he had a broadcast in mind, but at the time he affected to despise radio. He was converted by The Dark Tower [by Louis MacNeice]. After hearing it, he wrote to MacNeice in January 1946, 'I have always thought your claim for radio's potentialities excessive; I now begin, reluctantly, to think you may be right.' Stephen had read [Reed's] adaptation and promoted it: at a lunch with [Sir George] Barnes on 31 January it was agreed that he should produce it and that it should be earmarked for an early broadcast on the Third. 'Will [Benjamin] Britten do the music?' wrote Stephen in July. As Melville's Billy Budd was later to be the subject of a Britten opera, his treatment of Moby Dick would have been of great interest; but in the event the music was written by Anthony Hopkins.

Hopkins later described his task, saying that as soon as Stephen Potter asked him to do it, he realized that it would require a full orchestra and that since so many players crammed into the studio along with the actors would be disruptive, the music would have to be pre-recorded. He had the knack of reading aloud the text while at the same time playing his music on the piano. This helped to get the length of each stretch right, but in case of overruns, he had for the first time used two gramophones. The music that accompanied the more meditative speeches was such that if the actor overran, the music too could continue, while the music for the next scene could start with the other gramophone whenever the moment came.

For Ahab, Stephen wanted Ralph Richardson, who just at the wrong moment went down with 'flu. Stephen managed to get the already scheduled programme postponed until January. He wrote to [Laurence] Gilliam: Only by postponing can we get Ralph Richardson for Ahab. He is far and away the best actor for the part: he has the exact right combination of earthiness, ordinariness and inspired fanaticism.... If he acted Ahab, it would make this production (provided I could play my part) one of the most successful and exciting programmes that the Third Programme and indeed the BBC has ever done. Thursday and Friday, 23 and 24 January 1947. Now I start to get going with Moby, in the biggest production I have ever had to do with. Difficulty No. 1 is New Statesman and News Chronicle. I have to go to NC in the morning. In the afternoon we do the music and I like the sound. But I have to prepare tomorrow's gigantic readthrough with large cast, many of which I do not know. First horror — Ralph has 'flu (again!) and threatening laryngitis and must spend tomorrow in bed.

After many more distractions, I really get going on preparing the script (87 pages) at eleven pm and have broken the back of it at 6 o'clock in the morning. This late night made me in what I felt to be tense and therefore bad form for the read-through at Langham [Broadcasting House]. The Friday read-through, scheduled for 10.30 am to 5 pm, took place without Richardson, although he was well enough to take part in the actual production. Because of its length, it was pre-recorded in four parts over four days of the following week and broadcast in two parts on the Friday. The cast also included Bernard Miles as Starbuck. In line with the Third's new policy, a recorded repeat was broadcast on 18 February; and in September, there was a new production of the whole thing. Substitutes had to be found for Bernard Miles and two other actors, but Richardson was again Ahab: Saturday and Sunday, 6 and 7 September. Two days full rehearsal of Moby so as to leave Monday, transmission day, clear. I have been dreading this; but in fact I have enjoyed it. Ralph is in superb form. He shows us a correction of a misprint: the sentence which spoke of 'our defective police force' should of course have read 'our detective police farce'. The gorgeous thing about these rehearsals is that Ralph, the monarch, treats me as if I was Prime Minister, and sends my stock up with all the other actors in consequence. The programme was repeated a number of times thereafter. [Reed], as has been noted, became a prolific and admired contributor to radio. Nearly all his subsequent programmes were produced by Douglas Cleverdon.

Oddly enough, I was unable to find a listing for the new production of Moby Dick in the Times' BBC broadcasting schedule for the week of September 8, 1947, but there is a copy of a script with that date among Douglas Cleverdon's papers at the University of Indiana's Lilly Library. (This may be a good time to point out that the BBC taking their Programme Catalogue offline is a serious impediment to research.)

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

One of my private pleasures is reading other people's notes and marginalia in used and second-hand books (and, in some cases, library books), especially in books I'm familiar with: seeing which passages they chose to highlight, which words they underlined, questions they wrote to themselves to answer later.

Which is why Melville's Marginalia Online is so fascinating. A scholar is using digital technology to bring Melville's erased notations (.pdf) from his personal copy of Thomas Beale's 1839 The Natural History of the Sperm Whale back to light. From the February 17th Chronicle of Higher Education:

Imagine, at the end of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, that Captain Ahab and the crew of the Pequod kill the white whale instead of the other way around. That Ishmael is not alone in his escape. Steven Olsen-Smith, an associate professor of English at Boise State University, has reconstructed textual evidence that strongly suggests that Melville, whose 1851 novel stands as one of the great achievements of American literature and an enduring study of doomed monomania, entertained just such a scenario.

I was slightly disappointed to discover that the presentation is delivered as a mocked-up, generic image of Beale's book, with the notes themselves as digital recreations, a sort of marginal CGI.

It does make me wonder what Reed might have done with this new information, considering he chose to have Ishmael perish with the rest of the ship's crew for his 1947 BBC radio adaptation.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

I have eight citations to articles written by or about Reed from the Radio Times, dating from the 1950s. Since the Radio Times is more or less the British TV Guide, I suspect there are a lot more references, but these are the only ones other folks have cited. (And one or two of them are suspect!)

So I wasted twenty or thirty minutes today, browsing online bookshops that deal in collectible magazines and periodicals. Even if they all don't turn out to contain anything of interest, it still wouldn't be entirely cheap to buy the issues outright. I'd rather have groceries.

My other option is to take a field trip to the Library of Congress in D.C., which is always productive, but a bit of an adventure for a hermit like myself. It would only cost me 20¢ per photocopy, and I would be able to peruse in relative leisure.

Photocopies are so sterile, though. Nothing like the feel of an old magazine: the brittle, yellow pages smelling warmly of neglected attics and dank basements.

The small treasure I found today was on the WordAloud website. WordAloud is a repository for information on radio broadcasts. They have airdates, synopsis, and credits for all sorts of BBC radio drama, including some of Henry Reed's. Hardy's "Battle of Trafalgar"? Never heard of it. Some adaptation of The Trumpet Major? "The Sergeant's Song"?

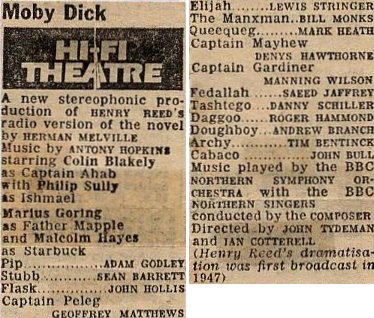

The prize among all these scraps and clues, was a clipping from a 1979 Radio Times, listing the credits for Reed's (stereophonic!) re-working of his 1947 radio adapation of Moby Dick:

Update: The London Times reveals that "The Battle of Trafalgar" was adapted for radio by Reed from Thomas Hardy's The Dynasts, which was orginally broadcast in its entirely as six ninety-minute episodes in June of 1951 (Savage, in British Radio Drama). Unfortunately, the Times was on strike at the time of the Moby Dick broadcast.

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|