|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Plays"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

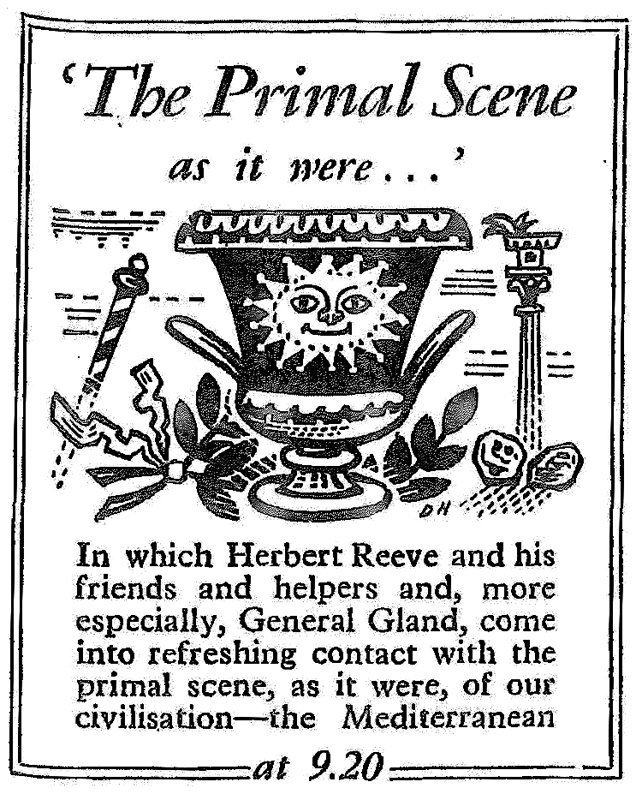

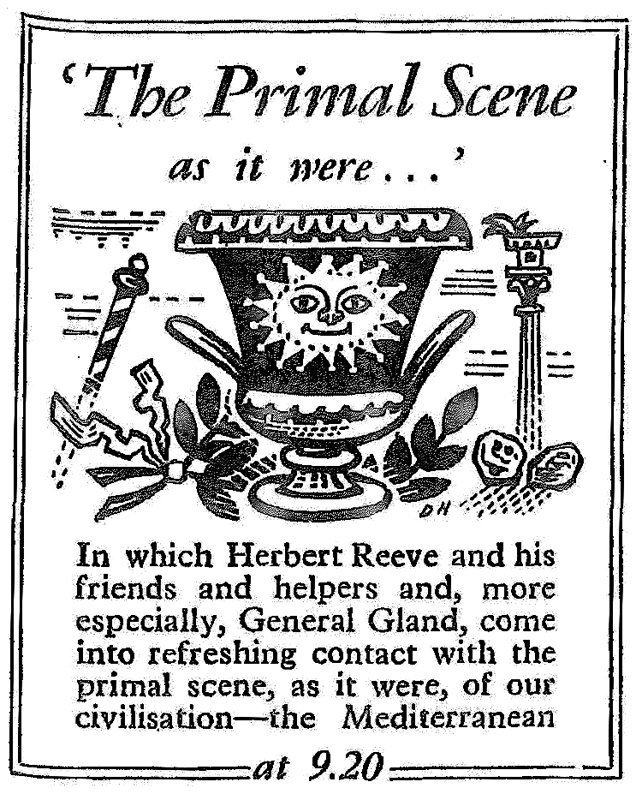

In the early months of 1958, the BBC Third Programme repeated the entirety of Henry Reed's sequence of Hilda Tablet plays—beginning with a 1953 recording of A Very Great Man Indeed—in anticipation of Reed's latest (and advertised as the last, but ultimately the penultimate) entry, The Primal Scene, As It Were.

Reed wrote a short re-introduction for the Radio Times on February 7, 1958, to give thanks and credit to the actors and musicians who brought the characters to life in his most famous and most listened-to of radio plays. He has special mention for Hugh Burden, Mary O'Farrell, the music of Donald Swann, Carleton Hobbs, and Deryck Guyler.

The Primal Scene takes place in the Mediterranean, and if I remember correctly, is the result of BBC paying for Reed's holiday to Athens and Greece, in order to research an historical play set in ancient Mycenae.

Without the Actors . . .

Beginning on Thursday with 'A Very Great Man Indeed,' the Third Programme is to revive all the Henry Reed satires. The author contributes this preface

I HAVE been told that there was once a Derby winner who was heard, in a moment of morbid self-questioning, to observe: 'Without the horse, I doubt if I could have done it.' I am not given to this kind of introspection myself and among the actors who appear in the Herbert Reeve scripts, there is none that resembles, in any respect, a horse. But I am bound to confess that the tormented jockey's remark always comes to my mind whenever people say that they have enjoyed these programmes, since, apart from the first script, A Very Great Man Indeed, they all derive directly from the performances of the actors.

I think all of us concerned with that early piece enjoyed doing it. But for some time after, I was myself so much haunted by the realistic and touching intensity with which Hugh Burden and Mary O'Farrell had enacted the scene at Hilda's piano that I found myself wistfully craving to know exactly what happened afterwards. This, and nothing else, led to The Private Life of Hilda Tablet. (The word 'composeress' has been objected to in connection with Hilda; but it seems an innocent enough counterpart to the word 'paintress.')

Hilda's music had been potently realised by Donald Swann. It was Mr. Swann's devotion to Hilda, his voluminous invention on her behalf, and a certain gleam that always appeared in his eyes whenever she was mentioned, that led to the programme about her opera, Emily Butter. It was by this time felt that more might profitably be said by Carleton Hobbs on the subject of Stephen Shewin. It was said in A Hedge, Backwards, which was billed as the last of the series, We had not however counted on Deryck Guyler's General Gland, who seemed to call for profounder acquaintance. This has led to a new programme The Primal Scene, as it Were . . . , which will be broadcast next month. I think I may safely promise that this will be the end of Herbert Reeve, The title is a quotation from the piece itself, and refers to the Mediterranean.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

A lovely little article on the current radio offerings for May, 1955, from the Literary Guide's "On the Air" column, by Philip Dalton. Discovered quite unexpectedly, using the extra morning hour afforded me by the ending of Daylight Saving Time (Summer Time, to *you* people). Among other nice things, Dalton laments that Reed's plays are consigned to the Third Programme, and not repeated on the Home Service.

Includes Henry Reed's official BBC headshot, taken circa 1950, when he was 35 years old (badly scarred in this microfilm scan):

On the Air

Covering the month's broadcasting and noting programmes to come, this radio commentary will in future be a regular feature

by PHILIP DALTON

Vastly Entertaining

Most of our poets or any reputation have written for the radio, even if few have made their' reputations on it. Louis MacNeice is better known to a wide audience than be might have been, but it is Henry Reed who has become almost completely identified with the microphone. It is almost ten years since he wrote 'Noises' and since then he has produced about seventy talks and thirty commissioned features. He has been prolific, diverse and, to my mind, almost always vastly entertaining, and he is certainly entitled to what we might call his 'benefit'—a series of revivals of some of his most popular pieces which has been running throughout April. Among these re-broadcasts were 'Return to Naples' (April 5), 'A By-Election in the Nineties' (April 11), 'The Streets of Pompeii' (April 21), and we shall hear 'Moby Dick' again on April 29. All these are Third programme offerings, although for Reed's sake I would like to have seen some of them broadcast on the Home Service: they could baffle no one. The Literary Guide has an interesting history, starting out in 1885 as Watt's Literary Guide (sort of propaganda for free-thinkers and the science-minded), and changing to the Humanist in 1956. Still published by the Rationalist Association as the New Humanist.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

One of my favorite pieces on Henry Reed is this 1971 retrospective from the Guardian, " The Reeve's Tale," by the music critic Christopher Ford. It was a promotional piece written for the publication of Reed's two collections of radio plays, The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio, and Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (London: British Broadcasting Corporation). From this article we also get not one ( Manchester edition), but two photographs of Reed, ( London edition, shown here) taken by Peter Johns ( previously).

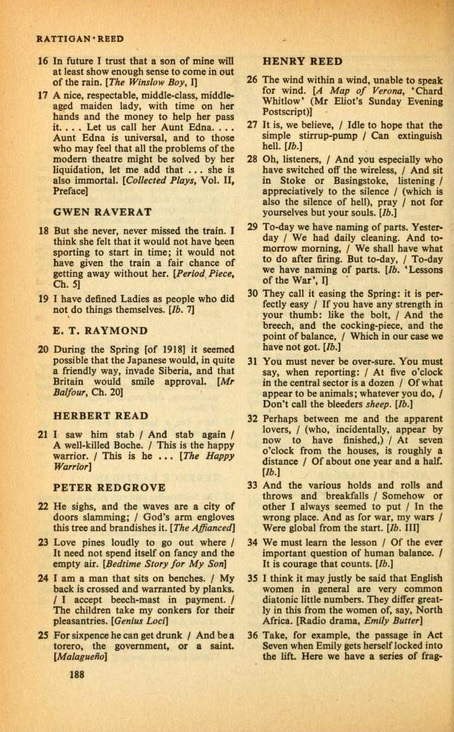

In the article's closing paragraph, Reed says, "I saw the Penguin Dictionary of Modern Quotations in a shop. I remember thinking 'I've got 150 sleeping tablets at home, and if I'm not in that I'll take some of them with a large Pepsi-Cola'."

Ford reports that Reed's quotes take up "more than three columns, the entries mostly coming from the Tablet plays."

It's difficult to express what an achievement this amount of textblock is, appearing in this small Penguin paperback: Reed gets more than a page and a half of space devoted to his poems and plays. He actually appears on the same page with the poet and critic he is famously often confused with, Herbert Read. Read gets only one quote (and surprise! It's not " To a Conscript of 1940"):

Looking to Reed's peers, we find that even W.H. Auden receives only two columns; T.S. Eliot gets two and a half; Louis MacNeice gets one column: half a page. Stephen Spender, barely half a column. Stevie Smith gets five quotes. C. Day Lewis? Four. George Orwell gets three, three and a half columns? A little more. W. Somerset Maugham gets three columns. I mean, Evelyn Waugh rates three columns. This is what I'm saying.

I think the superabundance of Henry Reed in this curious volume is owed to two things: firstly, the entire Hilda Tablet sequence was replayed on the new BBC Radio 3 between December, 1968 and January 1970. ("Altogether, they totalled seven. The number is sometimes given as nine; but people exaggerate.") These repeats were in tribute to the incomparable radio actress Mary O'Farrell, who had died on February 10, 1968. Reed hosted (and Douglas Cleverdon produced) a program of recollections and recordings for O'Farrell in January, 1969. Dame Hilda died with O'Farrell, and a planned eighth installment for the radio was abandoned.

Secondly, this largess must be credited (or blamed) on the editors, J.M. Cohen and his son, M.J. Cohen. I suspect the elder Cohen knew Reed's work not just from the radio, but from earlier anthologies for Penguin: The Penguin Book of Comic and Curious Verse (1952), More Comic and Curious Verse (1956), and Yet More Comic and Curious Verse (1959).

I'll use the Cohens' book to expand my rather meager " Henry Reed quotes" page.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

From the Radio Times for February 27, 1969, a blurb from Henry Reed's long-time producer, Douglas Cleverdon, regarding the rebroadcast of Reed's Hilda Tablet cycle after the death of actress Mary O'Farrell:

The Private Life of Hilda Tablet

The broadcast repeat of A Very Great Man Indeed on Christmas Eve, followed by last month's radio tribute to Mary O'Farrell, aroused once again the unbridled enthusiasm of the Hilda Tablet fans. They will be gratified to learn that, after The Private Life this week, the remaining five programmes of the saga will be repeated at quarterly intervals.

Henry Reed has recalled how an unexpected letter from Mary O'Farrell prompted him, for his own amusement, into an elongation of the scene of Herbert Reeve's first confrontation with the composeress in A Very Great Man Indeed.

The force of Hilda's personality compelled him to devote an entire programme to her decision that Reeve should abandon his work on the life of Richard Shewin and concentrate all his energies on a biography of herself, for which (she thought) twelve volumes would suffice—it was enough for Gibbon, it was enough for Proust. In this Reeve would have the cardinal advantage of her own continual advice and co-operation. Douglas Cleverdon

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

This week marks the 70th anniversary of the BBC's Third Programme, which broadcast from September 29, 1946 until April, 1970, when it was replaced by BBC Radio 3. Too short a season.

Radio 3 is running 70 days of celebrations to mark the anniversary, including " Three Score and Ten," 50 episodes of poets reading from their work and others, a play(!) dramatizing the start of the Programme, " The Present Experiment," as well as rebroadcasts of Humphrey Carpenter's 1996 history, " The Envy of the World." Henry Reed's Hilda Tablet plays are mentioned in episode two of Carpenter's documentary, " Rudely Truncated."

Andy Walmsley is doing a much better job of covering the anniversary over at Random Radio Jottings. For my part, I thought I would bring out this summation of Henry Reed's early contributions to the Third Programme by Douglas Cleverdon, published in the Radio Times on April 1, 1955: "A Henry Reed Season," billing a series of repeat Reed programmes from the first half of the 1950s:

A Henry Reed Season

Any young author who aspires to write for radio cannot do better than study the various programmes Henry Reed has written.'

DOUGLAS CLEVERDON, who has produced many of them, introduces the series of revivals beginning in the Third Programme this week

MILLIONS of regular fans look forward to Take It From Here, The Archers, The Goon Show; a very much smaller number of listeners tune in with an even more fervent devotion to any programme written by Henry Reed. For Henry Reed is that rarest of birds, the creative writer who finds in radio his most fruitful medium of expression.

His reputation as a poet was founded on a single volume published nearly ten years ago—A Map of Verona. His only other book is his broadcast version of Moby Dick. His contributions to radio, however, consist of about thirty scripts and seventy talks. Such talks as Towards 'The Cocktail Party' have revealed his critical insight: and the incisive comments he was accustomed to make as a member of 'The Critics' proved his fearlessness in judgment.

But it is principally through the scripts written for the BBC Features Department that he has secured his increasingly appreciative audience. His first work, broadcast from the Midland studios, was a jeu d'esprit on Noises. Then, in January 1947, came his first major work for broadcasting, a radio play based on Herman Melville's Moby Dick, with linking narration in verse a recording of the second production (with Sir Ralph Richardson as Captain Ahab) will be broadcast on April 29. Pytheas (May 1947) was followed in 1949 by The Unblest and The Monument, two dramatic studies in verse of the Italian poet Leopardi, a recording of the 1950 production of The Unblest will be broadcast on April 15.

The Inspiration of Italy

The love of Italy seems to be a permanent element in the English literary tradition; and in Return to Naples (to be re-broadcast on April 5), Henry Reed nostalgically recalled a series of visits to a family in Naples before and after the war. For this autobiographical piece he evolved a simple but elegant variation of the usual radio narration, causing the narrator to address not the listener, but the author himself. A By-Election in the 'Nineties (1951: to be repeated on April 11) was a purely comic documentary, based on contemporary newspaper reports of a Dorset by-election.

Then followed two more programmes on Italian themes: The Streets of Pompeii, which was awarded the Radio Italiana prize for 1953 (a new production will be broadcast on April 22); and The Great Desire I Had, based upon the fancy that towards the end of the sixteenth century Shakespeare visited Italy and fell in with the players of the Commedia dell' Arte.

Then followed the group of satirical comedies, A Very Great Man Indeed, The Private Life of Hilda Tablet, and Emily Butter, with their highly sophisticated wit and exuberant characterisations. As all three have been broadcast fairly recently, none will be repeated during the coming weeks; but many listeners hope that they will form part of the Third Programme's regular repertoire. Henry Reed's latest work, Vincenzo, was broadcast last week as a precursor to the present series of repeats. I wish I knew where that quote from Douglas Cleverdon used as the epigraph comes from.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

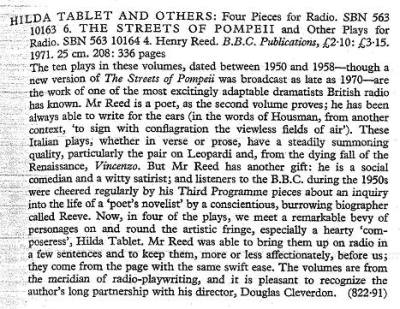

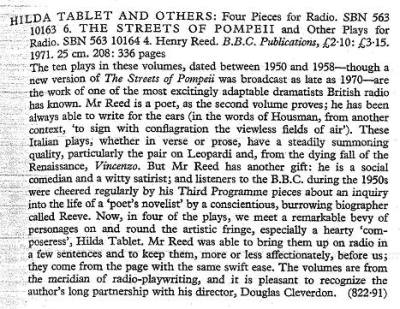

In the Spring, 1972 issue of the journal of the Society of Teachers of Speech and Drama there appears an argument for the release of recordings of Henry Reed's radio plays. Jane Gregg reviews two collections of Reed's plays produced for the BBC Third Programme, published in 1971 by BBC Publications: Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio, and The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio.

Gregg calls the Hilda Tablet plays "the funniest and most sustained piece of social comedy written for radio," and expresses concern over the ephemeral medium of "aural" art such as radio, arguing that Reed's plays should get the same treatment as Dylan Thomas' Under Milk Wood, and be released as recordings.

Hilda Tablet and Others — four pieces for radio

by HENRY REED. BBC: £2.10.

The Streets of Pompeii and other plays for Radio

by HENRY REED. BBC: £3.15.

All Third Programme listeners please note that the plays of Henry Reed you so enjoyed between 1949 and 1958 are now in print—a permanent memorial of the radio drama which otherwise has no permanent life.

As Reed says in a most interesting foreword to The Streets of Pompeii, 'They were not for the most part written with any idea that they might appear in print. When it was suggested that they should, I was naturally delighted: it seemed to imply that they had not entirely gone in one ear and out of the other'.

I have just taken up knitting and when reading the pattern I have tried to visualise the finished article. Possibly knit two together through back loops creates a picture for the experienced knitter but even so it remains for most of us simply a code. In the same way the printed word is a poor substitute for radio drama. 'Cross-fade rapidly' needs a great deal of aural imagination.

Hilda Tablet and Others consists of four pieces from what many regard as the funniest and most sustained piece of social comedy written for radio. They are A Very Great Man Indeed, The Private Life of Hilda Tablet, A Hedge, Backwards, and The Primal Scene, as it were. The productions were all by Douglas Cleverdon, with music by Donald Swann and the casts include most of the great BBC repertory names: Hugh Burden, Carleton Hobbs, Gwen Cherrell, Mary O'Farrell, Marjorie Westbury . . . (dear Marjorie Westbury as Steve in Paul Temple — there's nostalgia for you) . . . the list is endless and very well-loved. The plays arise out of the research by Reed's alter-ego Reeve into the life of Richard Shewin, novelist.

The Streets of Pompeii on the other hand contains those plays which have Italian themes and settings. They are Leopardi in two parts: The Unblest and The Monument; The Streets of Pompeii, Return to Naples, The Great Desire I Had, and Vincenzo. Again the productions were by Douglas Cleverdon with a cast which sounds like Who's Who in Radio.

The BBC are of course quite right and to be commended for publishing Henry Reed's radio plays but now, before they disappear aurally altogether, may we have them recorded? After listening to the record of Under Milk Wood recorded by Argo with the cooperation of the BBC, I am convinced that there is a market for radio plays on record.

JANE GREGG. I note with some dismay that a quick search of the British Library Sound & Moving Image Catalogue reveals no recordings of A By-Election in the 'Nineties (1951), The Great Desire I Had (1952), A Hedge, Backwards (1956), The Primal Scene, As It Were (1958), or Musique Discrète (1959). Perhaps, however, the current Save Our Sounds project might turn a few up.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

This review of the premiere of Reed's second installment in the Hilda Tablet series, The Private Life of Hilda Tablet, appeared 59 years ago today, in The Listener for June 3, 1954. The reviewer was J.C. Trewin (later OBE), drama critic for The Observer for more than sixty years.

I began by typing a few excerpts of Trewin's (and Reed's) best bits. The "best bits" turned out to be the article entire.

Sound Broadcasting DRAMAAlive and Dead

And now we must have the private life of Stephen Shewin. I can hardly wait for it. Henry Reed, who has discovered these curious people—clearly they have been hovering, in a lather of excitement, to come to the microphone—has just reached the story of Hilda Tablet. A very fine story it is. When it appears in print, if poor Herbert Reeve is still alive, it will run into twelve volumes—though that, as Reeve murmured in the plaintive, melancholy-desperate tones of Hugh Burden, must be years and years ahead. Years and years.

You must forgive me. I may be talking to myself, and you may not have met these people. I hope you have. It is eight months since Henry Reed, in the Third, has had his joke at the expense of the conscientious, burrowing biographer. The resolute Reeve looked for the facts beneath the work of the 'poets' novelist', Richard Shewin, and, in the course of his researches, he met the most extraordinary bevy of personages on and around the comic literary fringe. At the time I liked the 'composeress' Hilda Tablet. Now Herbert, even fainter than before, but still pursuing, has saddled himself with another assignment.

The title, 'The Private Life of Hilda Tablet' (Third Programme), says just what has happened. In seeking Shewin, poor Reeve has found Hilda coiling herself furrily about his neck. He is hers forever, and it is going to be a ticklish journey. As someone observes, it needs tact to write the biography of a living subject. And Hilda is living. Undeniably. Her all-woman opera, 'Emily Butter', 'embraces the whole of music'; she has written a quintet for eight instruments ('a lot of instruments for a quintet, I freely grant you'); and she seems to have a passion for adding to her works: at least, to works about her. The idea is simple when it begins: 'A couple of fellows called Faber and Faber are after my life—only 350 pages by this autumn'. But, a few months on, she has resolved, and Herbert has agreed—could he have done otherwise?—that the biography shall be in twelve volumes. It has to have Epic Scope (no doubt Cinemascope as well, if things go much further).

Once more, Mr. Reed has written with the sharpest, wittiest point. Some of his people are old friends; I plead—see first sentence—for a third installment on Stephen Shewin, who still lives, with his wife, in the cat-filled house, shooting his phrases (thanks to Carleton Hobbs) like poison-tipped arrows. But there are new pleasures also. We meet the librettist, who finds Hilda a trifle vexing. Has she not changed the original story of 'Emily Butter', set in the sixteenth century on a boat anchored off Rimini, to something about the bargain basement of a department store? Then there is the Vicar of Mull Extrinseca ('We rub along, you know'), who is delighted that Hilda's embalmed feet are to preserved in the church—in due course. There is the Duchess who begins every sentence with 'One wonders', and who can wonder with surprising effect. There is the Viennese singer who has not yet said 'Goodnight Vienna', though all her attempts are thwarted.

And there is always, and massively, our old acquaintance Hilda herself (Mary O'Farrell), to explain that 'Music fell for me; I was flirting with architecture at the time', or else that she is neither the marrying sort of girl nor a girl who easily offended. 'Please don't mind my saying it', she begins briskly, and at once a storm-cone is hoisted. Mr. Burden is a dolorous joy: then, most of this effort is a joy, though I think Hilda's speech to her old school goes on too long at the end. We know her reasonably well by then, and some of her effects are expected.

Still, the 'Life', which was produced by Douglas Cleverdon, is a cheerful find for what Mr. Reeve-Burden calls 'the ever-admirable Third Programme'. Now let us have a few more poisoned arrows from Stephen Shewin. And his wife, I am sure, can be helpfully elaborated.

[pp. 983-984]

The Private Life of Hilda Tablet was followed by Emily Butter (1954), A Hedge, Backwards (1956), The Primal Scene, As It Were (1958), Not a Drum Was Heard (1959), and Musique Discrète (1959). The plays were collected (not including Emily Butter) in Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (British Broadcasting Corporation, 1971). Because of the poor quality of my Listener scan, I have illustrated this post with a picture from the Radio Times for Musique Discrète.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

In the 1950s, Joan Newton was the radio and television reviewer for the Catholic Herald. Through the magic of the paper's online archive, it's possible to trace Ms. Newton's love affair with Henry Reed's Hilda Tablet plays on the BBC's Third Programme, starting with A Very Great Man Indeed in 1953:

Somebody's guardian angel—mine, I suppose—suggested to me to listen to Henry Reed's "A Very Great Man Indeed," produced by Douglas Cleverdon on the Third. Just before, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra from Edinburgh had been coming through very badly and I was prepared to have to turn off the play as well. I'm glad I didn't.

It was about "the late Richard Shewin, 'the poets' novelist,'" and his biographer, Herbert Reeve (Hugh Burden), was visiting the great man's relations and friends to get an idea of his character.

"Dear me, I've never heard of Richard Shewin," I was thinking as I listened to the beginning. But when the earnest biographer got upstairs to see the permanently bedded brother of the late R.S., and after meeting with the sister-in-law and her cats, I realised that either it was meant to be funny or something had gone wrong somewhere. And funnier and funnier it grew, and more and more enjoyable.

I find it hard to decide which incident I enjoyed most—Mary O'Farrell as the composeress, Norman Shelley being a contemporary novelist, Harry Hutchinson as the Irish poet, or the glorious ending with the late novelist's nephews singing "Don't Hurt My Heart," a very tearful lyric in the Frankie Laine manner. Repeat, please.

This loss in a few days of almost all the family's chief stand-bys for lighter listening [ Take it from Here, Life with the Lyons, Talk about Jones, and Have a Go] was made bearable only by the further repeat of the Third Programme's "A Very Great Man Indeed," written by Henry Reed and produced by Douglas Cleverdon. I had heard this twice before, but laughed as much as ever.

The only jarring note for me was the Graham Greeneish episode about the worried priest at the end, which was an accurate pardoy in style only and not in content, and had too much the air of mischievous afterthought to make an artistic conclusion.

I wonder if the author and producer—and perhaps more especially, the composer, Donald Swann—will be able to repeat their success in " The Private Life of Hilda Tablet," promised us for May 24 and 26. Those who did not hear "A Very Great Man" may like to know that Hilda is a modern composer. They ought to be warned, too, that the play is unlikely to be wholly suitable for children. Perhaps it was rather much to expect that Henry Reed should hit the bell so definitely with his "Private Life of Hilda Tablet" (Third Programme) as he did with "A Very Great Man Indeed." All the same, it was a splendid entertainment and one still clamours for more of the same kind.

The defects in this second show—they are defects in comparison only—seemed to me to be that the characters had become more familiarly "types" than they were before, that the satire was slightly less sharp, and that some episodes, such as the "drunk" scene at Hilda's school, were rather too drawn out.

Mary O'Farrell as Hilda, the modern composeress, was as hearty and vigorous as ever but not quite as real as before—less Waugh and more Wodehouse. Herbert Reeve, the scholar through whose reminiscences we become acquainted with all these odd people, was still a deliciously wide-eyed and dedicated Boswell; but in the earlier show his approach was more "dead-pan," more Third Programme, and consequently he came out more amusingly in contrast with the astonishing goings-on in which he gets himself involved.

I hope we shall have more of one gorgeous new character, Deryck Guyler as the Rector of Mull Extrinseca.

Donald Swann's clever musical parodies, which naturally had more scope this time, lived up to all expectations. And that brings me on to the unhappy case of Marjorie Westbury, who was so impressive as Elsa Strauss, Hilda's long-suffering singer—'Throw yourself at the note if you like, but for heaven's sake don't hit it!'—that I am now quite unable to think of her as anything else.

This week they [ Said the Cat to the Dog] were assisted by "Mrs. Kerry," a cow, but she is, perhaps, a bit too much of a chatterbox and just a weeny bit too "Oirish" for our liking. I mention her specially because she is played by another of those versatile radio actresses, Mary O'Farrell. It's a far cry from her acting a cow to being the energetic Hilda Tablet in the latest of Henry Reed's witty Third Programme diversions, " Emily Butter."

I was looking forward to hearing Hilda's much-publicised opera. Unfortunately, a slight indisposition prevented me, and I only hope that there will soon be a repeat. In all my years of radio listening I have yet to find purer gold than in the Third Programme's set of plays by Henry Reed about the mythical author Richard Shewin. A few weeks ago we had a repeat of the first play, "A Very Great Man Indeed." I do not usually like hearing a play twice, but this I have heard four or five times and have experienced the same delight each time.

At the end of February, " A Hedge Backwards," which is meant to be a final digression on the subject, gave us nearly as much pleasure. Hugh Burden, as the innocent and revering biographer, is perfect and as sordid fact after sordid fact about the "great" author is brought to light our enjoyment increases with his bewilderment. The musical satires by Donald Swann are also perfect and if you have never listened to these plays you must certainly look out for any repeats. Last Friday, too, on the Third, I heard again the third of the wonderful trilogy about the works of the fabulous Richard Shewin and Hilda Tablet—this being "A Hedge Backwards." I hope these three plays will be offered to us again and again for many years to come.

The only fault I found with this collection [ From the Third Programme: A Ten Years' Anthology] was that it had not included some of the lyrics, at least, from Henry Reed's masterpieces, "A Very Great Man Indeed" and "Through a Hedge Backwards" [ sic]. This is a strictly personal grouse because the editor has included Reed's more serious "Antigone" in this anthology. Thursday was, in fact, a happy day on the radio for everyone, for in the evening we heard again the first of Henry Reed's saga about literary people "A Very Great Man Indeed." I have praised this work and its sequels so often that I am afraid of being accused of some queer kind of fixation.

My favorite bit: '[U]nlikely to be wholly suitable for children.'

Hilda Tablet is 60 years old this year, and 2014 will be the centenary of Henry Reed's birth. Repeat, please.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

In 1971, the BBC issued two collections of Henry Reed's plays for radio: Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio, and The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio. The Hilda Tablet volume collects the plays A Very Great Man Indeed (1953); The Private Life of Hilda Tablet (1954); A Hedge, Backwards (1956); and The Primal Scene, As It Were (1958), including restoration of some "indelicate" scenes which had been censored or changed for broadcast.

To mark the publication of the plays, Reed was interviewed by Christopher Ford for an article in the Guardian, " The Reeve's Tale" (Herbert Reeve was the bumbling biographer in the Tablet plays, you see). A retrospective of the plays and their broadcasts, the article features this wonderful photograph of Reed (poorly scanned, sadly), taken by staff photographer Peter Johns:

Reed's quotes for the article amount to just a few paragraphs. Prodded about rumored accusations of libel from (the unnamed) composer Elisabeth Lutyens for his Hilda Tablet character (voiced by Mary O'Farrell), Reed deflects:

As long as the characters are funny it doesn't matter who you're getting at.... In fact I'm not 'getting at' anyone, only myself—there's a good deal of aboriginal Hilda Tablet in me.

The big revelation in the article is that Reed was actually working on an eighth Hilda Tablet script as late as 1968 (in his dedication for Hilda Tablet and Others, Reed says "Altogether, they totalled seven. The number is sometimes given as nine; but people exaggerate"):

I was writing another, it was going to be called 'After a Certain Age'—I was writing it one night and the next morning Douglas Cleverdon, the producer, came round for some other reason and had to break the news that Mary O'Farrell was dead. She was a sine qua non. So it was never completed, but Hilda was going to be the reason why Skalkottas had suppressed his music all his life. We were going to be make out that this was on Hilda's advice.

Mary O'Farrell died on February 10, 1968, more than eight years after the last play in the Hilda Tablet saga, Musique Discrète.

The article closes with a hilarious anecdote of Reed still having trouble coming to terms with his place in the canon of literature and broadcasting, even at the age of 57:

I saw the Penguin Dictionary of Modern Quotations in a shop. I remember thinking 'I've got 150 sleeping tablets at home, and if I'm not in that I'll take some of them with a large Pepsi-Cola.'

Ford reports more than three columns were devoted to Reed in the 1971 edition.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

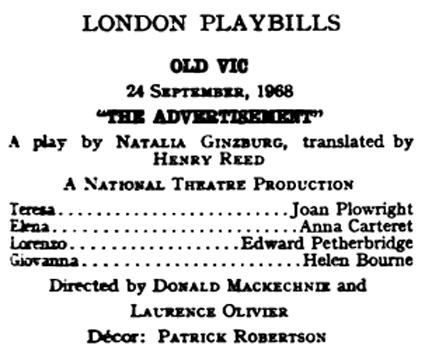

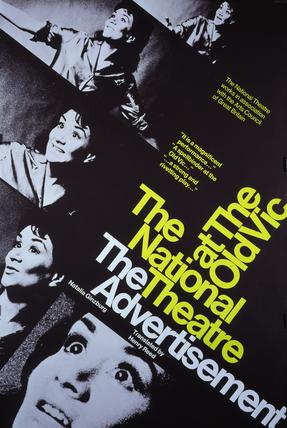

Playbill facsimile for the 1968 National Theatre production of Ginzburg's The Advertisement, translated from the Italian by Henry Reed, directed by Donald MacKechnie and Laurence Olivier. From Who's Who in the Theatre (1972), in the HathiTrust digital library.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

Happy Labor Day, comrades! I am enjoying a much-needed day off, despite the university being in full session, as classes began only last week. I worked twelve days in a row (plus a Pleasant Valley Sunday), and today I get to celebrate the fruits of that labor. I've been trying to get caught up on items which I copied or collected over the summer: tidbits, hors d'oeuvres, and appetizers, mostly; mentions, blurbs, and anthologies.

Two items come from the serial British Book News, a monthly collection of reviews of new books, put out by the British Council between 1941 and 1993 as a purchasing guide for schools and libraries.

The earliest entry for Henry Reed appears to be from July, 1946 (.pdf); a recommendation for Reed's poetry collection, A Map of Verona:

a map of verona. Henry Reed. Cape, 3s. 6d. lC8. 60 pages.

The first book of a distinguished poet and critic. Stylistically, Mr. Reed is considerably influenced by the later manner of T.S. Eliot. In the title poem he muses over a map and its literary and historical associations; in 'Tintagel' he evokes memories of Tristram and Iseult in the ruins of the castle; the more Tennysonian 'Philoctetes' and 'Chrysothemis' take the reader back to the ancient Greek world. There is also an ironical section, 'Lessons of the War'. (p. 276-277)

Later (much later), in the British Book News for February, 1972 (.pdf), we find an announcement for the publication of Reed's twin collections of BBC radio plays, Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio, and The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971):

(p. 153)

The Housman quote, while a lovely sentiment and excellent metaphor for radio, is gotten slightly wrong. It should be 'They sign with conflagration / The empty moors of air' (Google Book Search). (I'm not sure where "viewless fields of air" is lifted from. The earliest I can find is in The Memoirs of Carwin the Biloquist, serialized by Charles Brockden Brown between 1803 and 1805.)

Reed also appears in British Book News for his pamphlet of criticism written for the British Council, The Novel Since 1939 (1946).

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

Henry Reed was an inveterate Italophile, who probably spent more time thinking about being in Italy than he actually spent there, visiting. Take for example his 1942 poem, " A Map of Verona," in which he pores over a map of the city, yearning to return. Reed had studied Latin in grammar school , winning the Temperley Latin prize and a scholarship to the University of Birmingham. His Latin must have led him directly to the Italian poet, Leopardi, whose life he would later dramatize in two radio plays: The Unblest (1949), and The Monument (1950). By the outbreak of World War II, Reed's Italian was fluent enough to earn him a post as a translator at Bletchley Park.

Exactly how many times Reed visited Italy during his lifetime seems to need a bit more research. The two sources we have for this are Stallworthy's Introduction to the Collected Poems, and James S. Begg's thesis, "The Poetic Character of Henry Reed."

Stallworthy implies that Reed's father (Henry, Sr.) financed his son's first excursion to Naples in 1936, after Reed graduated as the University of Birmingham's youngest MA, and entered the workforce: 'Like many other writers of the Thirties, he tried teaching—at his old school—and, again like most of them, hated it and left to make his way as a freelance writer and critic. He began the research for a full-scale life of Thomas Hardy, and his father financed a first trip to Italy.' Beggs, however, states that Reed's first trip was in 1934, after his BA, and that the 1936 visit was his second, returning again in 1939.

Regardless of how many times Reed actually visited Italy, there is the question of how he got there. How, exactly, did an Englishman on holiday in the mid-1930s travel to Italy? It seems unlikely that he would have taken advantage of the new world of passenger air travel, though it is possible. Much more likely, however, is that he traveled by rail or boat, or both.

Professor Adele Haft has suggested in her article "Henry Reed's Poetic Map of Verona: (Di)versifying the Teachings of Geography IV" ( Cartographic Perspectives 40 (Fall 2001): 32-50) that Reed's much-studied map of Verona (.jpg) was most likely from a popular guidebook at the time; possibly the 1928 or 1932 editions of Baedeker's Italy: From the Alps to Naples, or the Blue Guide Northern Italy: From the Alps to Rome (1924). Let's consider Baedeker's suggestions (.pdf) for travel:

C. Routes from England to Italy.

By Railway. The following are the chief routes from London to Milan (through-carriages from the Continental port, unless otherwise stated). Fares are subject to frequent alterations. — Travellers are strongly recommended to insure their luggage (at any of the tourist agencies or on application at the railway booking-office).

(1) Viâ Calais, Laon, and Berne, 794 M., by the Anglo-Swiss-Lötschberg-Italian Express daily in 23 hrs. Fares 7 l. 10 s. 1 d., 5 l. 4 s. 9 d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 13 l. 4 s. 9 d., 9 l. 9 s. 1 d..

(2) Viâ Calais, Laon, Bâle, Lucerne, and the St. Gothard Tunnel, 842½ M., by the Anglo-Swiss-Gothard-Italian Express daily in 22¾ hrs. Fares as above.

(3) Viâ Calais, Paris, and Lausanne, 806½ M., by the Simplon-Orient Express (train de luxe, supplementary fare payable) daily in 25 hrs. (7 l. 6 s. 11 d.) and the Direct Orient Express in 27 hrs. (fares as above).

(4) Viâ Bologne, Paris, the Mont Cenis Tunnel, and Turin (change), 874 M., by the Rome Express (train de luxe) daily in 27 hrs. (supplementary fare payable). Ordinary fares 7 l. 12 s. 6 d., 5 l. 5 s. 6 d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 13 l. 7 s. 5 d., 9 l. 10 s. 6 d..

(5) Viâ Ostend, Brussels, Strasbourg, Bâle, and Lucerne, 845½ M., daily in 28¾ hrs. Fares 6 l. 18 s. 2 d., 4 l. 15 s. 4 d.

(6) Viâ Dunkirk, Lille, Strasbourg, Bâle (change), and Lucerne, 848 M., daily in 31 hrs. Fares 6 l. 8 s. 6 d., 4 l. 4 s. 8 d., 3 l. 2 s. 1 d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 10 l. 17 s. 3 d., 7 l. 6 s. 0 d., 5 l. 8 s. 4 d.

By Air. The journey from London to Italy may be accomplished by the aeroplanes of the French Air Union as far as Marseilles (viâ Paris and Lyons; daily, except Sun., in 11 hrs., including motor-car journeys; fare 12 l. 15 s.). There is also a service from Paris to Bâle, Zürich, and Lausanne. Comp. p. xvii.

By Sea. Regular sailings are made by the liners of the under-mentioned companies. The fares average 17-25 l. and the voyage lasts about 8 days. Special tourist fares are offered during the summer, particulars of which may be had on application to the companies (London addresses given below) or to any travel agency (C.I.T., p. xvi; Thos. Cook & Son, Berkeley St., Piccadilly, etc.; American Express Co., 6 Haymarket, S.W. 1; etc.).

Orient Line (5 Fenchurch Avenue, E.C. 3) from London to Naples. — Nederland Royal Mail Line (60 Haymarket, S.W. 1) from Southampton to Genoa. — Ellerman's City and Hall Lines (104-106 Leadenhall St., E.C. 3) from Liverpool to Naples. — Nippon Yusen Kaisha (25 Cockspur St., S.W. 1) from London to Naples. — German Africa Service (Greener House, Haymarket, S.W. 1) from Southampton to Genoa.

Looking to Reed's radio plays for some clue, we find a mention of trains to Rome and Naples in the opening of Return to Naples (1950):

Narrator: But that was not yet in Naples, you remember; that was in Rome. That morning, as the train moved South into the early sunlight of the campagna, you had drifted into conversation with an elderly doctor. He invited you to breakfast when you got to Rome. You went. You met his wife. You ate. You drank. And you were told you might stay in their apartment instead of going to a hotel. You accepted. Then you were left to doze off the effects of the journey in the misty heat of the shuttered salone. You slept. You woke. And you saw Alberto for the first time: fat, white-clad, tiptoeing gingerly across the room on his eternal blisters . . . Later that day, he wrote a letter which you were directed to give to his mother in Naples. It began, Carissima Mamma . . .

Alberto: 'Dearest Mamma, This young man, who will present my letter to you, is a very great friend of mine, whom I met this afternoon at the house of Doctor Cappocci . . .'

Narrator: That afternoon you had walked together to the Porta Pia, his small fat hand had created a pool of sweat in the crook of your arm . . .

Alberto: '. . . His name is Enrico. He is English, and is staying with Doctor Cappocci, and next week he is going to Capri. On the way, he will call on you in Naples. Please receive him into our home with the greatest kindness. Your most affectionate Alberto.'

Narrator: That letter, which was never delivered, you kept for many years, together with Alberto's other gifts: the sprig of unpolished coral, the slab of marble pavement from Tarquinia, and the life of Admiral Gravina, which sixteen years later you have yet to read . . .

There was no need to deliver the letter of introduction, for in the end Alberto's father and brother came up to Rome to fetch you, and you all travelled to Naples together.

(faint continental train noises in background)

So, putting two and two together, as it were—if we rely on Reed's autobiographical inspiration for his play—we can place him on the Milan-Naples train through Italy, via Switzerland and France, headed south to Rome, on his way to Naples and the island of Capri. And Reed specifically mentions that his titular "return" to Naples took place two years later, following the Italian conquest of Abyssinia (Ethiopia), so the 1934 and 1936 dates would seem correct. The play places Reed's third visit in 1939, a year before Italy declared war on France and Great Britain. All in all, the "H." in the play visits his adopted Neapolitan family a total of five times, over the course of two decades.

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

Working from the (somewhat incestuous) bibliographies in British Radio Drama, Contemporary Authors, Contemporary Poets, and The Dictionary of National Biography, here's a nearly complete list of Henry Reed's writing for radio, including his translations from French and Italian (but not his talks or criticism): - Noises (4 March 1946)

- Noises—Nasty and Nice (1947)

- Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (26 January 1947)

- Pytheas: A Dramatic Speculation (25 May 1947)

- The Unblest: A Study of the Italian Poet Giacomo Leopardi as a Child and in Early Manhood (9 May 1949)

- The Monument: A Study of the Last Years of the Italian Poet Giacomo Leopardi (7 March 1950)

- Return to Naples (17 August 1950)

- Canterbury Cathedral: An Exploration in Sound (with Elisabeth Lutyens, 7 November 1950)

- A By-Election in the Nineties (3 March 1951)

- The Dynasts (adapted from Thomas Hardy, 3-9 June 1951)

- Malatesta (translation, Henry de Montherlant, 26 February 1952)

- The Streets of Pompeii (16 March 1952)

- The Great Desire I Had: Shakespeare and Italy (26 October 1952)

- Westminster Abbey (with Elisabeth Lutyens, 1953)

- A Very Great Man Indeed (7 September 1953)

- All for the Best (translation, Luigi Pirandello, 22 November 1953)

- The Private Life of Hilda Tablet: A Parenthesis for Radio (24 May 1954)

- Hamlet; or, The Consequences of Filial Piety (translation, Jules Laforgue, June 20 1954)

- The Battle of the Masks (translation, Virginio Puecher, 6 September 1954)

- The Queen and the Rebels (translation, Ugo Betti, 17 October 1954)

- Emily Butter: An Occasion Recalled (14 November 1954)

- The Burnt Flower-Bed (translation, Ugo Betti, 23 January 1955)

- Vincenzo: A Tragicomedy (29 March 1955)

- Holiday Land (translation, Ugo Betti, 5 June 1955)

- A Hedge, Backwards (29 February 1956)

- Crime on Goat Island (translation, Ugo Betti, 7 October 1956)

- Don Juan in Love (translation, Samy Fayad, 5 November 1956)

- Alarica (translation, Jaques Audiberti, 22 September 1956)

- Irene (translation, Ugo Betti, 20 October 1957)

- Corruption in the Palace of Justice (translation, Ugo Betti, 19 January 1958)

- The Auction Sale (poem, 20 September 1958)

- The Primal Scene, As It Were: Nine Studies in Disloyalty (11 March 1958)

- Not a Drum Was Heard: The War Memoirs of General Gland (6 May 1959)

- One Flesh (translation, Silvio Giovaninetti, 12 June 1959)

- The Land Where the King Is a Child (translation, Henry de Montherlant, 3 October 1959)

- Musique Discrète: A Request Programme of Music by Dame Hilda Tablet (with Donald Swann, 27 October 1959)

- The House on the Water (translation, Ugo Betti, 3 February 1961)

- A Hospital Case (translation, Dino Buzzati, 22 November 1961)

- The America Prize (translation, Dino Buzzati, 18 June 1964)

- Zone 36 (translation, Dino Buzzati, 22 March 1965)

- The Complete Lessons of the War (poems, 14 February 1966)

- The Advertisement (translation, Natalia Ginzburg, 24 September 1968)

- Summer (translation, Romain Weingarten, 3 October 1969)

- The Two Mrs. Morlis (translation, Luigi Pirandello, 8 November 1971)

- The Strawberry Ice (translation, Natalia Ginzburg, 21 January 1973)

- Room for Argument (translation, Luigi Pirandello, 7 January 1974)

- The Wig (translation, Natalia Ginzburg, 23 March 1976)

- Like the Leaves (translation, Giuseppe Giacosa, 24 May 1976)

- Duologue (translation, Natalia Ginzburg, 3 January 1977)

- The Soul Has Its Rights (translation, Giuseppe Giacosa, 22 June 1977)

- Sorrows of Love (translation, Giuseppe Giacosa, 23 October 1978)

- Moby Dick (new production of 1947 play, 2 February 1979)

- I Married You for Fun (translation, Natalia Ginzburg, 7 January 1980)

It's likely some of the dates are incorrect, owing to frequent rebroadcasts and re-adaptations, and I've yet to find a record for the broadcast in 1953 of Reed's collaboration with the composer Elizabeth Lutyens on her BBC-commissioned Westminster Abbey. Still, this should be a fairly accurate and (almost) plenary list.

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

Really excellent finds this week. The first was only a short quote by Elizabeth Bowen, which mentions Reed. Sorting out the context for that will require a little more time to nail down all the corners.

But the other was in volume 7 of Theatre World Annual (London), which covers June 1st, 1955 to the 31st of May, 1956. It includes reviews and pictorials for two of Henry Reed's adaptations of Ugo Betti's plays, which were performed in London in the fall of 1955. The first of these was The Queen and the Rebels, which opened at the Haymarket Theatre on October 26th. Theatre World editor, Frances Stephens, called Reed's translation "taut and effective." Pictures by Angus McBean (apologies for my poor scans):

A moment from the opening scene of the play, which takes place in a large hall in the main public building in a hillside village near the frontier. Raim (Duncan Lamont) is interrogating a number of travellers, who have been forcibly held up at this remote spot by the revolutionary forces; among them Argia (Irene Worth, center. Later, left alone, Argia, a prostitute from the neighboring town, reveals that she had made the journey specially to find Raim. [Page 73.]

Raim indulges in some indiscreet talk with one of the travellers, only to discover later that he is Commissar Amos of the Revolutionary Party (Leo McKern, right)

The Queen, whose only desire is to get away, believes pathetically that Argia will help her. At the last moment Argia relents and helps her to escape the trap laid by Raim. The soldiers wrongly think that it was Argia who was trying to escape and report to Amos, who already has his suspicion about this unknown woman. He begins to question her. [Page 74.]

It is now obvious that the revolutionaries are convinced that Argia is the Queen and for the moment she revels in deceiving Biante, the General of the revolutionary forces, who has come back severely wounded from the fighting in the hills (Alan Tilvern).

The Queen has already been captured and having, through Argia's influence, gained a little courage, she is at last brave enough to take her own life. But Argia has now lost the one witness who might have saved her. She is sentenced to death, and later refuses to sign a trumped-up confession. [Page 75.]

In contrast to the intensity of Betti's Queen is Reed's "charming" translation of Summertime, which premiered at the Apollo Theatre, London, on November 9th, 1955. Pictures by Armstrong Jones:

Francesca (Geraldine McEwan, left) is determined to marry Alberto (Dirk Bogarde, right). She entices him, reluctantly, to a picnic in the mountains, where he confesses he has already innocently compromised himself with a girl in the city. (Centre: Michael Gwynn as the Doctor.) [Page 79.]

Aunt Ofelia (Esma Cannon), who is Alberto's aunt, and Aunt Cleofe (Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies) aunt to Francesca. These two have been watching the proceedings from a distance. Aunt Cleofe is anxious for Francesca to marry the young doctor, but in the end—as one might have expected—the girl forgives Alberto and the unfortunate young medico is sent packing.

|

1528. Manning, Hugo. "Recent Verse." Books of the Day, Guardian (Manchester), 31 July 1946, 3.

Manning feels that 'Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship.'

|

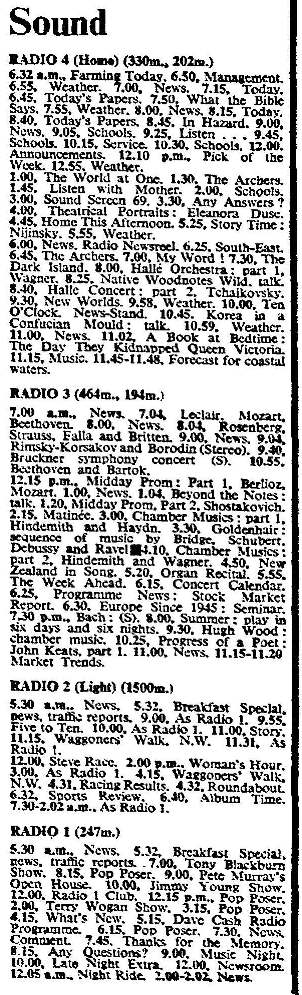

Times (London), "Radio 3," Sound, 3 October 1969, 19. "8.00, Summer: a play in six days and six nights." Play by Romain Weingarten, translated from the French and adapted for radio by Henry Reed.

|

1527. Rosenthal, M.L. "Experience and Poetry." Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review (New York), 17 October 1948, 28.

Rosenthal says Reed shares with Laurie Lee 'that unhappy vice of young intellectuals—a certain blandness of which the ever-simple irony is a symptom.'

|

Several books mention Reed's translations of Ugo Betti dramas as being produced for the London stage in 1955. Stallworthy, for instance, says in the Dictionary of National Biography: "Several of his translations found their way into the theatre, and in the autumn of 1955 there were London premières of no fewer than three." Quite an accomplishment. Reed adapted quite a few of Betti's plays for radio, however. So many in fact, that I am frequently confused as to the order they were produced.

Betti's play La Regina e gli Insorti was written in 1949. Commissioned by the BBC's Third Programme, Reed translated and adapted the play for radio, and The Queen and the Rebels was broadcast on October 17, 1954. The radio versions of all three plays were produced by Donald MacWhinnie.

Next came Betti's L'Ainola Bruciata, written 1951-52. Translated as The Burnt Flower-Bed, the play was broadcast on the Third Programme on January 3, 1955.

The third play, Summertime, began as Il Paese delle Vacanze (1937). It was broadcast as Holiday Land on the Third Programme on June 6, 1955.

The Burnt Flower-Bed was premièred live at the Arts Theatre, London, on September 9 of that year.

Subsequently, The Queen and the Rebels opened at the Haymarket Theatre, London, on October 26.

Finally, a version of Holiday Land was revised as Summertime, opening at the Apollo Theatre, London, on November 9, 1955.

Oddly enough, Reed's autobiographical entry for Who's Who mentions the publication of these translations as Three Plays (1956), but neglects any of the London stage productions. It does, however, make note of Betti's Crime on Goat Island being 'staged NY 1960', but the only notable production of Goats in New York (starring Laurence Harvey, Uta Hagen, and Ruth Ford) was also in 1955, not 1960.

And as a footnote, Reed's biographical entries in Contemporary Authors and Contemporary Poets both list a play titled Summertime as being produced for radio in 1969. This is actually a play called Summer, written by the French playwright Romain Weingarten, and translated by Reed. Summer was broadcast on Radio 3 on October 3, 1969.

A typescript for Summer resides in the Richard L. Purdy Collection of Thomas Hardy, in the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts department of Yale University (#809).

|

1526. Blunden, Edmund. "Poets and Poetry." Bookman, n.s., 1, no. 4 (July 1946): 14-15.

Edmund Blunden says Reed's Lessons of the War poems 'have captured something of the time-spirit and ambiguity of the recent war in a style of wit and deep feeling united.'

|

Diehard fans of Joan Plowright (or Natalia Ginzburg) may be interested in these posters offered by the National Theatre Archive. They're from the 1968-69 run of Ginzburg's play, The Advertisement, translated and adapted by Reed. The production was directed by Donald MacKechnie and Sir Laurence Olivier, and starred (besides Dame Joan) Suzanne Vassey, Louise Purnell, Edward Petherbridge, Anna Carteret, and Sir Derek Jacobi.

The National Theatre also has an extensive, searchable catalog of performances and items in their archives.

|

1525. "Reed, Henry," Publishers Weekly, 152, no. 15 (11 October 1947), 1945.

A note on the publication of the American edition of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

In 1933, a small theatre group in Birmingham, England, staged a production of Molière's L'Avare ( The Miser) at the Church House, High Street, Erdington ( pictured here). The company called themselves after the name of the house where they rehearsed: The Highbury Players. They had begun in 1924 as an artistic branch of the local Independent Labour Party, originally meeting to read stage plays aloud, but eventually forming the Highbury Little Theatre.

An excerpt from the book Highbury Little Theatre: A Beginning, written in 1946, describes the early efforts of the organization after their first play in 1925:

In the next twelve years the work undertaken included the following full length plays: Conflict, Much Ado about Nothing, Pygmalion, Heartbreak House, The Show, The Roof, Escape, The Skin Game, A Hundred Years Old, Pleasure Garden, Othello, The Circle of Chalk, The Sleeping Clergyman, and L'Avare in a new English translation by John English and Henry Reed—this was in 1932.

Mr. John English, OBE, one of the original members of the group, would go on to become a trustee of the Highbury Theatre Centre, and would help found the Midland Arts Centre.

There can be little doubt that the Highbury Players' co-translator of Molière's L'Avare was our Henry: the odds of coincidence are just too great. Henry Reed was born and raised in Erdington, was a vocal Socialist, and concentrated on French (and Latin) throughout his education, from King Edward VI Grammar School, all the way through his years at the University at Birmingham, which happen to coincide with the play's production.

|

1524. Reed, Henry. Letters to Graham Greene, 1947-1948. Graham Greene Papers,

1807-1999. Boston College, John J. Burns Library, Archives and Manuscripts Department, MS.1995.003. Chestnut Hill, MA.

Letters from Reed to Graham Greene, including one from December, 1947 Reed included in an inscribed copy of A Map of Verona (1947).

|

In parsing through the new BBC Programme Catalogue, I've turned up five radio plays Reed translated late in his career. One is later, in fact, than even Reed's reworking of Moby Dick in 1979. And he's credited with none of them in any bibliography I've seen (not even the exhaustive Contemporary Authors entry from 1999). Not surprisingly, the plays are all adaptations from Italian, Reed's adopted mother tongue. Here are the details, in chronological order:

Room for Argument, by Luigi Pirandello. Broadcast on Monday, January 7, 1974 at 8:00 p.m., Radio 4.

Like the Leaves, by Giuseppe Giacosa, broadcast Sunday, May 30, 1976 at 2:30 p.m., on Radio 4. (The Programme Catalogue has Monday, May 24, but the London Times disagrees. Word Aloud also has the 30th.)

The Soul Has Its Rights, by Giuseppe Giacosa. Broadcast on Wednesday, June 22, 1977 at 3:05 p.m., Radio 4.

Duologue, by Natalia Ginzburg, broadcast on Tuesday, September 20, 1977 at 9:30 p.m., Radio 3. (The Catalogue says January 3rd. Duologue is listed in the Sound Archive catalogue, but is undated. I'm double-checking.)

I Married You for Fun ( Ti Ho Sposato per Allegria), by Natalia Ginzburg. Broadcast Monday, January 7, 1980 at 7:45 p.m., on Radio 4, and repeated Saturday, January 12 at 2:30 pm. ( Word Aloud confirms. Also in the Sound Archive catalogue.)

Because I'd never seen these titles before, they stood out like sore thumbs. But I'd say, even if that's all I turn up, the Programme Catalogue has already started earning its keep.

|

1523. Reed, Henry. "Simenon's Saga." Review of Pedigree by Georges Simenon, translated by Robert Baldick. Sunday Telegraph (London), 12 August 1962, 7.

Reed calls Pedigree a work for the "very serious Simenon student only," and disagrees with the translator's choice to put the novel into the past tense.

|

In the year 1737, upon receiving word of the impending production of a particularly unfavorably satire of the rule of King George II, British Parliament passed the Theatrical Licensing Act, requiring that no person shall for hire, gain or reward, act perform, represent, or cause to be acted, performed or represented any new interlude, tragedy, comedy, opera, play, farce, or other entertainment of the stage, or any part of parts therein; or any new act, scene or other part added to any old interlude, tragedy, comedy, opera, play, farce or other entertainment of the stage, or any new prologue or epilogue, unless a true copy thereof be sent to the Lord Chamberlain of the King's household for the time being, fourteen days at least before the acting.... The Act ( full-text) called for the Lord Chamberlain and his Examiners of Plays to review and, where necessary, censor potential scripts before they reached the stage, with the intent of protecting the corruptible public. At the time, plays were already restricted to performances in theatres which had been granted royal patents. The Patent Act was repealed in 1843, but the Licensing Act remained intact until 1968.

Reed had adapted Ugo Betti's play, Crime on Goat Island, for the BBC's Third Programme in 1956. His translation had already appeared on the stage in 1955, at New York's Fulton Theatre. In 1957, however, a production was planned for the Oxford Playhouse, which ran into a "spot of bother" with the Lord Chamberlain's Office.

A very helpful gentleman at the British Library, Arnold Hunt, emailed me that the Manuscript Collections contain the original typescript submitted for examination (with the famous blue pencil marks of the censors), as well as additional correspondence detailing the debate over Reed's version of Betti's play. Mr. Hunt writes: “On 3 November 1957, the Assistant Examiner, St. Vincent Troubridge [a descendant of Lord Nelson], reported that he was not prepared to recommend the play for licence. 'The story of this play, condensed into a couple of sentences, is that to the widow of a Professor living on a remote goat-farm with her daughter and sister-in-law, there appears an attractive young man, claiming to have been friendly with the Professor in a war-time captivity. He proceeds to have sexual intercourse with all these three closely related women in turn, the widow on the first night of his arrival. A few weeks later they murder him down a well. This to my mind is a great deal too farmyard to be permissible in common decency on the public stage.'” The examiner's synopsis is fair, even if he was taking his responsibilities a bit too seriously (read more about how censorship shaped modern British theatre). The script was eventually deemed "'sordid and revolting,' but not injurious to morals," and the play was granted a license to be performed, hinging on the removal of one passage, which Troubridge described as 'sodomy in reverse, about goats trying to make physical love to their goatherds.' Angelo, the scroundrel of the play, tells a story of how goats in his country sometimes fall in love with their goatherds: And eventually the shepherd begins to understand, and after a little while they... make love, there in the meadows, pressing close together, closer than a man and woman even. (Act I, scene iv.) To the credit of his station, the Lord Chamberlain himself, the Right Honourable Lawrence Roger Lumley, 11th Earl of Scarborough, commented "I don't feel very strongly about the ordinary sex part, but I do draw the line at the goats."

(Coincidentally, the composer Donald Swann, who wrote the music for Reed's Hilda Tablet plays, mentions his regret at never having anything of his banned by Lord Scarborough, whom he called a "charming chap.")

Crime on Goat Island opened in Oxford on December 2nd, 1957. The following day, the Times' special correspondent reported weakness in Betti's plot and doubt in Reed's script: "The jealousy between the three women, the division in the household: these are real enough. But as Betti and his translator Mr. Henry Reed handle them they subtract from the interest of the characters instead of adding to it." No mention is made, however, of lovesick goats (The Arts, 3 December 1957, 3).

A history of censorship and its effects on British theatre was published last year: The Lord Chamberlain Regrets: British Stage Censorship and Readers' Reports from 1824 to 1968 ( Amazon.com US).

|

1522. Reed, Henry. "Hardy's Secret Self-Portrait." Review of The Life of Thomas Hardy, by Florence Emily Hardy. Sunday Telegraph (London), 25 March 1962, 6.

Reed says this disguised autobiography is a "ramshackle work," but is still "packed with a miscellany of information not available elsewhere, and readers who care for Hardy will find it everywhere endearing, engaging, and full of his characteristic humour."

|

I have eight citations to articles written by or about Reed from the Radio Times, dating from the 1950s. Since the Radio Times is more or less the British TV Guide, I suspect there are a lot more references, but these are the only ones other folks have cited. (And one or two of them are suspect!)

So I wasted twenty or thirty minutes today, browsing online bookshops that deal in collectible magazines and periodicals. Even if they all don't turn out to contain anything of interest, it still wouldn't be entirely cheap to buy the issues outright. I'd rather have groceries.

My other option is to take a field trip to the Library of Congress in D.C., which is always productive, but a bit of an adventure for a hermit like myself. It would only cost me 20¢ per photocopy, and I would be able to peruse in relative leisure.

Photocopies are so sterile, though. Nothing like the feel of an old magazine: the brittle, yellow pages smelling warmly of neglected attics and dank basements.

The small treasure I found today was on the WordAloud website. WordAloud is a repository for information on radio broadcasts. They have airdates, synopsis, and credits for all sorts of BBC radio drama, including some of Henry Reed's. Hardy's "Battle of Trafalgar"? Never heard of it. Some adaptation of The Trumpet Major? "The Sergeant's Song"?

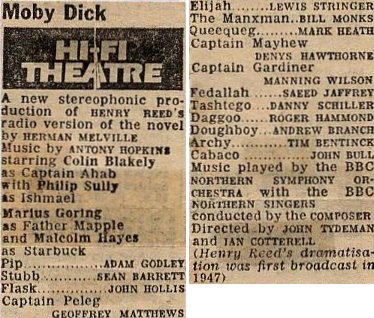

The prize among all these scraps and clues, was a clipping from a 1979 Radio Times, listing the credits for Reed's (stereophonic!) re-working of his 1947 radio adapation of Moby Dick:

Update: The London Times reveals that "The Battle of Trafalgar" was adapted for radio by Reed from Thomas Hardy's The Dynasts, which was orginally broadcast in its entirely as six ninety-minute episodes in June of 1951 (Savage, in British Radio Drama). Unfortunately, the Times was on strike at the time of the Moby Dick broadcast.

|

1521. Reed, Henry. "Leading a Dance." Review of Fokine: Memoirs of a Ballet Master, translated by Vitale Fokine. Sunday Telegraph (London), 26 November 1961, 6.

Reed finds Fokine's memoirs "very absorbing and intelligent."

|

I managed to break free of the apartment's gravity this afternoon, and drop into the University's main library for a few hours, to do some work without the Herculean distractions of cable television and an attention-starved cat. Currently, we're in the reading period which preceeds exams, the carrels are full, and the only sounds are the squeak of ungreased office chairs, the opening click and closing clack of serials binders being filed into, and the clearing of anxious throats.

I left the house without white index cards.

I'm actually fairly high-tech, filing citations into an online bibliography, but a laptop is still a bit clunky for walking up and down the stacks, looking for as-yet-unseen volumes. So I write everything down on index cards, first: white for the things I have a copy of, colors for wants and needs. When I find an item on a green or red or blue card, it gets tossed and a new, white, card gets written out with a description, and the database gets updated to an "Own?" Yes. Ridiculous, right? This is the system I came up with.

Plus, I throw away the sickly, yellow cards that come in the pack.

Last night I was trying to nail down a concrete date when Reed stopped working for the BBC Features Department: his last translation was broadcast in 1978 (Sorrows of Love, by Giuseppe Giacosa). But there was a nagging doubt that I had, somewhere in my pile of cites from the London Times, seen mention of a play I hadn't found anywhere else, which may have been later than '78.

Today, due to my lack of having white cards to fill out, I was catching up on plugging new entries into the database, instead. And, bam! There it was: The Strawberry Ice, by Natalia Ginzburg. Translated by Henry Reed for the BBC, and broadcast on January 24th, 1973.

It was a Wednesday afternoon.

|

1520. Reed, Henry. "Shocked into Life." Review of The Empty Canvas, by Alberto Moravia, translated by Angus Davidson. Sunday Telegraph (London), 19 November 1961, 7.

Of Moravia's most recent novel, Reed says "there is something unquestionably heroic about the whole enterprise."

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|