|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Italy"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

My efforts to track the poet Henry Reed through his early decades of the 1930s and 40s are often frustrated by the constant manifestations of another semi-famous "Henry Reed": a popular British band leader who seems to have made nearly daily appearances on the radio during that time. This doppelgänger's career only begins to fade out in the mid- to late-1940s, just as our poet's begins to rise.

It was probably owing to the overwhelming multitude of the Pretender's radio appearances which led me to overlook this article from the Manchester Guardian, in September, 1937: a first-person report—narrative, really—from the annual Piedigrotta music festival in Naples.

For a brief moment I feared it had been written by the musician, but before I even finished the first paragraph I realized it must be the Literary Reed: the ghost of Leopardi materializes; a paraphrase of Baedeker's Italy is inserted; there is a struggle with Italian dialect; Pompeii; and lastly—the clincher—there is a repetition of "to-morrow. To-morrow. To-morrow...".

Reed sounds very close to his subject here. So very close, the music is still ringing in his ears; so I think we shall have to update his timeline/map to include a visit to Naples in the first week of September, 1937:

PIEDIGROTTA

The Piazza di Piedigrotta in Naples is never properly to be called quiet, except occasionally between two and four in the morning. In the first week of September, while people are restlessly waiting for the Popular Song Festival, even this intermission is ignored. On the night of the festival itself one is not especially conscious of enormous noise, for it seems by this time that one has never known silence. Not far away from the radiant tunnel of lights in which the musical competitions take place Virgil lies in his mythical tomb, and in another direction, Leopardi lies in his real one. Do they ever turn in them on this night, one wonders?

The festa once had a ceremony, a ritualistic splendour, but it is not to be supposed that its participants today know that, or bother much about it, though they are happily conscious that their revels are tolerantly presided over by Santa Maria di Piedigrotta in the near-by church. The cook at the pizzeria has never heard of Charles III. The old man who even at this time tries to sell you bootlaces cares nothing for Charles's victory at Velletri in 1744. The tenor who sings the new songs might perhaps be interested to hear that Charles commemorated Velletri by instituting the festival at which he earns whatever he eats instead of bread and butter, but more probably he would merely smile and murmur during the introduction of the second verse that it would have happened anyway. And the information that "this huge fair was held every year with considerable magnificence till the fall of the Bourbon dynasty in 1859" would be greeted with huge derision. Considerable magnificence? Has not M------, the singer, introduced a perfectly splendid and gratuitous high D into the song of the year, a note it was thought would not be heard from a man in our lifetime? Are not the fireworks louder and brighter and longer and cheaper than ever before? Have not more new combinations of instruments been evolved this year than it was ever believed possible? Did you ever think to hear a trumpet and harp duet before? Magnificence?

Every one of us has a Chinese lantern or an impossible nose or a paper hat. We all have those things that you blow out in other people's faces, or those things that you shake round in other people's ears. If you have unlimited money there is unlimited food. Over certain gelaterie there are still old-fashioned flaming gas-jets, but their noise cannot be separately heard as we feverishly lick huge slabs of ice-cream under them. For three singers are I passing in a cart, accompanied by a string octet. To me the words are unintelligible, though I am glad to hear the dialect word "Scetà," which comes in every Neapolitan song, I should think, and means "Wake up." I am deeply impressed and unnecessarily give the waiter a tip. As we hurry away I am severely rebuked for this extravagance by young Neapolitan friends. Arguing furiously, we all step with care over a happily sleeping tramp. I explain that I am not entirely penniless and that it is a season if not of peace on earth at least of goodwill to men. This is considered a silly remark, and after another debate shouted over the noise of bagpipes (bagpipes!) we go on. But the youngest of our party has disappeared. He comes panting up three minutes later, having, by what miracle of cajolery or menace I cannot find out, recovered my penny from the waiter. He gives it to his eldest brother to keep for me.

The tunnel cut through the hill of Posilipo is brightly lit, and one can dance in it, since no automobile will be allowed to pass through it until to-morrow. The wise will have, learned the words and tunes of the songs from the leaflets that have been going about for the last few weeks. Anyone would have taught you the tunes on the violin or the guitar (there is, it appears, no piano in Naples). Then you can join in when the carts containing their little bands come round to catch your approbation.

There is no doubt about which is the best song. Surely a finer librettist than Di Giacomo has arisen in—what is his name, did you say?—the poet who has been so inspired as to mention all the islands in the bay in the same song, and the ghosts of dead lovers at Pompeii as well. And even Tagliaferri could not produce phrases more yielding to the individual choice of vocal ornament than those that M------ is embellishing with his brilliant "mordenti" at the moment. (They say he really comes from Baia, but that is only just round the corner, and it is more than likely that his grandmother came from Naples.)

One must, of course, discriminate with care. The song of the year may be one of those that will not just circle the bay and die after a short excursion to Rome. It may be another "Funiculi, funicula," and go round the world for years and years. But even if nothing historic emerges the individual conscience need not worry. For it will all be a good racket while it lasts. The night will grow louder and louder, and we shall meet more and more new people, who Will remember you because you are English and odd, though you cut them to-morrow.

To-morrow. To-morrow everyone is a bit hoarse. The lights are kept up the next night, for there is a natural attempt to make a good party last as long as it can. But it is rather a hopeless one, and the piazza next day has rather the aspect of an untalking film. In the reaction from the unspeakable recklessness that has led you the night before to embark upon ices, melons of all kinds, lemonade, several "veri vini," and great late figs you have become cowardly, and sit with your companions under the tawny lights of the fountain chewing monkey-nuts. They have forgotten the festa and are reverting to a game of more permanent exhilaration, that of trying to teach you to say "Vedi Napoli e poi muori" in the dialect. "Vega Nabul' u puo' muo'" it sounds like. The last two words are especially hard, and you create much amusement by them.

Henry Reed.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

Well, what have we here? In the pages of Italy Writes: A Review for Those Who Read ( L'Italia che scrive; rassegna per coloro che leggono), the journal of the Leonardo Foundation of Italian Culture, Rome ( Fondazione Leonardo per la cultura italiana), an announcement from a 1947 Italian writers' festival ( Settimana degli scrittori):

Dal 24 al 26 settembre si è svolta, sempre in Perugia una Settimana degli scrittori, con relazione di Giacomo Debenedetti sul Teatro e romanzo della realtà e teatro e romanzo dell'esistenza. Erano presenti il poeta inglese Henry Reed, il prof. Kardos, studioso dell'umanesimo in Ungheria, nostri letterati, critici, scrittori e filosofi come Bellona, Toschi, Della Volpe, Tecchi, Banfi, Contini, Capitini, Bigiaretti, Mila, Ronga, Vigorelli, Cantoni, D'Amico, Pandolfi, Guerrieri.

Which roughly translates as: "From September 24 to 26 took place, again in Perugia a Week of the writers, with relation of Giacomo Debenedetti on the theatre and novel of truth, and the theatre and novel of life. Those present included the English poet Henry Reed, Professor Kardos, a scholar of humanism in Hungary, our writers, critics, and philosophers such as Bellona, Toschi, Della Volpe, Tecchi, Banfi, Contini, Capitini, Bigiaretti, Mila, Ronga, Vigorelli, Cantoni, D'Amico, Pandolfi, Guerrieri."

Emphasis mine, of course. If anyone has a better grasp of Italian, I'd encourage you to leave a comment or drop me an e-mail!

We had previously found Reed talking about having attended the Festival of Sacred Music in Umbria, held at about the same time, from September 21 through October 5, 1947. I believe the concurring writers' festival in question has evolved into the Umbria Libri, an annual book festival in Perugia.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

Henry Reed was an inveterate Italophile, who probably spent more time thinking about being in Italy than he actually spent there, visiting. Take for example his 1942 poem, " A Map of Verona," in which he pores over a map of the city, yearning to return. Reed had studied Latin in grammar school , winning the Temperley Latin prize and a scholarship to the University of Birmingham. His Latin must have led him directly to the Italian poet, Leopardi, whose life he would later dramatize in two radio plays: The Unblest (1949), and The Monument (1950). By the outbreak of World War II, Reed's Italian was fluent enough to earn him a post as a translator at Bletchley Park.

Exactly how many times Reed visited Italy during his lifetime seems to need a bit more research. The two sources we have for this are Stallworthy's Introduction to the Collected Poems, and James S. Begg's thesis, "The Poetic Character of Henry Reed."

Stallworthy implies that Reed's father (Henry, Sr.) financed his son's first excursion to Naples in 1936, after Reed graduated as the University of Birmingham's youngest MA, and entered the workforce: 'Like many other writers of the Thirties, he tried teaching—at his old school—and, again like most of them, hated it and left to make his way as a freelance writer and critic. He began the research for a full-scale life of Thomas Hardy, and his father financed a first trip to Italy.' Beggs, however, states that Reed's first trip was in 1934, after his BA, and that the 1936 visit was his second, returning again in 1939.

Regardless of how many times Reed actually visited Italy, there is the question of how he got there. How, exactly, did an Englishman on holiday in the mid-1930s travel to Italy? It seems unlikely that he would have taken advantage of the new world of passenger air travel, though it is possible. Much more likely, however, is that he traveled by rail or boat, or both.

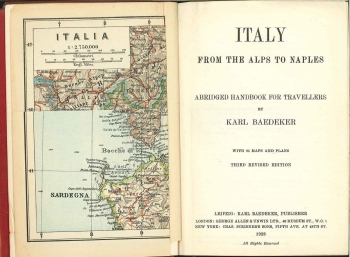

Professor Adele Haft has suggested in her article "Henry Reed's Poetic Map of Verona: (Di)versifying the Teachings of Geography IV" ( Cartographic Perspectives 40 (Fall 2001): 32-50) that Reed's much-studied map of Verona (.jpg) was most likely from a popular guidebook at the time; possibly the 1928 or 1932 editions of Baedeker's Italy: From the Alps to Naples, or the Blue Guide Northern Italy: From the Alps to Rome (1924). Let's consider Baedeker's suggestions (.pdf) for travel:

C. Routes from England to Italy.

By Railway. The following are the chief routes from London to Milan (through-carriages from the Continental port, unless otherwise stated). Fares are subject to frequent alterations. — Travellers are strongly recommended to insure their luggage (at any of the tourist agencies or on application at the railway booking-office).

(1) Viâ Calais, Laon, and Berne, 794 M., by the Anglo-Swiss-Lötschberg-Italian Express daily in 23 hrs. Fares 7 l. 10 s. 1 d., 5 l. 4 s. 9 d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 13 l. 4 s. 9 d., 9 l. 9 s. 1 d..

(2) Viâ Calais, Laon, Bâle, Lucerne, and the St. Gothard Tunnel, 842½ M., by the Anglo-Swiss-Gothard-Italian Express daily in 22¾ hrs. Fares as above.

(3) Viâ Calais, Paris, and Lausanne, 806½ M., by the Simplon-Orient Express (train de luxe, supplementary fare payable) daily in 25 hrs. (7 l. 6 s. 11 d.) and the Direct Orient Express in 27 hrs. (fares as above).

(4) Viâ Bologne, Paris, the Mont Cenis Tunnel, and Turin (change), 874 M., by the Rome Express (train de luxe) daily in 27 hrs. (supplementary fare payable). Ordinary fares 7 l. 12 s. 6 d., 5 l. 5 s. 6 d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 13 l. 7 s. 5 d., 9 l. 10 s. 6 d..

(5) Viâ Ostend, Brussels, Strasbourg, Bâle, and Lucerne, 845½ M., daily in 28¾ hrs. Fares 6 l. 18 s. 2 d., 4 l. 15 s. 4 d.

(6) Viâ Dunkirk, Lille, Strasbourg, Bâle (change), and Lucerne, 848 M., daily in 31 hrs. Fares 6 l. 8 s. 6 d., 4 l. 4 s. 8 d., 3 l. 2 s. 1 d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 10 l. 17 s. 3 d., 7 l. 6 s. 0 d., 5 l. 8 s. 4 d.

By Air. The journey from London to Italy may be accomplished by the aeroplanes of the French Air Union as far as Marseilles (viâ Paris and Lyons; daily, except Sun., in 11 hrs., including motor-car journeys; fare 12 l. 15 s.). There is also a service from Paris to Bâle, Zürich, and Lausanne. Comp. p. xvii.

By Sea. Regular sailings are made by the liners of the under-mentioned companies. The fares average 17-25 l. and the voyage lasts about 8 days. Special tourist fares are offered during the summer, particulars of which may be had on application to the companies (London addresses given below) or to any travel agency (C.I.T., p. xvi; Thos. Cook & Son, Berkeley St., Piccadilly, etc.; American Express Co., 6 Haymarket, S.W. 1; etc.).

Orient Line (5 Fenchurch Avenue, E.C. 3) from London to Naples. — Nederland Royal Mail Line (60 Haymarket, S.W. 1) from Southampton to Genoa. — Ellerman's City and Hall Lines (104-106 Leadenhall St., E.C. 3) from Liverpool to Naples. — Nippon Yusen Kaisha (25 Cockspur St., S.W. 1) from London to Naples. — German Africa Service (Greener House, Haymarket, S.W. 1) from Southampton to Genoa.

Looking to Reed's radio plays for some clue, we find a mention of trains to Rome and Naples in the opening of Return to Naples (1950):

Narrator: But that was not yet in Naples, you remember; that was in Rome. That morning, as the train moved South into the early sunlight of the campagna, you had drifted into conversation with an elderly doctor. He invited you to breakfast when you got to Rome. You went. You met his wife. You ate. You drank. And you were told you might stay in their apartment instead of going to a hotel. You accepted. Then you were left to doze off the effects of the journey in the misty heat of the shuttered salone. You slept. You woke. And you saw Alberto for the first time: fat, white-clad, tiptoeing gingerly across the room on his eternal blisters . . . Later that day, he wrote a letter which you were directed to give to his mother in Naples. It began, Carissima Mamma . . .

Alberto: 'Dearest Mamma, This young man, who will present my letter to you, is a very great friend of mine, whom I met this afternoon at the house of Doctor Cappocci . . .'

Narrator: That afternoon you had walked together to the Porta Pia, his small fat hand had created a pool of sweat in the crook of your arm . . .

Alberto: '. . . His name is Enrico. He is English, and is staying with Doctor Cappocci, and next week he is going to Capri. On the way, he will call on you in Naples. Please receive him into our home with the greatest kindness. Your most affectionate Alberto.'

Narrator: That letter, which was never delivered, you kept for many years, together with Alberto's other gifts: the sprig of unpolished coral, the slab of marble pavement from Tarquinia, and the life of Admiral Gravina, which sixteen years later you have yet to read . . .

There was no need to deliver the letter of introduction, for in the end Alberto's father and brother came up to Rome to fetch you, and you all travelled to Naples together.

(faint continental train noises in background)

So, putting two and two together, as it were—if we rely on Reed's autobiographical inspiration for his play—we can place him on the Milan-Naples train through Italy, via Switzerland and France, headed south to Rome, on his way to Naples and the island of Capri. And Reed specifically mentions that his titular "return" to Naples took place two years later, following the Italian conquest of Abyssinia (Ethiopia), so the 1934 and 1936 dates would seem correct. The play places Reed's third visit in 1939, a year before Italy declared war on France and Great Britain. All in all, the "H." in the play visits his adopted Neapolitan family a total of five times, over the course of two decades.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|