|

Birmingham in the 1930sHere's a customized Google Map providing interactive literary landmarks for Birmingham, England, during the 1930s, which intersects nicely in several places with our own map of Henry Reed's life. This map appears to have been created in conjunction with a recent screening of As I Was Walking Down Bristol Street (1983), a short documentary film on the Birmingham Group of writers and artists. More detailed information about the places and people described is provided on mike in mono's blog, with spectacular posts on the authors Walter Allen and John Hampson; Gordon Herickx, the sculptor; the Highfield estate (Louis MacNeice lived in a flat above the coachhouse while he was a professor at the University of Birmingham); and Professor E.R. Dodds.

Lovell's FarmI see the Google Street View car has been busy, snapping new pictures of locations across the U.K., from verge and curb. A few of these places are pertinent to our aims, such as Henry Reed's unassuming childhood home, in New Street, Erdington. Also in Erdington, along the High Street, is the former Church House (now a Savers, "Where the Smart Shopper Shops," I'm sorry to say), where Henry Reed first took to the stage, with the Highbury Players, in the early 1930s. Over in Bedford, we catch a glimpse the house in De Parys Avenue, where, from September 1943 through February 1944, following Italy's surrender, Reed attended a course at the Japanese Code School organized by the Inter-Service Special Intelligence School, as part of Bletchley Park's codebreaking efforts.

A whole gaggle of places turn up now in Dorset, including the front gate to Thomas Hardy's home, Max Gate, in Dorchester, where Reed paid a call on Hardy's widow in the autumn of 1936, while he was still hoping to produce a biography of his hero. Then, we arrive outside Yetminster's stately, 17th-century Gable Court, where Reed spent a very productive year between 1949 and 1950, until he moved to London. It was while at Gable Court (currently listed as "Milford House" at British Listed Buildings online, but the sign on the gate clearly still says "Gable Court," today) that Reed wrote his radio dramas based on the life of the Italian poet and philosopher, Giacomo Leopardi: The Unblest (first broadcast May 9, 1949), and The Monument (March 7, 1950). Best of all, Google Street View actually helped me resolve a minor detail: the exact location of Lovell's Farm (click the minus "-" sign to zoom out) in Marnhull, which I simply could not seem to place. Reed, accompanied by Michael Ramsbotham, rented this ample farmhouse after World War II, from as early as August or September, 1946, until possibly as late as their move to Gable Court, in early 1949. There, according to Jon Stallworthy's introduction to the Collected Poems, while Ramsbotham worked on a novel (perhaps The Parish of Long Trister), Henry Reed researched his never-completed Hardy biography, wrote book reviews for The Listener, and occasionally traveled to London to give literary and literate talks on the BBC's Third Programme. His first full-length play for the BBC, a radio adaptation of Moby Dick, was most likely completed at Lovell's Farm, being broadcast on January 26, 1947. When the play was published later that year, Reed's Preface was signed from Marnhull. I never would have found the farm, but for the detailed description in An Inventory of Historical Monuments in the County of Dorset (1970), which allowed me to pinpoint it in Google Maps' aerial view. Even in dry, planed-and-sanded language, the house sounds absolutely heavenly: LOVELL'S FARM (77511938), 1,000 yds. N.W. of the church [St. Gregory's], is of two storeys with dormer-windowed attics; it has walls of coursed rubble with ashlar dressings, and roofs of tiles and stone-slates. The S. range has a symmetrical S. front and is probably of the 17th century. It was extended to the E. in the 18th century and a wing was built northwards from the E. end of the extension early in the 19th century. The original part of the S. front has a rubble plinth and is of two bays with a central doorway; above the ground-floor window heads is a continuous weathered and hollow-chamfered string-course. The windows of both storeys are of three square-headed lights with recessed and beaded stone architraves and beaded mullions; the doorway surround is similar, with the addition of a fluted keystone. Over the doorway is a segmental wooden hood with a dentilled cornice and shaped brackets. The E. extension has neither plinth nor string and the window surrounds are of wood. The N. wing is of roughly coursed rubble, with tiled roofs with stone-slate verges; the windows are of wood. Projecting N. from the W. part of the original S. range is a gabled N.W. wing. It has wood-framed windows with 18th-century leaded iron casements on the ground and first floors; the attic window has modern casements; all these openings are spanned by long timber lintels. In the E. wall is a small circular first-floor window with a recessed ashlar surround and radial leaded glazing. Inside, the room at the W. end of the original range has 18th-century fielded panelling, in two heights, with moulded dado rails and cornices. In a cupboard beside the 18th-century fireplace are preserved the chamfered stone jamb and continuous wooden bressummer of an open fireplace. S. of the fireplace is an external doorway, now blocked up and used as a cupboard. The partition between this room and the entrance vestibule is of plank-and-muntin construction with beaded edges. Several ground-floor rooms have deeply chamfered ceiling beams. A window pane has a scratching of 1738. (v. 3, Pt. 2, "Central Dorset," p. 158) After all my virtual driving around Marnhull, grinding gears going forwards and reversing, confirming the location was as simple as another search in British Listed Buildings. I've also gathered some screenshots taken in Street View into a Flickr set.

Behind This DoorLast month, Google Maps went live with their Street View service for select cities in the UK, including Birmingham, Cambridge, London, and Oxford (see the announcement on Google's LatLong blog). This adds another dimension to our map of "The Life and Times of Henry Reed," and will hopefully allow for more accurate placemarking, since Google's street addresses are approximate, and often off by as much as a city block.

The first thing I went looking for was Reed's London flat on Upper Montagu Street, where he lived from 1957 until his death in hospital, in 1986. Here's a small, interactive widget—click the + sign to zoom, and the arrows to sidestep—you can even pop around the northwest corner to the chemist's, on Crawford Street! Zooming in, of course, we can go right up to the front door: The fact that the building is still extant is important, since it means that Reed stands a chance at one day getting his own memorial Blue Plaque from English Heritage, perhaps for the centenary anniversary of his birth, in 2014.

Henry Reed Google MapPlease, keep in mind that this is a work in progress, extremely rough. I've been toying around with it since last fall, when I was trying to find the original location of Bowen's Court (#15, below). Allow me to present The Life and Times of Henry Reed: A Google Map (βeta). Click this image to go the map page, and then you can follow the labeled locations, zoom in and out, and switch between road map and satellite views. And of course, remember, "Maps are of time, not place."

I used one of the Google Maps API Demos to kludge the map into The Poetry of Henry Reed pages. It should be relatively browser-friendly, though I've really only test-driven it in Firefox. If you have problems, try looking at my original Henry Reed map in Google. I've already received one comment which allowed me to amend my timeline of Reed's life, and I'm updating the map on almost a daily basis.

Innocent AbroadHenry Reed was an inveterate Italophile, who probably spent more time thinking about being in Italy than he actually spent there, visiting. Take for example his 1942 poem, "A Map of Verona," in which he pores over a map of the city, yearning to return. Reed had studied Latin in grammar school , winning the Temperley Latin prize and a scholarship to the University of Birmingham. His Latin must have led him directly to the Italian poet, Leopardi, whose life he would later dramatize in two radio plays: The Unblest (1949), and The Monument (1950). By the outbreak of World War II, Reed's Italian was fluent enough to earn him a post as a translator at Bletchley Park.

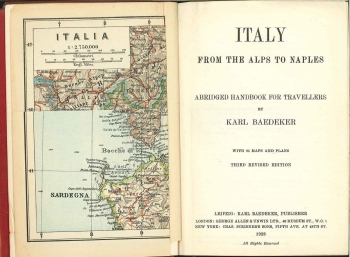

Exactly how many times Reed visited Italy during his lifetime seems to need a bit more research. The two sources we have for this are Stallworthy's Introduction to the Collected Poems, and James S. Begg's thesis, "The Poetic Character of Henry Reed." Stallworthy implies that Reed's father (Henry, Sr.) financed his son's first excursion to Naples in 1936, after Reed graduated as the University of Birmingham's youngest MA, and entered the workforce: 'Like many other writers of the Thirties, he tried teaching—at his old school—and, again like most of them, hated it and left to make his way as a freelance writer and critic. He began the research for a full-scale life of Thomas Hardy, and his father financed a first trip to Italy.' Beggs, however, states that Reed's first trip was in 1934, after his BA, and that the 1936 visit was his second, returning again in 1939. Regardless of how many times Reed actually visited Italy, there is the question of how he got there. How, exactly, did an Englishman on holiday in the mid-1930s travel to Italy? It seems unlikely that he would have taken advantage of the new world of passenger air travel, though it is possible. Much more likely, however, is that he traveled by rail or boat, or both. Professor Adele Haft has suggested in her article "Henry Reed's Poetic Map of Verona: (Di)versifying the Teachings of Geography IV" (Cartographic Perspectives 40 (Fall 2001): 32-50) that Reed's much-studied map of Verona (.jpg) was most likely from a popular guidebook at the time; possibly the 1928 or 1932 editions of Baedeker's Italy: From the Alps to Naples, or the Blue Guide Northern Italy: From the Alps to Rome (1924). Let's consider Baedeker's suggestions (.pdf) for travel: C. Routes from England to Italy. (1) Viâ Calais, Laon, and Berne, 794 M., by the Anglo-Swiss-Lötschberg-Italian Express daily in 23 hrs. Fares 7l. 10s. 1d., 5l. 4s. 9d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 13l. 4s. 9d., 9l. 9s. 1d.. (2) Viâ Calais, Laon, Bâle, Lucerne, and the St. Gothard Tunnel, 842½ M., by the Anglo-Swiss-Gothard-Italian Express daily in 22¾ hrs. Fares as above. (3) Viâ Calais, Paris, and Lausanne, 806½ M., by the Simplon-Orient Express (train de luxe, supplementary fare payable) daily in 25 hrs. (7l. 6s. 11d.) and the Direct Orient Express in 27 hrs. (fares as above). (4) Viâ Bologne, Paris, the Mont Cenis Tunnel, and Turin (change), 874 M., by the Rome Express (train de luxe) daily in 27 hrs. (supplementary fare payable). Ordinary fares 7l. 12s. 6d., 5l. 5s. 6d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 13l. 7s. 5d., 9l. 10s. 6d.. (5) Viâ Ostend, Brussels, Strasbourg, Bâle, and Lucerne, 845½ M., daily in 28¾ hrs. Fares 6l. 18s. 2d., 4l. 15s. 4d. (6) Viâ Dunkirk, Lille, Strasbourg, Bâle (change), and Lucerne, 848 M., daily in 31 hrs. Fares 6l. 8s. 6d., 4l. 4s. 8d., 3l. 2s. 1d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 10l. 17s. 3d., 7l. 6s. 0d., 5l. 8s. 4d. By Air. The journey from London to Italy may be accomplished by the aeroplanes of the French Air Union as far as Marseilles (viâ Paris and Lyons; daily, except Sun., in 11 hrs., including motor-car journeys; fare 12l. 15s.). There is also a service from Paris to Bâle, Zürich, and Lausanne. Comp. p. xvii.By Sea. Regular sailings are made by the liners of the under-mentioned companies. The fares average 17-25 l. and the voyage lasts about 8 days. Special tourist fares are offered during the summer, particulars of which may be had on application to the companies (London addresses given below) or to any travel agency (C.I.T., p. xvi; Thos. Cook & Son, Berkeley St., Piccadilly, etc.; American Express Co., 6 Haymarket, S.W. 1; etc.).Orient Line (5 Fenchurch Avenue, E.C. 3) from London to Naples. — Nederland Royal Mail Line (60 Haymarket, S.W. 1) from Southampton to Genoa. — Ellerman's City and Hall Lines (104-106 Leadenhall St., E.C. 3) from Liverpool to Naples. — Nippon Yusen Kaisha (25 Cockspur St., S.W. 1) from London to Naples. — German Africa Service (Greener House, Haymarket, S.W. 1) from Southampton to Genoa. Looking to Reed's radio plays for some clue, we find a mention of trains to Rome and Naples in the opening of Return to Naples (1950): Narrator: But that was not yet in Naples, you remember; that was in Rome. That morning, as the train moved South into the early sunlight of the campagna, you had drifted into conversation with an elderly doctor. He invited you to breakfast when you got to Rome. You went. You met his wife. You ate. You drank. And you were told you might stay in their apartment instead of going to a hotel. You accepted. Then you were left to doze off the effects of the journey in the misty heat of the shuttered salone. You slept. You woke. And you saw Alberto for the first time: fat, white-clad, tiptoeing gingerly across the room on his eternal blisters . . . Later that day, he wrote a letter which you were directed to give to his mother in Naples. It began, Carissima Mamma . . . Alberto: 'Dearest Mamma, This young man, who will present my letter to you, is a very great friend of mine, whom I met this afternoon at the house of Doctor Cappocci . . .' Narrator: That afternoon you had walked together to the Porta Pia, his small fat hand had created a pool of sweat in the crook of your arm . . . Alberto: '. . . His name is Enrico. He is English, and is staying with Doctor Cappocci, and next week he is going to Capri. On the way, he will call on you in Naples. Please receive him into our home with the greatest kindness. Your most affectionate Alberto.' Narrator: That letter, which was never delivered, you kept for many years, together with Alberto's other gifts: the sprig of unpolished coral, the slab of marble pavement from Tarquinia, and the life of Admiral Gravina, which sixteen years later you have yet to read . . . There was no need to deliver the letter of introduction, for in the end Alberto's father and brother came up to Rome to fetch you, and you all travelled to Naples together. (faint continental train noises in background) So, putting two and two together, as it were—if we rely on Reed's autobiographical inspiration for his play—we can place him on the Milan-Naples train through Italy, via Switzerland and France, headed south to Rome, on his way to Naples and the island of Capri. And Reed specifically mentions that his titular "return" to Naples took place two years later, following the Italian conquest of Abyssinia (Ethiopia), so the 1934 and 1936 dates would seem correct. The play places Reed's third visit in 1939, a year before Italy declared war on France and Great Britain. All in all, the "H." in the play visits his adopted Neapolitan family a total of five times, over the course of two decades.

LibraryThing LocalLibraryThing (remember LibraryThing? We had a visit from Tim, back in the day) went live last week with a neat new app: LibraryThing Local. I don't usually Oo and Ah over stuff that's all Web 2.0ey, but this is pretty neat.

It's basically a mapping system which allows LibraryThing members to add "venues": libraries, bookstores, festivals, and other book-related locations and events. For instance, here's all the recently-added venues within five miles of The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. (zipcode 20540). Thingology has a post with a bunch of other examples. Users can bookmark their favorite spots, and libraries and bookstores can even officially sponsor the entries for their venues, if they didn't add themselves. Here's the LibraryThing blog announcement of the new service, and an update after the first 9,000 venues were added.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

!['[T]wo storeys with dormer-windowed attics; it has walls of coursed rubble with ashlar dressings, and roofs of tiles and stone-slates. The S. range has a symmetrical S. front and is probably of the 17th century.' Formerly Lovell's Farm, Burton St., Marhull, Dorset, in Google Street View. Google Street View](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4096/4769403773_62a2633002.jpg)