Exactly how many times Reed visited Italy during his lifetime seems to need a bit more research. The two sources we have for this are Stallworthy's Introduction to the Collected Poems, and James S. Begg's thesis, "The Poetic Character of Henry Reed."

Stallworthy implies that Reed's father (Henry, Sr.) financed his son's first excursion to Naples in 1936, after Reed graduated as the University of Birmingham's youngest MA, and entered the workforce: 'Like many other writers of the Thirties, he tried teaching—at his old school—and, again like most of them, hated it and left to make his way as a freelance writer and critic. He began the research for a full-scale life of Thomas Hardy, and his father financed a first trip to Italy.' Beggs, however, states that Reed's first trip was in 1934, after his BA, and that the 1936 visit was his second, returning again in 1939.

Regardless of how many times Reed actually visited Italy, there is the question of how he got there. How, exactly, did an Englishman on holiday in the mid-1930s travel to Italy? It seems unlikely that he would have taken advantage of the new world of passenger air travel, though it is possible. Much more likely, however, is that he traveled by rail or boat, or both.

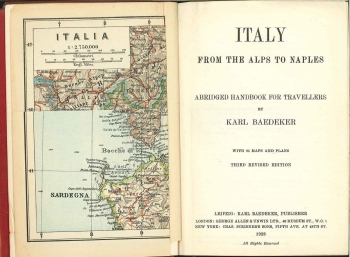

Professor Adele Haft has suggested in her article "Henry Reed's Poetic Map of Verona: (Di)versifying the Teachings of Geography IV" (Cartographic Perspectives 40 (Fall 2001): 32-50) that Reed's much-studied map of Verona (.jpg) was most likely from a popular guidebook at the time; possibly the 1928 or 1932 editions of Baedeker's Italy: From the Alps to Naples, or the Blue Guide Northern Italy: From the Alps to Rome (1924). Let's consider Baedeker's suggestions (.pdf) for travel:

C. Routes from England to Italy.

By Railway.

(1) Viâ Calais, Laon, and Berne, 794 M., by the Anglo-Swiss-Lötschberg-Italian Express daily in 23 hrs. Fares 7l. 10s. 1d., 5l. 4s. 9d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 13l. 4s. 9d., 9l. 9s. 1d..

(2) Viâ Calais, Laon, Bâle, Lucerne, and the St. Gothard Tunnel, 842½ M., by the Anglo-Swiss-Gothard-Italian Express daily in 22¾ hrs. Fares as above.

(3) Viâ Calais, Paris, and Lausanne, 806½ M., by the Simplon-Orient Express (train de luxe, supplementary fare payable) daily in 25 hrs. (7l. 6s. 11d.) and the Direct Orient Express in 27 hrs. (fares as above).

(4) Viâ Bologne, Paris, the Mont Cenis Tunnel, and Turin (change), 874 M., by the Rome Express (train de luxe) daily in 27 hrs. (supplementary fare payable). Ordinary fares 7l. 12s. 6d., 5l. 5s. 6d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 13l. 7s. 5d., 9l. 10s. 6d..

(5) Viâ Ostend, Brussels, Strasbourg, Bâle, and Lucerne, 845½ M., daily in 28¾ hrs. Fares 6l. 18s. 2d., 4l. 15s. 4d.

(6) Viâ Dunkirk, Lille, Strasbourg, Bâle (change), and Lucerne, 848 M., daily in 31 hrs. Fares 6l. 8s. 6d., 4l. 4s. 8d., 3l. 2s. 1d.; return-ticket (valid 45 days) 10l. 17s. 3d., 7l. 6s. 0d., 5l. 8s. 4d.

By Air.

The journey from London to Italy may be accomplished by the aeroplanes of the French Air Union as far as Marseilles (viâ Paris and Lyons; daily, except Sun., in 11 hrs., including motor-car journeys; fare 12l. 15s.). There is also a service from Paris to Bâle, Zürich, and Lausanne. Comp. p. xvii.By Sea.

Regular sailings are made by the liners of the under-mentioned companies. The fares average 17-25 l. and the voyage lasts about 8 days. Special tourist fares are offered during the summer, particulars of which may be had on application to the companies (London addresses given below) or to any travel agency (C.I.T., p. xvi; Thos. Cook & Son, Berkeley St., Piccadilly, etc.; American Express Co., 6 Haymarket, S.W. 1; etc.).Orient Line (5 Fenchurch Avenue, E.C. 3) from London to Naples. — Nederland Royal Mail Line (60 Haymarket, S.W. 1) from Southampton to Genoa. — Ellerman's City and Hall Lines (104-106 Leadenhall St., E.C. 3) from Liverpool to Naples. — Nippon Yusen Kaisha (25 Cockspur St., S.W. 1) from London to Naples. — German Africa Service (Greener House, Haymarket, S.W. 1) from Southampton to Genoa.

Looking to Reed's radio plays for some clue, we find a mention of trains to Rome and Naples in the opening of Return to Naples (1950):

Narrator: But that was not yet in Naples, you remember; that was in Rome. That morning, as the train moved South into the early sunlight of the campagna, you had drifted into conversation with an elderly doctor. He invited you to breakfast when you got to Rome. You went. You met his wife. You ate. You drank. And you were told you might stay in their apartment instead of going to a hotel. You accepted. Then you were left to doze off the effects of the journey in the misty heat of the shuttered salone. You slept. You woke. And you saw Alberto for the first time: fat, white-clad, tiptoeing gingerly across the room on his eternal blisters . . . Later that day, he wrote a letter which you were directed to give to his mother in Naples. It began, Carissima Mamma . . .

Alberto: 'Dearest Mamma, This young man, who will present my letter to you, is a very great friend of mine, whom I met this afternoon at the house of Doctor Cappocci . . .'

Narrator: That afternoon you had walked together to the Porta Pia, his small fat hand had created a pool of sweat in the crook of your arm . . .

Alberto: '. . . His name is Enrico. He is English, and is staying with Doctor Cappocci, and next week he is going to Capri. On the way, he will call on you in Naples. Please receive him into our home with the greatest kindness. Your most affectionate Alberto.'

Narrator: That letter, which was never delivered, you kept for many years, together with Alberto's other gifts: the sprig of unpolished coral, the slab of marble pavement from Tarquinia, and the life of Admiral Gravina, which sixteen years later you have yet to read . . .

There was no need to deliver the letter of introduction, for in the end Alberto's father and brother came up to Rome to fetch you, and you all travelled to Naples together.

(faint continental train noises in background)

Alberto: 'Dearest Mamma, This young man, who will present my letter to you, is a very great friend of mine, whom I met this afternoon at the house of Doctor Cappocci . . .'

Narrator: That afternoon you had walked together to the Porta Pia, his small fat hand had created a pool of sweat in the crook of your arm . . .

Alberto: '. . . His name is Enrico. He is English, and is staying with Doctor Cappocci, and next week he is going to Capri. On the way, he will call on you in Naples. Please receive him into our home with the greatest kindness. Your most affectionate Alberto.'

Narrator: That letter, which was never delivered, you kept for many years, together with Alberto's other gifts: the sprig of unpolished coral, the slab of marble pavement from Tarquinia, and the life of Admiral Gravina, which sixteen years later you have yet to read . . .

There was no need to deliver the letter of introduction, for in the end Alberto's father and brother came up to Rome to fetch you, and you all travelled to Naples together.

(faint continental train noises in background)

So, putting two and two together, as it were—if we rely on Reed's autobiographical inspiration for his play—we can place him on the Milan-Naples train through Italy, via Switzerland and France, headed south to Rome, on his way to Naples and the island of Capri. And Reed specifically mentions that his titular "return" to Naples took place two years later, following the Italian conquest of Abyssinia (Ethiopia), so the 1934 and 1936 dates would seem correct. The play places Reed's third visit in 1939, a year before Italy declared war on France and Great Britain. All in all, the "H." in the play visits his adopted Neapolitan family a total of five times, over the course of two decades.