This is repeated in several places, the genesis of which appears to be Reed's obituary in the Times of December 9, 1986:

Called up in 1941, he served—'or rather,' he himself wrote, 'studied'—in the Army, until 1942 when he was seconded to Naval Intelligence at Bletchley. The 'studied' is perhaps explained by the crash-course he underwent in Japanese, and he served out the rest of the war teaching that language to Wrens.

The quotations are from Reed's self-scribed entry for Who's Who. There seemed to be few sources which could illuminate this period in Reed's life, considering the secrecy surrounding the codebreaking efforts at Bletchley Park during the war. Then suddenly, quite recently, there materialized an article in the most unlikely place, Significance, the journal of the Royal Statistical Society: "Edward Simpson: Bayes at Bletchley Park" (June 2010, pp. 76-80), a memoir concerning the implementation of Bayes' Theorem in cracking the Japanese JN-25 and German Enigma codes, by the statistician Edward H. Simpson. "[H]ere, because I know it at first hand," Simpson says, "I describe the use made of Bayes in the cryptanalytic attack on the main Japanese Naval cipher JN 25 in 1943-1945, by the team in Block B which I led." This definitely raised my interest, for we know from the Bletchley Personnel Master List that Reed was assigned to Block B, Naval, for at least part of the war.

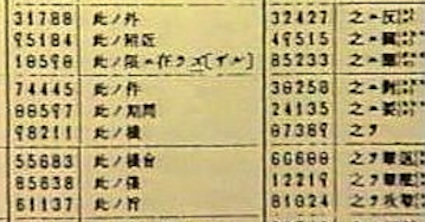

Unlike the German Enigma code, famously enciphered on the eponymous machine, the JN-25 code used by the Japanese Navy utilized a pre-selected vocabulary in printed codebooks, with corresponding values of five-digit numbers to be substituted for the words being transmitted. A bit of tricky addition then took place, resulting in a very secure coded message (albeit with a fatally exploitable flaw).

For an overview of the mathematics Simpson describes being utilized in breaking the Japanese code, you can read John Graham-Cumming's (author of O'Reilly's Geek Atlas) blog post, "Bayes, Bletchley, JN-25 and a 'Modern' Optimization." What grabbed my attention, however, wasn't the inscrutable math, but Simpson's colorful anecdotes of wartime life at Bletchley Park, and the great "diversity of minds" working (and playing) together:

Off-duty we mixed freely. With almost no contact with the people of Bletchley and the surrounding villages, and most of us far from our families, we were a very inward-looking society. All the civilian men (except for some of the most senior) had to serve in the Bletchley Park Company of the Home Guard: this was a great mixer and leveller. On the intellectual side, chess was probably the most glittering circle, with Hugh Alexander, Harry Golombek and Stuart Milner-Barry at its centre...[.] There was music of high quality. Myra Hess visited to give a recital. Performances mounted from within the staff included 'Dido and Aeneas', Brian Augardeís jazz quintet and several satirical revues. A group of us went often by train and bicycle to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon. Scottish country dancing flourished. The Hall, which was built outside the perimeter security fence so that Bletchley people could use it too, provided for dances as well as the performances and a cinema. One memorable occasion was the showing of Munchhausen, in colour (probably the first colour film that most of us had seen) and in German without subtitles. I heard no explanation of how it came to be at Bletchley Park. I doubt that it was through the normal distribution channels.

[p. 79]

Simpson concludes (after much elaboration on letter frequency, probability, alignments, and Bayes factors) with a few reminiscences on where staff went after the war, including:

Henry Reed, a Japanese linguist while in our JN 25 team, went back to poetry, radio plays and the BBC. His 'The Naming of Parts', which has been called 'the best-loved and most anthologised poem of the Second World War', voices his reflections while serving in the Bletchley Park Home Guard.

[p. 80]

How, exactly, did Henry Reed—a Classics scholar fluent in Italian and French, who had taught himself Greek in grammar school—become a linguist on Edward Simpson's Japanese Naval team? Reed had been sent up from the Royal Army Ordnance Corps in 1942, to translate Italian intercepts at Bletchley Park. Following Italy's surrender in September 1943, the bulk of Bletchley's Italian section was absorbed into the Japanese teams. This required that Reed take (or be forcibly given) an intensive, six-month "crash-course" in Japanese. The Japanese course was the brainchild of Col. John Tiltman, who had challenged a retired Naval officer, Capt. Oswald Tuck, to create and head the Bedford Japanese School. Eleven such courses were given in Bedford between 1942 and 1945, beginning in rooms above the Gas Company showroom in Ardor House (under the watchful eye of Mr. Therm), on the corner of The Broadway and Dame Alice Street (opposite the statue of John Bunyan), moved to a house at 7 St. Andrews Road, before finally settling in at 52 De Parys Avenue. Of the 255 students rushed through the school, only nine failed to pass.

Bernard Keefe recollects, in The Emperor's Codes: The Breaking of Japan's Secret Ciphers (Smith, ed., 2001):

The Japanese course was held in a large house in De Parys Avenue, Bedford. We lived in digs. As you entered the house the Japanese course was on the left and a codebreaking course on the right. We knew each other, of course; one of the code-boys was Robert Pitman, a passionate lefty who turned into a right-wing columnist for the Daily Express. But even at that stage it was remarkable that we didn't discuss each other's activities. I was interested in music and had started singing as a baritone at school. Bedford was like musical heaven, because the BBC Symphony Orchestra had been evacuated there, giving broadcasts from Bedford School Hall, or from the Corn Exchange, and added to that were shows by Glenn Miller and his US Army Air Force Band.

[pp. 236-237]

Alan Stripp similarly describes attending the fifth Japanese course—between August, 1943 and February, 1944—in his book, Codebreaker in the Far East (1989):

The course was held in a large room in a detached house in De Parys Avenue, a tree-lined road not far from the town centre. There were about 35 on the course, including two girls, all of us aged about 18 or 19, and most from university Classics courses. We eyed each other sheepishly. We realised later how sensible the intelligence service had been in choosing classicists and a few other dead-language students—for example embryonic theologians working in Aramaic—for these courses in written Japanese, and modem linguists, more accustomed to spoken languages, for spoken Japanese. If the legends are true of chefs being retrained as electricians for the Army, while electricians were turned into chefs, this was no mean achievement.

We had two instructors. The first was Oswald Tuck, a retired naval captain in his sixties, who had been persuaded to teach the first course, starting in February 1942. A bearded, spectacled, quiet and benevolent man, he had taught himself Japanese nearly forty years before, and was now in his element teaching it to others. The other was Eric Ceadel, another classicist and a student on that first course; quick, cool, lucid and methodical. Inevitably he became known as 'Chūi', the Japanese for lieutenant. Later they were helped by David Hawkes.

We worked every weekday, with just enough time at coffee and lunch breaks to prevent our going stale. Most evenings and weekends were needed to learn the language and above all to memorise the characters...[.]

Many of us were music-lovers; I learned much later that chess, crossword puzzles and music had long been considered pointers to a possible proficiency in codebreaking. Several played instruments, and I believe Michael Herzig was the accomplished horn-player whose arpeggios from the Mozart concerto finales often formed fanfares for the start of our classes. We were lucky in having the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Singers evacuated to Bedford and we could often get passes for the orchestral rehearsals; I remember sitting in while Henry Holst was the soloist in the Walton violin concerto, and realising for the first time that if you can sit behind the orchestra you can learn much more than from in front. One evening we persuaded Sir Adrian Boult to give an informal talk about conducting.

We had two instructors. The first was Oswald Tuck, a retired naval captain in his sixties, who had been persuaded to teach the first course, starting in February 1942. A bearded, spectacled, quiet and benevolent man, he had taught himself Japanese nearly forty years before, and was now in his element teaching it to others. The other was Eric Ceadel, another classicist and a student on that first course; quick, cool, lucid and methodical. Inevitably he became known as 'Chūi', the Japanese for lieutenant. Later they were helped by David Hawkes.

We worked every weekday, with just enough time at coffee and lunch breaks to prevent our going stale. Most evenings and weekends were needed to learn the language and above all to memorise the characters...[.]

Many of us were music-lovers; I learned much later that chess, crossword puzzles and music had long been considered pointers to a possible proficiency in codebreaking. Several played instruments, and I believe Michael Herzig was the accomplished horn-player whose arpeggios from the Mozart concerto finales often formed fanfares for the start of our classes. We were lucky in having the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Singers evacuated to Bedford and we could often get passes for the orchestral rehearsals; I remember sitting in while Henry Holst was the soloist in the Walton violin concerto, and realising for the first time that if you can sit behind the orchestra you can learn much more than from in front. One evening we persuaded Sir Adrian Boult to give an informal talk about conducting.

[p. 5]

(He may not have enjoyed quite as much musical entertainment as Keefe and Stripp, if Reed was still billeted in or around Milton Keynes during this time, but we may see evidence of his connections to the BBC, with so much broadcasting from Bedford taking place.)

Stripp also provides an interesting observation in a book co-edited with F.H. Hinsley, Codebreakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park (1993), one of the best resources on British codebreaking during World War II:

A colleague has pointed out that we finished the course with a wide inter-service vocabulary (advance, submarine, aircraft-carrier, independent mixed brigade, commander-in-chief, and the like) but never learnt the Japanese words for 'you' and 'me'. Absurd as this could be for orthodox students, it made good sense for us. Personal pronouns rarely appear in army, navy, or air force signals nor in captured documents, all of which normally take the form of reports, requests, or orders.

[p. 289]

This may provide at least a partial answer as to why there is no evidence of a working knowledge of Japanese in any of Henry Reed's writing: what use is any language to a lyric poet, lacking the words for "you" or "I"?

There still remains the question of the mention in his obituary of Reed having spent the remainder of the war teaching Japanese to members of the Women's Royal Naval Service (Wrens). The urtext, and final word, comes from the most reliable of witnesses: Reed's friend and fellow Brummie, the novelist Walter Allen. In his 1981 autobiography, As I Walked Down New Grub Street, Allen speaks of visiting Reed in Dorset; of Reed working on his life of Hardy—"the life of Hardy"—even as late as 1971; of Reed frequently traveling to London for theatre, opera, and ballet (especially ballet), after the war. Allen begins:

Henry Reed had been demobilised from Intelligence, whither he had been seconded from the Army. Among other things, he had learnt Japanese, which in turn he had taught to Wrens. He intended, he said, to devote every day for the rest of his life to forgetting another word of Japanese.

[p. 149]