|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Guardian"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

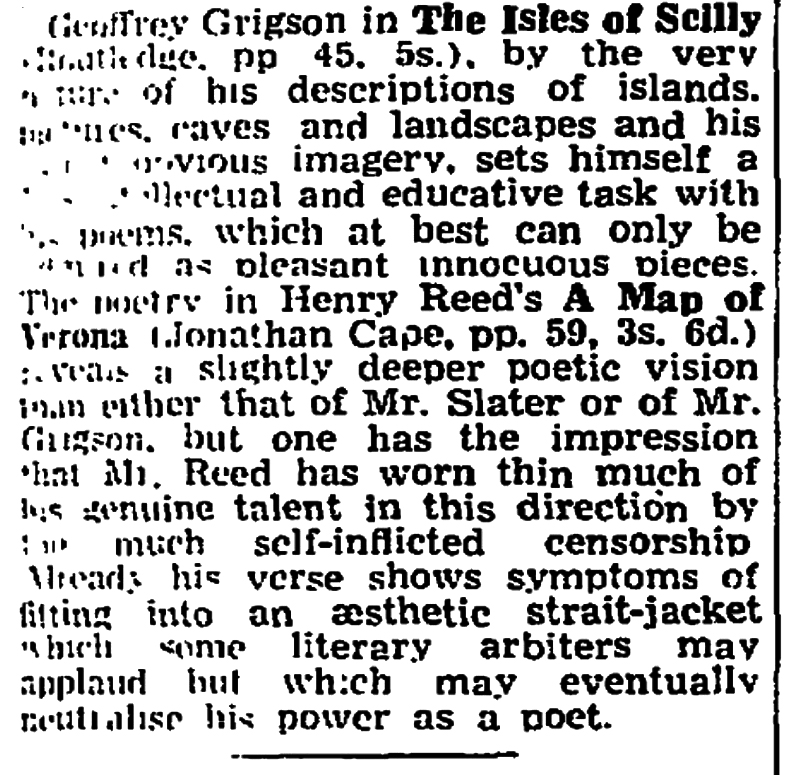

Here is the Guardian's Books of the Day column for July 31, 1946, " Recent Verse." Hugo Manning reviews Talking Bronco by Roy Campbell, The Garden by Vita Sackville-West, Peter Grimes and Other Poems by Montagu Slater, Isles of Scilly by Geoffrey Grigson, and finally A Map of Verona, by Henry Reed.

Manning devotes most of his space to Campbell, whose "inspired invective thunders against many things, including Left-wing poets, Jews, Tartuffes, and even the Beveridge Plan." Manning concludes, however, that "Perhaps Mr. Campbell's muse would become even more considerable if he had fewer bees in his bonnet."

Compared to Talking Bronco, The Garden "seems magnificently serene, and well-disposed to humanity," and acts as "a vehicle for [Sackville-West's] pleasant lyricism, and sustained craftmanship."

Manning has less time and fewer niceties for Slater and Grigson, or for Henry Reed:

The poetry in Henry Reed's A Map of Verona (Jonathan Cape, pp. 59, 3s. 6d.) reveals a slightly deeper poetic vision than either that of Mr. Slater or of Mr. Grigson, but one has the impressions that Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship. Already his verse shows symptoms of fitting into an aesthetic strait-jacket which some literary arbiters may applaud but which may eventually neutralise his power as a poet.

Hugo Manning's career was as eccentric as his reputation. Born in 1913 to Jewish parents, he studied music, but ended up working as a journalist in London and Vienna, and then removed to Buenos Aires in the lead up to the Second World War. He served in North Africa with the British Intelligence Corps, was wounded, and then back in London spent nineteen years on the South American desk for Reuters. His poetry and prose were published privately and by small presses, before his death in 1977. Manning has been described as "a major poet with a minor reputation."

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

My efforts to track the poet Henry Reed through his early decades of the 1930s and 40s are often frustrated by the constant manifestations of another semi-famous "Henry Reed": a popular British band leader who seems to have made nearly daily appearances on the radio during that time. This doppelgänger's career only begins to fade out in the mid- to late-1940s, just as our poet's begins to rise.

It was probably owing to the overwhelming multitude of the Pretender's radio appearances which led me to overlook this article from the Manchester Guardian, in September, 1937: a first-person report—narrative, really—from the annual Piedigrotta music festival in Naples.

For a brief moment I feared it had been written by the musician, but before I even finished the first paragraph I realized it must be the Literary Reed: the ghost of Leopardi materializes; a paraphrase of Baedeker's Italy is inserted; there is a struggle with Italian dialect; Pompeii; and lastly—the clincher—there is a repetition of "to-morrow. To-morrow. To-morrow...".

Reed sounds very close to his subject here. So very close, the music is still ringing in his ears; so I think we shall have to update his timeline/map to include a visit to Naples in the first week of September, 1937:

PIEDIGROTTA

The Piazza di Piedigrotta in Naples is never properly to be called quiet, except occasionally between two and four in the morning. In the first week of September, while people are restlessly waiting for the Popular Song Festival, even this intermission is ignored. On the night of the festival itself one is not especially conscious of enormous noise, for it seems by this time that one has never known silence. Not far away from the radiant tunnel of lights in which the musical competitions take place Virgil lies in his mythical tomb, and in another direction, Leopardi lies in his real one. Do they ever turn in them on this night, one wonders?

The festa once had a ceremony, a ritualistic splendour, but it is not to be supposed that its participants today know that, or bother much about it, though they are happily conscious that their revels are tolerantly presided over by Santa Maria di Piedigrotta in the near-by church. The cook at the pizzeria has never heard of Charles III. The old man who even at this time tries to sell you bootlaces cares nothing for Charles's victory at Velletri in 1744. The tenor who sings the new songs might perhaps be interested to hear that Charles commemorated Velletri by instituting the festival at which he earns whatever he eats instead of bread and butter, but more probably he would merely smile and murmur during the introduction of the second verse that it would have happened anyway. And the information that "this huge fair was held every year with considerable magnificence till the fall of the Bourbon dynasty in 1859" would be greeted with huge derision. Considerable magnificence? Has not M------, the singer, introduced a perfectly splendid and gratuitous high D into the song of the year, a note it was thought would not be heard from a man in our lifetime? Are not the fireworks louder and brighter and longer and cheaper than ever before? Have not more new combinations of instruments been evolved this year than it was ever believed possible? Did you ever think to hear a trumpet and harp duet before? Magnificence?

Every one of us has a Chinese lantern or an impossible nose or a paper hat. We all have those things that you blow out in other people's faces, or those things that you shake round in other people's ears. If you have unlimited money there is unlimited food. Over certain gelaterie there are still old-fashioned flaming gas-jets, but their noise cannot be separately heard as we feverishly lick huge slabs of ice-cream under them. For three singers are I passing in a cart, accompanied by a string octet. To me the words are unintelligible, though I am glad to hear the dialect word "Scetà," which comes in every Neapolitan song, I should think, and means "Wake up." I am deeply impressed and unnecessarily give the waiter a tip. As we hurry away I am severely rebuked for this extravagance by young Neapolitan friends. Arguing furiously, we all step with care over a happily sleeping tramp. I explain that I am not entirely penniless and that it is a season if not of peace on earth at least of goodwill to men. This is considered a silly remark, and after another debate shouted over the noise of bagpipes (bagpipes!) we go on. But the youngest of our party has disappeared. He comes panting up three minutes later, having, by what miracle of cajolery or menace I cannot find out, recovered my penny from the waiter. He gives it to his eldest brother to keep for me.

The tunnel cut through the hill of Posilipo is brightly lit, and one can dance in it, since no automobile will be allowed to pass through it until to-morrow. The wise will have, learned the words and tunes of the songs from the leaflets that have been going about for the last few weeks. Anyone would have taught you the tunes on the violin or the guitar (there is, it appears, no piano in Naples). Then you can join in when the carts containing their little bands come round to catch your approbation.

There is no doubt about which is the best song. Surely a finer librettist than Di Giacomo has arisen in—what is his name, did you say?—the poet who has been so inspired as to mention all the islands in the bay in the same song, and the ghosts of dead lovers at Pompeii as well. And even Tagliaferri could not produce phrases more yielding to the individual choice of vocal ornament than those that M------ is embellishing with his brilliant "mordenti" at the moment. (They say he really comes from Baia, but that is only just round the corner, and it is more than likely that his grandmother came from Naples.)

One must, of course, discriminate with care. The song of the year may be one of those that will not just circle the bay and die after a short excursion to Rome. It may be another "Funiculi, funicula," and go round the world for years and years. But even if nothing historic emerges the individual conscience need not worry. For it will all be a good racket while it lasts. The night will grow louder and louder, and we shall meet more and more new people, who Will remember you because you are English and odd, though you cut them to-morrow.

To-morrow. To-morrow everyone is a bit hoarse. The lights are kept up the next night, for there is a natural attempt to make a good party last as long as it can. But it is rather a hopeless one, and the piazza next day has rather the aspect of an untalking film. In the reaction from the unspeakable recklessness that has led you the night before to embark upon ices, melons of all kinds, lemonade, several "veri vini," and great late figs you have become cowardly, and sit with your companions under the tawny lights of the fountain chewing monkey-nuts. They have forgotten the festa and are reverting to a game of more permanent exhilaration, that of trying to teach you to say "Vedi Napoli e poi muori" in the dialect. "Vega Nabul' u puo' muo'" it sounds like. The last two words are especially hard, and you create much amusement by them.

Henry Reed.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

In 1971, the BBC issued two collections of Henry Reed's plays for radio: Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio, and The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio. The Hilda Tablet volume collects the plays A Very Great Man Indeed (1953); The Private Life of Hilda Tablet (1954); A Hedge, Backwards (1956); and The Primal Scene, As It Were (1958), including restoration of some "indelicate" scenes which had been censored or changed for broadcast.

To mark the publication of the plays, Reed was interviewed by Christopher Ford for an article in the Guardian, " The Reeve's Tale" (Herbert Reeve was the bumbling biographer in the Tablet plays, you see). A retrospective of the plays and their broadcasts, the article features this wonderful photograph of Reed (poorly scanned, sadly), taken by staff photographer Peter Johns:

Reed's quotes for the article amount to just a few paragraphs. Prodded about rumored accusations of libel from (the unnamed) composer Elisabeth Lutyens for his Hilda Tablet character (voiced by Mary O'Farrell), Reed deflects:

As long as the characters are funny it doesn't matter who you're getting at.... In fact I'm not 'getting at' anyone, only myself—there's a good deal of aboriginal Hilda Tablet in me.

The big revelation in the article is that Reed was actually working on an eighth Hilda Tablet script as late as 1968 (in his dedication for Hilda Tablet and Others, Reed says "Altogether, they totalled seven. The number is sometimes given as nine; but people exaggerate"):

I was writing another, it was going to be called 'After a Certain Age'—I was writing it one night and the next morning Douglas Cleverdon, the producer, came round for some other reason and had to break the news that Mary O'Farrell was dead. She was a sine qua non. So it was never completed, but Hilda was going to be the reason why Skalkottas had suppressed his music all his life. We were going to be make out that this was on Hilda's advice.

Mary O'Farrell died on February 10, 1968, more than eight years after the last play in the Hilda Tablet saga, Musique Discrète.

The article closes with a hilarious anecdote of Reed still having trouble coming to terms with his place in the canon of literature and broadcasting, even at the age of 57:

I saw the Penguin Dictionary of Modern Quotations in a shop. I remember thinking 'I've got 150 sleeping tablets at home, and if I'm not in that I'll take some of them with a large Pepsi-Cola.'

Ford reports more than three columns were devoted to Reed in the 1971 edition.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|