Manning devotes most of his space to Campbell, whose "inspired invective thunders against many things, including Left-wing poets, Jews, Tartuffes, and even the Beveridge Plan." Manning concludes, however, that "Perhaps Mr. Campbell's muse would become even more considerable if he had fewer bees in his bonnet."

Compared to Talking Bronco, The Garden "seems magnificently serene, and well-disposed to humanity," and acts as "a vehicle for [Sackville-West's] pleasant lyricism, and sustained craftmanship."

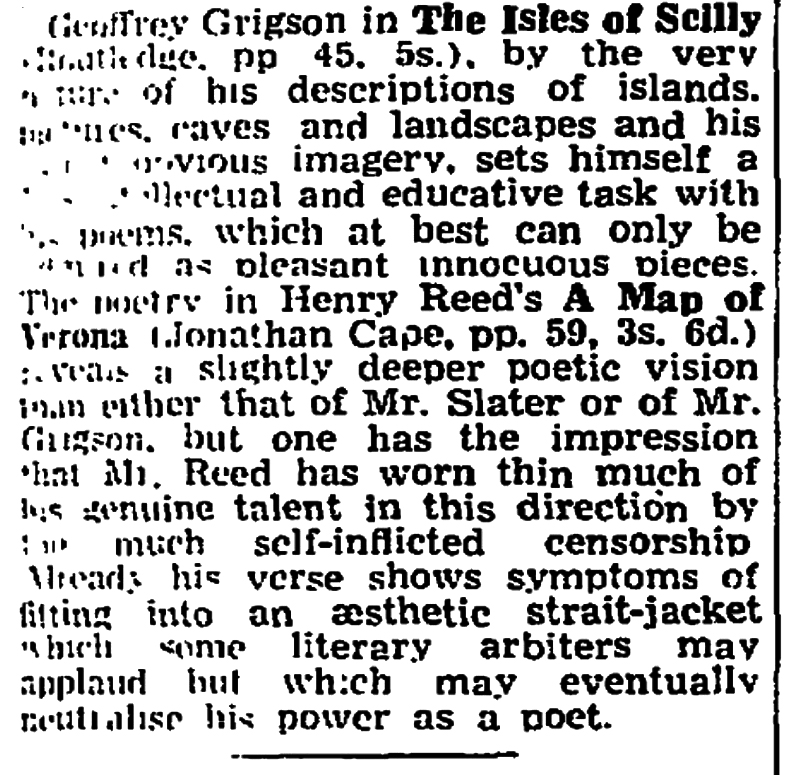

Manning has less time and fewer niceties for Slater and Grigson, or for Henry Reed:

The poetry in Henry Reed's A Map of Verona (Jonathan Cape, pp. 59, 3s. 6d.) reveals a slightly deeper poetic vision than either that of Mr. Slater or of Mr. Grigson, but one has the impressions that Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship. Already his verse shows symptoms of fitting into an aesthetic strait-jacket which some literary arbiters may applaud but which may eventually neutralise his power as a poet.

Hugo Manning's career was as eccentric as his reputation. Born in 1913 to Jewish parents, he studied music, but ended up working as a journalist in London and Vienna, and then removed to Buenos Aires in the lead up to the Second World War. He served in North Africa with the British Intelligence Corps, was wounded, and then back in London spent nineteen years on the South American desk for Reuters. His poetry and prose were published privately and by small presses, before his death in 1977. Manning has been described as "a major poet with a minor reputation."