|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Newspapers"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

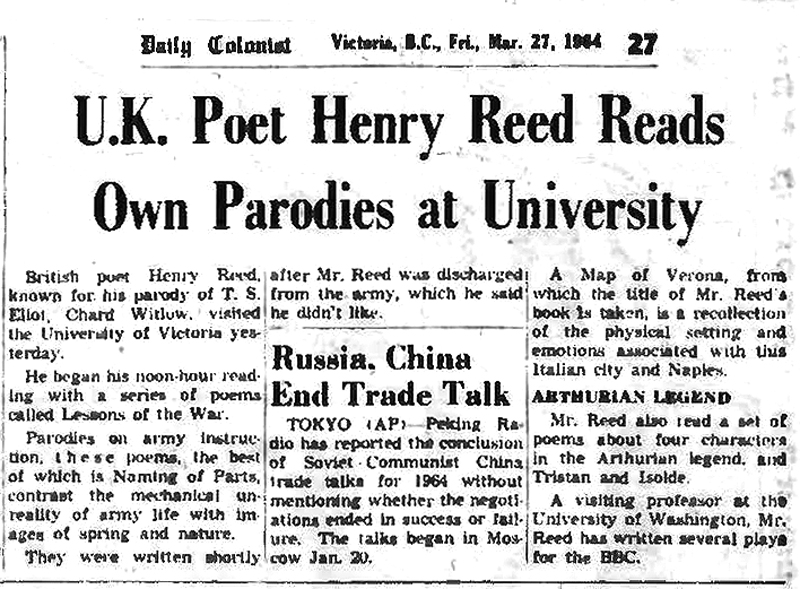

What a treat to be able to add another country to the list of places Henry Reed visited! The Daily Colonist of Victoria, British Columbia reports that Reed gave a noontime poetry reading at the University of Victoria on Thursday, March 26, 1964. Reed may have gone at the invitation of Robin Skelton.

Reed was a Visiting Professor of English at the University of Washington, Seattle at the time, a guest position opened up by the untimely death of Theodore Roethke. So he just popped over to Canada for a reading:

U.K. Poet Henry Reed Reads

Own Parodies at University British poet Henry Reed, known for his parody of T. S. Eliot, Chard Witlow [sic], visited the University of Victoria yesterday.

He began his noon-hour reading with a series of poems called Lessons of the War.

Parodies on army instruction, these poems, the best of which is Naming of Parts, contrast the mechanical unreality of army life with images of spring and nature.

They were written shortly after Mr. Reed was discharged from the army, which he said he didn't like.

A Map of Verona, from which the title of Mr. Reed's book is taken, is a recollection lot the physical setting and emotions associated with this Italian city and Naples.

ARTHURIAN LEGEND

Mr. Reed also read a set of poems about four characters in the Arthurian legend, and Tristan and Isolde.

A visiting professor at the University of Washington, Mr. Reed has written several plays for the BBC. "Several" plays for the BBC. By my count, Reed wrote or translated 36 radio plays before 1964.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

M.L. Rosenthal was an American contemporary of Henry Reed, born in 1917 in Washington, D.C., he taught at New York University for more than 50 years. Rosenthal was a poet, editor, and critic, and is credited with attributing "confessional" to the Confessional Poetry movement.

An early review by Rosenthal, " Experience and Poetry," appears in the New York Herald Tribune for October 17, 1948: Rosenthal reviews Henry Reed, Laurie Lee's The Sun My Monument, E.J. Pratt's Behind the Log, Louis O. Coxe's The Sea Faring, Robert McKinney's Hymn to Wreckage, and Four Poems by Rimbaud, translated by Ben Belitt.

Experience and Poetry A MAP OF VERONA AND OTHER POEMS.

By Henry Reed. . . . 92 pp. . . . .

New York: Reynal and Hitchcock. . . . $2.50.

Reviewed by M. L. Rosenthal

HENRY REED shares with Laurie Lee, another young English "war poet," a kind of hurt pacifism and the familiar irony that sell so cheaply of late. They share, too, in that unhappy vice of young intellectuals—a certain blandness of which the ever-simple irony is a symptom and which allows them, at a moment's notice, to discuss everything as though it were nothing and vice versa. But Reed has the more inclusive sensibility, and he has been able to protect it by skills of craft, fashioning an armor of rhythmic, stanzaic, and musical structure. Despite their common conviction that the world is flat, Reed has written more verse in the rich "lyric-contemplative" mode and has used mythological themes from Homer to Melville to help him get his bearings. He is further into his art: such places as "Judging Distances," "Sailor's Harbor," and the title-poem achieve something fine and honest, with a dramatic tension that resolves itself by a narrowing of focus from general to intimate personal awareness: "reversal" with the true tragic shock of painful realization. Rosenthal published two popular poetry books in 1967: a book of criticism, The New Poets: American and British Poetry since World War II (London: Oxford University Press); and and anthology, The New Modern Poetry; British and American Poetry since World War II (New York, Macmillan). As far as I can tell, however, Reed doesn't appear in either.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

In 1950 and 1951, there was a series of broadcasts on the BBC's Home Service, produced by Brandon Acton-Bond, wherein three travellers would make the same journey separately, and record their impressions.

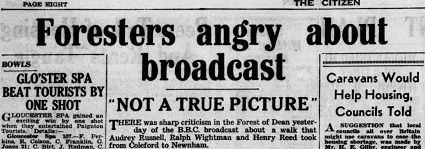

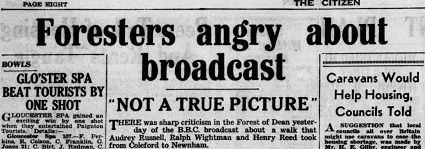

There were four programs, in all: " Pictures of a Road: Coleford to Newnham through the Forest of Dean" (June, 1950, with Audrey Russell, Henry Reed, and Ralph Wightman); " Pictures of a River: The Dart from Dartmouth to Totnes" (August, 1950, William Aspden, Georgie Henschel, and Johnny Morris); " Pictures of a Railway Journey: Plymouth to Princetown" (May, 1951, Georgie Henschel, Ralph Wightman, and Johnny Morris); and " Pictures of a Ferry-Boat Journey: Lymington to Yarmouth (Isle of Wight)" (June, 1951, Audrey Russell, Charles Causley, and Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald).

The first program, broadcast on Sunday, June 18, 1950, was apparently not well-received by the locals. It featured Audrey Russell, Ralph Wightman, and Henry Reed walking through the Forest of Dean from Coleford to Newnham, and resulted in this criticism of their reporting in the Gloucester Citizen for June 22, 1950:

Foresters angry about broadcast

"NOT A TRUE PICTURE"

THERE was sharp criticism in the Forest of Dean yesterday of the B.B.C. broadcast about a walk that Audrey Russell, Ralph Wightman and Henry Reed took from Coleford to Newnham.

"If the purpose of the broadcast was to convey a true picture of the district they traversed," said the vicar of St. Stephen's, Cinderford (the Rev. D .R Griffiths) in an interview, "then the descriptions given were very unfiar and misleading."Henry Reed said that when he got into sight of Cinderford he found stretching out in front of him for miles a place of 'grey and pink hideousness.' We can allow poets to indulge in any amount of license, but to use 'hideous' as a term of Cinderford is an exaggeration. "Ralph Wightman said that St. Stephen's Church is just as 'Victorian and ugly as the huge chapels in the main street! Mr. Wightman doubtless knows a lot about pigs, poultry and sheep, but we cannot take his judgment on church architecture as possessing any value. The church was built just over 60 years ago, designed by a fine architect named Lingen Barker. The design was approved by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners Building Board of that time which had a panel of 13 architects. St. Stephen's church cannot be described as beautiful, but it is not ugly."

Said Henry Reed of Coleford "I didn't think Coleford had looked after itself very well. The cottages on its outskirts were horribly dilapidated; its church tower had no church; the little Town Hall, with its blue egg cosy on top, was one of the oddest buildings I've ever seen. I was only persuaded that it WAS the Town Hall by the backs of five uncomfortable-looking chairs in a first floor bow window."

Audrey Russell noticed that when the town clock struck the hour the hands were two minutes to.Said Mr. C. E. Gillo (chairman of the Coleford Parish Council): "The Forest of Dean has suffered at the hand of the B.B.C. I am tired of people coming here and running down the place. We are painfully aware of the lack of amenities and the ugly blots, but the Forest of Dean has suffered years of industrial depression and was often governed by men with a retarded outlook. "We are now trying to catch up on what we have lost. We are not helped by those who come here and condemn. It is grossly unfair to be measured by what might be called the municipal yardstick."

Imagine my delight, when perusing the travelled route through Google Street View, to find that Coleford's church tower still has no church.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

My efforts to track the poet Henry Reed through his early decades of the 1930s and 40s are often frustrated by the constant manifestations of another semi-famous "Henry Reed": a popular British band leader who seems to have made nearly daily appearances on the radio during that time. This doppelgänger's career only begins to fade out in the mid- to late-1940s, just as our poet's begins to rise.

It was probably owing to the overwhelming multitude of the Pretender's radio appearances which led me to overlook this article from the Manchester Guardian, in September, 1937: a first-person report—narrative, really—from the annual Piedigrotta music festival in Naples.

For a brief moment I feared it had been written by the musician, but before I even finished the first paragraph I realized it must be the Literary Reed: the ghost of Leopardi materializes; a paraphrase of Baedeker's Italy is inserted; there is a struggle with Italian dialect; Pompeii; and lastly—the clincher—there is a repetition of "to-morrow. To-morrow. To-morrow...".

Reed sounds very close to his subject here. So very close, the music is still ringing in his ears; so I think we shall have to update his timeline/map to include a visit to Naples in the first week of September, 1937:

PIEDIGROTTA

The Piazza di Piedigrotta in Naples is never properly to be called quiet, except occasionally between two and four in the morning. In the first week of September, while people are restlessly waiting for the Popular Song Festival, even this intermission is ignored. On the night of the festival itself one is not especially conscious of enormous noise, for it seems by this time that one has never known silence. Not far away from the radiant tunnel of lights in which the musical competitions take place Virgil lies in his mythical tomb, and in another direction, Leopardi lies in his real one. Do they ever turn in them on this night, one wonders?

The festa once had a ceremony, a ritualistic splendour, but it is not to be supposed that its participants today know that, or bother much about it, though they are happily conscious that their revels are tolerantly presided over by Santa Maria di Piedigrotta in the near-by church. The cook at the pizzeria has never heard of Charles III. The old man who even at this time tries to sell you bootlaces cares nothing for Charles's victory at Velletri in 1744. The tenor who sings the new songs might perhaps be interested to hear that Charles commemorated Velletri by instituting the festival at which he earns whatever he eats instead of bread and butter, but more probably he would merely smile and murmur during the introduction of the second verse that it would have happened anyway. And the information that "this huge fair was held every year with considerable magnificence till the fall of the Bourbon dynasty in 1859" would be greeted with huge derision. Considerable magnificence? Has not M------, the singer, introduced a perfectly splendid and gratuitous high D into the song of the year, a note it was thought would not be heard from a man in our lifetime? Are not the fireworks louder and brighter and longer and cheaper than ever before? Have not more new combinations of instruments been evolved this year than it was ever believed possible? Did you ever think to hear a trumpet and harp duet before? Magnificence?

Every one of us has a Chinese lantern or an impossible nose or a paper hat. We all have those things that you blow out in other people's faces, or those things that you shake round in other people's ears. If you have unlimited money there is unlimited food. Over certain gelaterie there are still old-fashioned flaming gas-jets, but their noise cannot be separately heard as we feverishly lick huge slabs of ice-cream under them. For three singers are I passing in a cart, accompanied by a string octet. To me the words are unintelligible, though I am glad to hear the dialect word "Scetà," which comes in every Neapolitan song, I should think, and means "Wake up." I am deeply impressed and unnecessarily give the waiter a tip. As we hurry away I am severely rebuked for this extravagance by young Neapolitan friends. Arguing furiously, we all step with care over a happily sleeping tramp. I explain that I am not entirely penniless and that it is a season if not of peace on earth at least of goodwill to men. This is considered a silly remark, and after another debate shouted over the noise of bagpipes (bagpipes!) we go on. But the youngest of our party has disappeared. He comes panting up three minutes later, having, by what miracle of cajolery or menace I cannot find out, recovered my penny from the waiter. He gives it to his eldest brother to keep for me.

The tunnel cut through the hill of Posilipo is brightly lit, and one can dance in it, since no automobile will be allowed to pass through it until to-morrow. The wise will have, learned the words and tunes of the songs from the leaflets that have been going about for the last few weeks. Anyone would have taught you the tunes on the violin or the guitar (there is, it appears, no piano in Naples). Then you can join in when the carts containing their little bands come round to catch your approbation.

There is no doubt about which is the best song. Surely a finer librettist than Di Giacomo has arisen in—what is his name, did you say?—the poet who has been so inspired as to mention all the islands in the bay in the same song, and the ghosts of dead lovers at Pompeii as well. And even Tagliaferri could not produce phrases more yielding to the individual choice of vocal ornament than those that M------ is embellishing with his brilliant "mordenti" at the moment. (They say he really comes from Baia, but that is only just round the corner, and it is more than likely that his grandmother came from Naples.)

One must, of course, discriminate with care. The song of the year may be one of those that will not just circle the bay and die after a short excursion to Rome. It may be another "Funiculi, funicula," and go round the world for years and years. But even if nothing historic emerges the individual conscience need not worry. For it will all be a good racket while it lasts. The night will grow louder and louder, and we shall meet more and more new people, who Will remember you because you are English and odd, though you cut them to-morrow.

To-morrow. To-morrow everyone is a bit hoarse. The lights are kept up the next night, for there is a natural attempt to make a good party last as long as it can. But it is rather a hopeless one, and the piazza next day has rather the aspect of an untalking film. In the reaction from the unspeakable recklessness that has led you the night before to embark upon ices, melons of all kinds, lemonade, several "veri vini," and great late figs you have become cowardly, and sit with your companions under the tawny lights of the fountain chewing monkey-nuts. They have forgotten the festa and are reverting to a game of more permanent exhilaration, that of trying to teach you to say "Vedi Napoli e poi muori" in the dialect. "Vega Nabul' u puo' muo'" it sounds like. The last two words are especially hard, and you create much amusement by them.

Henry Reed.

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

In the 1950s, Joan Newton was the radio and television reviewer for the Catholic Herald. Through the magic of the paper's online archive, it's possible to trace Ms. Newton's love affair with Henry Reed's Hilda Tablet plays on the BBC's Third Programme, starting with A Very Great Man Indeed in 1953:

Somebody's guardian angel—mine, I suppose—suggested to me to listen to Henry Reed's "A Very Great Man Indeed," produced by Douglas Cleverdon on the Third. Just before, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra from Edinburgh had been coming through very badly and I was prepared to have to turn off the play as well. I'm glad I didn't.

It was about "the late Richard Shewin, 'the poets' novelist,'" and his biographer, Herbert Reeve (Hugh Burden), was visiting the great man's relations and friends to get an idea of his character.

"Dear me, I've never heard of Richard Shewin," I was thinking as I listened to the beginning. But when the earnest biographer got upstairs to see the permanently bedded brother of the late R.S., and after meeting with the sister-in-law and her cats, I realised that either it was meant to be funny or something had gone wrong somewhere. And funnier and funnier it grew, and more and more enjoyable.

I find it hard to decide which incident I enjoyed most—Mary O'Farrell as the composeress, Norman Shelley being a contemporary novelist, Harry Hutchinson as the Irish poet, or the glorious ending with the late novelist's nephews singing "Don't Hurt My Heart," a very tearful lyric in the Frankie Laine manner. Repeat, please.

This loss in a few days of almost all the family's chief stand-bys for lighter listening [ Take it from Here, Life with the Lyons, Talk about Jones, and Have a Go] was made bearable only by the further repeat of the Third Programme's "A Very Great Man Indeed," written by Henry Reed and produced by Douglas Cleverdon. I had heard this twice before, but laughed as much as ever.

The only jarring note for me was the Graham Greeneish episode about the worried priest at the end, which was an accurate pardoy in style only and not in content, and had too much the air of mischievous afterthought to make an artistic conclusion.

I wonder if the author and producer—and perhaps more especially, the composer, Donald Swann—will be able to repeat their success in " The Private Life of Hilda Tablet," promised us for May 24 and 26. Those who did not hear "A Very Great Man" may like to know that Hilda is a modern composer. They ought to be warned, too, that the play is unlikely to be wholly suitable for children. Perhaps it was rather much to expect that Henry Reed should hit the bell so definitely with his "Private Life of Hilda Tablet" (Third Programme) as he did with "A Very Great Man Indeed." All the same, it was a splendid entertainment and one still clamours for more of the same kind.

The defects in this second show—they are defects in comparison only—seemed to me to be that the characters had become more familiarly "types" than they were before, that the satire was slightly less sharp, and that some episodes, such as the "drunk" scene at Hilda's school, were rather too drawn out.

Mary O'Farrell as Hilda, the modern composeress, was as hearty and vigorous as ever but not quite as real as before—less Waugh and more Wodehouse. Herbert Reeve, the scholar through whose reminiscences we become acquainted with all these odd people, was still a deliciously wide-eyed and dedicated Boswell; but in the earlier show his approach was more "dead-pan," more Third Programme, and consequently he came out more amusingly in contrast with the astonishing goings-on in which he gets himself involved.

I hope we shall have more of one gorgeous new character, Deryck Guyler as the Rector of Mull Extrinseca.

Donald Swann's clever musical parodies, which naturally had more scope this time, lived up to all expectations. And that brings me on to the unhappy case of Marjorie Westbury, who was so impressive as Elsa Strauss, Hilda's long-suffering singer—'Throw yourself at the note if you like, but for heaven's sake don't hit it!'—that I am now quite unable to think of her as anything else.

This week they [ Said the Cat to the Dog] were assisted by "Mrs. Kerry," a cow, but she is, perhaps, a bit too much of a chatterbox and just a weeny bit too "Oirish" for our liking. I mention her specially because she is played by another of those versatile radio actresses, Mary O'Farrell. It's a far cry from her acting a cow to being the energetic Hilda Tablet in the latest of Henry Reed's witty Third Programme diversions, " Emily Butter."

I was looking forward to hearing Hilda's much-publicised opera. Unfortunately, a slight indisposition prevented me, and I only hope that there will soon be a repeat. In all my years of radio listening I have yet to find purer gold than in the Third Programme's set of plays by Henry Reed about the mythical author Richard Shewin. A few weeks ago we had a repeat of the first play, "A Very Great Man Indeed." I do not usually like hearing a play twice, but this I have heard four or five times and have experienced the same delight each time.

At the end of February, " A Hedge Backwards," which is meant to be a final digression on the subject, gave us nearly as much pleasure. Hugh Burden, as the innocent and revering biographer, is perfect and as sordid fact after sordid fact about the "great" author is brought to light our enjoyment increases with his bewilderment. The musical satires by Donald Swann are also perfect and if you have never listened to these plays you must certainly look out for any repeats. Last Friday, too, on the Third, I heard again the third of the wonderful trilogy about the works of the fabulous Richard Shewin and Hilda Tablet—this being "A Hedge Backwards." I hope these three plays will be offered to us again and again for many years to come.

The only fault I found with this collection [ From the Third Programme: A Ten Years' Anthology] was that it had not included some of the lyrics, at least, from Henry Reed's masterpieces, "A Very Great Man Indeed" and "Through a Hedge Backwards" [ sic]. This is a strictly personal grouse because the editor has included Reed's more serious "Antigone" in this anthology. Thursday was, in fact, a happy day on the radio for everyone, for in the evening we heard again the first of Henry Reed's saga about literary people "A Very Great Man Indeed." I have praised this work and its sequels so often that I am afraid of being accused of some queer kind of fixation.

My favorite bit: '[U]nlikely to be wholly suitable for children.'

Hilda Tablet is 60 years old this year, and 2014 will be the centenary of Henry Reed's birth. Repeat, please.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

A review of the American edition of Reed's A Map of Verona and Other Poems appears in a most unlikely place: the Delta Democrat-Times of Greenville, Mississippi, from October 12, 1947. Doubly unusual because the book was only just published on October 8th, so the reviewer must have received an advanced copy. Greenville, I was quick to discover, has a vast and rich literary pedigree, and produced nearly one hundred published writers in the 20th century.

Doris Karsell (1922-2010), was a Denver artist and muralist, educated at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center. She lived and worked in Greenville while her husband was managing editor at the Delta Democrat-Times (owned by Pulitzer Prize winner Hodding Carter), setting up a studio with the illustrator Elizabeth Calvert and advertising personalized book plates, portraits, and murals. Apparently, Doris was affectionately known as "Dodo". You can see a free preview of her review, " New Poet Now Mature," on NewspaperARCHIVE.com:

Karsell begins by chiding another reviewer ( Walter Allen?) for attempting to place Reed outside or above the rest of the Eliot-imitating oeuvre ("It is an act of great inaccuracy to preclude"), and then rules the book "the exception and the good." She admires Reed's style, finding "each line in the collection has been cut and finished with precision. One believes that no other form or words could have been used." She discovers a strange kinship with the poet:

As if the words were sent to the receiving system by strings, and breath through hollowed wood, one is made to climb out of the box of his own limitations. One is given the long ribbon of time in its three phases. It is a clever thing that the beginning sketch establishes partnership. For the reader knows he himself has written the first verse which Henry Reed has borrowed. He knows that he is the sole one to experience it.

Most of the rest of the review is pedestrian walking-tour stuff, going through the book chapter-by-chapter, like describing rooms to a houseguest. But Karsell concludes strongly, advising, "Read the whole volume aloud, even should you read it alone," and then finally, prophetically: "It is possible we shall remember Henry Reed."

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|