One of my favorite pieces on Henry Reed is this 1971 retrospective from the Guardian, "The Reeve's Tale," by the music critic Christopher Ford. It was a promotional piece written for the publication of Reed's two collections of radio plays, The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio, and Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (London: British Broadcasting Corporation). From this article we also get not one (Manchester edition), but two photographs of Reed, (London edition, shown here) taken by Peter Johns (previously).

In the article's closing paragraph, Reed says, "I saw the Penguin Dictionary of Modern Quotations in a shop. I remember thinking 'I've got 150 sleeping tablets at home, and if I'm not in that I'll take some of them with a large Pepsi-Cola'."

Ford reports that Reed's quotes take up "more than three columns, the entries mostly coming from the Tablet plays."

It's difficult to express what an achievement this amount of textblock is, appearing in this small Penguin paperback: Reed gets more than a page and a half of space devoted to his poems and plays. He actually appears on the same page with the poet and critic he is famously often confused with, Herbert Read. Read gets only one quote (and surprise! It's not "To a Conscript of 1940"):

Looking to Reed's peers, we find that even W.H. Auden receives only two columns; T.S. Eliot gets two and a half; Louis MacNeice gets one column: half a page. Stephen Spender, barely half a column. Stevie Smith gets five quotes. C. Day Lewis? Four. George Orwell gets three, three and a half columns? A little more. W. Somerset Maugham gets three columns. I mean, Evelyn Waugh rates three columns. This is what I'm saying.

I think the superabundance of Henry Reed in this curious volume is owed to two things: firstly, the entire Hilda Tablet sequence was replayed on the new BBC Radio 3 between December, 1968 and January 1970. ("Altogether, they totalled seven. The number is sometimes given as nine; but people exaggerate.") These repeats were in tribute to the incomparable radio actress Mary O'Farrell, who had died on February 10, 1968. Reed hosted (and Douglas Cleverdon produced) a program of recollections and recordings for O'Farrell in January, 1969. Dame Hilda died with O'Farrell, and a planned eighth installment for the radio was abandoned.

Secondly, this largess must be credited (or blamed) on the editors, J.M. Cohen and his son, M.J. Cohen. I suspect the elder Cohen knew Reed's work not just from the radio, but from earlier anthologies for Penguin: The Penguin Book of Comic and Curious Verse (1952), More Comic and Curious Verse (1956), and Yet More Comic and Curious Verse (1959).

I'll use the Cohens' book to expand my rather meager "Henry Reed quotes" page.

|

Penguin Quotes

Terence, This Is Stupid S**tHere's a goodie found in Google Book Search: from a double-issue of the Harvard Advocate from 1975 devoted to W.H Auden:

I learned from him [Auden] the parody of A.E. Housman, attributed, whether correctly or not, to Henry Reed, which goes: The cow lets fall at evening(Harvard Advocate 108, nos. 2-3 [1975]: 49.) A parody of Housman's "Terence, This Is Stupid Stuff." Here's the issue as seen in Google Book Search: W.H. Auden, 1907-1973. It contains reminiscences by a whole generation of poets influenced by Auden: Randall Jarrell, Richard Eberhart, Karl Shapiro, William Empson, C. Day Lewis, Elizabeth Bishop, Tennessee Williams, and Stephen Spender, among others. Unfortunately, and as is often the case, Google only allows "snippet" views of the text, and I have no idea who's the author of this particular article. (Quick! Run to your local university library and scrounge me up a copy!) We'll assume, for now, that the attribution is likely incorrect, and assume that it was either Auden himself, or even Sir Herbert Read parodying Housman.

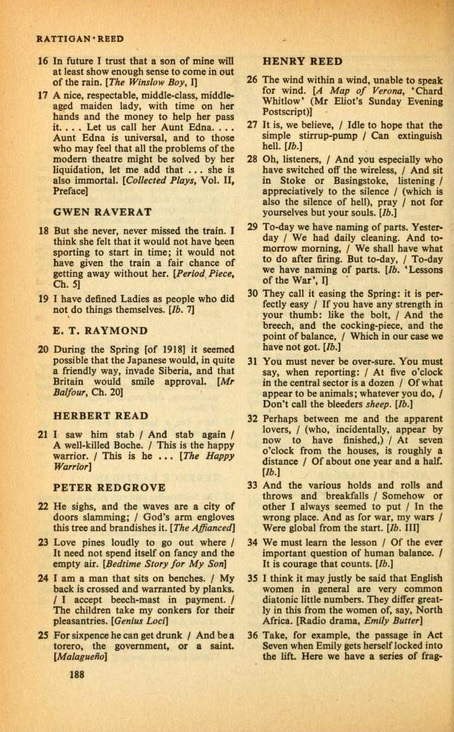

Escaping the Sin of BroadnessLast September, I complained of not being able to find the source of an oft-quoted comment by T.S. Eliot, who remarked that Reed's poem, "Chard Whitlow," was the only parody deserving of its success. Realizing that I have been less than devoted to updating here, and that I have been stockpiling items worthy of posting, let us begin at the top of the pile: Dwight Macdonald's (Wikipedia) Parodies: An Anthology from Chaucer to Beerbohm—and After (WorldCat).

Here, it seems, is the original source (.pdf) of Eliot's comment: This famous parody was originally an entry in a New Statesman contest. 'Most parodies of one's own work strike one as very poor,' Mr. Eliot writes. 'In fact one is apt to think one could parody oneself much better. (As a matter of fact some critics have said that I have done so.) But there is one which deserves the success it has had, Henry Reed's Chard Whitlow.' Broadness is the sin of most Eliot parodies; Mr. Reed's alone seems to me to escape it. The one following, by 'Myra Buttle,' who is a Cambridge don, does not. I have included it because it is funny and because I thought some sample of The Sweeniad should be given. (I apologize for the lousy scan from Parodies. I need to report that misbehaving copier to the library staff.) Alas, Mr. Macdonald does not credit or cite the source of his 'Mr. Eliot writes'. As an editor of The Partisan Review, he did have reason to correspond with Eliot, and letters from Eliot in Macdonald's papers do appear from the right time period: 1959-1960 (see the "Guide to the Dwight Macdonald Papers," 230 page .pdf, from the Manuscripts and Archives department at Yale University Library). Macdonald is careful to include permissions for using other quoted material in his text, but none is provided for Eliot. Did he write Eliot and ask the poet's opinion of his parodists? Is Eliot's letter residing in some box at Yale?

The Cat and the FiddleAlmost two years ago, I was trying to settle the source of a strange quote attributed to a "Sir Henry Reed," regarding the nursery rhyme, "Hey Diddle Diddle." The quote, which appeared in two journal articles about Mother Goose, is as follows: 'I prefer to think that it commemorates the athletic lunacy to which the strange conspiracy of the cat and the fiddle incited the cow.'

I finally tracked down the original source of this quotation in vol. 117 of the series Children's Literature Review (Tom Burns, ed. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2006. p. 60), which reprints a 1955 review by Clifton Fadiman of The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, edited by Iona and Peter Opie (1952). Going to the Opie's text, I discover that the Children's Literature Review misprints the attribution as "Sir Henry Reed." The 1952 and 1997 editions of the Oxford volume (which are identical in this section) have 'The sanest observation on this rhyme seems to have been made by Sir Henry Reid'. The double error of including the honorific "Sir" and the misspelling "Reid" leaves me to believe this is probably not our Henry. It seems more likely attributable to Sir Herbert Read, or to another Sir, altogether. And, actually, since Read wasn't knighted until 1953 and the Oxford edition was published in 1952, we are probably looking for some witty 19th century gentleman. This was made possible using Gale's Literature Criticism Online, a database which provides access to ten collections of literary criticism, including Contemporary Literary Criticism, Poetry Criticism, and Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism, as well as Children's Literature Review. Access to Gale's databases is provided by many public and university libraries.

Unattributed EliotThe Rt Hon. Kenneth Baker, in his excellent anthology Unauthorized Versions: Poems and Their Parodies (OCLC WorldCat), assiduously includes this explanatory note with Henry Reed's famous send-up of Eliot's Four Quartets:

This parody by a poet celebrated in his own right won a competition in the New Statesman. Eliot himself commented: 'In fact one is apt to think one could parody oneself much better. (As a matter of fact some critics have said that I have done so.) But there is one which deserves the success it has had, Henry Reed's "Chard Whitlow".' There is no single poem to put beside Reed's parody, which cleverly manages to summon echoes from almost all Eliot's work, but a few examples are given here. Lord Baker places "Chard Whitlow" side-by-side with lines from Eliot's "Little Gidding," "Gerontion," "Ash Wednesday," and "Choruses from 'The Rock'." It seems unlikely (if not impossible) that Reed was parodying "Little Gidding," since that poem was written in 1942, after the publication of "Chard Whitlow" (.pdf). It's more likely Reed had in mind the earlier verse of Eliot's Four Quartets, such as "Burnt Norton" (1935). The possibility exists, therefore, that Reed's poem actually influenced Eliot's. Stephen Spender, however, in his book T.S. Eliot (New York: Viking, 1975), says that Eliot, in fact, 'relished' the parody, but that he was not seeking to 'emulate' it (p. 177). Regardless of who influenced whom, the real mystery is the source of Eliot's admiration of "Chard Whitlow," quoted above. Baker's anthology includes acknowledgments for the poems he has compiled, but I'm fairly certain there is no attribution for Eliot's words, and no footnotes accompany the explanatory notes. Does anyone have a copy they can double-check for me? The quote appears in numerous places on the web (including Robert Pinsky's article for Slate magazine), but always lifted from Baker's anthology, it would seem. Where did Baker take Eliot's quote from? What is the original source? Incidentally, for his winning poem in the New Statesman's parody contest, Reed was awarded "the usual prize" of two Guineas (42 shillings).

Mystery SolvedWell, the mystery is solved, and the fault is mine. It's all right here, in black and white.

See, here's the story: I couldn't figure out where Reed had written the line 'To fight without hope is to fight without grace.' The quote opens the chapter "Where Are the War Poets?" in Shires' British Poetry of the Second World War. I did find, however, a similar line in the poem, "To a Conscript of 1940": 'To fight without hope is to fight with grace.' Going back to my original photocopy this evening, I realized I had copied the quote incorrectly, inserting the second without. By doing so, I fell victim to one of the classic blunders. I mistook Herbert Read for Henry Reed. God help me. The correct quote is 'To fight without hope is to fight with grace.' Shires misattributed it to Reed; I failed to copy it correctly; and now I have sorely embarrassed myself by not recognizing the compounding error, despite having the source material in front of me! For shame!

For Lack of ElizabethI reached a minor milestone this past weekend: I closeted myself in the library, and labeled and stuffed nearly 150 manila envelopes with the last of the photocopies from the original plastic filebox, as well as most of the printouts and copies I've made since making the decision to go Noguchi. Now, all I need to do is spend four or five hours double-checking that all the items in these envelopes are actually in the bibliography, and then I can file them in the bookcase. Progress! The tide is turning.

But no matter how much I file away, new items are still emerging, including this fascinating item. In Victoria Glendenning's biography of Elizabeth Bowen (New York: Knopf, 1978), there is this possibly scandalous revelation: As to reviewing, which she always did a great deal of, she was ambivalent. She was a notoriously kind reviewer of novels; she preferred not to write about a book she could not praise, and was known in the business as a very soft touch. But "it is a perfectly awful business", she wrote to Virginia Woolf about The New Statesman fiction-reviewing stint she was doing in 1935, alternating weekly with Peter Quennell. Once when Henry Reed was staying at Bowen's Court and she was very involved with her own work, "Henry even did some of my Tatler reviews for me, which left me more time for the novel: a friendly act". It was indeed. (p. 146.) I was flabbergasted. I read it again: Henry Reed wrote some of Elizabeth Bowen's book reviews for her. Elizabeth Bowen began writing for The Tatler in 1938. In 1940 the journal merged to become the monthly Tatler & Bystander, and from 1945 to 1958 Bowen was reviewing fiction regularly, in her "Book Shelf" column. Stallworthy mentions that Reed spent a fortnight holiday in April, 1946 at Bowen's Court, Elizabeth's ancestral summer home in County Cork, Ireland. Would this be the visit when he did her Tatler reviews for her? Which novel was she working on? Was it The Heat of the Day, her only work of long fiction published between 1938 and 1949? Also, the quote about Reed is apparently unattributed: it can't be part of the preceding letter to Virginia Woolf, because Woolf committed suicide in 1941. I am at an impasse, however, because there is no run of 1940s Tatler & Bystander even remotely accessible, and there is no available index. Some hope may lie in a 1981 bibliography of Bowen's work (by Sellery and Harris), but according to the introduction of The Mulberry Tree: Writings of Elizabeth Bowen (Lee, 1986), 'there are almost seven hundred entries under the section that includes reviews.' That's daunting, even if I'm only looking at the mid-Forties Tatlers. But the Big Question is: did Reed write Bowen's Tatler book reviews under his own byline, or hers? Is it possible? Are there Bowen-attributed Henry Reed blurbs littering the advertisements of literary journals from 1946? Or simply un-indexed Reed reviews waiting to be re-read?

ConscriptsAlmost a year ago, I mentioned a quote I couldn't place. In Shire's British Poetry of the Second World War, the chapter "Where Are the War Poets?" opens with the epigraph, 'To fight without hope is to fight without grace.' The quote is attributed to Henry Reed, but I haven't (yet) found where he may have written the line. I'm beginning to suspect it may lie in one of the two "Poetry in War Time" articles Reed wrote for the Listener in 1945, and which I haven't seen. (Then there's this strange anomoly.)

I do, however, know the origin of the phrase. If the words are truly Reed's, they were a response to his epony-nemesis, Herbert Read. Read's most famous poem of World War II is "To a Conscript of 1940," in which a veteran of the First World War addresses a new recruit: '... There are heroes who have heard the rally and have seenThis is not exactly the sentiment of Rupert Brooke, but Reed (as a conscript of 1941) would still have certainly been in some disagreement, even though the war, for him, was little more than a terrible personal inconvenience.

Layers of a PalimpsestThis week's mystery quote comes from a 1953 article by Ronald Bottrall, "The Teaching of English Poetry to Students whose Native Language is not English" (ELT Journal 8, no. 2 [Winter 1953-1954]: 39-44):

What, in fact, this kind of thing leads to is a Variorum edition of the poets; we have one of Hopkins already. The foreign student is particularly liable to be misled by this piling of Pelion on Ossa—at the worst he reads Gardner (W. H.) on Hopkins or Gardner (H.) on Eliot, and never gets near the poetry at all. To adopt a phrase of Henry Reed's, he is always reading the top layers of a palimpsest (emphasis mine). Unfortunately, I don't have easy access to the full text of the journal, but by doing some backwards-and-forwards searching I was able to withdraw this sizable chunk of the surrounding text. Not that the context makes it any easier to deduce the source of this particular paraphrase of Reed. I had to look up a whole bunch of stuff:

The 'palimpsest' line's provenance currently escapes me. Reed may have compared reading a particular author to only seeing 'the top lines of a palimpsest' in The Novel Since 1939 (British Council, 1946), or it may be a line he used in one his "Italian" radio plays, Return to Naples (1950), or The Great Desire I Had (1952). I guess the article is late enough for A Very Great Man Indeed (1953) to be fresh in the author's memory, but I don't recall the line being from there, either.

Guessing GamesWill this labor ever be finished? Complete? Will there ever come a day when, thumbing through the index of some quaint volume or plying the depths of some obscure database, I will suddenly discover that there is simply nothing left to discover? Not today. I am constantly amazed when I turn up Reed references which have so far managed to escape the irresistible gravity of the bibliography.

I found today's escapee as I was strolling (virtually) through the searchable database of back issues of journals at Oxford University Press, specifically Notes & Queries. Great stuff, that. (Incidentally, the 19th century stuff is online, full-text.) Undeterred by innumerable references to Wordsworth's American editor, whose name also happened to be Henry Reed, I found this in a page of search results: 'The pages under our eye did not reveal his name, and we were content to go on guessing. (It proved to be a name new to us—Henry Reed.)' Now, you have to have a special subscription to the Oxford University Press Journals to view articles prior to 1996. However, if you browse instead of search, the "Front matter" (table of contents) is thoughtfully provided. The article in question, "Memorabilia," happens to be on page 1 of volume 188, no. 1 (13 January 1945), and is included with the scan! It's an unsigned article reacting to a review of Eliot's "new book," Four Quartets, which appeared in the December 9th, 1944 Time & Tide. Here's the rest of the quote: 'It does not disquiet me that there are passages in these four poems that I still do not understand, for whenever I read them, as I do often, the wonderful varied power of the language they employ holds me completely a victim, and I do not mind the uncertainties.' When we had read as far as that, in the Time and Tide review (9 December) of Mr. Eliot's new book, we knew that here was a mind we must respect. The pages under our eye did not reveal his name, and we were content to go on guessing. (It proved to be a name new to us—Henry Reed.) The author (whose name I may try to guess), then goes on to compare Reed's review in favor of one by E.J. Stormon, from the Winter, 1944 Meanjin Papers. Now, I'm familiar with the journal Time & Tide, having taken an extended traipse to pursue a volume at Duke's libraries in order to obtain Walter Allen's review of Reed's A Map of Verona. At the time, I had scanned Duke's volumes looking for more of Reed's work, but this review must have slipped by. It may have been unsigned as well, as "Memorabilia"'s author suggests. And if I had to take a guess at the name of this author? Mr. Walter Allen, I presume?

Where Are the War Poets?The question everyone was asking in the late 1930s and early 1940s was "Where are the war poets?" There was no Brooke, no Sassoon, no Owen. John Lehmann asked it. Wilfrid Gibson asked it. Robert Graves asked. C. Day Lewis asked, and answered:

They who in folly or mere greedRather, I prefer E.M. Forster, who frankly declared, "1939 was not a year in which to start a literary career." An addition to the Criticism pages: an excerpt on Reed from Linda M. Shires' British Poetry of the Second World War (New York: St. Martin's, 1985). Shires has written one of my favorite lines in summarizing "Naming of Parts": 'The speakers are soldiers, yet the most important feelings in Reed's poem are not spoken, as though the private man has no voice worth hearing compared with man-as-soldier' (p. 82). It's a fine piece, which I had actually acquired over a year ago but failed to transcribe, time lost to obsessive tinkering with the database, trying to get the bibliography to sort properly. One thing is bothering me, however, and that's the epigraph to the chapter entitled "Where Are the War Poets?" Shires has credited Reed with the line "To fight without hope is to fight without grace." At first, I thought this was part of the Lessons of the War series — "Unarmed Combat" perhaps — or some draft I had seen but not taken sufficient note of. To fight without hope is to fight without grace. Is it from an article in The Listener? A radio talk? I can't find that line, not anywhere.

Handy ManI fixed my kitchen sink tonight. The faucet stem was leaking from the swivel that allows it to move back and forth over the two split sinks, and it was dripping in the cupboard underneath, wreaking wet havoc on my collection of plastic grocery bags.

I am not the handiest of men. Still, I have a few rudimentary tools—a wrench, pliers, screwdrivers, a claw hammer—and just enough confidence to believe I can reassemble a faucet, leaving it (at least) no worse off than it was before I took it apart. I know that turning a water cutoff valve to the right should turn it off (righty-tighty, lefty-loosey), and I religiously watch "This Old House". So, a little Teflon plumbing thread tape and an hour later, I have a decidedly undripping, non-leaky kitchen sink. A truly handy gentleman to have around would be someone like David G. Kendall, Professor of Mathematics and Fellow of the Royal Society of London. He has published his theories on such diverse topics as queueing ("Some Problems in the Theory of Queues." J. Roy. Statist. Soc. Ser. B 13 [1951] 151-185), comets ("The Distribution of Energy Perturbations for Halley's and Some Other Comets." Proc. Fourth Berkeley Symp. Math. Statist. Probab. 3 [1961] 87-98), and bird migration ("Pole-Seeking Brownian Motion and Bird Navigation." J. Roy. Statist. Soc. Ser. B [1974] 36 365-470). In a paper on seriation (a common archeological tool used to date objects by arranging them in a chronological series), I discovered a reference to, of all things, Reed's "Naming of Parts": 'The arable fields are not shown, and a large-scale pre-enclosure map of Whixley is one of those things, which, in our case, we have not got (Reed, 1946)' ("Recovery of Structure From Fragmentary Information." Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. Ser. A 279 [1975] 562. Italics mine). After scanning the paper (and understanding about one paragraph in four), I was more surprised that "Judging Distances" was not the poem quoted from A Map of Verona. I imagine Professor Kendall would have taken special delight in the duelling lines "Maps are of place, not time," and "maps are of time, not place...". A contemporary of Reed's, Kendall was posted to the PDE (Projectile Development Establishment, "Please Don't Enquire!") in the west of Wales during World War II, where he helped develop rocket technology as a statistician. In 1946, he returned to academic life, teaching mathematics first at Magdelan College, Oxford, followed by an appointment to the University of Cambridge in 1962 (picture). A truly absorbing interview with Professor Kendall (contains link to .pdf file) was printed in the journal Statistical Science in 1996. Astronomy. Rocketry. Mountaineering. Everything but the kitchen sink.

Hey Diddle DiddleHey, diddle, diddle,A mysterious quote turned up in an article from the Irish Times, reporting on a 'light-hearted "examination" of nursery rhymes' from an RTE radio program (Browne, Harry. "Plenty of Questions But Too Few Answers," 22 February 2002, 55.) The article quotes a "Sir Henry Reed," who summarizes "Hey Diddle Diddle" thusly: 'It commemorates the athletic lunacy to which the strange conspiracy of the cat and the fiddle incited the cow.' Could this be our Henry? It certainly sounds like him. A search for the quoted phrase brings up a Yale Review of Books article on the futility of deconstructing children's verse. The quotation is dropped during a discussion of a popular book on the history of nursery rhymes, Mother Goose: From Nursery to Literature (Gloria Delamar, 1987). Is this the source of the mysterious "Sir Henry Reed" quote? If it is, indeed, the Henry Reed, where does the titular "Sir" come from? Do you have this book in your library? Drop me a line at steef at solearabiantree dot net.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||