|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Books"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

In the newly published Selected Letters of Anthony Hecht (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), edited and by Jonathan F.S. Post, we find a letter to fellow poet J.D. McClatchy, reacting to the 1995 publication of Touchstones: American Poets on a Favorite Poem (University Press of New England), to which Hecht had contributed an essay on " Gaze Not on Swans" (attributed to William Strode and Henry Noel).

An American contemporary of Henry Reed's, Hecht saw combat in World War II, and was particularly affected by his experience liberating Flossenbürg concentration camp in April of 1945. With few exceptions, he finds little good to say about the Touchstones anthology, and takes a particular exception (Google Books preview) to Marvin Bell's piece on Reed's " Naming of Parts": December 19, 1995 Washington DC

[To J.D. McClatchy]

Dear Sandy,

I imagine you're away now, either in England or California (I can't keep your travels straight in my memory) but I have just read your excellent little essay on Pope's "Epistle to Miss Blount," and read it not only with delight but with greatly moved feelings. Your essay, brief as it is, seems to me the best thing in the whole book called Touchstones. It is in many ways an odd book. I haven't read it all, and don't think I ever will; but I feel I must surely have covered both the best and worst of it. And these "best" and "worst" fall with astonishing neatness into two distinct camps that are easy to characterize. Let me say right away that I think the "best" are, after you, Wilbur, Justice, Nims (and there may be one or two others as yet unread). The other category is more numerous, and, as I was composing it I began to think I was, as I have long been accused of being, a misogynist, male-chauvinist pig. For my list includes (in no preferential order) Linda Pastan, Maxine Kumin, Erica Jong, Clara Yu, Rosellen Brown, Nancy Willard, Chase Twichell, and (saved by the bell) Marvin Bell.

...All of them, in any case, begin auto-biographically, with a sickening narcissism [and seem] to come to the poem they are ostensibly writing about with some reluctance. They feel all cuddly or martyred about their past, and this is what truly moves them...[.]

But in some ways Bell deserves a special trophy for incomprehension. It's not just that he begins with his own trifling army experience in writing about Henry Reed's "Naming of Parts." It's that there is so much about the poem he fails to grasp, not the least of which being the very clear and touching class distinction between the conscript and the staff sergeant who is lecturing. The difference would be ironically amusing (or mildly offensive) under normal circumstances: the intellectually inferior lecturing his better. But in war time, such roles are either irrelevant or reversed. And the recruit must put up with them not merely because army regulations require his obedience but because his life may depend on knowing what this well-meaning oaf is trying to impart. And all the grounds for resentment are thereby cancelled, and a new, not entirely desirable, basis for existence is established. The wistfulness of the recruit for the pastoral world of harmless nature, and the recollected world of lovers, is juxtaposed, as it was in Hardy's "In a Time of Breaking of Nations," with the familiar irony of war-time brutality.

Anyway, the book is, but for your piece, and one or two others, a silly book, eliciting the worst, the most hopelessly self-absorbed from writers who are far too self-absorbed...[.]

...With warmest and most affectionate wishes for the holiday season and the coming year,

Tony [pp. 274-275]

It's obvious that Hecht holds Reed's poem with special regard—no doubt from the familiar experience of basic military training—and the comparison with Hardy is both apt and doting. Hecht does not appear to be one to suffer fools lightly, but Bell served as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, so perhaps the criticisms regarding the other contributors' narcissism and self-absorption are heavy-handed. As a matter of fact, if you have read the entire letter, it sounds suspiciously as though Hecht may have misunderstood the editors' intentions for the collection.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

A critique of the design of the 1947 American edition of Reed's poems, from Bookbinding and Book Production, 1948 (p. 85):

A Map of Verona

By Henry Reed. 5¼ x 8½. $2.50.

Publisher: Reynal & Hitchcock, Inc.

Manufacturer: Cornwall Press

Type: Lino. Electra 10/13: 24x38

Stock: Perkins & Squier 60, 2R

Binding: Athol Teralin, light green

Stamping: dark brown ink

Designer: Gerald Gross

The format for this collection of poems is without stimulation. The case is stamped only on the length of the spine in brown ink and the pattern and color of the cloth is uninspired. The book is rough trimmed; my own inclinations are always to trim, unless hand made paper or a deckle edged sheet is used. The presswork-lineup and binding are poor. There is little correlation between the front matter pages and the tenor of the text, and it would seem that the designer didn't have enough time to pay the necessary attention to details. The poetry is nicely set in Electra 10/13 with with heads in 12pt. Roman caps in Bodoni Book. The folios could have been larger than the 8pt. italic: this way they look as though they were trying to hide. The author is a man of considerable verbiage and very often there are one word runovers and where these occur, they are flushed right, directly under the end of the preceding line, it may make for easier carry-over of thought, but I'm not sure that the effect is pleasing when looking at the page. I didn't waste time sending my eye back to the beginning of a new line, but I did fumble at first until I was able to adjust to it. '[A] man of considerable verbiage.' There's an understatement. If there is a British analogue of this publication, I'd love to see the entry for the 1946 London edition, published by Jonathan Cape.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

Recently published by Cambridge University Press is Kate McLoughlin's Authoring War: The Literary Representation of War from the Iliad to Iraq. McLoughlin is a Lecturer in English Literature at Birkbeck College, University of London, and has previously edited The Cambridge Companion to War Writing (2009). From the publisher's description:

Kate McLoughlin's Authoring War is an ambitious and pioneering study of war writing across all literary genres from earliest times to the present day. Examining a range of cultures, she brings wide reading and close rhetorical analysis to illuminate how writers have met the challenge of representing violence, chaos and loss. War gives rise to problems of epistemology, scale, space, time, language and logic. She emphasizes the importance of form to an understanding of war literature and establishes connections across periods and cultures from Homer to the 'War on Terror'.

You can also find a substantial preview of Authoring War on Google Books. McLoughlin devotes three pages to Reed's Lessons of the War sequence, from "Naming of Parts" ('begins the process of transforming non-combatant experience through the replacement of civilian by military language and semantics'), through " Returning of Issue":

The final part of 'Lessons of the War' is 'Returning of Issue', which takes the form of a discharge talk by the sergeant. The men are standing inside now because it is autumn, and through the window the recruit-speaker notes a coming down to earth of 'small things' turning and whirling in the wind. He is unable to tell whether these small things are 'leaves or flowers': it is as though his perception has been thoroughly miltarised, so that he is no longer capable of appreciating the realm of almond-blossom, japonica — and love. Indeed, the sergeant remarks, 'I think / I can honestly say you are one and all of you now: / Soldiers'. In this section, as in the others, Reed exploits the military and civilian meanings of a phrase: here, 'Returning of Issue' denotes not only the giving back of kit after service but the prodigal son's return to his father. The recruit-speaker is unable to return to his father — significantly, his parent's fields are 'sold and built on' — and so elects to stay in the army. The actual terrain on which his peacetime identity was grounded has been irretrievably lost, and so he decides to remain, not a person, but 'a personnel'. In turn, he will himself 'teach: / A rhetoric instead of words; instead of love, the use / Of accoutrements'. His consciousness has forever changed — 'I have no longer gift or want' — and so his place must change too. (p. 105) is due to be released in the States on March 31, and is available for pre-order on Amazon.com.

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

In November of 2006, Professor Jon Stallworthy gave a talk at the Poetry Trust's Aldeburgh Poetry Festival ( picture), entitled "Henry Reed: The One-Poem Poet?" The talk was, admittedly, a reworking of the introduction to Reed's Collected Poems (1991), in which Stallworthy refutes the idea that "Naming of Parts" will forever eclipse any other poetry Reed had attempted to write, and argues that Reed can finally, at "everlong last, take his rightful place at 'the starry feast'" ( Aubrey de Vere).

Stallworthy has a new book just out, Survivors' Songs: From Maldon to the Somme, a "series of poetic encounters with war." There are essays on Brooke, Sassoon, and Owen (Stallworthy has both written a biography, and edited the definitive edition of Owen's poems), and the the chapter, "Henry Reed and the Great Good Place": the revised text of Stallworthy's original introduction, which likely made up his 2006 talk at Aldeburgh.

Click the book icon to preview

this title in a new window.

In an introductory "Voice over" to the new book, Stallworthy defines his purpose in collecting these stories: "Good poets are survivors — even if, like Keats and Owen — they die at twenty-five."

I have spent many of the most rewarding hours of my life listening to the voices of absent friends — Thomas Hardy, William Yeats, Wilfred Owen, David Jones, Wystan Auden, Keith Douglas, and Old Uncle Tom Eliot and all — singing of human unsuccess

In a rapture of distress; and I think of the essays in this book as thank-you letters expressing gratitude in terms that, I hope, may lead other readers to listen to their voices and hear in them what I have heard. (p. x)

I am eager to get a copy of Survivors' Songs, and thanks to folks at Cambridge University Press and Amazon.co.uk, much of the book is available to be previewed (CUP even provides the handy book widget, seen above). Already I am noticing items I missed in previous versions of Reed's chapter: Reed and Ramsbotham took "civilian" lunches in Leighton Buzzard to get away from Bletchley; they briefly rented a house in Charlestown, Cornwall, in July, 1946; Reed's arrival in Verona in 1951 was heralded on the radio (he learned, later on, "with much delight"); there is a long poem, still in manuscript—possibly set during the American Civil War—alternately called "Matthew" or "In Black and White."

There is still much to be gleaned from the work set down by Professor Stallworthy, and readers have been given a second chance to really listen, and hear the voices that he has heard.

|

1538. Walker, Roy. "Betti and the Beast." Listener 58, no. 1492 (31 October 1957): 713-714.

Review of Henry Reed's translation of Ugo Betti's Irene, broadcast on the Third Programme on October 20, 1957.

|

Just in time for the holidays, Oxford is reissuing (for the second time) their Oxford Book of War Poetry, edited by Jon Stallworthy (who also edited Reed's Collected Poems). The anthology contains Reed's original three Lessons of the War poems: "Naming of Parts," "Judging Distances," and "Unarmed Combat."

D.J.R. Bruckner, in the New York Times, had this to say about the Oxford War Poetry, first published in 1984:

Mr. Stallworthy comes well prepared to write about that breed. His biography of Wilfrid Owen swept the field of prizes when it appeared; he is the definitive editor of Owen's poems and his knowledge of war literature is wide. In his introduction to this anthology he traces the lineage of World War I poets to the 18th-century English public school, its curriculum chock full of ancient heroic poetry which upper-class youth took as personal inspiration. By 1918 the ideal had died with the class in the in the trenches. The emotional power of the poems written by the best of the group comes not only from their recognition of the degradation and hopelessness of soldiers, but from a feeling they were turning their backs on their upbringing. They would never again believe with James Thomson that 'guardian angels' sang the refrain of his hymn, 'Rule, Britannia!' ("No More Famous Victories," February 24, 1985, p. 340)

Stallworthy also talks at length about war poetry in the documentary Voices in Wartime ( transcripts of interviews). Here's Oxford's catalog page for the second reissue paperback.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

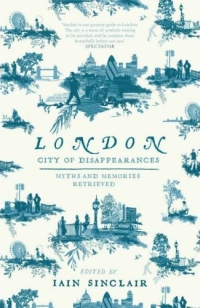

I returned recently to a book I first looked at back in October of 2006: London: City of Disappearances, edited by Iain Sinclair. A huge collection of stories about a London which no longer exists (or never was), it contains a small chapter by Richard Humphreys, " Death of a Cleaner," in which Humphreys attempts to discover something, anything, about his London house cleaner's enigmatic life, following the man's untimely death. 'Not everyone has a house cleaner who knew Dylan Thomas and Francis Bacon,' Humphreys begins, 'and who was born into an aristocratic family and went to Wellington College and Cambridge University. I had one, called Mr [Antony] Ashburner, and he disappeared from my life as suddenly as, fifty years before, he had disappeared from the life of his own family.'

I was surprised, on re-reading the chapter, on how many connections and confirmations to the story I had uncovered in the last two years, in the span of a couple of paragraphs:

I cannot follow them into their world of death,

Or their hunted world of life, though through the house,

Death and the hunted bird sing at every nightfall.henry reed, 'Chrysothemis'

According to his sister, [Ashburner] went up to Cambridge in 1939 to read law. If he did go to Cambridge it didn't suit him and he transferred to Birmingham, where he probably read English. There is a mysterious and evocative poem by the Birmingham poet Henry Reed, called 'Chrysothemis', 1 which gives an insight into Ashburner's life in the Second City. After his death, I found a galley proof of the poem in his untidy flat at the wrong end of Ladbroke Grove. There was a dedication, handwritten in ink: 'To Antony from Henry, December 1942'. The poem is darkly Eliotic and casts light on an important, if brief, relationship. It was published in John Lehmann's New Writing and Daylight that winter.

In a letter of 1965 — to Dorothy Baker, 2 a BBC Third Programme script-editor — Ashburner recalls this acquaintance during a brief spell when he was living in the basement flat of a house belonging to Professor Sargent Florence, the left-wing economist and sociologist. This was Highgrove, 3 a Birmingham house famous enough to be the subject of a short TV film by David Lodge. 4 Ashburner's flatmate was Dr Bobby Case, a pathologist at St Chad's Hospital. 'I wondered then,' he wrote to Baker, 'and I have sometimes wondered since, how it was that Bobby Case managed to get hold of so much offal for our dinners — in view of wartime shortages. . .'

Highgrove, a large house, now demolished, was the haunt of writers and radicals, such as Auden and Spender, as well as the novelist and Birmingham University lecturer Walter Allen 5 — whose name can be found in Ashburner's surviving address book. Highgrove was a Midlands bohemian hang-out unknown to most metropolitans. Perhaps, like Julian Maclaren-Ross, 6 another acquaintance, Ashburner was one of the misfits and deserters incarcerated in the psychiatric wing of Northfield military hospital [Wikipedia] in the Birmingham suburbs, one of W. R. Bion's [Wikipedia] patients (guinea pigs).

What else did he do in the war? Reed went on to work at Bletchley Park. My mother-in-law, who was in the same section, remembers him taking a female colleague out for lunch. Reed's Bletchley Park friend, Michael Ramsbotham, has no recollection whatever of Ashburner. Was he a conscientious objector? In my more fanciful moments I imagine he was a spy, although I'm not sure which side he would have been on. By the end of the war he was living in Fitzrovia and working at Foyles bookshop. He wasn't keen on Christina Foyle [Wikipedia], he told me.

1. ^ Reed's poem, "Chrysothemis," is a monologue spoken by the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemestra, sister of Orestes and Electra. The poem is quoted at length in Gross's Sound and Form in Modern Poetry.

2. ^ Dorothy Baker shows up as part of Conroy Maddox's Birmingham entourage in Silvano Levy's The Scandalous Eye.

3. ^ Highfield Cottage (not "Highgrove", as Humphreys would have it), was the home of Louis MacNeice while he was a lecturer in Classics at the University of Birmingham in the 1930s. The house is one of the landmarks in this map of The Life and Times of Henry Reed.

4. ^ The television documentary in which Highfield figures prominently is As I Was Walking Down Bristol Street.

5. ^ Walter Allen was a schoolmate of Henry Reed's at King Edward VI Grammar School, Aston, and both men went on to the University of Birmingham.

6. ^ Henry Reed seemed to have a special hatred of Julian Maclaren-Ross, and wrote several negative reviews of his work for the New Statesman. In his book, Fear and Loathing in Fitzrovia (2003), Paul Willets quotes one review in particular, from March 2, 1946:

Like its predecessor, Bitten By the Tarantula attracted some scathing reviews. And, once more, the severest of his detractors was Henry Reed, whose hatred of Julian's work was fortified by a hatred of Julian himself. 'Mr Maclaren-Ross's book,' he wrote, 'is very well bound and generously, though not elegantly printed; but its last three pages increase their number of lines from thirty-four per page to forty-one, thereby giving a peculiar stretto effect to the narrative which is, in fact, its sole interest. [...] The point of Mr Maclaren Ross's novel is not obscure. It has none.' (p. 189)

In defense of his character, Maclaren-Ross had an ally at the BBC in producer Reggie Smith, also a Birmingham colleague of Reed's.

City of Disappearances is due out in paperback this fall.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

In today's Observer, Adam Phillips reviews the new edition of Reed's Collected Poems ( text only):

Reed has a plain eloquence for what goes wrong and for what then holds absurdity at bay. In 'The Door and the Window', a love poem about an absent lover, he writes of 'Waking to find the room not as I thought it was,/ But the window further away, and the door in another direction', as if the room (or the lover) in the world should match the room in the mind and that only in language can a door change direction or have any direction at all. Reed wants to show us, without melodrama, how disoriented we are by what language lets us do, what language lets us notice: 'It is not that courage has risen,' Antigone says in Reed's poem of that name, 'but that fear has failed for a moment.'

The Collected Poems of Henry Reed is available for purchase through the Guardian Bookshop.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

This recent feature in The Guardian, " In the Line of Fire," again asks the question, "Where are the war poets of this war?" (see " To the Poets of 1940," previously). In answer, the article suggests there is 'one book of high-quality poetry about the Iraq war': Here, Bullet, by Brian Turner.

Henry Reed also receives passing mention, along with fellow Second World War poets Alun Lewis and John Pudney. As part of the legacy of critics asking "Where are the war poets?", the article mentions an editorial from the August 8th, 1942 Times Literary Supplement: " Poets in War" (2MB .pdf). Of course, I looked it up:

POETS IN WAR Where are the poets of the war? This question is often asked by those who remember that the last war threw up a fair amount of notable poetry. And that is true; for there were then living several highly skilled and experienced poets—Bridges, Kipling, Hardy, and there can be added Doughty, all of whom had something eloquent to say about the war or about aspects of it. But they, and others, were established writers; they viewed the war through the accumulated knowledge and wisdom of years; they were not soldiers, neither were they liable to be called up. Nor, when one thinks of it, have there ever been many poets of war who have been at the time of writing on active service, though the last war produced several poems by fighting men, like Julian Grenfell and Rupert Brooke, which are not likely to be forgotten. The fighting man, however, who writed about war is exceptional, and none too common is the soldier who sings of war years afterwards. Full of war as European poetry is, the singers of war have been for the most part not soldiers. Aeschylus, it is true, is said to have taken part in Salamis, and his narrative of that battle reads like participant's. Nearly all the epics are of war: and Homer's audience clearly delighted in it, but to the humane Virgil it was essentially a matter for sorrow and pity. Tyraeus, the Greek elegist, was certainly a warrior: and he appears to have seen war at too close quarters to glorify it.

Thoughts such as these are almost inevitable when “Poems of this War,” reviewed on another page, invites attention. The contrast is great. For this anthology is not the work of old hands, exempt from the liability to serve, but of the younger writers, all presumably of military age, where, as some of them certainly are, actually serving, or not. The anthology then shows how the war affects the youngest generation of those who make poetry the vehicle of their thoughts. Or, to be cautious, how it affects particular representatives of that generation picked by particular editors. That they write with complete sincerity is not to be doubted; they say what they wish to say in their own language; and yet, as Mr. Blunden in his introduction implies, there is much that is traditional in war poets which is not to be found in them. There is “no militarism, or personal claim, or study of revenge.” This is a remarkable comment to make. Militarism is no doubt offensive even in professional soldiers, many of the best of whom have been free from it. Personal claims, again, may be sheer egoism. Revenge may be an injurious study. But is there no such thing as righteous indignation? May not a dear homeland be in imminent danger? That war is a foul way of living, that all things pleasant and legitimate are shattered by it, that soldiering, even in the best cause, may be at times and to some temperaments an unmitigated bore—all this is true; and there is a middle generation living which has been through it all. No doubt, however, war was to that generation more of a novelty than it is to the latest, which was born in its atmosphere and bred up in its aftermath.

These poems, Mr. Blunden tells us, have been written on the principle of the “innocent eye.” The mood of this volume is “seeing where the truth is.” So far, so good; but may not the eye in the innocence of youth miss things which older commentators, equally innocent, will have acquired the habit or the power of discerning? Can anything like the whole truth about so vast a subject, so ubiquitous a presence, as universal war, be revealed to any eye? The facts here are admittedly in various moods. Some of them are in the trenches or entering battle; others share the common danger of being bombed; others meditate on natural beauty, on love, on friendship, on death and life. They are quite candid. They are oppressed by the calamity which has befallen the world. In vain to remark that they are not old enough to look back on much in tranquility. Yet they must be taken for what they say and for what they do not say, as a symptom, because they express themselves without labour. To read them is to infer that, were there no war, they would still be poets, but poets compelled, like all too many children of this age, to think, observe, and write within a narrow living-space. Also reviewed in this issue are Poems of This War: By Younger Poets (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1942), edited by Patricia Ledward and Colin Strang ("Songs of Emergency," p. 392), and volumes by Sidney Keyes, Alan Rook, Keidrich Rhys, and John Heath-Stubbs.

By coincidence, August 8th, 1942—the day this editorial appeared in the TLS—was the very day Reed's " Naming of Parts" was printed in The New Statesman and Nation.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

I've been busy busy busy with library business at work, and haven't had much time for updating here, I'm afraid. Ten-hour+ work days don't leave a poor clerk, however glorified, with energy left over for pleasure-librarying. Tisk tisk. But I have noticed that Carcanet Press' forthcoming reissuance of Reed's Collected Poems has made it to Amazon.com proper, whereas it formerly appeared only on Amazon.co.uk.

The real news is that Carcanet's page for the Poems now shows that, in addition to being edited by Jon Stallworthy, the paperback will include a Foreword by critic Frank Kermode. That will certainly breathe fresh life into the re-release of Reed's poetic oeuvre. Kermode knew Reed personally, both in London and while Reed was teaching at the University of Washington, Seattle, in the mid-1960s.

I do hope Kermode's Foreword does not come at the sacrifice of Stallworthy's excellent Introduction to the original Oxford Poets collection. (I also hope, if they are using the text of Kermode's 1991 review of the Collected Poems, that Carcanet has caught his incidental inversion of 'duellis' and 'puellis', from Horace's Odes and in Reed's "Naming of Parts.")

Let's see: Carcanet has the Collected Poems (ISBN-13: 978-1857549430) listed for £11.69, available in July. Amazon.co.uk has it for just £8.54, beginning July 26th. And Amazon.com has it for $23.95, available on August 1st. A little quick currency conversion, and we get that £8.54 is currently worth roughly $16.86, so perhaps it's cheaper to buy it from the UK, but with shipping it's probably a wash. We'll see!

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

Sidney Keyes was a youthful poet killed before he had time to register the impact of warfare; Alun Lewis registered the deadening effect of regimentation and the stimulus of travel, but left no record of the military action it seems it was his destiny to seek. Douglas sought action, found it, recorded it and his fear of its consequences, before he too died. Roy Fuller was excluded by circumstance from action and was able, literally from a distance, to mark the changes that wartime forced on society and the enclosed microcosm of the services. Each is an individual experience, and it is because of the quality of their work that they are accepted as the chief poets of the Second World War. But it is appropriate that none of them wrote the poem of the Second World War. That was written by Henry Reed.

Thus begins Robert Hewison's analysis of Reed's Lessons of the War poems, in the book Under Siege: Literary Life in London, 1939-1945 (Oxford, 1977). Interestingly, Hewison treats the whole sequence as a single work, mentioning, but not lingering on (or even quoting from), "Naming of Parts."

Hewison prefers instead to look at " Judging Distances" at some length. 'In this case the landscape has to be interpreted in formal terms; the distance cannot be judged emotionally, the territory must be seen as a map. But in the trainee-soldier the surviving civilian persists in reading the topography with his own eyes...' (p. 139). Though Hewison has chosen a slightly less famous poem, the resulting commentary is familiar: 'Individuality has to be sacrificed to the needs of the military machine, the landscape reduced to the terms of tactical necessity, but some small item of personality could be retained — the observing eye of the poet' (p. 140).

He then turns to " Unarmed Combat," the last of Reed's Lessons published during wartime, concluding, 'Henry Reed achieves a rare fusion between soldier and poet of the Second World War...' (p. 140).

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

Amazon.co.uk has an updated page for Carcanet's forthcoming paperback edition of Reed's Collected Poems (due out this July), with a super-large cover image (see " Collected Covered," previously). Available for pre-order, now!

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

So, I had my credit card info stolen this week. That was fun. You should have heard the conversation I had with customer service when I called to cancel the card: Amazon.com? No, that charge is legitimate. Barnes & Noble? Yeah, that was me, too. Abebooks.com? Okay, if it was for books, then it was probably me. A new card should come this week.

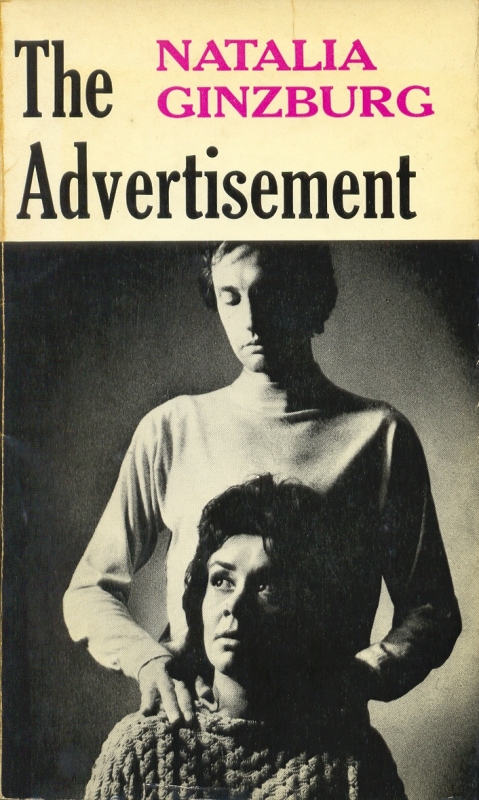

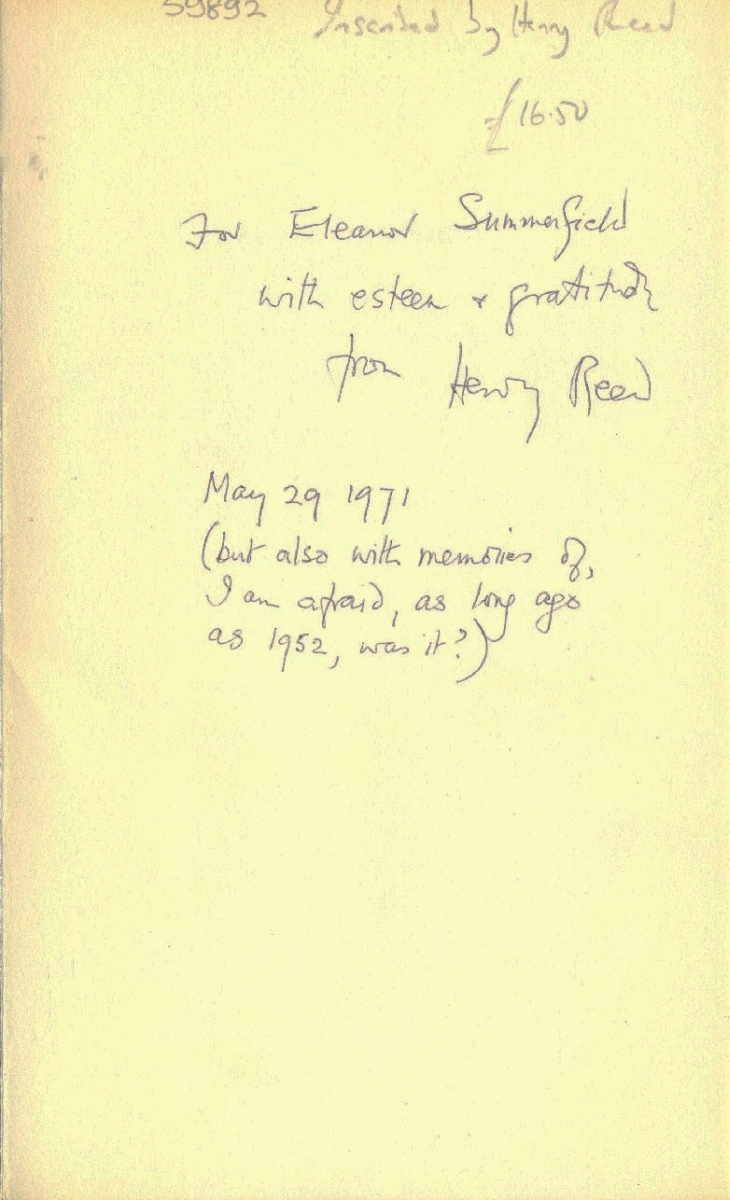

This month's extravagence was a signed copy of Natalia Ginzburg's The Advertisement ( L'Inserzione), published in 1969 by Faber and Faber, and translated from the original Italian by our very own Henry Reed. I don't usually bother with first editions or signed copies, but I felt like I deserved a treat.

Now, I must admit, I have only a passing interest in Reed's translations. What I'm really after is completeness, an inclusive collection. Even the items I'm least interested in may turn out to contain an overlooked fact or hidden clue to some larger mystery, rounding out Reed's bio-bibliography (biblio-biography?). This edition of Ginzburg's play, for instance, has a brief "Translator's Note" written by Reed, the details of the first stage performances in London, and a jacket blurb from a Daily Telegraph review: 'From the moment this very interesting play takes shape, it is clear that a tour de force is necessary from the actress playing Teresa; and Joan Plowright rises to the challenge quite superbly.'

And then there is the inscription to my newly-acquired copy:

For Eleanor Summerfield

with esteem + gratitude

from Henry Reed

May 29 1971

(but also with memories of,

I am afraid, as long ago

as 1952, was it?) Ms. Summerfield (BBC obituary), I was delighted to discover, was an accomplished actress, with a litany of film (Internet Movie Database) and radio (BBC Programme Catalogue) credits to her name. She was married to the actor Leonard Sachs for 40 years (though she could claim Sir Richard Burton among the paramours of her youth.) I imagine Reed was introduced to Summerfield while he was writing for the Third Programme. How they became reacquainted in 1971, I have no idea. At the BBC, again?

To see more on this book and and others by Reed, take a peek at my bookshelf on LibraryThing.

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

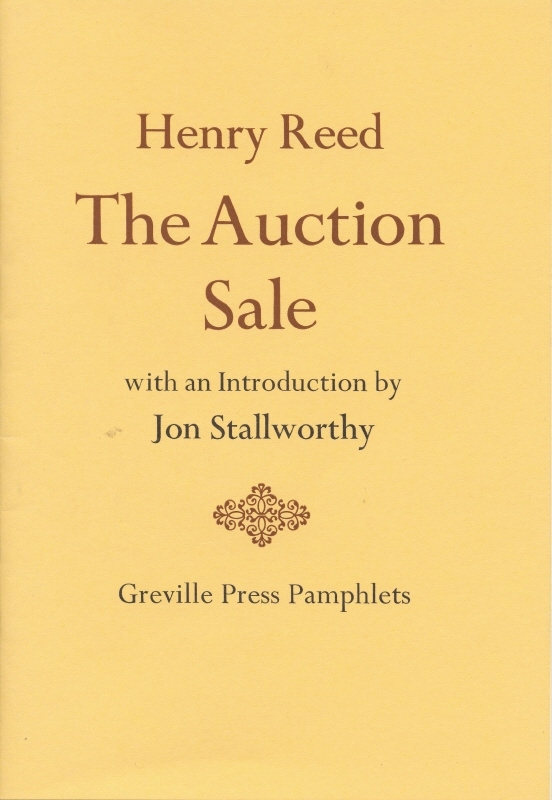

"The Auction Sale," according to Professor Jon Stallworthy, is Henry Reed's 'most ambitious exploration of the landscape of desire' (Introduction to the Collected Poems, 1991). It was written in 1956, and first published in the journal Encounter, in October, 1958. It's a long poem—in excess of 300 lines—in the vein of Thomas Hardy. Set in Dorset at a country auction, it concerns a rousing bidding war over a painting, 'told in a voice as flat as if the speaker were reading from a country newspaper' (Hardy collected local newspaper stories as sources of inspiration):

The auctioneer again looked round

And smiled uneasily at friends,

And said: "Well, friends, I have to say

Something I have not said to-day:

There's a reserve upon this number.

It is a picture which though unsigned

Is thought to be of a superior kind,

So I am sure you gentlemen will not mind

If I tell you at once before we start

That what I have been asked to say

Is, as I have said, to say:

There's a reserve upon this number." In Reed's trademark technique of pitting two duelling voices against each other, the grey November setting and flat repetition of the auctioneer stand in stark contrast to the lyricism of a mysterious bidder's desire for a classical painting:

Effulgent in the Paduan air,

Ardent to yield the Venus lay

Naked upon the sunwarmed earth.

Bronze and bright and crisp her hair,

By the right hand of Mars caressed,

Who sunk beside her on his knee,

His mouth towards her mouth inclined,

His left hand near her silken breast.

Flowers about them sprang and twined,

Accomplished Cupids leaped and sported,

And three, with dimpled arms enlaced

And brimming gaze of stifled mirth,

Looked wisely on at Mars's nape,

While others played with horns and pikes,

Or smaller objects of like shape. Although "Naming of Parts" will always be my favorite, the supreme story-telling and quiet emotion of "The Auction Sale" lends it a special place in my pantheon of Reed's poems. I still remember, clearly, the day I first came across it, collected in Untermeyer's Modern British Poetry at my public library. An undiscovered poem. I recited the whole thing from my wrinkled and well-read photocopy at a local poetry reading, when I had nothing new of my own to share. (I think my interpretation put the crowd at the Daily Grind to sleep that night, despite the legal addictive stimulants. Did I mention it's like, 300 lines long?)

The Auction Sale was published in 2006 as a Greville Press pamphlet. The Greville Press was founded in 1979 by Anthony Astbury and Geoffrey Godbert, with the "enthusiastic support" of Harold Pinter, and the imprint has published the poetry of George Barker, David Gascoyne, W.S. Graham, Edna O'Brien, C.H. Sisson, and David Wright, among others. This collectible edition of Reed's poem includes a critical and biographical introduction by Jon Stallworthy (edited slightly from his Introduction to the Collected Poems).

You can order a copy through Amazon UK, or, if you're feeling adventurous, I have an extra copy to trade. Come back and visit again, for more details. (Bookmark this site: CTRL-D).

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

Microsoft has released in (βeta) their Live Search Books, which contains searchable scans of thousands of pre-1927 titles in the public domain. More information is available on Live Search's Weblog.

Unfortunately, for our purposes, this is slightly less than useful. Let's see: " Thomas Hardy." Good! " Ezra Pound." Okay. " T.S. Eliot?" Not so much. Oh, well.

Microsoft has also gone live with Live Search Academic, their response to Google Scholar.

|

1528. Manning, Hugo. "Recent Verse." Books of the Day, Guardian (Manchester), 31 July 1946, 3.

Manning feels that 'Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship.'

|

In 1995, to coincide with National Poetry Day, BBC1's television program, "The Bookworm," conducted a six-day poll of the public, seeking Britain's favorite poem ( Independent (London), 13 October 1995). 7,500 votes cast narrowed down 1,000 choices to the 100 best-loved poems. Henry Reed's "Lessons of the War" was ranked at #38:

1. Rudyard Kipling, "If"

2. Alfred Lord Tennyson, "The Lady of Shalott"

3. Walter de la Mare, "The Listeners"

4. Stevie Smith, "Not Waving but Drowning"

5. William Wordsworth, "The Daffodils"

6. John Keats, "To Autumn"

7. W.B. Yeats, "The Lake Isle of Innisfree"

8. Wilfred Owen, "Dulce et Decorum Est"

9. John Keats, "Ode to a Nightingale"

10. W.B. Yeats, "He Wishes for the Cloth of Heaven"

11. Christina Rossetti, "Remember"

12. Thomas Gray, "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard"

13. Dylan Thomas, "Fern Hill"

14. William Henry Davies, "Leisure"

15. Alfred Noyes, "The Highwayman"

16. Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress"

17. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach"

18. William Blake, "The Tyger"

19. W.H. Auden, "Twelve Songs"

20. Edward Thomas, "Adlestrop"

21. Rupert Brooke, "The Soldier"

22. Jenny Joseph, "Warning"

23. John Masefield, "Sea-Fever"

24. William Wordsworth, "Composed Upon Westminster Bridge"

25. Elizabeth Barrett-Browning, Sonnets From the Portuguese, XLIII ("How Do I Love Thee?...")

26. T.S. Eliot, "The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock"

27. John Masefield, "Cargoes"

28. Lewis Carroll, "Jabberwocky"

29. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, from "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner"

30. Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ozymandias of Egypt"

31. Robert Frost, "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening"

32. Leigh Hunt, "Abou Ben Adhem"

33. Siegfried Sassoon, "Everyone Sang"

34. Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Windhover"

35. Dylan Thomas, "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night"

36. William Shakespeare, Sonnet 18 ("Shall I Compare Thee...?")

37. W.B. Yeats, "When You Are Old"

38. Henry Reed, "Lessons of the War" (To Alan Michell)

39. Thomas Hardy, "The Darkling Thrush"

40. Allan Ahlberg, "Please Mrs. Butler"

41. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan"

42. Robert Browning, "Home Thoughts, From Abroad"

43. John Gillespie Magee, "High Flight (An Airman's Ecstasy)"

44. T.S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi"

45. Edward Lear, "The Owl and the Pussy-Cat"

46. Rudyard Kipling, "The Glory of the Garden"

47. Robert Frost, "The Road Not Taken"

48. Rudyard Kipling, "The Way Through the Wood"

49. Wilfred Owen, "Anthem for a Doomed Youth"

50. Wendy Cope, "Bloody Men"

51. John Clare, "Emmonsail's Heath in Winter"

52. T.S. Eliot, "La Figlia Che Piange"

53. Philip Larkin, "The Whitsun Wedding"

54. Oscar Wilde, from "The Ballad of Reading Gaol"

55. Thomas Hood, "I Remember, I Remember"

56. Philip Larkin, "This Be the Verse"

57. D.H. Lawrence, "Snake"

58. Rupert Brooke, "The Great Lover"

59. Robert Burns, "A Red, Red Rose"

60. Louis MacNeice, "The Sunlight on the Garden"

61. Rupert Brooke, "The Old Vicarage, Grantchester"

62. John Betjeman, "Diary of a Church Mouse"

63. Walter de la Mare, "Silver"

64. Gerard Manley Hopkins, "Pied Beauty"

65. Louis MacNeice, "Prayer Before Birth"

66. T.S. Eliot, "Macavity: The Mystery Cat"

67. Thomas Hardy, "Afterwards"

68. G.K. Chesterton, "The Donkey"

69. Robert Browning, "My Last Duchess"

70. John Betjeman, "Christmas"

71. Ted Hughes, "The Thought-Fox"

72. T.S. Eliot, "Preludes"

73. George Herbert, "Love (III)"

74. Alfred Lord Tennyson, "The Charge of the Light Brigade"

75. John Clare, "I Am"

76. Francis Thompson, "The Hound of Heaven"

77. Christopher Marlowe, "The Passionate Shepherd to His Love"

78. W.B. Yeats, "The Song of Wandering Aengus"

79. George Gordon, Lord Byron, "She Walks in Beauty"

80. A.E. Housman, "Loveliest of Trees, the Cherry Now"

81. John Donne, "The Flea"

82. F.W. Harvey, "Ducks"

83. Philip Larkin, "An Arundel Tomb"

84. William Shakespeare, Sonnet 116 ("Let Me Not to the Marriage of True Minds")

85. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses"

86. Louis MacNeice, "Snow"

87. Roger McGough, "Let Me Die a Youngman's Death"

88. Thomas Hardy, "The Ruined Maid"

89. Hugo Williams, "Toilet"

90. Wilfred Owen, "Futility"

91. Edgar Allan Poe, "The Raven"

92. Robert Burns, "Tam O' Shanter"

93. Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Love's Philosophy"

94. H.W. Longfellow, from "The Song of Hiawatha" (Hiawatha's Wooing)

95. Gerard Manley Hopkins, "God's Grandeur"

96. Michael Rosen, "Chocolate Cake"

97. Leigh Hunt, "Jenny Kissed Me"

98. Seamus Heaney, "Blackberry-Picking"

99. William Wordsworth, from "The Prelude" (Childhood and School-Time)

100. Carol Ann Duffy, "Warming Her Pearls" That puts things in perspective. Reed beats three Louis MacNeice poems by at least 22 places, is only outshone by Eliot's "Prufrock," beats John Betjeman, is only three slots below Dylan Thomas's "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night," and even outranks his idol Thomas Hardy's best-known verses.

These selections were published in 1996 as The Nation's Favourite Poems (Amazon.co.uk), and spawned something of an industry in poetry anthologies. It'd be interesting to see, in the polls taken in the following years, whether Reed rose, or fell, or (God forbid) fell off, altogether.

|

1527. Rosenthal, M.L. "Experience and Poetry." Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review (New York), 17 October 1948, 28.

Rosenthal says Reed shares with Laurie Lee 'that unhappy vice of young intellectuals—a certain blandness of which the ever-simple irony is a symptom.'

|

An intriguing e-mail from a visitor appeared in my inbox this morning, regarding a cameo appearance of Reed in a newly-published book, London: City of Disappearances, edited by Iain Sinclair ( London Times review). The book is a collection of myths and mysteries of a London lost to time — stories of disappearing people, streets, pubs, and occupations — with contributions from J.G. Ballard, Marina Warner ( Guardian excerpt), Will Self (Penguin extract), Alan Moore, and Michael Moorcock.

Reed materializes in "Death of a Cleaner" by Richard Humphreys, 'a portrait of a mysterious character called Antony Ashburner.'

There is a mysterious and evocative poem by the Birmingham poet Henry Reed, called "Chrysothemis," which gives an insight into Ashburner's life in the Second City [i.e. Birmingham]. After his death I found a galley proof of the poem in his [Ashburner's] untidy flat at the wrong end of Ladbroke Grove. There was a dedication handwritten in ink: 'To Antony from Henry December 1942.' The poem is darkly Eliotic and casts light on an important if brief relationship...

The poem in question first appeared in John Lehmann's wartime anthology New Writing and Daylight (Winter 1942-1943), and is a long monologue in the voice of Chrysothemis, the passive sister of vengeful Orestes and Electra, children of Agamemnon and his murderous wife, Clytemnestra. Lengthy excerpts from the poem appear in Harvey Gross's metrical study from Sound and Form in Modern Poetry (1964).

Many thanks to John for alerting me to this! I can't wait to get a hold of a copy of City of Disappearances.

|

1526. Blunden, Edmund. "Poets and Poetry." Bookman, n.s., 1, no. 4 (July 1946): 14-15.

Edmund Blunden says Reed's Lessons of the War poems 'have captured something of the time-spirit and ambiguity of the recent war in a style of wit and deep feeling united.'

|

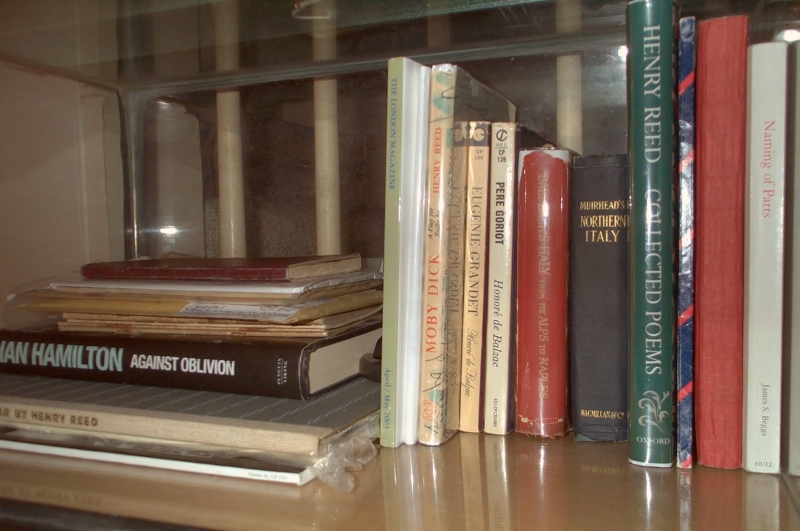

I've been considering cataloging my little Reed collection, using an online host like LibraryThing. The service allows you to post your collection online, tag your books, and browse other users' libraries with the same books. At present, however, LibraryThing pulls cover images from Amazon.com and other booksellers. Many of my Reed books are old and predate the ISBN system, so I expect my virtual bookshelf would look a little bare. Image uploading is a planned improvement ON!

The jackets from some of Reed's books are on the pictures page, but I'm still in the process of scanning the rest of my collection.

Other book covers I've scanned recently include: Eugenie Grandet, Pere Goriot, Three Plays by Ugo Betti, Hilda Tablet and Others, and The Streets of Pompeii.

Update: Tim Spalding of LibraryThing commented to say users can now submit cover images. Thanks, Tim!

|

1525. "Reed, Henry," Publishers Weekly, 152, no. 15 (11 October 1947), 1945.

A note on the publication of the American edition of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

I was surprised to find today, at "The Friends of the Library" used book sale, a striking number of sex books. Marital Aid-this, and Human-Sexuality-that. Titles that made me smile, then blush. The Pictoral Book of Sex. Sexercises. I'm the type who flips cautiously through coffeetable art books, lest the pages fall open at a particularly baudy nude by Titian or Botticelli.

When I first walked in, it was obvious the sale was a sort of barely-restrained chaos: a great square of tables, with people circling in both directions. As it was already an hour after opening, I circled left. Logic dictated that most of the herd would automatically turn right, and the less-picked over titles would be in the opposite direction.

There was no attempt at any sort of organization. Books were just randomly laid on the tables in three rows, spines up, with little piled ziggurats bookending the loose ends. At one point, a guy next to me asked if I knew how the books were organized. Alphabetically? By subject? I told him, "The books are arranged... horizontally." As empty spaces appeared in the rows, volunteers would heap more books into the holes like cordwood, from boxes under the tables.

The library's "Friends" get early admittance to these sorts of sales and as a result, by the time I arrived, there were great levees of books stacked against the walls, with slips of paper on top that read, "SOLD." Hoarders and bookdealers were breaking these piles down into boxes to be carted off to compulsive collections, storefronts, and eBay.

The books were a curious amalgam of donations which could not be reckoned within the scope of the library's collection, withdrawn titles, and great masses of texts which must of come directly out of some retiring professor's office. Whole tables of books on the ethics of euthanasia, machine learning, Jewish history, and plays and pulp novels in French.

There also smelled to be a higher-than-average number of Patchouli wearers present at the sale. Why do otherwise-attractive people insist on cloaking themselves in what amounts to the olfactory version of blasting their car stereo? Why are so many of them attracted by the lure of cheap books?

I spent a glorious, contented, three hours at the sale, making two complete passes over the tables, but didn't come away with any treasures. I found a copy of Perrine's Sound and Sense (which I probably already own a copy of). A theatre book of the script for Breaking the Code, by Hugh Whitemore, based on Hodges' book Alan Turning: The Enigma. A paperback on Australian literature, with a chapter on the Ern Malley poems.

My prize was a 1958 Grove Press edition of Three Plays by Ugo Betti, translated by Henry Reed. My heart leapt when I saw Reed's name in bold, white letters on the spine, hiding amidst an ancient pile of German literature in hardcover.

|

1524. Reed, Henry. Letters to Graham Greene, 1947-1948. Graham Greene Papers,

1807-1999. Boston College, John J. Burns Library, Archives and Manuscripts Department, MS.1995.003. Chestnut Hill, MA.

Letters from Reed to Graham Greene, including one from December, 1947 Reed included in an inscribed copy of A Map of Verona (1947).

|

Once upon a time, I had two fish: a pair of Bettas. Gandalf was a pale, blue-grey Betta who lived in a bowl in my office at work, and Saruman (it was the start of The Lord of the Rings movies. Hey, I didn't name them!), deep purple and crimson red, who had a magnificent, heated, ten-gallon tank all to himself on the bookcase at home. They were an impulse-purchase of a girlfriend and, along with the cat, rounded out our little menagerie.

As pets go, fish are low, low maintenance; and Bettas are tough as nails, but they don't last forever. By the time the LOTR trilogy had played out in theatres, both Gandalf and Saruman had gone to that big brandy snifter in the sky. For the fourth time in the fifteen years that I've owned it (rescued from my half-parents' Wunderkammer garage), my aquarium lay sterile and empty. Somewhere in the apartment is a box containing tiny, ceramic Greek ruins: Corinthian pillars and capitals.

When I described the sad sight of a barren, unused aquarium to a friend, lamenting the fact that I am, in fact, a dog person at heart, it was suggested that I use it instead to display books. Which are in no short supply around here.

So I rounded up my scattered collection of hardcopy Henry Reed-related material, and created a sort of memorial, print terrarium:

I own barely enough books on Reed to fill even half the aquarium. There's a couple of (relatively) recent journals: Cartographic Perspectives (Fall 2001), which contains an excellent article by Professor Adele Haft on Reed's use of maps and atlases in his poem " A Map of Verona," and The London Magazine (April/May 2003), with a reflective article by Anthony Howell on Reed's posthumously-published and lesser-known poetry. The rest are Reed's scant published works, and a few tangential and reference items. In my mania, I actually bought a couple of tourist guidebooks that Reed may have used during his several trips to Italy, containing the maps of streets through which his "thoughts have hovered and paced."

What's significant is what's missing: two volumes of Reed's radio plays, The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (BBC, 1971), and Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (BBC, 1971). The university library here in town has copies, so they've been low on my list of books to fill out my collection. But now, taking a good look at my sad, half-empty aquarium, I think I'm ready to make room for them. Maybe I'll add a "wishlist" to the blog, or even incorporate as a nonprofit the Friends of the Henry Reed Terrarium and set up a PayPal account to accept donations.

|

1523. Reed, Henry. "Simenon's Saga." Review of Pedigree by Georges Simenon, translated by Robert Baldick. Sunday Telegraph (London), 12 August 1962, 7.

Reed calls Pedigree a work for the "very serious Simenon student only," and disagrees with the translator's choice to put the novel into the past tense.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

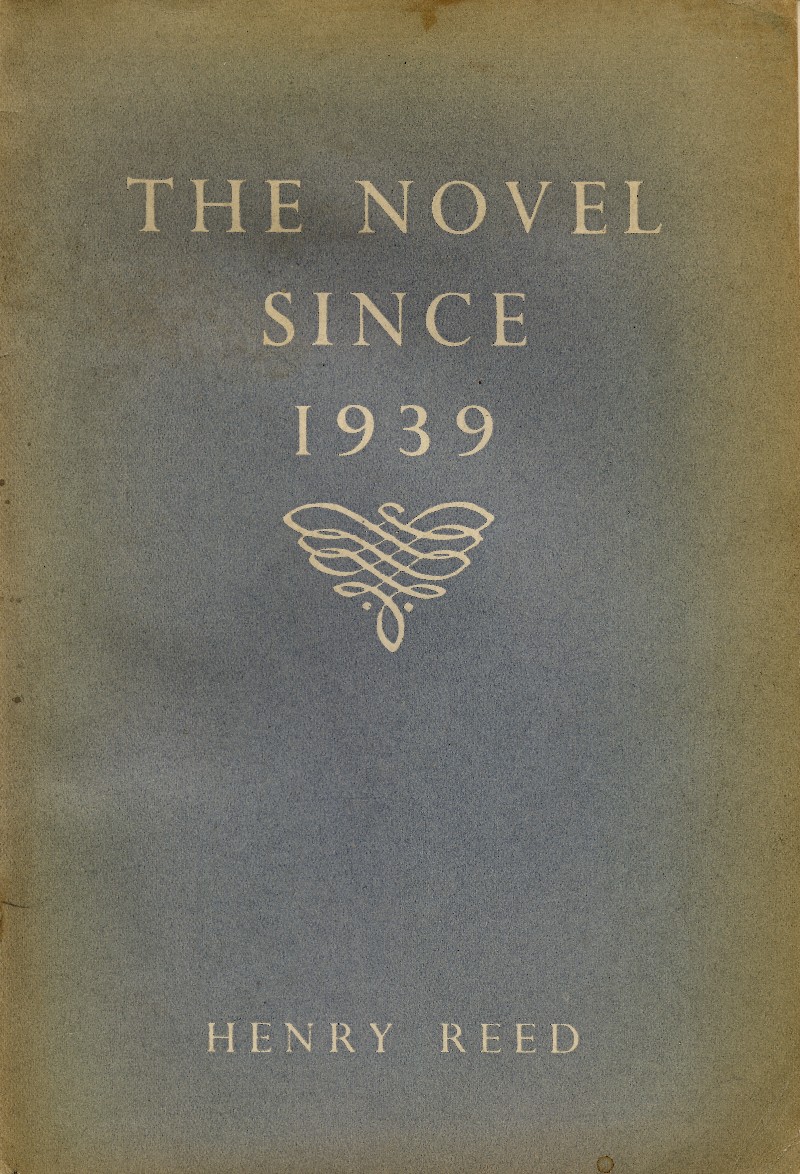

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|