|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Waugh"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

Here we find a letter from Evelyn Waugh to the novelist Nancy Mitford, written in 1946, regarding a review in the New Statesman and Nation by Henry Reed, of Mitford's novel, The Pursuit of Love.

Waugh is "irritated" by Reed's review, and by newspapers and journals and news, in general. Waugh doesn't know who Reed is, and even seems to think the byline on the review is a pseudonym (this despite Reed having reviewed Brideshead Revisited just the year previous). Waugh does somehow infer Reed's homosexuality on the basis of his review, but mistakes him for a lesbian.

This from the The Letters of Evelyn Waugh, edited by Mark Amory (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980), pp. 222-223: Piers Court. To NANCY MITFORD

4 February 1946

Dearest Nancy,

Since sending you a post-card today I purchased the New Statesman. I thought 'Reeds'1 review of your book egregiously silly both in praise & blame. I love all the Mitford childhood, as you know, but to single out the buffoon father while totally ignoring the unique children's underground movement is brutish. He calls your one false character 'a brilliant sketch'2. You know better than I how wrong he is about Fabrice. The review irritated me greatly. I wonder who it is who writes it. Plainly a homosexual; perhaps a Lesbian?

I looked at other pages of the paper & was astounded that you take it in. I read Eddie [Sackville-West] describing the use of the word 'brothel' on the wireless as 'a refreshing experience which spoke eloquently of the intelligence, sanity and good feeling of ordinary people'. I read 'Nothing can stop big Powers bullying their small neighbours if they wish to do so'. Last time I had the paper in the house it was boiling to attack Germany & Italy for no other reason. I read the wild beast saying that Mr Sutherland's painting 'rivals butterflies wings in delicacy.'3

The only thing that made any sense in the paper was a grovelling apology to a soldier they had insulted, but that had been dictated, presumably, by some intelligent solicitor.

How can you read it? It explains all that modern trash that encumbers your shop.Evelyn

1 Henry Reed (1914- ). Poet and BBC producer.

2 Talbot, the middle-class communist in The Pursuit of Love.

3 Raymond Mortimer was reviewing The Approach to Painting by Thomas Bodkin.

Here is the irritating review, from the New Statesman for February 2, 1946. Reed invokes several lessons from Joyce, including the best description of synecdoche ever written: "When a part so ptee does duty for the holos we soon grow to use of an allforabit."

NEW NOVELS

The Pursuit of Love. By Nancy Mitford, Hamish Hamilton. 8s. 6d.

Of Many Men. By James Aldridge. Michael Joseph. 8s. 6d.

The Crater's Edge. By Stephen Bagnall. Hamish Hamilton. 6s.

Everybody will remember that encouraging moment on page 108 of Finnigans Wake when, into the sleeping mind of H. C. Earwicker, as he toils over the difficulties of Anna's elusive letter, there flow these calming words: "Now, patience; and remember patience is the great thing, and above all things else we must avoid anything like being or becoming out of patience. A good plan used by worried business folk ... is to think of all the sinking fund of patience possessed in their conjoint names by both brothers Bruce ..." They are words I have often used to prop, in these bad days, my mind, as in my turn I have toiled through the pages of recent fiction. Patience is needed with all of the books listed above, even with Miss Mitford's The Pursuit of Love, which is rewardingly funny in many places. This is the least, and indeed the most, one can say of it. It begins extremely well with a picture of the children of an aristocratic family called Ratlett. Its early pages introduce, in Uncle Matthew and Captain Warbeck, two of the best comic figures in any modern novel, I cannot recall a funnier picture of the violent foreigner-hating patriarch than Uncle Matthew; his early morning foibles are beautifully recorded:He raged around the house, clanking cups of tea, shouting at his dogs, roaring at the housemaids, cracking the stock whips which he had brought back from Canada on the lawn with a noise greater than gun-fire, and all to the accompaniment of Galli Curci on his gramophone, an abnormally loud one with an enormous horn, through which would be shrieked "Una voce poco fa"—"The Mad-Song" from Lucia—"Lo, here the gen-tel lar-ha-hark"—and so on; played at top speed, thus rendering them even higher and more screeching than they ought to be.

... the spell was broken when he went all the way to Liverpool to hear. Galli Curci in person. The disillusionment caused by her appearance was so great that the records remained ever after silent, and were replaced by the deepest bass voices that money could buy. But, alas, though Uncle Matthew dodges in and out of the whole book, the later pages are given over to the affairs of one of his daughters; Linda. It is to her that title refers. The less successful episodes in her pursuit—her marriages with the banker Kroesig, and with Talbot, the middle-class Communist (a brilliant sketch)—are convincing enough; but at a moment of despair she is picked up by a French duke and installed as his mistress, and thenceforward the novel has the sentimental staginess of the late W. J. Locke. It has a certain characteristic contemporary wistfulness in its English admiration for the high-handed way in which upper-class French Catholics are presumed to fornicate, and one is interested to learn that the French are surprised if a woman does not express honte after a night with a lover. But it has also a dreadfully soft centre, and one is not surprised that Fabrice should eventually discover that what he feels for his enslaved mistress is the real right thing. They have both become unbelievable by the time Miss Mitford finally polishes them off; and in the later pages the irruptions of Uncle Matthew preparing to hold his house against the German invasion are a great relief:"I reckon," Uncle Matthew would say proudly, "that we shall be able to stop them for two hours—possibly three—before we are all killed. Not bad for such a little place." Of Many Men and The Crater's Edge each exemplify an extreme of mannerism which we may expect in war-fiction for many years to come. Of Many Men is the extremely hard-boiled type of war-novel, The Crater's Edge the extremely soft-boiled type. This is nowhere better illustrated than in the prose style of the two writers; in offering for the reader's judgment a little example of each, I am reminded of yet another of Joyce's persuasive remarks: "When a part so ptee does duty for the holos we soon grow to use of an allforabit." Here, for instance, is a characteristic passage from Mr. Aldridge:Wolfe entered Damascus with the French. The day after they arrived the Germans invaded Russia. Wolfe got the first Nairn bus that went to Baghdad and then he flew over the dead mountains to Teheran.

The Russians in Teheran said they were sorry that Wolfe had been in Finland, very sorry; but if he waited maybe he would get a visa. He waited a long time and the Red Army was still retreating to the Dnieper when he left Teheran. He could not get a visa.

The Germans were also in the Western Desert now. They had pushed the British back in to Egypt and had encircled and isolated the Australians at Tobruk. Wolfe went into Tobruk on one of the relief boats. And here we have Mr. Bagnall:If a girl loves someone at the age of sixteen for whom she has protested the madness of her love as a child of eight, even then he cannot be sure of her constancy, because, since nothing came of that protestation, nothing has flowered, and therefore nothing has had an opportunity to either flourish or die. Rather it has been in a state of perennial bud. So at first he made a noble decision of renunciation. Or perhaps it was not so much a decision he made as an attitude that he struck. Because he knew all the time he would not remain faithful to it. Yet he held it long enough to crystallise, or perhaps embalm, it in a sonnet of great-hearted finality and generous resolve. Generous himself at this point, Mr. Bagnall spares us the sonnet; but he spares us little else. His theme is one of those old, well-tried ones, which were never any good even when new: the theme of the dying man reliving the past. Not even vivid interludes can remove the distrust one has for a story whose end is also its beginning; and Mr. Bagnall's story has no vivid interludes. It is merely a series of lush reminiscences about the hero's four loves: his love for a ballet dancer (platonic), for a schooldays' friend ("without lust"), for a girl called Celia (with), and youthful Elizabeth (the real right thing once more) With its juicy, self-admiring prose, its purple passages, its recklessly misrelated participles and its lengthy commonplaces about the major problems of life, it is not an easy book to read.

The point of Mr. Aldridge's book lies quotation which prefaces it: "War is the shape of many men, those in the sun and those the shade; many hands clear the shade, but in truth they have only succeeded when the last shadow is gone." The book begins with its hero, emerging from the Civil War in Spain; during the next few years, in an unspecified capacity, he tours the second world war in Finland, Norway, Syria, Africa, Malaya, the Pacific, Italy and Germany; the facility with which he gets about will be seen in the passage I have quoted. After VE Day he announces his intention of returning to Spain, and the point of the book is made clear. Presumably if Mr. Aldridge had waited a month or two longer, we could have accompanied his hero to the bombing of Hiroshima (doubtless inside the actual aircraft) and to the meetings of Hirohito and MacArthur. The pity is that even when we have had the overwhelming course to accept Mr. Aldridge's style as a means of communication, he appears to have nothing to communicate beyond his central statement; the scenes we visit as we fly from one battle-front to another are stupefyingly machine-made. And though none will doubt the the truth of his epigraph, and few will doubt its application to Spain, it is a pretty bald gag to write a book about.Henry Reed

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

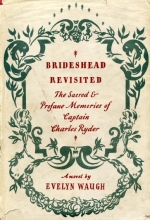

In scanning a full-text copy of Book Review Digest for 1946 at the Internet Archive, I noted several pieces of criticism by Henry Reed, including his rather famous review of Waugh's Brideshead Revisited for the New Statesman and Nation (23 June 1945, p. 408-409). Reed's review is often quoted by Waugh scholars as a piece of contemporary criticism, and was reprinted in Evelyn Waugh: The Critical Heritage (Martin Stannard, ed. London: Routledge, 1984).

NEW NOVELS Brideshead Revisited. By Evelyn Waugh. Chapman and Hall. 10s. 6d.

Household in Athens. By Glenway Wescott. Hamish Hamilton. 8s. 6d.

I Will be Good. By Hester W. Chapman. Secker and Warburg. 10s. 6d.

Serious implications have been present often enough in Mr. Evelyn Waugh's previous novels. The title of A Handful of Dust was significant; and certain excruciating moments in that book, as when the mother hears of her little boy's death, were threatening signs of a novelist whose powers were not easily to be ignored. Those powers find full expression in Brideshead Revisited, a novel flagrantly defective at times in theme and artistic sensibility, yet deeply moving in its theme and its design. It is as well to describe Waugh's faults at once; they recur constantly, both while one is reading him and while one is remembering him. They radiate almost wholly from an overpowering snobbishness: "How beautiful they are, the lordly ones," might well stand as an epigraph to Mr. Waugh's œuvre so far. A burden of respect for the peerage and for Eton, which those who belong to the former, or who hate been to the latter, seem able lightly to discard, weighs heavily upon him; and his satiric studies of the follies and cruelties of the posh have always been remarkable for the fact that their poshness has always seemed to the author more lovable than their silliness has seemed outrageous. It is a kind of snobbishness which finds one outlet in a special vulgarity of its own. There are several scenes in Brideshead Revisited where the narrator sets his own savoir faire against that of the lower characters—the scene in the Parisian restaurant with the colonial go-getter Rex, for example, or the pages satirising the transatlantic liner—and emerges as no less vulgar than his victims. It is as if a man should repeatedly point out to one that his bottom waistcoat-button is undone. This vulgarity goes very deep with Mr. Waugh; and it is not surprising that in embarking on his serious novel he should show an addiction to the purple.

The subjects of Brideshead Revisited are the inescapable watchfulness of God, and the contrast between the Christian (for Mr. Waugh, the Roman Catholic) sinner, and the other kind of sinner described in the cant term of our day as "pagan." Boldly, Mr. Waugh writes throughout from the point view of the pagan, which he, a convert to Roman Catholicism, has not forgotten; even more boldly he puts some of the most devout of Roman Catholicism among his least attractive characters. The book opens with a tale of romantic friendship at Oxford in the years following the first great war. Charles Ryder, the narrator, falls in love with Lord Sebastian Flyte, the beautiful son of Lord Marchmain; Marchmain himself, once a Catholic convert, is now an apostate; Sebastian is half-pagan. The Oxford passage, comic and romantic, is the most brilliant part of the book; nothing in the later part approaches it, save the last few pages of the story proper. The farce is of a high order; the picture of the narrator's father is a masterpiece of comedy; and the seeds of the later conflict are dextrously sown.

Sebastian is tormented by his mother, whom he cannot bear to be with. The mother is a mysterious and ambiguous figure, but not dissatisfying to the reader on that account. Sebastian's father has cut himself off from her and lives in Venice with a mistress. Like Sebastian, he flees from her, and it is perhaps not an over-interpretation to see here a suggestion that she represents some of the absolute exaction, difficult to face, of the Church. Symbolic or not, she is, in the story itself, patient, wonderful, cunning and unbearable; Sebastian cannot keep Ryder to himself and away from the family; and gradually he secedes from the relationship into drunkenness and vagabondage. Ten years later, Charles again meets Sebastian's sister, Julia, unhappily married to the barbarian Rex. The family charm works again, Charles falls in love with her, and is, in a curious phrase, "made free of her narrow loins" during a gale in mid-Atlantic. For two years their love survives happily; they are both about to be divorced in order to marry each other, when Julia feels "a twitch upon the thread"; she is reminded that she is living in a state of unchanging mortal sin, and cannot escape that consciousness; in the final pages, Charles is dismissed; we have already learned that Sebastian, far away in Morocco, has also felt the twitch upon the thread. The second part of the book falls far below the first; not only because for many pages we live in the dimensions of a gaudy novelette, enlivened, if at all, by the author's testiness at other people's bad taste, but because Julia is only a theme and not a person, whereas Sebastian has been both. Julia is alive only in her final speeches; and then simply because what she says is alive.

Underneath all the disfigurements, and never for long out of sight, there is in Brideshead Revisited a fine and brilliant book; its plan and a good deal of its execution are masterly, and it haunts one for days after one has read it. If one is reminded of François Mauriac it is not because Mr. Waugh's book is derivative, but for two other reasons. One remembers how much M. Mauriac can take for granted in his audience: Christian or agnostic, it knows what Catholicism is about. Mr. Waugh is in the far more difficult position of writing to an audience which in general is without that knowledge; he acquits himself convincingly, even to the pagan reader. Secondly, M. Mauriac reminds one of a lack in Mr. Waugh, for the great French novelist has sympathy with, and love for, the actual emotions of human beings. This sympathy and love are things no novelist can get along without; they are things which Mr. Waugh is still in the process of acquiring or reacquiring. A hard task; for they do not always survive religious conversion.

Household in Athens, Mr. Glenway Wescott's new book, is unusual among war-novels. Shock-tactics of technique, hysteria, over-loaded local colour, eager, unscrupulous cashing-in on the disasters of others: these are absent. It is not merely the intelligence and the watchful eye that have been engaged here. The heart is a dangerous necessity to the novelist; but it is, after all, his usual starting-point, however far away he gets from it. It is the first way of access which the author has to his characters. Mr. Wescott feels as deeply about his Greek family under the German occupation as the peace-time novelist feels about the creatures who build themselves up in his imagination and demand release. His four Greeks are thoroughly envisaged, the complexity of their plight, the slow, day-to-day horror, the mental dissolution and metamorphosis, the fantastic tricks played upon the mind bv physical decay, are desscribed with a realism of great calmness and strength. There is no local colour—a great relief. The Acropolis rises before us for a moment, but not for that purpose. There are no atrocities. It is a novel which explores its territory with great sincerity; it is a deliberately restricted territory, but there are moments when Mrs. Helianos's struggle with despair reaches out beyond the historical situation which provokes it. It is a profoundly moving book.

I Will be Good promises at first sight, and in its opening pages, to be a well-written, leisurely, escapist, comic novel; but into it one fails to escape. Nor is one meant to, though it might be possible to read the book as a romantic historical novel of immoral high-life in France in the eighteen-sixties, differing from others only by an unusual twist of fantasy. In point of fact, it has an almost Jamesian "idea" provoking it: a successful English lady novelist comes to live with a French family whom she well-meaningly, but insidiously and disastrously, persuades to behave like characters in one of her own romances. It is part of the great cleverness of the book that one is made to conjecture for oneself—and accurately, one believes—how the characters would have behaved if left to their real life. One knows, every time a wrong turning is taken, what the right alternative would have been. Between the amusing opening chapters and the beginning of the mischief there is an hiatus where one is out of step with the author's intention; as soon as this intention is clear the book is completely entertaining.Henry Reed

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|