Born in 1920, Dennis Joseph Enright taught abroad in Egypt, Japan, Thailand, and Singapore for many years, before returning to Britain in 1970. Enright belonged to The Movement, a loose confederation of poets who were allied against the excessive romanticism of the earlier poetry of the 1930s and '40s, preferring more sober, rational efforts. Enright's article, "The Significance of Poetry London," appeared in the first issue of The Critic, in the spring of 1947. It is an attack on what Enright felt was the magazine's indiscriminate inclusiveness, or "anti-critical" editorial policies. The full text of the article is not available online, but we can piece the gist of Enright's arguments together from different sources:

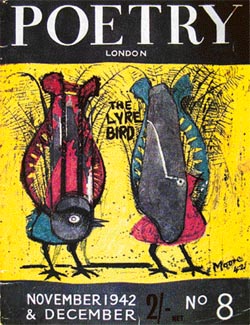

Since 1939 (in February of which year the magazine Poetry London was inaugurated) something, it would seem, has happened to poetry. To suggest another aspect of the problem we might vary the proposition and say that since 1939 very little of any permanent value has happened in poetry. Never before have poets sprung up so thickly, never before has publication (given the right contacts) been so easy—but hardly ever before has accepted and recognized work shown such a striking uniformity of weakness. The question before us now is: Has the latter fact any connexion with the former facts? Can it, even, be a case of effect and causes?

The Poetry of the Forties in Britain (1985), p. 277

Poetry is fast becoming a drug on the market; if an interesting poet emerges it is more than possible that his individual voice will be drowned in the general clamour; for every person who reads modern poetry without writing any, there are five who write poetry without ever reading any except their own and their friends'; the most influential verse magazine extant has consigned 'the critic' to an unpleasant death and openly disclaimed any principle other than catholicity; what little criticism is permitted has to remember that we are all poets, and poets ought to be one happy family, living together in a kind of pre-fabricated barn called an 'autonymous tradition.'

Civil Humor: The Poetry of Gavin Ewart (2003), p. 277, 15n

And my favorite bit:

There really ought to be a society for the prevention of cruelty to metaphors. These Poetry London poets flog their overworked metaphors mercilessly, force them into the most unnatural postures, pour gallon upon gallon of obscure pathos into them, until they burst—into bathos.

This last comes from Blake Morrison's book, The Movement: English Poetry and Fiction of the 1950s (Oxford University Press, 1980, p. 34), which also provides this tantalizing quote: 'Enright exempted from his criticism only one Poetry London contributor, Henry Reed, whose "Lessons of the War" he admired because "too modest, or too wise, to attempt to deal directly with War"' [sic].

I had previously scanned the wartime issues of Poetry London, looking for an appearance by Reed, but came up empty handed. I'm not sure if Morrison is correct in calling Reed a "contributor" to the magazine, or if he simply inferred it from Enright's praise. The university library's holdings are incomplete, and they have since removed the entire run to Rare Books for safekeeping.

Interestingly enough, in what appears to be a rebuttal in late 1947, Poetry London quotes Enright on Reed: 'The critic then proceeds to find Mr. Henry Reed's Lessons of the War "the best war poetry I have read."'

The Critic published only two issues before it was absorbed into Politics & Letters, making it rather difficult to find. In 1955, D.J. Enright edited (and contributed to) a collection of Movement poets, Poets of the 1950s, comprised of work by Kingsley Amis, Robert Conquest, Donald Davie, John Holloway, Elizabeth Jennings, Philip Larkin, and John Wain. Blake Morrison would later provide Enright's obituary for The Guardian, in 2003.