|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Gardner"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

Ages ago, back in 2007, I had a post about the critic and Eliot scholar, Dame Helen Gardner. Henry Reed had been a student of Gardner's at the University of Birmingham in the 1930s, and had introduced her to Eliot's poetry when he sent her a copy of "East Coker" in 1940. Gardner had credited Henry Reed in an article she wrote for the Summer, 1942 New Writing & Daylight on "The Recent Poetry of T.S. Eliot," saying that Reed had pointed out to her that some of the sea imagery in Eliot's "The Dry Salvages" may have come from the works of Herman Melville, and that 'the voice of Mr. Eliot's seabell is certainly like the sound of the Liverpool bell-buoy which Redburn heard as he sailed in to the Mersey.'

This last is, of course, entirely incorrect.

How do we know it's not true? Because Eliot tells us so. In her book, The Composition of Four Quartets (Oxford University Press, 1978), Gardner states:

After the publication of Little Gidding I wrote to Eliot, wishing to let him know how much these poems had meant to me, and told him that Mr. Lehmann had passed on his remarks. He replied saying my article had given him 'great pleasure' and went on Only two very small points occur to me. The first is that I have no such connection as you suggest with the house at Burnt Norton. It would not be worth while mentioning this except that it seemed to me to make a difference to the feeling that it should be merely a deserted house and garden wandered into without knowing anything whatsoever about the history of the house or who had lived in it. ... The other point is that I have never read or even heard of the book by Herman Melville.24 American critics and professors have been so excited about Melville in the last ten years or so that they naturally take for granted that everybody has read all of his books, but I imagine that bell buoys sound very much the same the world over. 24 I had suggested, with acknowledgement to Henry Reed, that a passage from Redburn lay behind the close of Part I of The Dry Salvages, Eliot mistakenly assumed Henry Reed was an American Professor of that name. [p. 37]

Silly Helen, foolhardy Henry. What did Eliot expatriate for, if not to avoid reading American literature? "Little Gidding" was published in December 1942, so Eliot's reply to Gardner must be circa 1943. The implied professor is Henry Reed (1808-54), Wordsworth's American editor.

Still, there is a tiny bit of redemption from Gardner's footnotes in The Composition of Four Quartets. Just a few pages further, attempting to attribute the sources for "Burnt Norton," she relays the following from Eliot:

In a letter to John Hayward, 5 August 1941, quoted in the heading to this chapter, Eliot mentioned three other sources: his own poem ' New Hampshire'; Kipling's story ' They', which he only recognized as having contributed to his poem when, five years later, he was re-reading Kipling for his anthology A Choice of Kipling's Verse; and a 'quotation from E.B. Browning'. Many years ago I suggested that 'the image of laughing hidden children may have been caught from Rudyard Kipling's story "They", since the children in that story are both "what might have been and what has been", appearing to those who have lost their children in the house of a blind woman who has never borne a child'. 28

28 The Art of T.S. Eliot (1949), 160. The suggestion was made to me by Henry Reed. [p. 39]

So we shall comfort ourselves with one Reed footnote to Eliot scholarship, instead of two.

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

What makes for a best-selling memoir? Celebrity confessions. Confessions like Mackenzie Phillips reveals in her book, High on Arrival, that she had been involved in an incestuous relationship with her father. Such as Andre Agassi confessing that his trademark long hair was actually a wig and that he used crystal meth, in his forthcoming autobiography, Open.

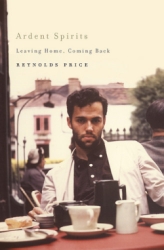

I confess, I don't actually know what bombshells Reynolds Price may drop in his recent memoir, Ardent Spirits: Leaving Home, Coming Back (New York: Scribner, 2009). I have my library's copy here, on my crowded coffee table. I haven't read it, yet. Not all of it. But I have found a pertinent piece of juicy gossip.

Reynolds Price has been a Professor of English at Duke University for fifty years, and is an award-winning author of fourteen novels. Ardent Spirits is his third memoir, covering his three years as a Rhodes Scholar at Merton College, Oxford, beginning in 1955, until after his return to North Carolina in 1958, when he begins his teaching and writing careers. Price has never written openly about his sexuality until this most recent volume, where he refers to himself (and others) as "queer."

While at Oxford, Mr. Price made the acquaintance of such literary luminaries as W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Cyril Connolly, and Helen Gardner—then a fellow at St. Hilda's College. Price attended Gardner's lectures on the metaphysical poets, and her seminar in textual editing, and eventually she would sponsor his thesis on Milton's use of the Chorus in Samson Agonistes.

This is where I get to the juicy part, the bombshell. In the mid-1930s, Henry Reed had been a student of Gardner's while he was doing his graduate studies at the University of Birmingham. Price writes:

Helen Gardner knew her subjects exhaustively and conveyed her mastery in lucid, but never condescending, lectures—one of the rarest of academic skills. She'd nonetheless been subjected to many of the disappointments of a brilliant woman in what was then distinctly a man's world. Stephen Spender would eventually tell me that he'd heard from W.H. Auden that, when she held a job at the University of Birmingham, Gardner fell in love with the poet Henry Reed. Reed, however, was queer; and Gardner's encounter with that reality led to a psychotic breakdown. In the absence of a good biography, I can't vouch for Auden's story; but it has a likely sound, especially since I slowly became aware of her reservations about many of her male colleagues at Oxford, and more than once I heard her cast strong aspersions at Auden and his friends. As her pupil, of course I was fascinated to hear of those possible early troubles in her life. [p. 43]

Wow. This is not the sort of literary footnote I usually get to post. Still, I'm inclined to say Mr. Price's rumor is simple hearsay—an exaggeration as a result of a game of Telephone among poets—considering that Reed sent Gardner a copy of Eliot's "East Coker" in the spring of 1940, and that Gardner, in 1942, credited Reed with a point relating to "The Dry Salvages" (see previously). That hardly sounds like the aftermath of an unrequited love affair and mental breakdown.

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

Dame Helen Louise Gardner (1908-1986) was a professor, critic, and editor, but above all, she was a scholar. Her work on Shakespeare, Milton, Donne, Eliot, and religious verse is still greatly respected, and earned her honorary doctorates from London, Harvard, Yale, and Cambridge Universities, among others. She took an M.A. at St. Hilda's College, Oxford in 1935, and returned to the school in 1941, teaching at Oxford until 1975. She was made a DBE in 1967.

Helen Gardner began her career as an assistant lecturer at the University of Birmingham in 1930. She took a position at the University of London in 1931, but returned to Birmingham as a lecturer in English from 1934-41. In her book, In Defense of the Imagination (Harvard University Press, 1982), Gardner recalls receiving a packet in the mail in the spring of 1940, in the midst of the "phoney war." Inside was the Easter Number of the New English Weekly, which contained a new poem by T.S. Eliot. 'I found myself reading a poem that offered no easy comfort, but only the true comfort of hearing a voice speaking out of the darkness without cynicism and without despair.' The poem would inspire her to recommend Eliot as wartime reading during a series of public lectures that summer. The poem was "East Coker," the second of his Four Quartets, and it had been sent to Gardner by none other than Henry Reed, who had been a graduate student at the University of Birmingham from 1934-36.

I came across a small homage to Reed today, in an article Gardner wrote called "The Recent Poetry of T.S. Eliot" ( New Writing and Daylight, Summer 1942). A note to her discussion of "The Dry Salvages" expresses her gratitude:

Mr. Henry Reed, to whom I am indebted for much sympathetic and illuminating criticism, and without whose encouragement this article would not have been written, has pointed out to me a passage in Herman Melville's 'Redburn,' from which some of the sea imagery of 'The Dry Salvages' may derive. The voice of Mr. Eliot's seabell is certainly very like the sound of the Liverpool bell-buoy which Redburn heard as he sailed into the Mersey.

Here is the relevant section from Melville's sea-faring novel Redburn: His First Voyage (1849), concerning the bell-buoy:

After running till about midnight, we "hove-to" near the mouth of the Mersey; and next morning, before day-break, took the first of the flood; and with a fair wind, stood into the river; which, at its mouth, is quite an arm of the sea. Presently, in the misty twilight, we passed immense buoys, and caught sight of distant objects on shore, vague and shadowy shapes, like Ossian's ghosts.

As I stood leaning over the side, and trying to summon up some image of Liverpool, to see how the reality would answer to my conceit; and while the fog, and mist, and gray dawn were investing every thing with a mysterious interest, I was startled by the doleful, dismal sound of a great bell, whose slow intermitting tolling seemed in unison with the solemn roll of the billows. I thought I had never heard so boding a sound; a sound that seemed to speak of judgment and the resurrection, like belfry-mouthed Paul of Tarsus.

It was not in the direction of the shore; but seemed to come out of the vaults of the sea, and out of the mist and fog.

Who was dead, and what could it be?

I soon learned from my shipmates, that this was the famous Bett-Buoy, which is precisely what its name implies; and tolls fast or slow, according to the agitation of the waves. In a calm, it is dumb; in a moderate breeze, it tolls gently; but in a gale, it is an alarum like the tocsin, warning all mariners to flee. But it seemed fuller of dirges for the past, than of monitions for the future; and no one can give ear to it, without thinking of the sailors who sleep far beneath it at the bottom of the deep. Melville's "Bett" is a variant of "beat," a rhythm or measure. Compare this with Eliot's sea-bell in " The Dry Salvages" (1941):

The sea howl

And the sea yelp, are different voices

Often together heard: the whine in the rigging,

The menace and caress of wave that breaks on water,

The distant rote in the granite teeth,

And the wailing warning from the approaching headland

Are all sea voices, and the heaving groaner

Rounded homewards, and the seagull:

The tolling bell

Measures time not our time, rung by the unhurried

Ground swell, a time

Older than the time of chronometers, older

Than time counted by anxious worried women

Lying awake, calculating the future,

Trying to unweave, unwind, unravel

And piece together the past and the future,

Between midnight and dawn, when the past is all deception,

The future futureless, before the morning watch

When time stops and time is never ending;

And the ground swell, that is and was from the beginning,

Clangs

The bell. Reed's suggestion makes for a strong argument, and Gardner says in her article that "The Dry Salvages" 'marries most absolutely metaphor and idea. The sea imagery runs through it with a freedom and a power hardly equalled in Mr. Eliot's other poetry.'

|

1539. Trewin, J.C. "Dead and Alive." Listener 50, no. 1281 (17 Sepetember 1953): 479-480.

Trewin's review of the BBC Third Programme premiere of Reed's play, A Very Great Man Indeed.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|