Sitting here in the icy-cold undergraduate library, however, I noticed there were at least two items on my list within cat-swinging distance. One was a 1948 book review of The New British Poets, which only mentions Reed lumped along with Patrick Evans, G.S. Fraser, Wrey Gardiner, Sean Jennett, Vernon Watkins, and Laurie Lee. (Also, I may be the only person in town who actually bothers to pay for their microfilm photocopies, judging by the poor, flustered students working the Circulation Desk.)

The second, however, was a review of Elizabeth Bowen's A Time in Rome (1960), critiqued by the consummate Italophile himself, Henry Reed.

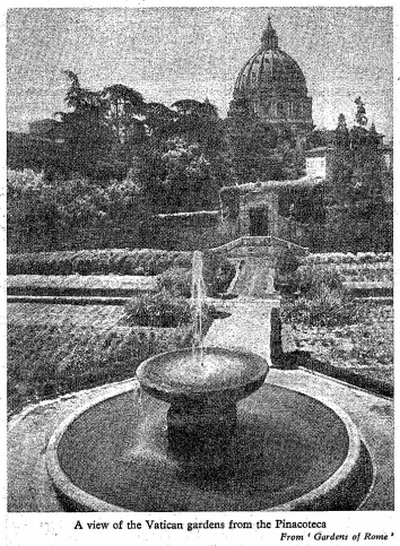

The photograph above is from Gardens of Rome, by Gabriel Faure (1960). Here's a more recent shot (Flickr) from (almost) the same perspective. The "Pinacoteca" is the Vatican art museum.

The review appears in The Listener from January 12, 1961, and is entitled "Rome: 'Time's Central City'" (.pdf). Reed seems to have thoroughly enjoyed it. He may have been slightly biased owing to his friendship with Bowen, but when it came to Italy, I don't believe Reed would have pulled any punches. When have you ever seen such dexterity with a semi-colon?

[A Time in Rome] is the exact antithesis of most travel books. It is magnificently unillustrated, for one thing; for another, its author is explicitly anxious not to be of help to any other visitor. It is essentially a book to be read away from Rome, not in it. It has further negative virtues; there is nothing about the unremitting winsomeness of the natives; there are none of those maudlin conversation-pieces with which even the sincerest are wont to bedizen their reminiscences; and none of the authoritative inclusiveness of the dug-in expatriate ('Gino smiled, as no one outside Florence knows how to smile: and all Florentines of course have perfect teeth'). Miss Bowen sees selectively, and with adequate passion; she is not an indiscriminate watcher; she is not a camera (nor, in point of fact, was Mr. Isherwood). If she tells you anything about Rome, she gives you a recognizable part of herself with it...[.]

'Gradually,' Reed says later, 'one begins to see that this book, like all Miss Bowen's work, is about a form of love.' At no point does he take to task any of Bowen's ideas or findings about Rome. Indeed, her Rome, he says, 'is perfectly created, and separate now from the city itself.'