New Novels

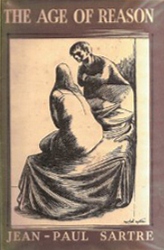

The Age of Reason. By Jean-Paul Sartre.

Translated by Eric Sutton. Hamish Hamilton. 10s.

Pascual Duarte's Family. By Camilo J. Cela.

Eyre and Spottiswoode. 7s. 6d.

The Leaping Lad. By Sid Chaplin.

Phoenix House. 8s. 6d.

M. SARTRE is primarily a brilliant artist. He is secondarily a philosopher, one of the leaders of a more or less new school of thought. It is therefore a great pity that in England we should have read so much about his philosophical ideas before we have had much chance of reading his stories and plays; and it is probably a further pity that his ideas should for the most part have been first expounded by antagonistic critics. His plays, 'Les Mouches', 'Huis-Clos' and 'La Putain: Respectueuse', need nothing in the way of exposition; they make their points unaided, and their points are clear ones. With The Age of Reason I feel far less sure; it is the first volume of a trilogy called 'Les Chemins de la Liberté', and though it is a book of quite extraordinary power it cannot be thought of very easily as a work by itself, since at the end of volume one, the reader is likely to be left still baffled by M. Sartre's theme, and by his terminology. The semantic of abstract nouns is almost always so eroded (as Professor Hogben would say) that they need continual re-definition. And I am far from certain what M. Sartre means either by freedom or by reason. I have uneasily assumed from the story itself, and from things I have picked up here and there, that Mathieu, the hero of the book, who is questing for freedom, is out to attain a state of mind and a condition of will where he will be free to act without being influenced by the image he creates in the minds of others. As a child he has vowed to himself: 'I will be free'. At the end of the first volume we find him saying to himself that he has attained the age of reason, and the meaning of this is, so far, even less clear; he means in one sense that his adolescence is over; but one is perplexed by the fact that his attainment of the age of reason, whatever it be, is principally caused by an act performed by someone else. This is brought about as follows.The one bit of personal information we can glean from this review is the mention of Professor Lancelot Hogben. Hogben was an experimental zoologist whose varied career included two professorships at the University of Birmingham from 1941-1961. Reed must have known him, or known of him, from his time there. Hogben seems to have cut quite a figure across several fields of study, was quite well known, and the two shared Socialist leanings. Hogben's books on language and semantics—which surely would have greatly interested Reed—were not published until the 1950s and 60s, but obviously he was expounding on such topics much, much earlier.

Mathieu, a lecturer in philosophy and the central figure of a small group of people in Paris, is told by Marcelle, his mistress, that she is pregnant. He assumes that an abortion is necessary, and he sets out to get the money for it. His efforts to raise four thousand francs are the principal strand in the book. There are other things going on at the same time: they mainly concern two young friends of Mathieu, his pupil Boris Seguine, and Ivich, who is Boris's sister. There is a no longer young cabaret singer called Lola, who is feverishly in love with Boris. Mathieu himself, rather to his own surprise, at a particular point during the forty-eight hours covered by the book, falls suddenly and fruitlessly in love with Ivich, whose own sexual appetites are, up to now, uncertainly directed. Mathieu continues his quest for money; within forty hours or so, having exhausted all possible sources, he steals from Lola. She thinks the theft has been committed by Boris, whom she knows to practise theft in a small way from bookshops and the like. By this time we have already seen a good deal of another character, Daniel, a homosexual, and a friend of Marcelle. Marcelle, discovering that Mathieu is no longer in love with her, has told him to go. He has by now discovered that she wants the baby and has offered to marry her. Just as Lola is telling Mathieu that she is charging Boris with theft, Daniel enters Mathieu's apartment and announces that he is going to marry Marcelle. We are left at this point to await the second volume, and, if our curiosity has been aroused, to wonder what will now happen to Lola and Boris, to Ivich, who has failed in her examinations and must return to her hated home in Laon, to the unpromising marriage of Marcelle and Daniel, and to Mathieu and his reasoning, reasoned or reasonable age.

The story may be called sordid, morbid,) and 'unrepresentative', though M. Sartre does not, I think, make it these things. Extended comment on it can scarcely be made at this stage; but there are some things that immediately occur to one. I do not know how consequent or inconsequent M. Sartre's version of existentialism is; but it appears to provide a most potent atmosphere and background, which would, I believe, be apprehensible even to a reader who had picked up none of the relevant jargon. It is not necessary to have mugged up the subject in order to see the strange new perspectives behind M. Sartre's novel; the ominous background is there, and it is possible to be much moved by it. It reminds me of those floorboard landscapes of Chirico and some of the surrealists: those long parallel lines receding into the distance and ending, sharply at a void of empty and ominous sky. Over such a floor and oppressed by the same anguished and thundery air, the tatty characters of M. Sartre's novel move. It seems to me as acceptable and convincing a mise-en-scène as any other, if the human condition is your subject.

The early chapters of the book at once indicate a master, perhaps a great one; certainly an authoritative technician and stylist who also has his characters, and their actions, extremely well taped. That void on the horizon, towards which his characters painfully glance from time to time, is poetically 'touched in'. The climaxes and turns in the story are brilliantly timed, the folds of the narrative adroitly set. There is a wonderful feeling of suspense about the book. There is also a certain monotony, and at a first reading some of the conversations seem over-long; I wonder also if it is entirely well-judged to set so much of the book in bedrooms and nightclubs. But its monotony seems to me the acceptable monotony of an epic.

Pascual Duarte's Family is a story about a murderer, told by the murderer himself; the book would probably fail if we were not on the murderer's side, for it is superficially a story of fantastic squalor, and at times steps perilously near the point where the unbearable becomes the farcical. But the murderer is a man who strives to be good and his sister's lover and his own mother, both of whom he murders, are irremediably bad. The nets of circumstance close in on him from every side, and there is a tragic inevitability about his disastrous acts; though since the facts of his story are so violent and brutal, the general poetic quality of the story is probably incommunicable by reviewer to reader; the reader may doubt that the character of a matricide (who later, it is hinted, commits a common political murder) can evoke pity. But the priest's verdict on Pascual is true: he 'could be recognised when one probed to the depths of his soul as not other than a poor tame sheep, harassed and terrified by life itself'. Señor Cela's book is subtle and disquieting, and I do not remember that its story has ever been used before.

The Leaping Lad is a collection of short stories, all set in a mining-valley in Durham. This, forgivably but unfortunately, will put most readers off. Those whom it doesn't will find that, despite limitations of theme and setting, Mr. Chaplin's stories usually are stories with a beginning, a middle, and an end; and rarely mere sketches. There is also a vein of gaiety and exhilaration running through a good many of them, which crops up as deliciously as the outbursts of fresh, green countryside in the sombre landscape which is Mr. Chaplin's native heath. 'Rooms', 'The Pigeon-Cree', 'The Shaft' and 'The Unwanted' are particularly good stories; while the story called 'And the Third Day' promises well for the time when Mr. Chaplin sets out on a longer flight.Henry Reed