Henry Reed, of course, famously adapted Moby-Dick into a play for the BBC's Third Programme (starring Sir Ralph Richardson as Ahab), first broadcast on January 26, 1947. A second production was organized and broadcast on Radio 4 in 1979.

Reed also reviewed a new edition of Melville's Billy Budd for the "Books in General" column in the New Statesman and Nation on May 31, 1947. He had as much to say about Moby-Dick as he did for Billy Budd. Spoiler alert! If you haven't read it:

BOOKS IN GENERAL

To discover and to read, in the midst of a batch of contemporary novels, Herman Melville's last—and hitherto all but improcurable—story, Billy Budd, Foretopman* is to find oneself faced with a dazzling revelation of, how many virtues modern fiction has lost or discarded. Billy Budd is, in the first place, a good story, a "plain tale," or so it appears; it is well written, and the uncertainties of its manuscript text do not greatly matter; it has a hero and a villain who are carefully designed to dramatise the extremes of goodness and badness. And more striking than anything else to the reader of to-day are its discursive comments on character, the generalisations about psychology evoked by the development of the story itself. One cannot doubt that in modern novelists the capacity for moral commentary still exists; but it is a capacity they more and more tend to suppress. When Melville blesses one of his characters with "natural depravity," it seems to him perfectly reasonable to enlarge on the implications of this:The Moby-Dick "Big Read" runs through January, 2013.

Not many are the examples of this depravity which the gallows and jail supply. At any rate, for notable instances—since these have no vulgar alloy of the brute in them, but invariably are dominated by intellectuality—one must go elsewhere. Civilisation, especially if of the austere sort, is auspicious to it. It folds itself in the mantle of respectability. It has its certain negative virtues serving as silent auxiliaries. It is not going too far to say that it is without vices or small sins. There is a phenomenal pride in it that excludes them from anything... mercenary or avaricious... In short, the depravity here meant partakes nothing of the sordid or sensual. It is serious but free from acerbity. Though no flatterer of mankind, it never speaks ill of it.At first Billy Budd seems a curious book to think of Melville writing; but much criticism has prepared one for its late-Shakespearean calm. In the crowding tumult of Moby Dick and the neurotic fervour of Pierre, Melville seems to have burned himself out; or, if the fire remained, it was damped down by popular neglect or censure or incomprehension. In the Oxford History of the United States, Professor Morison of Harvard says that "not until 1851 did a distinctive American literature, original both in form and content, emerge with Moby Dick"; and it is rarely that a literary landmark is detected until it has been left a good way behind. Wretched and perplexed Melville struggled on, as we know, with a few other novels and short stories, and then quietly abandoned prose writing. Almost forty years after Moby Dick, and within a year or so of his death, he produced Billy Budd.

But the thing which in eminent instances signalises so exceptional a nature is this: though the man's even temper and discreet bearing would seem to intimate a mind peculiarly subject to the law of reason, not the less in his soul's recesses he would seem to riot in complete exemption from that law having apparently little to do with reason further than to employ it as an ambidexter implement for effecting the irrational. That is to say: toward the accomplishment of an aim which in wantonness of malignity would seem to partake of the insane, he will direct a cool judgment sagacious and sound.

These men are true madmen, and of the most dangerous sort, for their lunacy is not continuous, but occasional; evoked by some special object; it is secretive and self-contained, so that when most active it is to the average mind not distinguished from sanity, and for the reason above suggested that whatever its aim may be, and the aim is never disclosed, the method and the outward proceeding is always perfectly rational.

Now something such was Claggart...

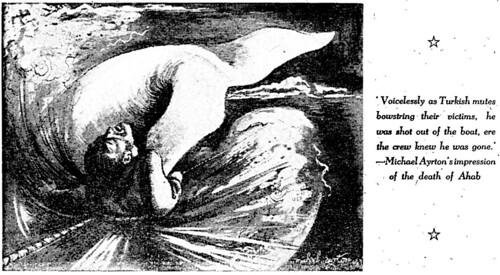

In style and mood it is as far from Moby Dick as it could be. In the earlier book one remembers, side by side with its exact realism, rhapsody also, and its fine, rhetorical, probable conversations. There is neither rhetoric nor rhapsody in Billy Budd. And in Moby Dick Melville is continually forcing you to look, beyond the lives of his characters, at Life itself. For Melville, as for Ahab, the battered Pequod is an ambiguous vessel: its mixed crew are "an Anacharsis Clootz deputation from all the isles of the sea, and all the ends of the earth, accompanying Old Ahab in the Pequod to lay the world's grievances before that bar from which not very many of them come back." It is "an audacious, immitigable and supernatural revenge" that Ahab intends in his pursuit of the white whale.

...All that most maddens and torments; all that stirs tip the lees of things; all truth with malice in it; all that cracks the sinews and cakes the brain; all the subtle demonisms of life and thought; all evil, to crazy Ahab, were visibly personified, and made practically assailable in Moby Dick. He piled upon the whale's white hump the sim of all the general rage and hate felt by his whole race from Adam down.To Ahab "all visible objects are but as pasteboard masks." And he infects the crew with his unearthly feeling for Moby Dick in a way that Ishmael, the story-teller, hesitates to define:

What the White Whale was to them, or how to their unconscious understandings, also, in some dim, unsuspected way, he might have seemed the great gliding demon of the seas of life—all this to explain would be to dive deeper than Ishmael can go.But he does at once go deeper; and the chapter on whiteness is perhaps the "deepest" thing in the book. It is a chapter about the beauty and the terror of white objects, animate and inanimate: "and of all these things the Albino whale was the symbol. Wonder ye, then, at the fiery hunt?"

By these, and by many other touches, Melville accretes to his realistic story an imprecise and terrible other story. The actual whale is not, he assures us, an allegorical creature he has made up himself. The whale itself is real enough; it is in the nature of Melville to see an object or creature accurately before the object takes on an ambiguous cast. He sees the whales' nursery, can mean to him:

And thus, though surrounded by circle upon circle of consternation and affrights, did these inscrutable creatures at the centre freely and fearlessly indulge in all peaceful concernments; yea, serenely revelled in dalliance and delight. But even so, amid the tornadoed Atlantic of my being, do I myself still for ever centrally disport in mute calm; and while ponderous planets of unwaning woe revolve round me, deep down and deep inland there I still bathe me in eternal mildness of joy.Object first; simile, some distance after. Melville's mind is free from the allegorical impulse which takes a spiritual theme and impresses objects into the illumination of it. This distinction between allegory and symbolism must not be forgotten, since it is always there. In symbolism the real object is seen first; from it, to adopt a phrase of Mr. T. S. Eliot, a "purpose breaks." This happens continually in Melville; and it is worth recalling that his great creative period coincided with that of Poe, to whom the French symbolist poets were always confessing their debt.

From Billy Budd also, when the tale is completed, a purpose breaks; a simple one, emerging with deceptive quietness. In this tale Melville, at the end of his life, is giving expression to a feeling he has perhaps not before acknowledged or understood. Once more, he comes to understand it by way of real objects and people. It is as if retired within himself, and searching the darkness of experience that lies behind and before him, he draws up from the shadows a perfect image of uncontaminated beauty, nobility and courtesy. We know who provided that image: it was Melville's friend of earlier days, Jack Chase; and it is to him that the new book is dedicated: "To Jack Chase, Englishman, wherever that great heart may now be here on earth or harboured in Paradise." Chase had been captain of the maintop in the frigate United States, in which Melville had served in 1843. He had shone like a bright light in the ugly world that Melville describes in White Jacket; idealised a little, he now appears as Billy Budd. The action is moved back to the days of Napoleonic wars, shortly after the Mutiny at the Nore.

There is little or none of the "transcendental" Melville in the actual language of the book. It is true that the Anacharsis Clootz deputation is once more referred to; and the free merchant vessel from which Billy is impressed into the Navy is called the Rights of Man. But this is a mere glimpse of the book's outer rind; we do not touch that half-whimsical quality again till the very end, when we hear the name of another ship. Billy is forced to serve in a man-of-war. He is what in those days was called a Handsome Sailor. He has a beauty that is praised and adored by the generality of men—and he is not, it may be urgently stated, a pansy. But Billy's grace, as is the way of grace, evokes also from one point an overwhelming malignity. There is among the crew an official of some power called Claggart, whom Melville seems to develop from, the villainous Jackson of his early autobiographical novel Redburn. Claggart is not unaffected by the beauty of Billy's form and character. He perceives it, one might say, much as Iago perceives that of Cassio:

If Cassio do remain,Claggart, ostensibly affable towards Billy, decides in his heart that he must be done away with. The discernment of the ways and means of such a hate is one of Melville's many profound intuitions; I do not doubt that he could have pursued the origins of such a passion further, for his prose and his poetry abound in astonishingly prophetic hints about the reaches of the unconscious. But none are given here. At school one sometimes dimly recognised something ineffably horrible when one, saw a perverted schoolmaster bullying an angelic-looking boy; Melville allows us dimly to recognise a perversion of much the same kind here. Claggart fabricates against Billy a charge of incitement to mutiny, and reports him to Vere, the captain, a man extreme nobility and perception. Vere is dubious of the charge, and sends for Billy. Billy is afflicted with a stammer—his one defect. When confronted with the charge he cannot speak; he answers Claggart in the only way he knows; he strikes him with all his force, and Claggart falls dead. Vere's sympathies are wholly with Billy; but a trial is inevitable; so are the verdict and the punishment. It is war-time; and the question of mutiny is a real thing, not to be treated lightly. Vere asks what is truth; but dare not stay for an answer. At dawn next day Billy is hanged at the yard-end.

He hath a daily beauty in his life

That makes me ugly.

As a character Billy meant a little more to Melville than could be expressed in prose. Billy Budd ends with a rather touching unaccomplished effort to get into Billy's impenetrable mind by way of verse:

But me, they'll lay me in hammock, drop me deepBut the story as a whole remains more important than its parts or its separate characters. If we have any doubts about what it "means" to Melville, he puts them to rest by a few more or those touches which, for want of a proper word, I have called half-whimsical Billy dies; "and, ascending, took the full rose of the dawn." The noble Captain Vere is felled shortly after by a musket-ball from a ship which has been re-named the Athéiste. And for years afterwards the spar from which Billy has hanged is kept trace of by the crew; to them, later, "a chip of it was as a piece of the Cross." ...The creator of that and the white whale was to cherish his "ambiguities" to the end.

Fathoms down, fathoms down, how I'll dream fast asleep.

I feel it stealing now. Sentry, are you there?

Just ease these darbies at the wrist,

And roll me over fair,

I am sleepy, and the oozy weeds about me twist.Henry Reed

* Billy Budd. By Herman Melville. Introduction by William Plomer. Lehmann. 5s.