|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Brooke"

|

|

|

21.12.2024

|

[This letter to the editor, by the poet and critic Henry Reed, is part of an exchange between readers of The Listener from early 1945, in response to a series of articles Reed had written on contemporary war poets. It's interesting to note that Reed's address is given as "Bletchley", Milton Keynes, since at this time he was still stationed at the Bletchley Park estate, working for the codebreaking effort as a translator of Italian and Japanese.]

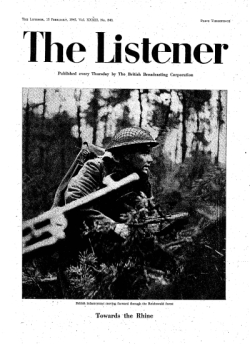

The Listener, 15 February, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 840 (p. 185) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

The literary critic must concern himself more with the achievement of poets than with their renown, and the popularity or otherwise of the poets I wrote about is not my business. It is always deplorable that poets who are gifted, sincere and hard-working should be ignored or disparaged merely because their work is not always easy to grasp; but it will, I think, be a long time before one can hope for a disappearance of that traditional attitude which finds expression in the satirical second paragraph of Mr. Richards' letter: 'If we admit that people, however they may respect contemporary poets, do not quote them, then what Mr. Reed means by poetry and what it means to the homme moyen esthétique are two entirely different and distinct things'. Between the protasis and the apodosis of this statement there is no obvious connection; but I sense from the tone what Mr. Richards believes: that modern poetry—probably all of it—is obscure, impenetrable, esoteric, and unlovely. I do not agree with him: we can merely state our tastes. But if by the homme moyen esthétique he means the average man who takes an interest in art—the man who, for example, takes the trouble to go to W.E.A. classes, or to read regularly and seriously by himself—then I know that he very much underestimates that man's tolerance, patience and curiosity. Mr. Richards lacks these qualities, and is wrong to put himself beside the homme moyen esthétique. He is the homme moyen philistin; and he is proud of it.

It is more profitable to discuss Mr. Richards' first paragraph. He is right in assuming that Rupert Brooke achieved far greater popularity than any poet of today. This was not, however, due to any particular poetic merit; Brooke's talents were, in fact, of the slightest. He achieved his unparalleled popularity, I believe, simply because he contrived at an appropriate moment to falsify the nature of war in a way that the public found palatable. He himself is not to be blamed for this; had he lived, he might have regretted his five war-sonnets (and had he lived, he would probably never have been so famous). For they show a defect of imagination which in a poet is serious to the point of catastrophe. And Brooke saw very little of the war itself, and nothing at all of the long-term horror which might have filled the gap his imagination failed to fill. He wrote in enthusiastic ignorance; death in battle appeared lovely; there was no suggestion that war might be a tragedy. This was all highly consolatory to those whose task it was to keep the home fires burning. He was a poet for the thoughtless; and there is no fundamental difference between his war-poetry and the present-day song beginning 'There'll always be an England'.

The poets who saw what war was really like, who saw it for a long time, and who unflinchingly described it—Owen and Sassoon, for example—did not fare so well, either during or after the war. It is alongside them that I would put the best war-poets of today: such poets as Lewis and Keyes. And though they may not be widely quoted—whatever that is worth (and it may be remembered that Housman is easier to quote than Milton)—their success with the general public is a hopeful sign that people are able to 'take' a little more in the way of honesty than they used to be. It is worth while adding that Lewis's Raiders' Dawn sold well, even before Lewis's death. But neither of them has had the freakish success of Rupert Brooke or Julian Grenfell; nor would they have hoped for it.

Mr. Grigson is right in assuming that I have not read Mr. Auden's new book, which has not yet been published over here. No one could look forward to it with more eagerness than I do: I hope it is as good as Mr. Grigson says; if it is, it will survive Mr. Grigson's praise.

BletchleyHenry Reed

|

1541. Trewin, J.C., "Old Master." Listener 53, no. 1368 (19 May 1955), 905-906.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's radio drama, Vincenzo.

|

[The following is a response to two articles written by Henry Reed, " Poetry in War Time: I—The Older Poets," and " Poetry in War Time: II—The Younger Poets," which appeared in The Listener in January, 1945. This letter to the editor, by George Richards, is mentioned in Spirit Above Wars, by Dr. Amitava Banerjee.]

The Listener, 1 February, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 838 (p. 129) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

Mr. Grigson challenges Mr. Henry Reed's ideas about war-time poetry because he does not find his own pet Auden anointed pope among contemporary poets by Mr. Reed in his first article. With your permission I would like to challenge 'Poetry in War Time' in a much more fundamental way. In the last war we had young poets writing, notably Rupert Brooke, quotations from whose poems were on everybody's lips. To have gained fame then as a poet was to be a national symbol. Now I would like to ask, in a purely scientific-objective spirit, whether there is a single four-line sequence (leave alone an entire short poem) to the credit of any of these poets mentioned by Mr. Reed which has in the same way struck the popular imagination and become common property, as did, say, several of the poems of Rupert Brooke on publication? In other words, can either Mr. Reed or Mr. Grigson quote anything written by any of the poets here complimented on their gifts which has won renown outside the literary periodicals?

I am neither so foolish as to lay it down absolutely that public (mis)quotation is a test of poetic merit nor sufficiently arrogant to assert, in the light of the results of such a test, that Mr. Reed's poets have no merit and that therefore the titles of his articles should have been 'Rubbish in War Time'. But what I do assert unhesitatingly is that if we admit that people, however they may respect contemporary poets, do not quote them, then what Mr. Reed means by poetry and what it means to the homine moyen esthétique [aesthetic of the common man] are two entirely different and distinct things. Counting myself among the latter, the more present-day poetry and poetic criticism I read the more I realise that I only deluded myself in ever thinking I understood or appreciated poetry. What I got was merely the potent but cheap thrill at the sound of mysterious but unobscure words.

PooleGeorge Richards

|

1540. Trewin. J.C., "Keeping It Up." Listener 52, no. 1342 (18 November 1954), 877. 879.

Trewin's review of Henry Reed's operatic parody, Emily Butter.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|