In 1960, Penguin Books challenged a new obscenity law in Britain, finally publishing an unexpurgated edition. According to the Obscene Publications Act of 1959, a published work would not be considered obscene if it could be shown to have literary merit. On November 2, 1960, after a six-day trial (photos), a jury declared that Lady Chatterley's Lover was not obscence, Penguin was acquitted, and the book released, selling out all 200,000 copies on the first day.

Henry Reed reviewed the newly-published edition for the Listener's Book Chronicle on November 24, 1960 (p. 948):

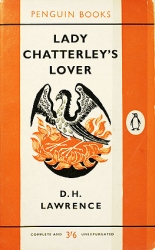

Lady Chatterley's Lover

By D.H. Lawrence. Penguin. 3s. 6d.

An atmosphere of hysterical over-excitement is not one in which a book may be most profitably read—still less reviewed. I wonder how many people have in recent weeks read the pages of Lady Chatterley's Lover consecutively, starting at page 5 and ending at page 317? We have all, like the jury at the Old Bailey, been conjured rather to dip into it here and there. This is not what Lawrence wanted at all. He wanted us to read his story, which he meant to be a good one. I have read it twice recently, and straight through. It seemed to me richer and more moving the second time than the first; but my total impression seemed on both occasions the same. Here was the mature work of a great artist, a novel which for all its occasional lightness was seriously intended to touch the heart, which had been composed with great thoroughness, and which was, like most of Lawrence's more extended works, grounded in moral protest. If I had to say what that protest consisted of, I would say that in simplest terms it is the championship of good sexual relations against bad ones: warm-hearted sexuality against cynical and cold-hearted self-indulgence and exploitation. Asked to say as briefly as possible what happens in the book, I would say that it charts the progress of its two chief characters from the desolation and forlornness in which we find them—and to which they have been reduced by present and past adversity—towards a state which holds out a promise of hard-won happiness. I cannot put it otherwise.

Others, apparently, can. We are told in a letter to The Listener of November 17 that 'as several critics have been quick to point out, Mellors already had a wife, and Lady Chatterley seems to have had no compunction about breaking up that marriage, so long as she satisfied her own lusts (she wasn't chaste even before she married Chatterley), while she apparently had no pity for her unfortunate crippled husband. And Lawrence shows no interest in what have been the fate of any illegitimate children that might have been born'. This is all wrong: in fact, in implication, and in deduction. Mellors has been long parted from his wife, beyond possibility of reconciliation; when Connie meets him he is living in contemptuous chastity, and there is no question of her breaking up a relationship. To speak of her as satisfying her own 'lusts' (surely the simple singular would be pejorative enough?) seems to me to suggest that she is merely using Mellors as an instrument, or that she is suffering from temporary or permanent nymphomania. Neither is the case. Of 'pity for her unfortunate crippled husband', she has an abundance; she also has love for him. It is he who has no pity or love for her. This is the point from which the entire plot develops. 'The fate of any illegitimate children that might have been born' is said to evoke no interest from Lawrence. But is not this the chief element in the whole last third of the book? As for Connie's 'unchastity' before marriage, this is presented by Lawrence (with mocking approval) as mechanically characteristic of her class and upbringing; and indeed the sexual side of her solitary little teen-age affair is undertaken rather as a boring fashionable duty than anything else. It is not the onset of a sexual mania.

But that people can, at either first or second hand, get such odd ideas about what characters in a book are like, and about what happens to them, is probably some sign of a book's disturbing realness. (Hardy's Tess, it may be recalled, could once be thought of as a 'little harlot'.) And Lady Chatterley's Lover is real because it is art. Lawrence's great gifts are all here: his powers of construction, of subtly unfolding a complex narrative, the sureness with which he can change his tone from sober to satirical, from bitter to pathetic, from humorous to grave; above all, his incomparable way of capturing the quickly changing shifts of feeling as the inner world of his characters is acted upon by the outer. The book is not without faults; in more extensive comments one would have to probe them. At this particular point in history one's concern must be to clear the reputation of the book from gross falsification; and to urge that all who would speak about it, either in praise or blame, should dutifully address themselves to the task of reading it, from (I repeat) page 5 to 317.Henry Reed