Then, in this last paragraph of the column for January 24th, 1948, there appears a paramount of name-dropping, blandishment, and cleverly phrased self-congratulation:

Second Opinion, discreetly and amiably presented by Mr. Frank Birch, has made an excellent and entertaining beginning. The proceedings opened with a postcard from Mr. Bernard Shaw about a discussion of Paradise Lost in which I had myself been privileged to take part. Modesty restrains me from divulging on whose side Mr. Shaw seemed to have been; what genuinely moved me was the thought that one's own humble mumblings had reached those ears at all. I have felt no comparable emotion since I gave up prayer.

[p. 70]

Between October and December of 1947, the BBC's Third Programme broadcast an eleven-part dramatization of Paradise Lost, produced by Douglas Cleverdon, who cast Dylan Thomas in the role of Lucifer. The program was not well-received, and reviewing it for his December 6th "Radio Notes" (.pdf), Reed was forced to invent the term "inauscultable" to adequately describe his disappointment:

New arts demand new words, and in its short day the radio has given us many, not always beautiful. Seeking during the last few weeks to compound a necessary word that should be at once inoffensive in sound, clear in meaning and traditional in formation, I have met with a philological difficulty. The transitive Latin verb auscultme, to listen to, hearken to, give ear to, produces in English the two verbs 'to auscult' (rare) and 'to auscultate,' the latter being familiar in medicine. Normally I would not wish to have truck with such words; the wireless I would either listen to, or switch off. It was some such word as inauscultable or inauscultatable that I wanted. After careful consideration of the rival claims of medicine and radio, I venture to suggest that inauscultatable be reserved for those organs inaudible even to the stethoscope, and that inauscultable be dedicated to such radio-programmes as Paradise Lost, which has now been going on for seven weeks, and has been more or less unlistenable-to from the very start.

[p. 449]

Thomas's performance was a particular sore spot: "Week after week," Reed says, "we have had the voice of Dylan Thomas coming up like thunder on the road to Mandalay; rarely can such gusty intakes of breath have passed across the ether."

The new series which received a postcard from George Bernard Shaw, Second Opinion, was a show of audio letters-to-the-editor, consisting of correspondence from listeners concerning the Third Programme's talk and discussion programming. Following shortly after the final chapter, Reed participated in "An Argument on 'Paradise Lost'," broadcast Sunday evening, January 4th, 1948, which must have been something of an airing of grievances. It sounds as if Reed found, in Shaw's response to the conversation, more than ample vindication for his negative review. You can almost hear him patting himself on the back! I wonder where that postcard is, today. Buried deep in the BBC Archive?

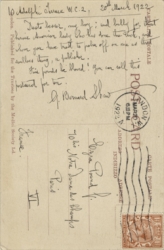

Curiously, the humble postcard seems to have been one of Shaw's preferred methods of communication (Brown University Library exhibit), and he even had personalized cards printed, some with statements of his frequently requested views on such subjects as capital punishment, vegetarianism, and his failure to garner support for a new, 42-character, British alphabet (bottom of this page). Here's a postcard from Shaw to Ezra Pound in 1922, concerning the publication of Joyce's Ulysses (at Indiana University's Lilly Library):